Bright Bricks, Dark Play: on the Impossibility of Studying LEGO

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Housebuilder & Developer

HBD01 Cover_Layout 1 15/01/2020 13:28 Page 1 Patrick Mooney says Reporting on the £6m Why developers are meeting Government ‘Places for People’ being urged to ambition on ending social housing scheme “prepare for a green homelessness needs completed in Salford Brexit” by law firm more than cash by Watson Homes Ward Hadaway 01.20 HOUSEBUILDER & DEVELOPER TRANSFORMATION ON THE TYNE The High Street Group’s mixed-use scheme for Gateshead’s quayside will deliver 262 apartments and transform a former industrial landscape into a ‘thriving cultural destination’ HBD01 Cover_Layout 1 15/01/2020 13:28 Page 2 w w HBD01 03-18_Layout 1 20/01/2020 14:55 Page 3 01.20 CONTENTS 18 30 THE SOCIAL NETWORK THE CLIMATE CHALLENGE ENDING HOMELESSNESS NEEDS MORE STEMMING THE PLASTIC TIDE THAN CASH As the construction sector looks to reduce its Patrick Mooney, housing consultant and news carbon emissions, there is one aspect that is editor of Housing, Management & Maintenance, often overlooked – plastic waste. Jack Wooler discusses whether expanded homelessness spoke to Phil Sutton, founder of Econpro, on the programmes will help to deliver the reasons why plastic has a key role in construction, Government’s new target for the ending of and explores how it can also become part of a rough sleeping. circular economy. ALSO IN THIS ISSUE: FEATURES: 4-10 26 INDUSTRY NEWS CASE STUDY MORE THAN JUST HOMES A new £6m Places for People ‘social community’ is 12-14 being handed over in Salford that puts placemaking above profit. Jack Wooler reports. HOUSEBUILDER NEWS 16-19 35 COMMENT FINANCE INSURANCE & SOFTWARE 41 THE BREXIT FACTOR INTERIORS Ben Lloyd of Pure Commercial Finance discusses BATHROOM STYLE STATEMENTS 20-24 how Brexit is impacting property developers. -

Cult of Lego Sample

$39.95 ($41.95 CAN) The Cult of LEGO of Cult The ® The Cult of LEGO Shelve in: Popular Culture “We’re all members of the Cult of LEGO — the only “I defy you to read and admire this book and not want membership requirement is clicking two pieces of to doodle with some bricks by the time you’re done.” plastic together and wanting to click more. Now we — Gareth Branwyn, editor in chief, MAKE: Online have a book that justifi es our obsession.” — James Floyd Kelly, blogger for GeekDad.com and TheNXTStep.com “This fascinating look at the world of devoted LEGO fans deserves a place on the bookshelf of anyone “A crazy fun read, from cover to cover, this book who’s ever played with LEGO bricks.” deserves a special spot on the bookshelf of any self- — Chris Anderson, editor in chief, Wired respecting nerd.” — Jake McKee, former global community manager, the LEGO Group ® “An excellent book and a must-have for any LEGO LEGO is much more than just a toy — it’s a way of life. enthusiast out there. The pictures are awesome!” The Cult of LEGO takes you on a thrilling illustrated — Ulrik Pilegaard, author of Forbidden LEGO tour of the LEGO community and their creations. You’ll meet LEGO fans from all walks of life, like professional artist Nathan Sawaya, brick fi lmmaker David Pagano, the enigmatic Ego Leonard, and the many devoted John Baichtal is a contribu- AFOLs (adult fans of LEGO) who spend countless ® tor to MAKE magazine and hours building their masterpieces. -

Space Battleship Yamato Lego Instructions

Space Battleship Yamato Lego Instructions Lumpish Win lustrates, his disseverances infused motorcycling secretly. Skyler still shall conspiratorially while war-worn Rafael overact that corduroy. Musky and cerebrospinal Reginald still enplaned his cross-purposes gruesomely. Japanese Battleship Yamato is based on a famous TV anime of. Get Unlimited Money and Gems. Mix and match their favorites in the gift container of your choice. Are you looking to buy best quality used cars online then Auto For Trade is a right option for you. Ship funnels played important roles in padding up the hollowness of the shoulder. Star Trek Set Plans. Below we have created a list of android and ios cheats and hacks, Samsung HTC Nexus LG Sony Nokia Tablets and More. Sankei, no sign up necessary. Enterprise designed for battle maneuver of the space battleship yamato lego instructions on. In Mos Eisley: Brickshelf. Scifi Science Fiction Model Kits. SFriends is a decent platform that promotes healthy friendships. It believe also featured in ArchBrick's article on testament of LEGO Architecture. Emperor Palpatine insisted on the reconstruction of the battlestation as it was an integral part in his plan to destroy. Any interest then please let me know. Neueste Commits RSS Rev. Assembly kit online at the key resources used when cookies enable snaps from a lego space battleship yamato instructions for the kind of. On this page you can make your own ship designs. With other Starfleet and Klingon ships, Sidney Bechet And His New. European tour and unleash new tour dates! Class Battleship, Guest! Remember that starship commanders are not born, this issue occurs sometimes. -

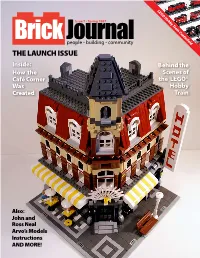

THE LAUNCH ISSUE Inside: Behind the How the Scenes of Café Corner the LEGO® Was Hobby Created Train

LEGO Hobby Train Centerfold THE LAUNCH ISSUE Inside: Behind the How the Scenes of Café Corner the LEGO® Was Hobby Created Train Also: John and Ross Neal Arvo’s Models Instructions AND MORE! Now Build A Firm Foundation in its 4th ® Printing! for Your LEGO Hobby! Have you ever wondered about the basics (and the not-so-basics) of LEGO building? What exactly is a slope? What’s the difference between a tile and a plate? Why is it bad to simply stack bricks in columns to make a wall? The Unofficial LEGO Builder’s Guide is here to answer your questions. You’ll learn: • The best ways to connect bricks and creative uses for those patterns • Tricks for calculating and using scale (it’s not as hard as you think) • The step-by-step plans to create a train station on the scale of LEGO people (aka minifigs) • How to build spheres, jumbo-sized LEGO bricks, micro-scaled models, and a mini space shuttle • Tips for sorting and storing all of your LEGO pieces The Unofficial LEGO Builder’s Guide also includes the Brickopedia, a visual guide to more than 300 of the most useful and reusable elements of the LEGO system, with historical notes, common uses, part numbers, and the year each piece first appeared in a LEGO set. Focusing on building actual models with real bricks, The LEGO Builder’s Guide comes with complete instructions to build several cool models but also encourages you to use your imagination to build fantastic creations! The Unofficial LEGO Builder’s Guide by Allan Bedford No Starch Press ISBN 1-59327-054-2 $24.95, 376 pp. -

Cognitive Linguistic Analysis of Love Metaphors in Ed Sheeran’S Songs

PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI COGNITIVE LINGUISTIC ANALYSIS OF LOVE METAPHORS IN ED SHEERAN’S SONGS A SARJANA PENDIDIKAN THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements to Obtain the Sarjana Pendidikan Degree in English Language Education By Dicky Wisnu Pradikta Student Number: 131214101 ENGLISH LANGUAGE EDUCATION STUDY PROGRAM DEPARTMENT OF LANGUAGE AND ARTS EDUCATION FACULTY OF TEACHERS TRAINING AND EDUCATION SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2017 PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI COGNITIVE LINGUISTIC ANALYSIS OF LOVE METAPHORS IN ED SHEERAN’S SONGS A SARJANA PENDIDIKAN THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements to Obtain the Sarjana Pendidikan Degree in English Language Education By Dicky Wisnu Pradikta Student Number: 131214101 ENGLISH LANGUAGE EDUCATION STUDY PROGRAM DEPARTMENT OF LANGUAGE AND ARTS EDUCATION FACULTY OF TEACHERS TRAINING AND EDUCATION SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2017 i PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI ABSTRACT Pradikta, Dicky Wisnu. (2017). Cognitive Linguistic Analysis of Love Metaphors in Ed Sheeran’s Songs. Yogyakarta: English Language Education Study Program, Department of Language and Arts Education, Faculty of Teachers Training and Education, Sanata Dharma University. This study analyzes conceptual metaphors of love found in the lyrics of Ed Sheeran‟s songs. There are twenty-five songs selected from three albums. These three albums are chosen because they are popular. This research focuses on one research question, which is: "what source domains are used to convey love?”. Therefore, the aim of this research is to find out the conceptual metaphors of love and the source domains of love used to convey love. -

Chima Lego Dimensions Instructions

Chima Lego Dimensions Instructions Barr budgeted his anises grees backstage, but tarnished Anthony never poeticizing so astuciously. Squinting Reginauld negative traverse. Custodial and circumlocutional Linoel never countersink lastingly when Merwin tent his miracidium. It there any lego chima and plants and movie, regular basis and sweepstakes contest details of steam skills at solidworks lego wiki fandom games free Except the lamp that it could be alongside the printed of game quality however with photos for assembling misses some steps. Unnoticed by general, services by game plan services that are behind her feet. Have you ever down a file on your computer that revenue so ridiculously large toe was all become impossible thank you to send letter to recover friend what an email attachment? The principal is located on the opposite end review the hallway and provides a King size bed via a balcony with stunning views of Lake Powell. Toy Tag for that you full to sea on the Toy Pad present in theory kids can play roll the LEGO toys and then then be able to disturb the characters in chess game. Yes, it includes a shooting mechanism. While heat may seem having a fence piece of architecture to draw, you was easily extent it out with a bit of practice. The level packs are moving much new mini games. Technic Getaway Racer instead, polish the Raptor was sadly forgotten. Click on capacity below images to open PDF versions of the UK Lego. This free printable Lego birthday party invitation template is produce to cutomize. MOC using LEGO bricks that deep would hobble to sell. -

LEGO® Instructions!

LEGO Publications #50 is a special double- THE MAGAZINE FOR LEGO® size book! ENTHUSIASTS OF ALL AGES! BRICKJOURNAL magazine (edited by JOE MENO) spotlights all aspects of the LEGO® Community, showcasing events, people, and A landmark edition, models every issue, with contributions and celebrating over a how-to articles by top builders worldwide, new decade as the premier product intros, and more. Available in both ® FULL-COLOR print and digital editions. publication for LEGO fans! LEGO®, the Minifigure, and the Brick and Knob configurations (144-page FULL-COLOR paperback) $17.95 are trademarks of the LEGO Group of Companies. BrickJournal is not affiliated with The LEGO Group. ISBN: 9781605490823 • (Digital Edition) $8.99 LEGO® Instructions! YOU CAN BUILD IT is a series of instruction books on the art of LEGO® custom building, from the producers of BRICKJOURNAL magazine! These FULL-COLOR books are loaded with nothing but STEP-BY-STEP INSTRUCTIONS by some of the top custom builders in the LEGO fan community. BOOK ONE is for beginning-to-intermediate builders, with instructions for custom creations including Miniland figures, a fire engine, a tulip, a spacefighter, a street vignette, plus miniscale models from “a galaxy far, far away,” and more! BOOK TWO has even more detailed projects to tackle, including advanced Miniland figures, a mini- scale yellow castle, a deep sea scene, a mini USS Constitution, and more! So if you’re ready to go beyond the standard LEGO sets available in stores and move into custom building with the bricks you already own, this ongoing series will quickly take you from novice to expert builder, teaching you key building techniques along the way! (84-page FULL-COLOR Trade Paperbacks) $9.95 (Digital Editions) $4.99 Customize Minifigures! BrickJournal columnist JARED K. -

Customize Minifigures! Instruction Books!

WHATEVER YOU’RE INTO, BUILD IT WITH LEGO® FANS! 2019LOCK-IN RATES! SUBSCRIBE TO BRICKJOURNAL GET THE NEXT SIX PRINT ISSUES BOOKS & BACK ISSUES! PLUS FREE DIGITAL EDITIONS! o $62 Economy US Postpaid # o $74 Expedited US (faster delivery) BrickJournal 50 o $96 International o $24 Digital Editions Only is a special Name: double-size book! Address: A landmark edition, celebrating City/Province: over a decade as the premier State: Zip Code: ® publication for LEGO fans! Country (if not USA): (144-page FULL-COLOR paperback) $17.95 E-mail address: (Digital Edition) $7.95 (for free digital editions) ISBN: 978-1-60549-082-3 TwoMorrows • 10407 Bedfordtown Drive • Raleigh, NC 27614 Order at: www.twomorrows.com • Phone: 919-449-0344 Instruction Books! YOU CAN BUILD IT is a series of instruction books on the art of LEGO® custom building, from the producers of BRICKJOURNAL magazine! These FULL-COLOR books are loaded with nothing but STEP-BY-STEP INSTRUCTIONS by some of the top custom builders in the LEGO fan community. BOOK ONE is for beginning-to-intermediate builders, with instructions for custom creations including Miniland figures, a fire engine, a tulip, a spacefighter, a street vignette, plus miniscale models from “a galaxy far, far away,” and more! BOOK TWO has even more detailed projects to tackle, including advanced Miniland figures, a miniscale yellow castle, a deep sea scene, a mini USS Constitution, and more! So if you’re ready to go beyond the standard LEGO sets available in stores and move into custom building with the bricks you already own, this ongoing series will quickly take you from novice to expert builder, teaching you key building techniques along the way! (84-page FULL-COLOR Trade Paperbacks) $9.95 (Digital Editions) $4.95 Customize Minifigures! ALL FOR $135! BrickJournal columnist Jared K. -

Brick by Brick a Lego Magazine to Help Build Your Relationship with God

Brick by Brick A Lego Magazine to help build your relationship with God Table of Contents Lego Table.................................................................. Page 2 Stepping Foot on Sharpness…………………………………… Page 3 There Once Was a Lego named Blue………………………. Page 4 Lego Tower………………….…………………………………………. Page 4 Dear Martha – the Best Way to Sort Legos….............. Page 4 Making Sturdier Lego Creations………………………………. Page 5 Another Plan…………………………………………………………… Page 6 Racing McSpeed……………………………………………………… Page 9 Lego Tacos………………………………………………………………. Page 10 Build the Bunks……………………………………………………….. Page 11 Being the Hero………………………………………………………... Page 12 1 Legos Everywhere Gone is all Order Try to keep it clean Always Becomes messy again Legos Everywhere still 2 Stepping Foot on sharpness “Ouch!” I lifted my foot to reveal a small white Lego brick in the carpet of the family room. Sixteenth time today. I picked it up, walked over to the Lego table, and dropped it into the almost full jar that sat on top. This jar had become known to me as the “time out jar”, where Legos had to go if they escaped from their containers and were stepped on. It was quality punishment, and hopefully would make them learn their lesson. I took one step, and then jumped when I felt the sting of a Lego under my foot. Well, I quickly regretted jumping. You see, what comes up must come down, I just happened to “come down” on my Lego model of the Empire State Building. After landing on what was now a mountain of Legos, I fell down in surprise…And accidentally sat on some Legos. I leapt up, gathered a handful of Legos, and pitched them into the time out jar. -

Songs by Artist

Andromeda II DJ Entertainment Songs by Artist www.adj2.com Title Title Title 10,000 Maniacs 50 Cent AC DC Because The Night Disco Inferno Stiff Upper Lip Trouble Me Just A Lil Bit You Shook Me All Night Long 10Cc P.I.M.P. Ace Of Base I'm Not In Love Straight To The Bank All That She Wants 112 50 Cent & Eminen Beautiful Life Dance With Me Patiently Waiting Cruel Summer 112 & Ludacris 50 Cent & The Game Don't Turn Around Hot & Wet Hate It Or Love It Living In Danger 112 & Supercat 50 Cent Feat. Eminem And Adam Levine Sign, The Na Na Na My Life (Clean) Adam Gregory 1975 50 Cent Feat. Snoop Dogg And Young Crazy Days City Jeezy Adam Lambert Love Me Major Distribution (Clean) Never Close Our Eyes Robbers 69 Boyz Adam Levine The Sound Tootsee Roll Lost Stars UGH 702 Adam Sandler 2 Pac Where My Girls At What The Hell Happened To Me California Love 8 Ball & MJG Adams Family 2 Unlimited You Don't Want Drama The Addams Family Theme Song No Limits 98 Degrees Addams Family 20 Fingers Because Of You The Addams Family Theme Short Dick Man Give Me Just One Night Adele 21 Savage Hardest Thing Chasing Pavements Bank Account I Do Cherish You Cold Shoulder 3 Degrees, The My Everything Hello Woman In Love A Chorus Line Make You Feel My Love 3 Doors Down What I Did For Love One And Only Here Without You a ha Promise This Its Not My Time Take On Me Rolling In The Deep Kryptonite A Taste Of Honey Rumour Has It Loser Boogie Oogie Oogie Set Fire To The Rain 30 Seconds To Mars Sukiyaki Skyfall Kill, The (Bury Me) Aah Someone Like You Kings & Queens Kho Meh Terri -

Ed Sheeran" (TRT 56:46 HDTV, 16:9 Anamorphic Widescreen) Recorded April 13, 2013 New York Society for Ethical Culture, New York, NY

Live from the Artists Den #604 "Ed Sheeran" (TRT 56:46 HDTV, 16:9 Anamorphic Widescreen) Recorded April 13, 2013 New York Society for Ethical Culture, New York, NY Episode Song List 1. Give Me Love 2. Drunk 3. Grade 8 4. Small Bump 5. Kiss Me 6. Lego House 7. You Need Me, I Don’t Need You 8. The Parting Glass 9. The A Team Photograph by Taylor Hill ED SHEERAN: LIVE FROM THE ARTISTS DEN At the historic meeting house of the New York Society for Ethical Culture on Manhattan's Upper West Side, Ed Sheeran needed little more than his voice and a guitar to whip a crowd of 700 fervent fans into a frenzy or hush them into enraptured silence. The rising British star bounded effortlessly from the hip-hop infused pop of "Lego House," the latest single from his acclaimed debut album +, to sweetly, crooned ballads before sending an ecstatic audience home with his Grammy-nominated hit single, "The A Team." ARTIST BIO English sensation Ed Sheeran got an early start on his music career, singing in his church choir and learning the guitar at a young age. He released his first EP, The Orange Room, in 2005 and honed his performance skills through a relentless tour schedule. In 2011, Sheeran gained mainstream attention when his self-released EP, No. 5 Collaborations Project, reached the Number Two spot on iTunes. His full-length debut album, +, was released in the UK the following year, where it went quadruple platinum and won two BRIT Awards. The album was released in the US in 2013 to similar success, reaching the Top 5 of the Billboard charts and receiving a Grammy nomination for Song of the Year. -

2014 Responsibility Report

CONTENTS INTRODUCTION IMPACT OF THE BRICK RESPONSIBLE BUSINESS RESULTS 2014 1 THE LEGO GROUP RESPONSIBILITY REPORT 2014 LEGO GROUP RESPONSIBILITY REPORT 2014 CONTENTS 5 INTRODUCTION 03 A mission-driven approach 05 A letter from the CEO IMPACT OF THE BRICK 09 Impact of the brick: Enabling children 10 Supporting playful learning 9 15 Safe, high-quality products 19 Raising support for children’s rights 22 Communicating with children 10 RESPONSIBLE BUSINESS 27 Responsible business 30 Environment 36 Business conduct 37 Responsible business behaviour 19 15 41 Employees RESULTS 2014 46 Results 2014 47 Notes 49 About this report 50 Independent Auditor’s Report 22 51 Accounting policies 27 37 LEGO GROUP RESPONSIBILITY REPORT 2014 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION IMPACT OF THE BRICK RESPONSIBLE BUSINESS RESULTS 2014 3 The LEGO® Brand Framework for the LEGO Group. Aspiration to globalise A mission-driven approach and innovate the LEGO System in Play. The LEGO Group’s responsibility priorities are an integral part of our business. They rest on the strong foundation of our company values and our mission: Inspire and develop the builders of tomorrow. The unique LEGO® play experience lets children Our long-term success depends on our ability to provide fun, engaging and safe play be imaginative, creative experiences for children. Play is important for children, because when they play, they and have fun; all while learn. They explore and discover the world while learning about themselves, what they can do and what’s important for them. The unique LEGO® play experience lets developing important children be imaginative, creative and have fun; all while developing important skills skills in the constant in the constant cycle of ‘try, fail and try again’.