Productivity Analysis and Growth of UK Financial Intermediaries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

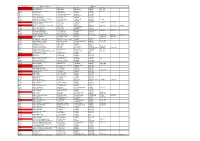

Reference Banks / Finance Address

Reference Banks / Finance Address B/F2 Abbey National Plc Abbey House Baker Street LONDON NW1 6XL B/F262 Abbey National Plc Abbey House Baker Street LONDON NW1 6XL B/F57 Abbey National Treasury Services Abbey House Baker Street LONDON NW1 6XL B/F168 ABN Amro Bank 199 Bishopsgate LONDON EC2M 3TY B/F331 ABSA Bank Ltd 52/54 Gracechurch Street LONDON EC3V 0EH B/F175 Adam & Company Plc 22 Charlotte Square EDINBURGH EH2 4DF B/F313 Adam & Company Plc 42 Pall Mall LONDON SW1Y 5JG B/F263 Afghan National Credit & Finance Ltd New Roman House 10 East Road LONDON N1 6AD B/F180 African Continental Bank Plc 24/28 Moorgate LONDON EC2R 6DJ B/F289 Agricultural Mortgage Corporation (AMC) AMC House Chantry Street ANDOVER Hampshire SP10 1DE B/F147 AIB Capital Markets Plc 12 Old Jewry LONDON EC2 B/F290 Alliance & Leicester Commercial Lending Girobank Bootle Centre Bridal Road BOOTLE Merseyside GIR 0AA B/F67 Alliance & Leicester Plc Carlton Park NARBOROUGH LE9 5XX B/F264 Alliance & Leicester plc 49 Park Lane LONDON W1Y 4EQ B/F110 Alliance Trust Savings Ltd PO Box 164 Meadow House 64 Reform Street DUNDEE DD1 9YP B/F32 Allied Bank of Pakistan Ltd 62-63 Mark Lane LONDON EC3R 7NE B/F134 Allied Bank Philippines (UK) plc 114 Rochester Row LONDON SW1P B/F291 Allied Irish Bank Plc Commercial Banking Bankcentre Belmont Road UXBRIDGE Middlesex UB8 1SA B/F8 Amber Homeloans Ltd 1 Providence Place SKIPTON North Yorks BD23 2HL B/F59 AMC Bank Ltd AMC House Chantry Street ANDOVER SP10 1DD B/F345 American Express Bank Ltd 60 Buckingham Palace Road LONDON SW1 W B/F84 Anglo Irish -

Geographies of Corporate Philanthropy: the Northern Rock Foundation

Marshall JN, Dawley S, Pike A, Pollard JS. Geographies of Corporate Philanthropy: The Northern Rock Foundation. Environment and Planning A 2017 Copyright: This is the authors’ accepted manuscript of an article that has been published in its final definitive form by Sage Publications, 2017 DOI link to article: https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X17746405 Date deposited: 19/12/2017 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License Newcastle University ePrints - eprint.ncl.ac.uk Geographies of Corporate Philanthropy: The Northern Rock Foundation by Neill Marshall, Stuart Dawley, Andy Pike, and Jane Pollard [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Forthcoming in Environment and Planning A http://journals.sagepub.com/home/epn Please note: Changes made as a result of publishing processes such as copy-editing, formatting and page numbers may not be reflected in this version. For the definitive version of this publication, please refer to the published source. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite this paper. Centre for Urban and Regional Development Studies, 1 Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE1 7RU. Geographies of Corporate Philanthropy: The Northern Rock Foundation Abstract The paper contributes to literature on the geographies of corporate philanthropy through a case study of the origins, growth and decline of the Northern Rock bank’s charitable foundation. Analysis reveals the complex, geographically-embedded nature of philanthropic motivations and impacts. It demonstrates that investment in home and community by philanthropists was part of a regionally- inscribed business-model of excessive risk taking that brought them considerable personal financial rewards. -

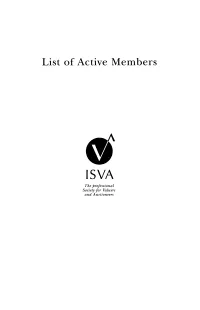

List of Active Members

List of Active Members ISVA The professional Society for Valuers and Auctioneers ACTIVE MEMBERS Abb-AIg Abbott, Dominic Charles, FRICS FSVA Adams, Richard John, FRICS FSVA Brogden &: Co, 38-39 Silver Street, Adams, Richard, 23 Warwick Row, Coventry, West Lincoln LN2 1EM Midlands CV1 lEY Tel No. 01522 531321 Tel No. 01203 251737 Elected 1975 Elected 1990 Ablitt, Ernest Henry, FSVA Adams, Roger Ian, FSVA Elected 1953 Elected 1979 Abrahams, Abi, ASVA Adamson, Gaye Elizabeth, DipVEM ASVA Elected 1994 Elected 1990 Abrahams, Peter David, FSVA Addison, Roy Matthew, DipREM ARICS ASVA Abrahams Consolidated Ltd, 51 London Road, Russell Baldwin &: Bright, (Chancellors Associates), St Albans, Hertfordshire AL11LJ 20 King Street, Hereford HR4 9DB Tel No. 01727 840111 Tel No. 01432 266663 Elected 1976 Elected 1989 Adetula, Francis Olajide Ipadeola, FSVA ARVA Abson, Stephen Paul Robert, ASVA ANAEA AlAS Elected 1995 Elected 1975 Acock, Malcolm Trevor, FSVA Aggett, Paul Anthony, ASVA Elected 1966 Ekins, 73 High Street, Burnham, Slough, Berkshire SL1 7jX Acquier, Andrew Francis, BA FSVA Tel No. 01628 604477 Andrew F Acquier, 6 Queen Street, Godalming, Elected 1981 Surrey GU7 1BD Tel No. 01483 424128 Agnew, Julian Michael, ASVA Elected 1979 Jones Lang Wootton, 22 Hanover Square, London W1A 2BN Acton, Martin Howard Harrison, ASVA Tel No. 0171 493 6040 Healey &: Baker, 29 St George Street, Hanover Elected 1988 Square, London W1A 3BG Tel No. 0171 6299292 Ahmed, Faida Yasmin, BSc ARICS ASVA Elected 1987 Elected 1995 Adams, John Alfred, FRICS FSVA Ainge, James Leonard, JP FSVA IRRV Adams Burnett, 138 Buckingham Palace Road, Elected 1973 London SW1W 9SA Tel No. -

Bradford & Bingley Transformation & Decline

Bradford & Bingley Transformation & Decline: 1995 – 2010 Matthias Hambach PhD University of York The York Management School October 2014 Abstract The recent financial and economic crisis, which affected many financial institutions in the UK, created the need to investigate and understand how the crisis affected these institutions. Consequently, numerous official reports and academic studies have been written, particularly on Northern Rock, examining the financial impact on, and business strategies of, these institutions. However, comparatively, there has been little empirical investigation into the board processes that contributed to the decisions made by the management of these affected institutions leading up to the crisis. Of particular interest to research are the demutualised building societies. They were unlike the large universal banks, who engaged heavily in investment banking and were trading on their own account; yet their organisational outcomes, in particular receipt of government support, were similar. This study focuses on the case of the former Bradford & Bingley Building Society (B&B), the last building society to demutualise, and investigates its transformation and decline over the period 1995 – 2010. The investigation adopts a novel approach by combining the Corporate Governance Life-Cycle with the Upper Echelons Perspective to examine structural and behavioural changes of the board and its governance functions, during the transition of Bradford & Bingley, from building society to bank and nationalised institution. Using a variety of sources, including interviews with directors, official documents, financial records, and newspaper articles, the transformation of B&B is examined through a historical lens. The thesis argues that life-cycle stages should not be seen as periods with well defined boundaries, but rather overlapping periods of varying length, where each period has distinct characteristics that distinguish it from another. -

Annual Report & Accounts

Annual Report & Accounts 2007 bbg.co.uk Bradford & Bingley is a UK based financial services business, focused on providing specialist mortgages and savings products. When our Company was first set up its purpose was clear: to build a better future for the people of northern mill towns. In 1851, we helped our first customer, John Abbey, build a better future for himself and his family by lending him money to buy his own home. We’re proud of our heritage. It continues to shape our business and its purpose. We’re still building a better future and we’re building it for people right across the UK. Bradford & Bingley Annual report & accounts 2007 01 Operating Contents Overview highlights 02 What we do Underlying profit before tax* £m 07 351.6 06 335.9 05 310.1 04 280.4 03 264.0 Profit before tax Directors’ report £m 04 Chairman and Chief Executive’s 07 126.0 06 246.7 introduction 05 263.5 06 Business review 04 100.2 ** 06 Our strategy 03 264.0 09 Key performance indicators 12 Our 2007 performance Underlying earnings per share* pence 18 Risk management and control 07 40.2 22 Our Board 06 38.1 05 35.4 24 Other matters 04 32.4 03 28.8 Governance Earnings per share 25 Corporate governance report pence 28 Corporate social responsibility 07 14.9 06 28.2 33 Directors’ remuneration report 05 30.1 40 Statement of Directors’ 04 4.6 responsibilities 03 32.4 Full year dividend pence 07 21.0 06 20.0 05 18.3 04 17.1 03 16.5 The accounts * A reconciliation of underlying profit before tax and the statutory measure profit 42 Independent auditor’s report before tax is provided in the summary income table on page 16. -

At Bradford & Bingley We Help You to Find the Right Home and Arrange the Right Loan, Save for Tomorrow and Invest for the Fu

BBS00030P_6ppCover 24/2/03 9:00 pm Page 1 communisisone Bradford Bradford & Bingley CONTRACT PROOF C M Y K SPOT COLOURS: BB Corporate Violet Annual Annual ReportAccounts 2002 & PMS 222 PMS ??? OTHERS: Cutter Varnish ???? CHECK CODES: _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ At Bradford & Bingley we help you to find the right _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ home and arrange the right loan, save for tomorrow _ _ _ _ and invest for the future, and protect your family and possessions – around the corner, around the country and online. Registered office: 01 Operating highlights 34 Corporate governance 47 Company balance sheet Bradford & Bingley plc 02 Business line overview 36 Directors’ remuneration 48 Consolidated cash flow Croft Road 04 Chairman’s statement report statement Crossflatts 08 Group Chief Executive’s 43 Statement of Directors’ 48 Reconciliation of movement in Bingley Annual Report & Accounts review responsibilities shareholders’ funds West Yorkshire 14 Financial review 44 Independent auditor’s report 49 Notes to the financial BD16 2UA 26 Board of Directors 45 Consolidated profit and loss statements Regisered in England No. 3938288 29 Directors’ report account 82 Shareholder information 31 Corporate social responsibility 46 Consolidated balance sheet www.bbg.co.uk Tel: 01274 555555 E: [email protected] 2002 BBS00031P_Inners 21/2/03 8:54 PM Page 1 1 Bradford & Bingley plc Annual Report & Accounts communisisone for the year ended 31 December 2002 CONTRACT PROOF C M Y K Operating highlights SPOT COLOURS: BB Corporate Violet PMS 222 PMS ??? OTHERS: Cutter Varnish ???? CHECK -

Bradford & Bingley

Offering Circular BRADFORD & BINGLEY BUILDING SOCIETY (Incorporated in England under the Building Societies Act 1986 Registered number 701B) £60,000,000 13 per cent. Permanent Interest Bearing Shares Application has been made to the Council of The International Stock Exchange of the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland Limited (the "London Stock Exchange") for the issue of £60,000,000 13 per cent. Permanent Interest Bearing Shares, comprising 6,000 PIBS of £10,000 each, (the "PIBS") of Bradford & Bingley Building Society (the "Society" or "Bradford & Bingley") to be admitted to the Official List of the London Stock Exchange. The listing of the PIBS will be expressed as a percentage of their principal amount (excluding accrued interest). It is anticipated that the PIBS will be admitted to the Official List on 4th October, 1991, subject only to the issue of the PIBS, and dealings are expected to commence on 8th October, 1991. Issue Price: 100.2 per cent. The PIBS will be deferred shares in the Society for the purposes of section 119 of the Building Societies Act 1986 and will not be protected investments for the purposes of the Building Societies Investor Protection Fund. The PIBS will not be withdrawable at the option of the PIBS holder and are repayable only in certain limited circumstances as described in "Special Terms of Issue of the PIBS—Repayment". Salomon Brothers International Limited Hoare Govett Corporate Finance Limited The date of this Offering Circular is 1st October, 1991. The Directors of the Society, whose names appear on page 12, accept responsibility for the information in this document. -

Distressed Banks, Distorted Decisions?

Distressed Banks, Distorted Decisions? Gareth Anderson*, Rebecca Riley** and Garry Young*** *University of Oxford **National Institute of Economic and Social Research, Centre For Macroeconomics, ESCoE **National Institute of Economic and Social Research, Centre For Macroeconomics EMG Workshop 2019, UNSW Disclaimer This research was carried out in part under the Bank of England's One Bank Research Agenda, but makes no use of confidential information. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors, and not necessarily those of the Bank of England or its committees. Pronounced productivity decline in the UK Motivation How do credit market imperfections contribute to aggregate productivity weakness? Banking sector weakness may reduce labour productivity: - Reduction in investment due to difficulty in accessing finance - Bond & Van Reenen (2007) Related to a sharp contraction in credit supply? - Bank forbearance (prevalence of zombie companies) - Peek & Rosengreen (2003), Caballero, Hoshi & Kashyap (2008) - Resource reallocation across companies hampered - Barlevy (2003), Haldane (2017) Background: The global financial crisis of 2008 as it played out in the UK The Different Experiences of UK Banks What we do Exploit exogenous variation induced by the financial crisis in credit availability to companies to investigate impacts of credit supply shocks Compare outcomes for companies who were subjected to tougher credit constraints to outcomes for companies that were less likely to be constrained - Quasi-experimental approach - Divide -

Bradford & Bingley

Offering Circular BRADFORD & BINGLEY BUILDING SOCIETY (Incorporated in England under the Building Societies Act 1986 Registered number 701B) £50,000,000 11 5/8 per cent. Permanent Interest Bearing Shares Application has been made to The International Stock Exchange of the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland Limited (the "London Stock Exchange") for the issue of £50,000,000 principal amount of 11 5/8 per cent. Permanent Interest Bearing Shares of £10,000 each (the "PIBS") of Bradford & Bingley Building Society (the "Society" or "Bradford & Bingley") to be admitted to the Official List. The listing of the PIBS will be expressed as a percentage of their principal amount (excluding accrued interest). It is anticipated that the PIBS will be admitted to the Official List on 17th July, 1992, subject only to the issue of the PIBS, and official dealings are expected to commence on 21st July, 1992. Issue Price: 100.129 per cent. The PIBS will be deferred shares in the Society for the purposes of section 119 of the Building Societies Act 1986 and will not be protected investments for the purposes of payments out of the Building Societies Investor Protection Fund. Attention is drawn to certain risk factors set out on page 9. The PIBS will not be withdrawable at the option of the PIBS holder and are repayable only in certain limited circumstances as described in "Special Terms of Issue of the PIBS—Repayment". Hoare Govett Corporate Finance Limited Salomon Brothers International Limited The date of this Offering Circular is 15th July, 1992. The Directors of the Society, whose names appear on page 13, accept responsibility for the information in this document. -

CAB1308 Appendix A

CAB1308 Appendix A Approved Organisations for the Investment of Council Funds Organisation Maximum Top ten Building Societies £3,000,000 Other Building Societies with assets in excess of £500 million £2,000,000 Clearing Banks with Fitch IBCA support ratings 1-3, individual £3,000,000 ratings A-B and short term credit rating F1 Wholly owned subsidiaries of the above banks £1,000,000 Other Local Authorities 3,000,000 Nationalised Industries £2,000,000 UK Government (including gilts and the Debt Management Office) £2,000,000 Instant Access Rate Accounts of the clearing banks noted above £5,000,000 Page 1 CAB1308 Appendix B Short Term Investments Outstanding as at 31st March 2006 Borrower Amount Repayment Rate £ Date % Hinckley & Rugby Building Society 1,000,000 3.4.06 5.12 Kent Reliance Building Society 1,000,000 4.4.06 5.04 Leek United Building Society 2,000,000 5.4.06 5.08 Stroud & Swindon Building Society 2,000,000 4.7.06 4.48 Cheshire Building Society 1,000,000 31.7.06 4.5 Lambeth Building Society 2,000,000 3.8.06 4.66875 Norwich and Peterborough Building Society 1,500,000 7.8.06 4.5 Cumberland Building Society 1,000,000 4.10.06 4.5 Progressive Building Society 1,000,000 5.4.06 4.51 Scarborough Building Society 1,000,000 18.4.06 4.5 Universal Building Society 1,000,000 26.10.06 4.61 Furness Building Society 1,000,000 3.11.06 4.67375 Nottingham Building Society 1,000,000 3.11.06 4.61 Nationwide Building Society 2,000,000 6.11.06 4.64 Scarborough Building Society 1,000,000 6.11.06 4.66 Bank of Scotland (Ireland) 1,000,000 9.11.06 4.66 -

Bradford & Bingley Plc Annual Report & Accounts

Bradford & Bingley plc Annual Report & Accounts for the 15 months to 31 March 2014 Registered in England and Wales under company number 03938288 Annual Report & Accounts 2014 Contents Page Strategic Report Overview 3 Business Review 3 Principal Risks and Uncertainties 7 Directors’ Report 10 Independent Auditors' Report 13 Consolidated Income Statement 16 Consolidated Statement of Comprehensive Income 17 Balance Sheets 18 Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity 19 Company Statement of Changes in Equity 20 Cash Flow Statements 21 Notes to the Financial Statements 22 Appendix A Unaudited Consolidated Income Statement 82 Unaudited Consolidated Balance Sheet 83 2 Strategic Report Annual Report & Accounts 2014 The Directors present their Annual Report and Accounts for the 15 months to 31 March 2014. Bradford & Bingley plc ('B&B' or 'the Company') is a public limited company which was incorporated in the United Kingdom under the Companies Act 2006 and is registered in England and Wales. The Company and its subsidiary undertakings comprise the Bradford & Bingley plc Group ('the Group'). Overview The Group and Company primarily operates as a servicer of mortgage loans secured on residential properties and of associated services. No new lending is carried out. On 1 October 2010 UK Asset Resolution Limited ('UKAR') was established as the holding company for B&B and NRAM plc (formerly Northern Rock (Asset Management) plc) ('NRAM'), bringing together the two brands under shared management and a common Board of Directors. After the transfer into public ownership by the Bradford & Bingley plc Transfer of Securities & Property etc. Order 2008, the Group closed its doors to new mortgage applications in 2008 and committed to lend only where a formal mortgage offer or further advance arrangement had already contractually been made. -

THE BUILDING SOCIETY PROMISE: BUILDING SOCIETIES and HOME OWNERSHIP, C.1880–1913 Luke Samy

U N I V E R S I T Y O F O X F O R D Discussion Papers in Economic and Social History Number 72, October 2008 THE BUILDING SOCIETY PROMISE: BUILDING SOCIETIES AND HOME OWNERSHIP, C.1880–1913 Luke Samy THE BUILDING SOCIETY PROMISE: BUILDING SOCIETIES AND HOME OWNERSHIP, C.1880–19131 Luke Samy Nuffield College, Oxford <[email protected]> Abstract Formed in the mid-nineteenth century, the building societies grew rapidly from their humble beginnings as localised ‘self-help’ organisations to become the dominant player in the house mortgage market by the inter-war period. Throughout the nine- teenth and early twentieth centuries, the movement presented itself as a true champion of home ownership and thrift among the working classes, but historians of housing have generally downplayed the role that building societies played, or could have played, in furthering these aims. This paper examines the archival records of two London-based building societies to investigate empirically the extent to which these institutions helped to overcome financial exclusion and to foster home ownership be- fore the First World War, a time when rental tenure was the norm. The results show that the case studies examined were not exclusively middle-class in their membership, with one of them in particular showing a genuine commitment to working-class own- er-occupation by providing loans to both skilled and unskilled workers on easy re- payment terms. Its success in doing so was based on its innovative agency network which it used to control the adverse selection and moral hazard problems involved in lending to lower-income groups.