Turing's Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edsger Dijkstra: the Man Who Carried Computer Science on His Shoulders

INFERENCE / Vol. 5, No. 3 Edsger Dijkstra The Man Who Carried Computer Science on His Shoulders Krzysztof Apt s it turned out, the train I had taken from dsger dijkstra was born in Rotterdam in 1930. Nijmegen to Eindhoven arrived late. To make He described his father, at one time the president matters worse, I was then unable to find the right of the Dutch Chemical Society, as “an excellent Aoffice in the university building. When I eventually arrived Echemist,” and his mother as “a brilliant mathematician for my appointment, I was more than half an hour behind who had no job.”1 In 1948, Dijkstra achieved remarkable schedule. The professor completely ignored my profuse results when he completed secondary school at the famous apologies and proceeded to take a full hour for the meet- Erasmiaans Gymnasium in Rotterdam. His school diploma ing. It was the first time I met Edsger Wybe Dijkstra. shows that he earned the highest possible grade in no less At the time of our meeting in 1975, Dijkstra was 45 than six out of thirteen subjects. He then enrolled at the years old. The most prestigious award in computer sci- University of Leiden to study physics. ence, the ACM Turing Award, had been conferred on In September 1951, Dijkstra’s father suggested he attend him three years earlier. Almost twenty years his junior, I a three-week course on programming in Cambridge. It knew very little about the field—I had only learned what turned out to be an idea with far-reaching consequences. a flowchart was a couple of weeks earlier. -

The Turing Approach Vs. Lovelace Approach

Connecting the Humanities and the Sciences: Part 2. Two Schools of Thought: The Turing Approach vs. The Lovelace Approach* Walter Isaacson, The Jefferson Lecture, National Endowment for the Humanities, May 12, 2014 That brings us to another historical figure, not nearly as famous, but perhaps she should be: Ada Byron, the Countess of Lovelace, often credited with being, in the 1840s, the first computer programmer. The only legitimate child of the poet Lord Byron, Ada inherited her father’s romantic spirit, a trait that her mother tried to temper by having her tutored in math, as if it were an antidote to poetic imagination. When Ada, at age five, showed a preference for geography, Lady Byron ordered that the subject be replaced by additional arithmetic lessons, and her governess soon proudly reported, “she adds up sums of five or six rows of figures with accuracy.” Despite these efforts, Ada developed some of her father’s propensities. She had an affair as a young teenager with one of her tutors, and when they were caught and the tutor banished, Ada tried to run away from home to be with him. She was a romantic as well as a rationalist. The resulting combination produced in Ada a love for what she took to calling “poetical science,” which linked her rebellious imagination to an enchantment with numbers. For many people, including her father, the rarefied sensibilities of the Romantic Era clashed with the technological excitement of the Industrial Revolution. Lord Byron was a Luddite. Seriously. In his maiden and only speech to the House of Lords, he defended the followers of Nedd Ludd who were rampaging against mechanical weaving machines that were putting artisans out of work. -

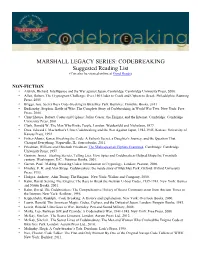

CODEBREAKING Suggested Reading List (Can Also Be Viewed Online at Good Reads)

MARSHALL LEGACY SERIES: CODEBREAKING Suggested Reading List (Can also be viewed online at Good Reads) NON-FICTION • Aldrich, Richard. Intelligence and the War against Japan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000. • Allen, Robert. The Cryptogram Challenge: Over 150 Codes to Crack and Ciphers to Break. Philadelphia: Running Press, 2005 • Briggs, Asa. Secret Days Code-breaking in Bletchley Park. Barnsley: Frontline Books, 2011 • Budiansky, Stephen. Battle of Wits: The Complete Story of Codebreaking in World War Two. New York: Free Press, 2000. • Churchhouse, Robert. Codes and Ciphers: Julius Caesar, the Enigma, and the Internet. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001. • Clark, Ronald W. The Man Who Broke Purple. London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1977. • Drea, Edward J. MacArthur's Ultra: Codebreaking and the War Against Japan, 1942-1945. Kansas: University of Kansas Press, 1992. • Fisher-Alaniz, Karen. Breaking the Code: A Father's Secret, a Daughter's Journey, and the Question That Changed Everything. Naperville, IL: Sourcebooks, 2011. • Friedman, William and Elizebeth Friedman. The Shakespearian Ciphers Examined. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1957. • Gannon, James. Stealing Secrets, Telling Lies: How Spies and Codebreakers Helped Shape the Twentieth century. Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, 2001. • Garrett, Paul. Making, Breaking Codes: Introduction to Cryptology. London: Pearson, 2000. • Hinsley, F. H. and Alan Stripp. Codebreakers: the inside story of Bletchley Park. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993. • Hodges, Andrew. Alan Turing: The Enigma. New York: Walker and Company, 2000. • Kahn, David. Seizing The Enigma: The Race to Break the German U-boat Codes, 1939-1943. New York: Barnes and Noble Books, 2001. • Kahn, David. The Codebreakers: The Comprehensive History of Secret Communication from Ancient Times to the Internet. -

An Early Program Proof by Alan Turing F

An Early Program Proof by Alan Turing F. L. MORRIS AND C. B. JONES The paper reproduces, with typographical corrections and comments, a 7 949 paper by Alan Turing that foreshadows much subsequent work in program proving. Categories and Subject Descriptors: 0.2.4 [Software Engineeringj- correctness proofs; F.3.1 [Logics and Meanings of Programs]-assertions; K.2 [History of Computing]-software General Terms: Verification Additional Key Words and Phrases: A. M. Turing Introduction The standard references for work on program proofs b) have been omitted in the commentary, and ten attribute the early statement of direction to John other identifiers are written incorrectly. It would ap- McCarthy (e.g., McCarthy 1963); the first workable pear to be worth correcting these errors and com- methods to Peter Naur (1966) and Robert Floyd menting on the proof from the viewpoint of subse- (1967); and the provision of more formal systems to quent work on program proofs. C. A. R. Hoare (1969) and Edsger Dijkstra (1976). The Turing delivered this paper in June 1949, at the early papers of some of the computing pioneers, how- inaugural conference of the EDSAC, the computer at ever, show an awareness of the need for proofs of Cambridge University built under the direction of program correctness and even present workable meth- Maurice V. Wilkes. Turing had been writing programs ods (e.g., Goldstine and von Neumann 1947; Turing for an electronic computer since the end of 1945-at 1949). first for the proposed ACE, the computer project at the The 1949 paper by Alan M. -

Global Properties of the Turing Degrees and the Turing Jump

Global Properties of the Turing Degrees and the Turing Jump Theodore A. Slaman¤ Department of Mathematics University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720-3840, USA [email protected] Abstract We present a summary of the lectures delivered to the Institute for Mathematical Sci- ences, Singapore, during the 2005 Summer School in Mathematical Logic. The lectures covered topics on the global structure of the Turing degrees D, the countability of its automorphism group, and the definability of the Turing jump within D. 1 Introduction This note summarizes the tutorial delivered to the Institute for Mathematical Sciences, Singapore, during the 2005 Summer School in Mathematical Logic on the structure of the Turing degrees. The tutorial gave a survey on the global structure of the Turing degrees D, the countability of its automorphism group, and the definability of the Turing jump within D. There is a glaring open problem in this area: Is there a nontrivial automorphism of the Turing degrees? Though such an automorphism was announced in Cooper (1999), the construction given in that paper is yet to be independently verified. In this pa- per, we regard the problem as not yet solved. The Slaman-Woodin Bi-interpretability Conjecture 5.10, which still seems plausible, is that there is no such automorphism. Interestingly, we can assemble a considerable amount of information about Aut(D), the automorphism group of D, without knowing whether it is trivial. For example, we can prove that it is countable and every element is arithmetically definable. Further, restrictions on Aut(D) lead us to interesting conclusions concerning definability in D. -

Turing's Influence on Programming — Book Extract from “The Dawn of Software Engineering: from Turing to Dijkstra”

Turing's Influence on Programming | Book extract from \The Dawn of Software Engineering: from Turing to Dijkstra" Edgar G. Daylight∗ Eindhoven University of Technology, The Netherlands [email protected] Abstract Turing's involvement with computer building was popularized in the 1970s and later. Most notable are the books by Brian Randell (1973), Andrew Hodges (1983), and Martin Davis (2000). A central question is whether John von Neumann was influenced by Turing's 1936 paper when he helped build the EDVAC machine, even though he never cited Turing's work. This question remains unsettled up till this day. As remarked by Charles Petzold, one standard history barely mentions Turing, while the other, written by a logician, makes Turing a key player. Contrast these observations then with the fact that Turing's 1936 paper was cited and heavily discussed in 1959 among computer programmers. In 1966, the first Turing award was given to a programmer, not a computer builder, as were several subsequent Turing awards. An historical investigation of Turing's influence on computing, presented here, shows that Turing's 1936 notion of universality became increasingly relevant among programmers during the 1950s. The central thesis of this paper states that Turing's in- fluence was felt more in programming after his death than in computer building during the 1940s. 1 Introduction Many people today are led to believe that Turing is the father of the computer, the father of our digital society, as also the following praise for Martin Davis's bestseller The Universal Computer: The Road from Leibniz to Turing1 suggests: At last, a book about the origin of the computer that goes to the heart of the story: the human struggle for logic and truth. -

Alan Turing, Marshall Hall, and the Alignment of WW2 Japanese Naval Intercepts

Alan Turing, Marshall Hall, and the Alignment of WW2 Japanese Naval Intercepts Peter W. Donovan arshall Hall Jr. (1910–1990) is de- The statistician Edward Simpson led the JN-25 servedly well remembered for his team (“party”) at Bletchley Park from 1943 to 1945. role in constructing the simple group His now declassified general history [12] of this of order 604800 = 27 × 33 × 52 × 7 activity noted that, in November 1943: Mas well as numerous advances in [CDR Howard Engstrom, U.S.N.] gave us combinatorics. A brief autobiography is on pages the first news we had heard of a method 367–374 of Duran, Askey, and Merzbach [5]. Hall of testing the correctness of the relative notes that Howard Engstrom (1902–1962) gave setting of two messages using only the him much help with his Ph.D. thesis at Yale in property of divisibility by three of the code 1934–1936 and later urged him to work in Naval In- groups [5-groups is the usage of this paper]. telligence (actually in the foreign communications The method was known as Hall’s weights unit Op-20-G). and was a useful insurance policy just in I was in a research division and got to see case JN-25 ever became more difficult. He work in all areas, from the Japanese codes promised to send us a write-up of it. to the German Enigma machine which Alan The JN-25 series of ciphers, used by the Japanese Turing had begun to attack in England. I Navy (I.J.N.) from 1939 to 1945, was the most made significant results on both of these important source of communications intelligence areas. -

Alan Turing's Forgotten Ideas

Alan Turing, at age 35, about the time he wrote “Intelligent Machinery” Copyright 1998 Scientific American, Inc. lan Mathison Turing conceived of the modern computer in 1935. Today all digital comput- Aers are, in essence, “Turing machines.” The British mathematician also pioneered the field of artificial intelligence, or AI, proposing the famous and widely debated Turing test as a way of determin- ing whether a suitably programmed computer can think. During World War II, Turing was instrumental in breaking the German Enigma code in part of a top-secret British operation that historians say short- ened the war in Europe by two years. When he died Alan Turing's at the age of 41, Turing was doing the earliest work on what would now be called artificial life, simulat- ing the chemistry of biological growth. Throughout his remarkable career, Turing had no great interest in publicizing his ideas. Consequently, Forgotten important aspects of his work have been neglected or forgotten over the years. In particular, few people— even those knowledgeable about computer science— are familiar with Turing’s fascinating anticipation of connectionism, or neuronlike computing. Also ne- Ideas glected are his groundbreaking theoretical concepts in the exciting area of “hypercomputation.” Accord- ing to some experts, hypercomputers might one day in solve problems heretofore deemed intractable. Computer Science The Turing Connection igital computers are superb number crunchers. DAsk them to predict a rocket’s trajectory or calcu- late the financial figures for a large multinational cor- poration, and they can churn out the answers in sec- Well known for the machine, onds. -

Charles Babbage (1791-1871)

History of Computer abacus invented in ancient China Blaise Pascal (1623-1662) ! Blaise Pascal was a French mathematician Pascal’s calculators ran with gears and wheels Pascal Calculator Charles Babbage (1791-1871) Charles Babbage was an English mathematician. Considered a “father of the computer” He invented computers but failed to build them. The first complete Babbage Engine was completed in London in 2002, 153 years after it was designed. Babbage Engine Alan Turing (1912-1954) Alan Turing was a British computer scientist. ! He proposed the concepts of "algorithm" and "computation" with the Turing machine in 1936 , which can be considered a model of a general purpose computer. Alan Turing (1912-1954) During the second World War, Turing worked for Britain’s code breaking centre. He devised a number of techniques for breaking German ciphers. Turing was prosecuted in 1952 for homosexual acts. He accepted treatment with estrogen injections (chemical castration) as an alternative to prison. Grace Hopper (1906–1992) Grace Hopper was an American computer scientist and United ! States Navy rear admiral. She created a compiler system that translated mathematical code into machine language. Later, the compiler became the forerunner to modern programming languages Grace Hopper (1906–1992) In 1947, Hopper and her assistants were working on the "granddaddy" of modern computers, the Harvard Mark II. "Things were going badly; there was something wrong in one of the circuits of the long glass- enclosed computer," she said. Finally, someone located the trouble spot and, using ordinary The bug is so famous, tweezers, removed the problem, a you can actually see two- inch moth. -

Algorithms, Turing Machines and Algorithmic Undecidability

U.U.D.M. Project Report 2021:7 Algorithms, Turing machines and algorithmic undecidability Agnes Davidsdottir Examensarbete i matematik, 15 hp Handledare: Vera Koponen Examinator: Martin Herschend April 2021 Department of Mathematics Uppsala University Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Algorithms . .1 1.2 Formalisation of the concept of algorithms . .1 2 Turing machines 3 2.1 Coding of machines . .4 2.2 Unbounded and bounded machines . .6 2.3 Binary sequences representing real numbers . .6 2.4 Examples of Turing machines . .7 3 Undecidability 9 i 1 Introduction This paper is about Alan Turing's paper On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem, which was published in 1936. In his paper, he introduced what later has been called Turing machines as well as a few examples of undecidable problems. A few of these will be brought up here along with Turing's arguments in the proofs but using a more modern terminology. To begin with, there will be some background on the history of why this breakthrough happened at that given time. 1.1 Algorithms The concept of an algorithm has always existed within the world of mathematics. It refers to a process meant to solve a problem in a certain number of steps. It is often repetitive, with only a few rules to follow. In more recent years, the term also has been used to refer to the rules a computer follows to operate in a certain way. Thereby, an algorithm can be used in a plethora of circumstances. The word might describe anything from the process of solving a Rubik's cube to how search engines like Google work [4]. -

Annals of Pure and Applied Logic Extending and Interpreting

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Annals of Pure and Applied Logic 161 (2010) 775–788 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Annals of Pure and Applied Logic journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/apal Extending and interpreting Post's programmeI S. Barry Cooper Department of Pure Mathematics, University of Leeds, Leeds LS2 9JT, UK article info a b s t r a c t Article history: Computability theory concerns information with a causal – typically algorithmic – Available online 3 July 2009 structure. As such, it provides a schematic analysis of many naturally occurring situations. Emil Post was the first to focus on the close relationship between information, coded as MSC: real numbers, and its algorithmic infrastructure. Having characterised the close connection 03-02 between the quantifier type of a real and the Turing jump operation, he looked for more 03A05 03D25 subtle ways in which information entails a particular causal context. Specifically, he wanted 03D80 to find simple relations on reals which produced richness of local computability-theoretic structure. To this extent, he was not just interested in causal structure as an abstraction, Keywords: but in the way in which this structure emerges in natural contexts. Post's programme was Computability the genesis of a more far reaching research project. Post's programme In this article we will firstly review the history of Post's programme, and look at two Ershov hierarchy Randomness interesting developments of Post's approach. The first of these developments concerns Turing invariance the extension of the core programme, initially restricted to the Turing structure of the computably enumerable sets of natural numbers, to the Ershov hierarchy of sets. -

THERE IS NO DEGREE INVARIANT HALF-JUMP a Striking

PROCEEDINGS OF THE AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY Volume 125, Number 10, October 1997, Pages 3033{3037 S 0002-9939(97)03915-4 THERE IS NO DEGREE INVARIANT HALF-JUMP RODNEY G. DOWNEY AND RICHARD A. SHORE (Communicated by Andreas R. Blass) Abstract. We prove that there is no degree invariant solution to Post's prob- lem that always gives an intermediate degree. In fact, assuming definable de- terminacy, if W is any definable operator on degrees such that a <W (a) < a0 on a cone then W is low2 or high2 on a cone of degrees, i.e., there is a degree c such that W (a)00 = a for every a c or W (a)00 = a for every a c. 00 ≥ 000 ≥ A striking phenomenon in the early days of computability theory was that every decision problem for axiomatizable theories turned out to be either decidable or of the same Turing degree as the halting problem (00,thecomplete computably enumerable set). Perhaps the most influential problem in computability theory over the past fifty years has been Post’s problem [10] of finding an exception to this rule, i.e. a noncomputable incomplete computably enumerable degree. The problem has been solved many times in various settings and disguises but the so- lutions always involve specific constructions of strange sets, usually by the priority method that was first developed (Friedberg [2] and Muchnik [9]) to solve this prob- lem. No natural decision problems or sets of any kind have been found that are neither computable nor complete. The question then becomes how to define what characterizes the natural computably enumerable degrees and show that none of them can supply a solution to Post’s problem.