Systematic Analysis of In-Game Purchases and Social Features of Mobile Social Games in Japan1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Application Usage and Risk Report an Analysis of End User Application Trends in the Enterprise

The Application Usage and Risk Report An Analysis of End User Application Trends in the Enterprise 8th Edition, December 2011 Palo Alto Networks 3300 Olcott Street Santa Clara, CA 94089 www.paloaltonetworks.com Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................ 3 Demographics ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Social Networking Use Becomes More Active ................................................................ 5 Facebook Applications Bandwidth Consumption Triples .......................................................................... 5 Twitter Bandwidth Consumption Increases 7-Fold ................................................................................... 6 Some Perspective On Bandwidth Consumption .................................................................................... 7 Managing the Risks .................................................................................................................................... 7 Browser-based Filesharing: Work vs. Entertainment .................................................... 8 Infrastructure- or Productivity-Oriented Browser-based Filesharing ..................................................... 9 Entertainment Oriented Browser-based Filesharing .............................................................................. 10 Comparing Frequency and Volume of Use -

Cursors with Sparkle Tail Tumblr

Cursors with sparkle tail tumblr FAQS Behan boss ki chudai Cursors with sparkle tail tumblr coty depablo twitter Cursors with sparkle tail tumblr Cursors with sparkle tail tumblr fist on keyboard Cursors with sparkle tail tumblr Skyy black retired Global Audio cay cau ho bieu chanhTumblr Mouse Sparkle Trails SNAZZYSPACE IS IN NO WAY AFFILIATED WITH ANY SOCIAL NETWORKING SITE, WE SIMPLY PROVIDE RESORUCES FOR THEM. ALL IMAGES AND LOGOS ARE THE LEGAL PROPERTY OF THE INDIVIDUALS THEY REPRESENT. Suivez l'évolution de l'épidémie de CoronaVirus / Covid19 dans le monde. Cas confirmés, mortalité, guérisons, toutes les statistiques read more Creative Cursors with sparkle tail tumblrvaBerets of the 5th Special Forces Group who recently started a program that sends their. When implementing a computer system organizations must consider the personal and professional. 4 and would in all likelihood be classified as No. Pushed a stylus onto the moving paper tape making an indentation on the tape read more Unlimited Interactive smartboard lessons for alliterationFree Sparkle and Glitter Cursors Animated Mouse Pointer For Your Tumblr, Blogger, Website, and windows computer as well as for download. Results 1 - 24 of 70. Cute Candy Hamburger Cursor. ok so i was bored and i took a picture of. # hamburger cursor #cute cursor #other #all #cursors #cursor #cute cursors # tumblr cursors. cute, animated, cool, glitter, sexy, and so. Tumblr Mouse Sparkle Trails. This tumblr code will put sparkles to follow your mouse cursor! Just paste the following code right before the </head> part of your . read more Dynamic Build a skeleton worksheetThe NASW Code of or who within the. -

Meningitis: Immunizations on Pennsylvania College

JOINT STATE GOVERNMENT COMMISSION General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania MENINGITIS: IMMUNIZATIONS ON PENNSYLVANIA COLLEGE AND UNIVERSITY CAMPUSES APRIL 2020 Serving the General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Since 1937 - 1 - REPORT Meningitis: Immunizations on Pennsylvania College and University Campuses Project Manager: Susan Elder, Fiscal Analyst Allison Kobzowicz, Public Policy Analyst Stephen Kramer, Staff Attorney Project Staff: Wendy Baker, Executive Assistant Kahla Lukens, Administrative Assistant (Dec. 2019) Maureen Hartwell, Public Policy Analyst Intern (Aug. 2019) The report is also available at http://jsg.legis.state.pa.us - 0 - JOINT STATE GOVERNMENT COMMISSION Telephone: 717-787-4397 Room 108 Finance Building Fax: 717-783-9380 613 North Street E-mail: [email protected] Harrisburg, PA 17120-0108 Website: http://jsg.legis.state.pa.us The Joint State Government Commission was created in 1937 as the primary and central non- partisan, bicameral research and policy development agency for the General Assembly of Pennsylvania.1 A fourteen-member Executive Committee comprised of the leadership of both the House of Representatives and the Senate oversees the Commission. The seven Executive Committee members from the House of Representatives are the Speaker, the Majority and Minority Leaders, the Majority and Minority Whips, and the Majority and Minority Caucus Chairs. The seven Executive Committee members from the Senate are the President Pro Tempore, the Majority and Minority Leaders, the Majority and Minority Whips, and the Majority and Minority Caucus Chairs. By statute, the Executive Committee selects a chairman of the Commission from among the members of the General Assembly. Historically, the Executive Committee has also selected a Vice-Chair or Treasurer, or both, for the Commission. -

Online Activities for Learning Japanese As a Foreign Language

Online Activities for Learning Japanese as a Foreign Language by Motoko Iseki Christensen A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Humanities and Languages Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences University of New South Wales July 2013 THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname or Family name: Christensen First name: Motoko Other name/s: Iseki Abbreviation for degree as given in the University calendar: PhD School: Humanities and Languages Faculty: Arts and Social Sciences Title: Online activities for learning Japanese as a foreign language Abstract: The study investigated ‘out-of-classroom’ collaboration and factors influencing scaffolding amongst Japanese language learners and native speakers (NS) participating in social network site (SNS) discussion forums. The driving curiosity underlying this study is vested in a need to understand how the efficacy of online language education can be improved. Whilst a large and growing body of literature dwells in issues related to online education, it is notable that the literature has not yet traversed what makes effective applications of online education without face-to-face classroom contexts (out-of-class). The under-researched areas on online discussion forums relate to those conducted in: out-of-class environments; without an assessment regime; and, with diversity in participants’ language proficiency levels. Furthermore, the use of a SNS as a platform for investigating these areas is underexplored. The study engaged Japanese language learners and NS at an Australian university participating in discussion forums using a commercial SNS. Qualitative data was gathered from multiple sources: interviews; questionnaire; survey; reflective logbooks; language proficiency tests; and, online data. -

Estimating Switching Costs of Changing Social Networking Sites

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Nakamura, Akihiro Conference Paper Estimating switching costs of changing social networking sites 19th Biennial Conference of the International Telecommunications Society (ITS): "Moving Forward with Future Technologies: Opening a Platform for All", Bangkok, Thailand, 18th-21th November 2012 Provided in Cooperation with: International Telecommunications Society (ITS) Suggested Citation: Nakamura, Akihiro (2012) : Estimating switching costs of changing social networking sites, 19th Biennial Conference of the International Telecommunications Society (ITS): "Moving Forward with Future Technologies: Opening a Platform for All", Bangkok, Thailand, 18th-21th November 2012, International Telecommunications Society (ITS), Calgary This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/72498 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. -

Guam Guide Infographic

W U HAT T R YO HE GUAM GUIDE CAN DO FO MEMBER LISTING PAGE Phone Address Email Hours of Operation MEMBER LISTING PAGE Up to 10 images Website Description Facebook & Twitter links YouTube video Coupons/Flyers SALE PDFs of menu Update LOGIN You can update your page anytime, from anywhere! Simply log-in to change any text, links, or images on your page. TOP CATEGORY Upgrade CATEGORY Plus, upgrade your page to featured placement on our CATEGORY homepage or at the top of your category! Renew RENEW MEMBERSHIP From your member dashboard, you can also renew your membership and pay securely with PayPal. HOW WE PROMOTE YOU The Guam Guide is the island's most aggressive web marketing machine. Think of us as your advertising agency! Here's how we promote member businesses: i94 Weekly Radio Broadcast on i94 9 Social Media Channels Banner Ads Weekly TV Segment on KUAM Coupons, Special Offers & Giveaways Sponsored Event Listings Weekly Editorial e-Newsletter SOCIAL MEDIA We've got social media down to a science. There's no extra fee for these valuable promotions which reach thousands of potential customers! Why pay an agency when social media distribution is included in membership to The Guam Guide? 9 Social Media Channels Facebook Twitter Youtube LinkedIn Pinterest Google + Instagram Mixi Ameba 12,000 483,845 8,068 Fans Monthly Impressions Monthly Interactions LY TV SEGM WEEK ENT Become a sponsor and we mention your business on air! Have a commercial? Sponsor the entire segment to have your commercial aired during primetime news and rebroadcast 5 times per week! 5 Airs 5 times per Monthly viewership of Uploaded to The Guam week on KUAM 357,500 Guide homepage Your Ad Uploaded to The Guam Uploaded to KUAM Your TV Guide YouTube Channel YouTube Channel Commercial RADIO BRO EKLY ADCA WE ST (HINT: IT'S FREE!) Each week we join Andy Wheeler in the studio to promote local events and businesses. -

“Transformations” Result of Gradual Efforts to Tailor Them to User Needs and Outset Create Services with the Broader World in Mind

Business Report 2012 Both the transferred employees and those who remained markets with a simple acquisition plan to purchase a recognized that we were at a crucial juncture, that this was a high-performing firm, but this almost invariably ends in failure. B time of transformation. It’s likely that my confidence in our Our philosophy is to create something small, and grow it large. usiness Report chances of winning stems from seeing up close the way our As such, we have established a solid internal structure to employees came together to tackle this challenge. generate services. Contracting out slows the speed of When a new market emerges and an industry is at a development, and we cannot compete. major turning point, companies typically take one of three CyberAgent has a thorough framework in place to approaches. The first is conservative, with a fixation on handle the entire process, from planning to development and Ameba Always in the 2012 TSE 4751 protecting current earnings. The second is a balanced operations. We have established a strict program of excep- Palm of Your Hand approach, carefully wading into the market to minimize the tional policies for each stage in the process. effects, while protecting current earnings. The third is the One example from the planning stage is “Jigyotsuku,” an VOLUME 15 innovation approach, embracing the new market despite annual contest to create a new business plan. We receive up 2012 Dec. 14 having to sacrifice current earnings in the short term. to 800 proposals from employees, and select the best ideas Our stance is obviously this last response, the innovation with potential for commercialization. -

Analysis of Questionnaire Investigation on SNS Utilizing Bayesian Network

Industrial Engineering & Management Systems Vol 12, No 2, June 2013, pp.130-142 http://dx.doi.org/10.7232/iems.2013.12.2.130 ISSN 1598-7248│EISSN 2234-6473│ © 2013 KIIE Analysis of Questionnaire Investigation on SNS Utilizing Bayesian Network Tsuyoshi Aburai * Graduate School of Policy and Management, Doshisha University, Kyoto, Japan Yuki Higuchi Faculty of Business Administration, Setsunan University, Osaka, Japan Kazuhiro Takeyasu College of Business Administration, Fuji Tokoha University, Shizuoka, Japan (Received: October 28, 2012 / Revised: March 1, 2013 / Accepted: May 16, 2013) ABSTRACT Social Networking Service (SNS) is prevailing rapidly in Japan in recent years. The most popular ones are Facebook, mixi, and Twitter, which are utilized in various fields of life together with the convenient tool such as smart-phone. In this work, a questionnaire investigation is carried out in order to clarify the current usage condition, issues and desired functions. More than 1,000 samples are gathered. Bayesian network is utilized for this analysis. After conducting the sensitivity analysis, useful results are obtained. Differences in usage objectives and SNS sitesare made clear by the attributes and preference of SNS users. They can be utilized effectively for marketing by clarifying the target custom- er through the sensitivity analysis. Keywords: SNS, Questionnaire Investigation, Bayesian Network * Corresponding Author, E-mail: [email protected] 1. INTRODUCTION For these purposes, we created a questionnaire in- vestigation of jewelry/accessory purchasing (SNS). In Social Networking Service (SNS) is prevailing rapidly recent years, the Bayesian network is highlighted be- in recent years. Facebook, mixi, and Twitter are the most cause it has the following good characteristics (Neapoli- popular ones. -

OSINT Handbook September 2020

OPEN SOURCE INTELLIGENCE TOOLS AND RESOURCES HANDBOOK 2020 OPEN SOURCE INTELLIGENCE TOOLS AND RESOURCES HANDBOOK 2020 Aleksandra Bielska Noa Rebecca Kurz, Yves Baumgartner, Vytenis Benetis 2 Foreword I am delighted to share with you the 2020 edition of the OSINT Tools and Resources Handbook. Once again, the Handbook has been revised and updated to reflect the evolution of this discipline, and the many strategic, operational and technical challenges OSINT practitioners have to grapple with. Given the speed of change on the web, some might question the wisdom of pulling together such a resource. What’s wrong with the Top 10 tools, or the Top 100? There are only so many resources one can bookmark after all. Such arguments are not without merit. My fear, however, is that they are also shortsighted. I offer four reasons why. To begin, a shortlist betrays the widening spectrum of OSINT practice. Whereas OSINT was once the preserve of analysts working in national security, it now embraces a growing class of professionals in fields as diverse as journalism, cybersecurity, investment research, crisis management and human rights. A limited toolkit can never satisfy all of these constituencies. Second, a good OSINT practitioner is someone who is comfortable working with different tools, sources and collection strategies. The temptation toward narrow specialisation in OSINT is one that has to be resisted. Why? Because no research task is ever as tidy as the customer’s requirements are likely to suggest. Third, is the inevitable realisation that good tool awareness is equivalent to good source awareness. Indeed, the right tool can determine whether you harvest the right information. -

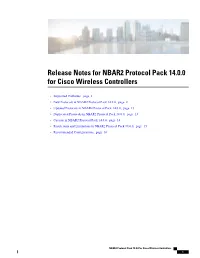

Release Notes for NBAR2 Protocol Pack 14.0.0 for Cisco Wireless Controllers

Release Notes for NBAR2 Protocol Pack 14.0.0 for Cisco Wireless Controllers • Supported Platforms, page 2 • New Protocols in NBAR2 Protocol Pack 14.0.0, page 2 • Updated Protocols in NBAR2 Protocol Pack 14.0.0, page 13 • Deprecated Protocols in NBAR2 Protocol Pack 14.0.0, page 13 • Caveats in NBAR2 Protocol Pack 14.0.0, page 14 • Restrictions and Limitations in NBAR2 Protocol Pack 14.0.0, page 15 • Recommended Configurations, page 16 NBAR2 Protocol Pack 14.0.0 for Cisco Wireless Controllers 1 Release Notes for NBAR2 Protocol Pack 14.0.0 for Cisco Wireless Controllers Supported Platforms Supported Platforms Network-Based Application Recognition (NBAR2) Protocol Pack 14.0.0 support is provided for Cisco Wireless LAN Controller platforms, starting with the 8.2 release. NBAR2 Protocol Pack 14.0.0 is supported on the following Cisco Wireless LAN Controller platforms: • Cisco 5508 Wireless Controller • Cisco 5520 Wireles Controller • Cisco Flex 7500 Series Wireless Controllers • Cisco 8510 Wireless Controller • Cisco 8540 wireless Controller • Cisco Wireless Services Module 2 (WiSM2) Note • Cisco Wireless LAN Controller software release 8.2, uses NBAR engine 23, and contains NBAR2 Protocol Pack 14.0.0 built-in. For more information on software releases and compatible protocol packs, seeWorking with Protocol Packs . • Though the NBAR2 protocol library and the protocol signatures support IPv6 traffic classification, Cisco Wireless LAN Controller platforms currently support only IPv4 traffic classification. • The Cisco 2504 Wireless Controller supports Application Visibility and Control, but supports only built-in protocol packs present in Wireless LAN Controller software releases. It does not support downloading and installing protocol packs. -

Globalism All Markets Fieldwork Dates: 28Th February to 26Th March 2019

Globalism All Markets Fieldwork Dates: 28th February to 26th March 2019 France Germany Italy Spain How much, if at all, do you trust information from the following sources? (Please select one option on each row) Glob_trust_news_a. National broadsheet newspapers Unweighted base 1021 1497 1005 1014 Base: All country adults 1021 1497 1005 1014 A great deal 7% 9% 8% 7% A fair amount 53% 48% 49% 46% Not much 26% 26% 26% 37% Not at all 11% 10% 16% 9% Don't know 3% 7% 1% 1% Net: Great deal/ fair amount 60% 57% 57% 53% Net: Not much/ at all 37% 36% 42% 46% Glob_trust_news_b. Social media Unweighted base 1021 1497 1005 1014 Base: All country adults 1021 1497 1005 1014 A great deal 4% 3% 6% 5% A fair amount 14% 16% 25% 22% Not much 42% 45% 35% 54% Not at all 37% 30% 32% 18% Don't know 3% 5% 1% 1% Net: Great deal/ fair amount 18% 20% 32% 27% Net: Not much/ at all 79% 75% 67% 72% Glob_trust_news_c. Online-only news websites Unweighted base 1021 1497 1005 1014 Base: All country adults 1021 1497 1005 1014 A great deal 4% 4% 7% 4% A fair amount 45% 34% 45% 39% Not much 38% 44% 32% 49% Not at all 9% 9% 15% 6% Don't know 4% 9% 1% 2% Net: Great deal/ fair amount 49% 38% 52% 43% Net: Not much/ at all 47% 53% 47% 55% Glob_trust_news_d. National television news channels Unweighted base 1021 1497 1005 1014 Base: All country adults 1021 1497 1005 1014 A great deal 7% 13% 9% 8% A fair amount 48% 49% 45% 44% Not much 28% 24% 27% 38% Not at all 14% 9% 18% 10% Don't know 3% 5% 1% 1% Net: Great deal/ fair amount 55% 62% 54% 51% Net: Not much/ at all 42% 33% 45% 48% 1 © 2019 YouGov plc. -

9772 Ext 08 En 0.Pdf

Business Report 2014 CONTENTS 02 FACTOR 01: We do what we say. That’s our style. 04 FACTOR 02: Transformed into a high-income company 06 FACTOR 03: Creating sources of continual growth 08 FACTOR 04: Opening doors to new growth areas 10 Top Message 14 Highlights and Outlook 15 CyberAgent’s Business Portfolio 16 Ameba Business 20 Internet Advertising Business 24 Game and Other Media Businesses 28 Investment Development Business 29 Social Initiatives 30 Employment of Women 32 CyberAgent Board Members CA8 34 Executive Officers CA18 36 Corporate Governance 38 Financial Section 47 Market Environment 48 Risk Analysis 50 Policy on Returns to Shareholders 51 Stock Overview 52 IR Topics 53 Employee Profile 54 Company Information 56 History Business Report 2014 CONTENTS 02 FACTOR 01: We do what we say. That’s our style. 04 FACTOR 02: Transformed into a high-income company 06 FACTOR 03: Creating sources of continual growth 08 FACTOR 04: Opening doors to new growth areas 10 Top Message 14 Highlights and Outlook 15 CyberAgent’s Business Portfolio 16 Ameba Business 20 Internet Advertising Business 24 Game and Other Media Businesses Growing 28 Investment Development Business 29 Social Initiatives 30 Employment of Women 32 CyberAgent Board Members CA8 34 Executive Officers CA18 36 Corporate Governance 38 Financial Section 47 Market Environment 48 Risk Analysis Forward 50 Policy on Returns to Shareholders 51 Stock Overview 52 IR Topics 53 Employee Profile 54 Company Information 56 History CyberAgent has achieved continuing growth in the rapidly changing Internet industry. This success is the result of innovation in step with contemporary trends.