Sample Chapter 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fall 2018 Catalog.Indd

fall PROGRAM OFFERINGS 2018 SEPTEMBER THROUGH DECEMBER Around the World in Fewer than 80 Days! Special Events Lecturer: David Jones Around the World in Fewer than Artifactscontents at the Georgia Capitol . 16 Monday, October 1 80 Days! . i Auguste Rodin: Refl ecting Humanity . 4 5:00pm reception; 5:30pm program; Art Gallery Opening: Fran Th omas . 22 Charles Lamar and the Slave-Trader’s 6:15pm reception continues Discovering Daufuskie Island . i Letter-Book . 4 Skidaway Island Presbyterian Church From Monet to Matisse . 16 Deadliest Catch . 20 50 Diamond Causeway Holiday Sing-Along . 23 Everyday Racism in America . 18 $15 for members; Introducing: Healthwise Fallen Empires of World War I . 5 free for visitors invited by members Movement and Stillness . 24 Fort King George . 15 Open House $25 TLC credit for members whose guests Sex and the Senior . 24 Gilded Age and Its Mansions . 2 become members on October 1 Travel Wellness . 25 Giorgio Vasari . 14 Yoga Studio . 25 Ivan Bailey This is the amazing story of Nellie Bly and Elizabeth Bisland and their & His Savannah Ironwork . 21 race against each other and Jules Verne’s fictional traveler, Phileas Fogg, to Travel King David . 14 circumnavigate the globe in fewer than 80 days in 1889-1890. Accomplished Jekyll Island: Enclave of Millionaires . 3 Managing and Curating journalists and fierce competitors, theirs is a compelling story of amazing Louisisana Sojourn . 11 a Savannah Art Gallery . 23 adventures and misadventures in the days when traveling was unpredictable, Paris to Normandy . 9 Mary Shelley and Frankenstein . 15 dangerous, and all the more challenging for single young women. -

Nellie Bly Vs. Elizabeth Bisland: the Race Around the World,” P

Vol. VI, No. 2, 2020 Surprise!! The famous Nellie Bly had a now-forgotten travel competitor. See “Nellie Bly vs. Elizabeth Bisland: The Race Around the World,” p. 2. © Corbis and © Getty Images. To be added to the Blackwell’s Almanac mailing list, email request to: [email protected] RIHS needs your support. Become a member—visit rihs.us/?page_id=4 "1 Vol. VI, No. 2, 2020 Nellie Bly vs. Elizabeth Bisland: The Race Around the World You probably know that Nellie Bly was the intrepid woman journalist Contents who went undercover into the notorious Blackwell’s Island Lunatic Asylum and later traveled around the world in a record- P 2. Nellie Bly vs. making 72 days. (See Blackwell’s Almanac, Vol. II, No. 3, 2016, at Elizabeth Bisland: The rihs.us.) What you almost certainly do not know is that Race Around the World another young lady departed the very same day in competition with her. P. 7 From the RIHS Author Matthew Goodman recounted this exciting story at February’s Archives: NY Times Ad, 1976 Roosevelt Island Historical Society library lecture. Based on his incredibly well-researched book, Eighty Days: P. 9. RI Inspires the Nellie Bly and Elizabeth Bisland’s History-Making Race Around the Visual Arts: Tom World, Goodman painted an intimate portrait of the Otterness’s “The two women who vied to outrun the 80-day ’round-the-world journey Marriage of Money and imagined by Jules Verne. Real Estate” P. 10. A Letter from the By 1889, when Bly embarked on her circumnavigation of the globe, RIHS President she had already demonstrated her utter fearlessness. -

Smithsonian.Com Nellie Bly's Record-Breaking Trip Around The

8/15/2017 Nellie Bly's Record-Breaking Trip Around the World Was, to Her Surprise, A Race | Smart News | Smithsonian Smithsonian.com SmartNews Keeping you current Nellie Bly’s Record-Breaking Trip Around the World Was, to Her Surprise, A Race In 1889, the intrepid journalist under took her voyage, mainly by steamship and train, unknowingly competing against a reporter from a rival publication 0:00 Nellie Bly in a photo dated soon after her return from her trip around the world. (CORBIS) By Marissa Fessenden smithsonian.com January 25, 2016 American journalist Nellie Bly, born Elizabeth Jane Cochran, is arguably best known today for spending ten days in a "mad-house," an early example of investigative journalism that exposed the cruelties experienced by those living in the insane asylum on New York's Blackwell's Island. Bly was a journalism pioneer, not just for women, but for all reporters. But in 1889, another one of her projects attracted even more attention: a trip around the world by train, steamship, rickshaw, horse and donkey, all accomplished in 72 days. Bly's goal was to beat the fictional Phileas Fogg's 80-day odyssey, as written in the 1873 novel by Jules Verne, but her courage and determination helped her circumnavigate the globe in just 72 days, setting a world record, besting her own goal of 75 days and—unbeknownst to her—beating out her competitor, Elizabeth Bisland of Cosmopolitan magazine. Though at the conclusion of her journey, on January 25, 1890, Bly was greeted at a New Jersey train station by a crowd of cheering supporters, her editor at Joseph Pulitzer's New York World initially resisted sending her. -

(212) 765-6900 Boston Office 545 Boylston Street

New York Office 19 West 21st Street, Suite 501, New York, NY 10010 Telephone: (212) 765-6900 Boston Office 545 Boylston Street, Suite 1100, Boston, MA 02116 Telephone: (617) 262-2400 UPCOMING MEMOIRS & BIOGRAPHIES UPCOMING MINDFULNESS/SELF-HELP STILL HERE YOU CAN’T F*CK UP YOUR KIDS BARRY SONNENFELD, CALL YOUR MOTHER THE WEDGE RUST HEART, BREATH, MIND BECOMING KIM JONG UN THE HILARIOUS WORLD OF DEPRESSION LEARNING BY HEART HI, JUST A QUICK QUESTION THIS IS BIG DON’T HAVE KIDS ROCKAWAY MIRACLE COUNTRY UPCOMING NARRATIVE NONFICTION BETSEY THE EQUIVALENTS YOU’RE NOT LISTENING AUGUST WILSON THE HUNT FOR HISTORY LAUGH LINES THE WOMEN WITH SILVER WINGS REBEL TO AMERICA THE DOCTOR WHO FOOLED THE WORLD NOTHING PERSONAL NOSTALGIA HEAD OF MOSSAD CURE-ALL GUCCI TO GOATS MADHOUSE AT THE END OF THE EARTH HOUSE OF STICKS BE WATER, MY FRIEND TOM SELLECK UNTITLED MEMOIR DANGEROUS WOMEN THE POINTER SISTERS’ FAIRYTALE BLOOD RUNS COAL SPACE IS THE PLACE STRANGERS I REGRET THAT I’M ABLE TO ATTEND CHASING THE THRILL MUHAMMED THE PROPHET THE MISSION RHAPSODY TALKING FUNNY HOW TO SAY BABYLON SQUIRREL HILL THE GLASS OF FASHION THE SECRET HISTORY OF HOME ECONOMICS THE SEEKERS INTELLIGENT LOVE KIKI MAN RAY SPRINTING THROUGH NO MAN’S LAND BLACK AND WHITE WATER AND SALT CONQUERING ALEXANDER GUN BARONS TANAQUIL SPOKEN WORD SEARCHING FOR DU BOIS OSCAR WARS FIRST TO FALL THE VORTEX UNFORGETTABLE THE GOLDEN DOOR HOW QUICKLY SHE DISAPPEARS BLOOD AND INK THE ILLNESS LESSON WE DON’T EVEN KNOW YOU ANYMORE HOW TO PRONOUNCE KNIFE ONLY THE RIVER UPCOMING SCIENCE/BUSINESS/CURRENT -

Uncovering Nellie Bly Martha Groppo

Kaleidoscope Volume 10 Article 41 August 2012 Uncovering Nellie Bly Martha Groppo Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/kaleidoscope Part of the Journalism Studies Commons, and the Women's History Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Groppo, Martha (2011) "Uncovering Nellie Bly," Kaleidoscope: Vol. 10, Article 41. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/kaleidoscope/vol10/iss1/41 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the The Office of Undergraduate Research at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kaleidoscope by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Martha Groppo—Uncovering Nellie Bly I am a rising senior history and Faculty Mentor: Dr. Ellen Furlough journalism major and a Gaines fellow. I am also a writer for the Martha Groppo’s work on Nellie Bly, Kentucky Kernel and recently a stunt journalist and social reformer finished a year as Features Edi- of the late 19th century, is a superb tor. This paper is an excerpt from analysis of a formidable and a longer historical honors thesis important woman whose historical written during the HIS 470/HIS contributions to journalism and the 471 sequence, which was taught women’s rights have largely been by Dr. Joanne Melish and Dr. neglected despite her continued name Ellen Furlough. recognition. Groppo’s work on Nellie Bly helps to fill in the gaps on Bly’s I am extremely grateful to them both for their assistance and en- historical significance as one of the first female journalists to break couragement. -

NELLIE BLY in the Sk Yy

NNEELLLLIIEE BBLLYY iinn tthhee SSkkyy Following in the footsteps of journalist Nellie Bly on the 125th anniversary of her record-breaking race around the world Rosemary J Brown FRGS "I always have a comfortable feeling that nothing is impossible if one applies a certain amount of energy in the right direction." Nellie Bly 1889 For Pauline Copyright © 2015 by Rosemary J Brown The moral right of the author has been asserted. 2 NNEELLLLIIEE BBLLYY IINN TTHHEE SSKKYY Following in the footsteps of journalist Nellie Bly on the 125th anniversary of her record-breaking race around the world Rosemary J Brown FRGS "I am absolutely amazed, and thrilled, to find out about your trip around the world, à la Nellie Bly, and to read your accounts of it in your blog. And, needless to say, to hear that Eighty Days was helpful to you in your travels. Just know how impressed I am with your travels — you’re a worthy descendant of Nellie (and Elizabeth Bisland) themselves." Matthew Goodman, author of bestseller Eighty Days: Nellie Bly and Elizabeth Bisland's History-Making Race Around the World. 3 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION: ME AND NELLIE BLY ................................................................................................... 5 Chapter I: London, England IN WHICH NELLIE RACES FROM WATERLOO TO CHARING CROSS ........................................ 6 Chapter II: Amiens, France IN WHICH NELLIE MEETS JULES VERNE ............................................................................................... 7 Chapter III: Colombo, Sri Lanka (Ceylon) IN WHICH NELLIE IS DELAYED IN CEYLON ......................................................................................... 8 Chapter IV: Singapore IN WHICH NELLIE MAKES IT HALF-WAY ROUND THE WORLD ............................................. 13 Chapter V: Hong Kong IN WHICH NELLIE EXPERIENCES PEAKS...AND TROUGHS ........................................................ 15 Chapter VI: Guangzhou (Canton), China IN WHICH NELLIE EXPLORES TEMPLES AND TIME..................................................................... -

Writers CENTER 52Nd Annual Conference Powerful Storytelling Today August 7-10, 2014 the Resort and Conference Center at Hyannis, Massachusetts

CAPE COD writers CENTER 52nd Annual Conference Powerful Storytelling Today August 7-10, 2014 The Resort and Conference Center at Hyannis, Massachusetts Fiction Nonfiction Poetry Memoir Screenwriting Authors Agents Editors Publicists Guest Speakers Publishers Online Communication Pitch Practice Faculty Reception Manuscript Evaluations Mentoring Sessions Student Readings Welcome to the 52nd Cape Cod Writers Center Conference Powerful Storytelling Today August 7-10, 2014 The Resort and Conference Center at Hyannis 34 Scudder Avenue, Hyannis, MA 02601 Storytelling is a basic human impulse that appeals to people regardless of the era, content or form of those stories. Today's publishing climate has inspired the Cape Cod Writers Center to create a summer conference which not only enhances your literary skills but shows you how to promote your print and eBooks through social media. This year, the Center has also shortened the conference to three days of workshops, classes and mentoring sessions. The long weekend dates August 7-10 enable us to better accommodate those with 9 to 5 jobs, vacation plans and other family obligations. We’ll open the conference at the lovely Resort and Conference Center of Hyannis on Thursday afternoon, August 7, with a cocktail party at 4:00 p.m., followed by faculty introductions at 6 p.m. Classes begin the next morning at 8:30 a.m. and continue through Sunday afternoon, August 10. As you look through the pages of this brochure, you’ll discover a series of intriguing one-, two- and three-day workshops. These include workshops on flash fiction, four ways to “show not tell,” an insider’s view of publishing, creating villains, blogging a successful book, changes in contemporary fiction and so much more. -

Travel and Transportation

7 TRAVEL AND TRANSPORTATION The world is a book and those who don’t travel read only a page. Augustine of Hippo Goats cross the Zojila Pass in Kashmir, India. OBJECTIVES Work with a partner. Discuss the questions. 1 Where did you go on vacation last year? talk about transportation in a city 2 Look at the picture. Would you like to drive talk about a journey here? Why/Why not? talk about a vacation 3 Which countries would you like to visit? check in and out of a hotel write a short article about a travel experience TRAVEL AND TRANSPORTATION 61 MAC_LH_AMELT_SB_L1_FPP_pp041-070.indd 61 2/22/19 2:10 PM 7.1 Getting around Talk about transportation in a city V transportation P /eɪ/ and /oʊ/ G could VOCABULARY READING Transportation A READ FOR GIST Read Where in the world are they? What A Look at the pictures in Where in the world are they? is it about? What types of transportation can you see? What other 1 buildings 2 countries 3 transportation types of transportation can you think of? B SPEAK Work in pairs. Complete the quiz. B Go to the Vocabulary Hub on page 149. C SCAN Read Six quick facts. Match facts (a–f) with pictures C SPEAK Work in pairs. Think about a time you were in a (1–6) in the quiz. different country or city. Answer the questions. D READ FOR DETAIL Read Six quick facts again. Answer 1 What types of transportation did you use? the questions. 2 Were they difficult to use? Why? 1 How old are the buses in Mumbai? 3 Were they cheap or expensive? When I was in Vietnam last year, I took a motorcycle 2 How many San Francisco trolleys are there today? taxi. -

(212) 765-6900 Boston Office 545 Boylston Street

New York Office 19 West 21st Street, Suite 501, New York, NY 10010 Telephone: (212) 765-6900 Boston Office 545 Boylston Street, Suite 1100, Boston, MA 02116 Telephone: (617) 262-2400 UPCOMING MEMOIR & BIOGRAPHY UPCOMING MINDFULNESS / SELF-HELP BARRY SONNENFELD, CALL YOUR MOTHER YOU CAN’T F*CK UP YOUR KIDS RUST THE WEDGE BECOMING KIM JONG UN HEART, BREATH, MIND LEARNING BY HEART THE HILARIOUS WORLD OF DEPRESSION THIS IS BIG HI, JUST A QUICK QUESTION BETSEY: A MEMOIR BE WATER, MY FRIEND LAUGH LINES GROWING YOUNG SPACE IS THE PLACE THE SECRETS OF SILENCE THE EQUIVALENTS TRUE AGE ROCKAWAY MIRACLE COUNTRY UPCOMING NARRATIVE NONFICTION BRIGHT PRECIOUS THING HEAD OF THE MOSSAD THE WOMEN WITH SILVER WINGS GUCCI TO GOATS THE DOCTOR WHO FOOLED THE WORLD HOW TO SAY BABYLON BLOOD RUNS COAL WHICH GOD DO YOU MEAN? SPRINTING THROUGH NO MAN’S LAND BLIND AMBITION STRANGERS RHAPSODY MADHOUSE AT THE END OF THE EARTH CRYING IN THE BATHROOM CHASING THE THRILL NOTHING PERSONAL THE MISSION DOT DOT DOT TALKING FUNNY AUGUST WILSON SQUIRREL HILL REBEL TO AMERICA PORTRAIT OF AN ARTIST UNTITLED MEMOIR BY TOM SELLECK INTELLIGENT LOVE I REGRET I AM ABLE TO ATTEND WATER AND SALT MUHAMMED THE PROPHET GUN BARONS CAN’T KNOCK THE HUSTLE THE SEEKERS CURE-ALL HORSE GIRLS NOSTALGIA KIKI MAN RAY THE SECRET HISTORY OF HOME ECONOMICS MURDER BOOK SPOKEN WORD ONBOARDING OSCAR WARS CONQUERING ALEXANDER FIRST TO FALL TANAQUIL THE VORTEX UNFORGETTABLE UPCOMING FICTION THE KINGDOM OF PREP THE GOLDEN DOOR HOW TO PRONOUNCE KNIFE BLOOD AND INK THE THIRTY NAMES OF NIGHT OTHER FRONTS ONLY -

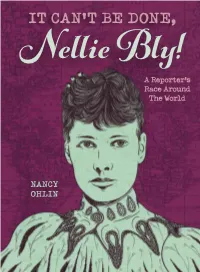

It Can't Be Done

Middle grade historical fiction OHLIN www.peachtree-online.com IT CAN’T BE DONE, Get ready to join Nellie Bly in a race against time! Nellie Bly was one of America’s first investigative reporters. Brave and outspoken, if someone A Reporter’s told her, “It can’t be done, Nellie Bly,” she went Race Around right ahead and did it anyway. After reading Jules IT CAN’T BE DONE, The World Verne’s novel, Around the World in Eighty Days, Nellie dared herself to circle the globe even faster, while reporting on her journey. Nellie was eager Nellie Bly! to face almost any obstacle–sea sickness, violent storms, and strange foods–to get her story. But an Bly! Nellie unexpected twist turned Nellie’s adventure into a high-stakes race. Shocked and worried, Nellie was still determined to win. But can it be done? “Fun, factual, and well written.” NANCY —School Library Journal OHLIN 978-1-56145-686-4 $7.99 IT CAN’T BE DONE, A Reporter’s Race Around Nellie Bly!The World For the children of Saratoga Independent School Published by PEACHTREE PUBLISHING COMPANY INC. 1700 Chattahoochee Avenue Atlanta, Georgia 30318-2112 www.peachtree-online.com Text © 2021 by Nancy Ohlin First trade paperback edition published in 2014 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Adela Pons Book design by Lily Steele Printed in January 2021 in the United States of America by Lake Book Manufacturing in Melrose Park, Illinois 10 9 8 7 6 (hardcover) 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 (trade paperback) Revised edition HC ISBN: 978-1-56145-289-7 PB ISBN: 978-1-56145-686-4 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Butcher, Nancy. -

US Foreign Correspondence in the Dawn of Trans-Atlantic Cable

Becca J. G. Godwin, Atlanta Journal-Constitution, "U.S. Foreign Correspondence in the Dawn of Trans-Atlantic Cable News: Episodic Reporting of the Killing of a French Journalist in Paris" In January 1870, U.S. newspapers and magazines--linked in direct communication with Europe since 1858 through the Trans-Atlantic telegraph cable--published timely, episodic stories out of Paris about the ramifications of the killing of a young French journalist by a cousin of Emperor Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte III. The advent of “cable news" for a dramatic and continuing saga fulfilled the vision of earlier publishers to “eradicate time.” The cable allowed readers to follow serially the many episodes in the drama, from the shooting of Victor Noir to the mass street protests against the regime, the funeral, and the murder trial. “No one speaks of anything but the death of Noir!” exclaimed the famous Parisian author of Madame Bovary, Gustave Flaubert. U.S. press reports often sympathized with Victor Noir – partly because he was a journalist -- but also because the French Emperor Napoleon III was unpopular in America. During the American Civil War, Napoleon had considered intervening on the side the Confederacy. Then, while Americans were distracted by the war, Napoleon gained a foothold on the American continent when his army conquered Mexico and he installed a European prince Maximillian as Mexico’s emperor. This paper takes a fresh look at the episodic coverage of the case of Victor Noir – a journalist who became famous because of the manner of his death – a turning point in American foreign correspondence, highlighting the increasing use of overseas cable news from Europe, both for journalistic timeliness and for public consumption. -

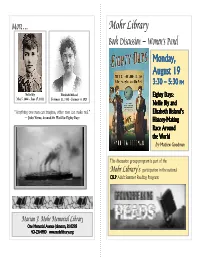

Mohr Library Book Discussion – Women's Panel More…

More … Mohr Library Book Discussion – Women’s Panel Monday, August 19 3:30 ––– 5: 5:30303030 PMPMPM Nellie Bly Elizabeth Bisland Eighty Days: May 5, 1864 – June 27, 1922 Fe bruary 11, 1 861 – January 6, 1929 Nellie Bly and Nellie Bly and “Anything one man can imagine, other men can make real.” Elizabeth BislandBisland’’’’ss ― Jules Verne, Around the World in Eighty Days HistoryHistory----MakingMaking RRRaRaaacece Around the World by Mathew Goodman This discussion group program is part of the Mohr Library’s participation in the national CSLP Adult Summer Reading Program: Marian J. M ohr Memorial Library One Memorial Avenue Johnston, RI 02919 401401----231231231231----49804980 www.mohrlibrary.org [from Random House] Book Su mmary How to par ticipate in a Discussion On November 14, 1889, Nellie Bly, the crusading young female reporter for [from Litlovers] Joseph Pulitzer’s World newspaper, left New York City by steamship on a quest to break the record for the fastest trip around the world. Also departing from New York that day—and heading in the opposite direction by train—was a young journalist from The Cosmopolitan magazine, Elizabeth Bisland. Each woman was Watch your language! Try to avoid words like "awful" or determined to outdo Jules Verne’s fictional hero Phileas Fogg and circle the globe "idiotic"—even "like" and "dislike." They don't help move discussions in less than eighty days. The dramatic race that ensued would span twenty-eight forward and can put others on the defensive. Instead, talk about your thousand miles, captivate the nation, and change both competitors’ lives forever.