Case Report Acanthamoeba Meningoencephalitis Following Autologous Peripheral Stem Cell Transplantation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Intestinal Protozoa

The Intestinal Protozoa A. Introduction 1. The Phylum Protozoa is classified into four major subdivisions according to the methods of locomotion and reproduction. a. The amoebae (Superclass Sarcodina, Class Rhizopodea move by means of pseudopodia and reproduce exclusively by asexual binary division. b. The flagellates (Superclass Mastigophora, Class Zoomasitgophorea) typically move by long, whiplike flagella and reproduce by binary fission. c. The ciliates (Subphylum Ciliophora, Class Ciliata) are propelled by rows of cilia that beat with a synchronized wavelike motion. d. The sporozoans (Subphylum Sporozoa) lack specialized organelles of motility but have a unique type of life cycle, alternating between sexual and asexual reproductive cycles (alternation of generations). e. Number of species - there are about 45,000 protozoan species; around 8000 are parasitic, and around 25 species are important to humans. 2. Diagnosis - must learn to differentiate between the harmless and the medically important. This is most often based upon the morphology of respective organisms. 3. Transmission - mostly person-to-person, via fecal-oral route; fecally contaminated food or water important (organisms remain viable for around 30 days in cool moist environment with few bacteria; other means of transmission include sexual, insects, animals (zoonoses). B. Structures 1. trophozoite - the motile vegetative stage; multiplies via binary fission; colonizes host. 2. cyst - the inactive, non-motile, infective stage; survives the environment due to the presence of a cyst wall. 3. nuclear structure - important in the identification of organisms and species differentiation. 4. diagnostic features a. size - helpful in identifying organisms; must have calibrated objectives on the microscope in order to measure accurately. -

A Revised Classification of Naked Lobose Amoebae (Amoebozoa

Protist, Vol. 162, 545–570, October 2011 http://www.elsevier.de/protis Published online date 28 July 2011 PROTIST NEWS A Revised Classification of Naked Lobose Amoebae (Amoebozoa: Lobosa) Introduction together constitute the amoebozoan subphy- lum Lobosa, which never have cilia or flagella, Molecular evidence and an associated reevaluation whereas Variosea (as here revised) together with of morphology have recently considerably revised Mycetozoa and Archamoebea are now grouped our views on relationships among the higher-level as the subphylum Conosa, whose constituent groups of amoebae. First of all, establishing the lineages either have cilia or flagella or have lost phylum Amoebozoa grouped all lobose amoe- them secondarily (Cavalier-Smith 1998, 2009). boid protists, whether naked or testate, aerobic Figure 1 is a schematic tree showing amoebozoan or anaerobic, with the Mycetozoa and Archamoe- relationships deduced from both morphology and bea (Cavalier-Smith 1998), and separated them DNA sequences. from both the heterolobosean amoebae (Page and The first attempt to construct a congruent molec- Blanton 1985), now belonging in the phylum Per- ular and morphological system of Amoebozoa by colozoa - Cavalier-Smith and Nikolaev (2008), and Cavalier-Smith et al. (2004) was limited by the the filose amoebae that belong in other phyla lack of molecular data for many amoeboid taxa, (notably Cercozoa: Bass et al. 2009a; Howe et al. which were therefore classified solely on morpho- 2011). logical evidence. Smirnov et al. (2005) suggested The phylum Amoebozoa consists of naked and another system for naked lobose amoebae only; testate lobose amoebae (e.g. Amoeba, Vannella, this left taxa with no molecular data incertae sedis, Hartmannella, Acanthamoeba, Arcella, Difflugia), which limited its utility. -

Experimental Listeria–Tetrahymena–Amoeba Food Chain Functioning Depends on Bacterial Virulence Traits Valentina I

Pushkareva et al. BMC Ecol (2019) 19:47 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12898-019-0265-5 BMC Ecology RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Experimental Listeria–Tetrahymena–Amoeba food chain functioning depends on bacterial virulence traits Valentina I. Pushkareva1, Julia I. Podlipaeva2, Andrew V. Goodkov2 and Svetlana A. Ermolaeva1,3* Abstract Background: Some pathogenic bacteria have been developing as a part of terrestrial and aquatic microbial eco- systems. Bacteria are consumed by bacteriovorous protists which are readily consumed by larger organisms. Being natural predators, protozoa are also an instrument for selection of virulence traits in bacteria. Moreover, protozoa serve as a “Trojan horse” that deliver pathogens to the human body. Here, we suggested that carnivorous amoebas feeding on smaller bacteriovorous protists might serve as “Troy” themselves when pathogens are delivered to them with their preys. A dual role might be suggested for protozoa in the development of traits required for bacterial passage along the food chain. Results: A model food chain was developed. Pathogenic bacteria L. monocytogenes or related saprophytic bacteria L. innocua constituted the base of the food chain, bacteriovorous ciliate Tetrahymena pyriformis was an intermedi- ate consumer, and carnivorous amoeba Amoeba proteus was a consumer of the highest order. The population of A. proteus demonstrated variations in behaviour depending on whether saprophytic or virulent Listeria was used to feed the intermediate consumer, T. pyriformis. Feeding of A. proteus with T. pyriformis that grazed on saprophytic bacteria caused prevalence of pseudopodia-possessing hungry amoebas. Statistically signifcant prevalence of amoebas with spherical morphology typical for fed amoebas was observed when pathogenic L. -

CH28 PROTISTS.Pptx

9/29/14 Biosc 41 Announcements 9/29 Review: History of Life v Quick review followed by lecture quiz (history & v How long ago is Earth thought to have formed? phylogeny) v What is thought to have been the first genetic material? v Lecture: Protists v Are we tetrapods? v Lab: Protozoa (animal-like protists) v Most atmospheric oxygen comes from photosynthesis v Lab exam 1 is Wed! (does not cover today’s lab) § Since many of the first organisms were photosynthetic (i.e. cyanobacteria), a LOT of excess oxygen accumulated (O2 revolution) § Some organisms adapted to use it (aerobic respiration) Review: History of Life Review: Phylogeny v Which organelles are thought to have originated as v Homology is similarity due to shared ancestry endosymbionts? v Analogy is similarity due to convergent evolution v During what event did fossils resembling modern taxa suddenly appear en masse? v A valid clade is monophyletic, meaning it consists of the ancestor taxon and all its descendants v How many mass extinctions seem to have occurred during v A paraphyletic grouping consists of an ancestral species and Earth’s history? Describe one? some, but not all, of the descendants v When is adaptive radiation likely to occur? v A polyphyletic grouping includes distantly related species but does not include their most recent common ancestor v Maximum parsimony assumes the tree requiring the fewest evolutionary events is most likely Quiz 3 (History and Phylogeny) BIOSC 041 1. How long ago is Earth thought to have formed? 2. Why might many organisms have evolved to use aerobic respiration? PROTISTS! Reference: Chapter 28 3. -

A PRELIMINARY NOTE on TETRAMITUS, a STAGE in the LIFE CYCLE of a COPROZOIC AMOEBA by MARTHA BUNTING

294 Z6OL6G Y.- M. BUNTING PROC. N. A. S. A PRELIMINARY NOTE ON TETRAMITUS, A STAGE IN THE LIFE CYCLE OF A COPROZOIC AMOEBA By MARTHA BUNTING DEPARTMENT OF ZOOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA Communicated July 24, 1922 In 1920 a study of the Entamoeba of the rat was begun and in a culture on artificial medium a number of Coprozoic amoeba appeared, one of which exhibited a flagellate phase which seems to be identical with Tetramitus rostratus Perty.1 The appearance of flagellate phases in cultures of Coprozoic amoeba (Whitmore,2 etc.) as well as of soil amoeba (Kofoid,1 Wilson,4 etc.) has been recorded a number of times, but the flagellates which appeared were relatively simple in organization and very transitory in occurrence. Fur- thermore, some of the simpler flagellates have been observed (Pascher5) to lose their flagella and become amoeboid. In the case here described, however, there is a transformation of a simple amoeba into a relatively complex flagellate which multiplies for several days then returns to the amoeboid condition and becomes encysted. Tetramitus rostratus has been studied by a number of investigators since its discovery in 1852, by Perty,' yet no one has given a full account of its life history. The lack of cysts in previous accounts, mentioned by Dobell and O'Connor,6 is explained by the transformation into an amoeba before encystment. It is believed that this animal presents the extreme in transformations of this sort and serves to emphasize the close relationship between amoebae and flagellates, and the need for careful studies of life cycles, in pure cultures where possible, in investigations of coprozoic and other Protozoa. -

Brown Algae and 4) the Oomycetes (Water Molds)

Protista Classification Excavata The kingdom Protista (in the five kingdom system) contains mostly unicellular eukaryotes. This taxonomic grouping is polyphyletic and based only Alveolates on cellular structure and life styles not on any molecular evidence. Using molecular biology and detailed comparison of cell structure, scientists are now beginning to see evolutionary SAR Stramenopila history in the protists. The ongoing changes in the protest phylogeny are rapidly changing with each new piece of evidence. The following classification suggests 4 “supergroups” within the Rhizaria original Protista kingdom and the taxonomy is still being worked out. This lab is looking at one current hypothesis shown on the right. Some of the organisms are grouped together because Archaeplastida of very strong support and others are controversial. It is important to focus on the characteristics of each clade which explains why they are grouped together. This lab will only look at the groups that Amoebozoans were once included in the Protista kingdom and the other groups (higher plants, fungi, and animals) will be Unikonta examined in future labs. Opisthokonts Protista Classification Excavata Starting with the four “Supergroups”, we will divide the rest into different levels called clades. A Clade is defined as a group of Alveolates biological taxa (as species) that includes all descendants of one common ancestor. Too simplify this process, we have included a cladogram we will be using throughout the SAR Stramenopila course. We will divide or expand parts of the cladogram to emphasize evolutionary relationships. For the protists, we will divide Rhizaria the supergroups into smaller clades assigning them artificial numbers (clade1, clade2, clade3) to establish a grouping at a specific level. -

Evolutionary History Predicts the Stability of Cooperation in Microbial Communities

ARTICLE Received 13 Aug 2013 | Accepted 9 Sep 2013 | Published 11 Oct 2013 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms3573 Evolutionary history predicts the stability of cooperation in microbial communities Alexandre Jousset1,2, Nico Eisenhauer3, Eva Materne1 & Stefan Scheu1 Cooperation fundamentally contributes to the success of life on earth, but its persistence in diverse communities remains a riddle, as selfish phenotypes rapidly evolve and may spread until disrupting cooperation. Here we investigate how evolutionary history affects the emergence and spread of defectors in multispecies communities. We set up bacterial communities of varying diversity and phylogenetic relatedness and measure investment into cooperation (proteolytic activity) and their vulnerability to invasion by defectors. We show that evolutionary relationships predict the stability of cooperation: phylogenetically diverse communities are rapidly invaded by spontaneous signal-blind mutants (ignoring signals regulating cooperation), while cooperation is stable in closely related ones. Maintenance of cooperation is controlled by antagonism against defectors: cooperators inhibit phylogenetically related defectors, but not distant ones. This kin-dependent inhibition links phylogenetic diversity and evolutionary dynamics and thus provides a robust mechanistic predictor for the persistence of cooperation in natural communities. 1 J.F. Blumenbach Institute of Zoology and Anthropology, Georg August University Go¨ttingen, Berliner Strae 28, 37073 Go¨ttingen, Germany. 2 Department of Ecology and Biodiversity, Utrecht University, Padualaan 8, 3584 CH Utrecht, The Netherlands. 3 Institute of Ecology, Friedrich-Schiller-University Jena, Dornburger Str. 159, 07743 Jena, Germany. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to A.J. (email: [email protected]). NATURE COMMUNICATIONS | 4:2573 | DOI: 10.1038/ncomms3573 | www.nature.com/naturecommunications 1 & 2013 Macmillan Publishers Limited. -

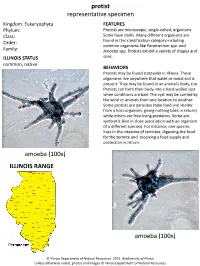

Protist Representative Specimen ILLINOIS RANGE Amoeba (100X)

protist representative specimen Kingdom: Eukaryophyta FEATURES Phylum: Protists are microscopic, single-celled, organisms. Class: Some have shells. Many different organisms are Order: found in this classification category including common organisms like Paramecium spp. and Family: Amoeba spp. Protists exhibit a variety of shapes and ILLINOIS STATUS sizes. common, native BEHAVIORS Protists may be found statewide in Illinois. These organisms live anywhere that water or moist soil is present. They may be found in an animal’s body, too. Protists can form their body into a hard-walled cyst when conditions are bad. The cyst may be carried by the wind or animals from one location to another. Some protists are parasites (take food and shelter from a host organism, giving nothing back in return) while others are free-living predators. Some are symbiotic (live in close association with an organism of a different species). For instance, one species lives in the intestine of termites, digesting the food for the termite and receiving a food supply and protection in return. amoeba (100x) ILLINOIS RANGE amoeba (100x) © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. 2021. Biodiversity of Illinois. Unless otherwise noted, photos and images © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. paramecia (100x) paramecia (40x) paramecium (400x) Aquatic Habitats bottomland forests; marshes; peatlands; rivers and streams; swamps; wet prairies and fens Woodland Habitats bottomland forests; coniferous forests; southern Illinois lowlands; upland deciduous forests Prairie and Edge Habitats black soil prairie; dolomite prairie; edge; gravel prairie; hill prairie; sand prairie; shrub prairie © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. 2021. Biodiversity of Illinois. Unless otherwise noted, photos and images © Illinois Department of Natural Resources.. -

Physarum Polycephalum (Plasmodial Slime Mold)

Physarum polycephalum (plasmodial slime mold) Species: polycephalum Genus: Physarum Family: Physaraceae Order: Physarales Class: Myxomycetes Phylum: Mycetozoa Kingdom: Amoebozoa Conditions for Customer Ownership We hold permits allowing us to transport these organisms. To access permit conditions, click here. Never purchase living specimens without having a disposition strategy in place. There are currently no USDA permits required for this organism. In order to protect our environment, never release a live laboratory organism into the wild. Primary Hazard Considerations Always wash your hands thoroughly before and after you handle your cultures, or anything it has touched. It is recommended to use gloves when working with mold, fungus, or bacteria. Availability Physarum is available year round. Care Habitat • Plasmodial stage are shipped in a Petri dish on Physarum agar with oats. Your Physarum should be bright yellow in color, and fan shaped. If your Physarum takes on a different appearance it may be contaminated. Contaminated cultures occur when a foreign specimen (something other than Physarum) makes its way onto your culture. This culture should be stored at room temperature in a dark place. The culture should be viable for about 1–2 weeks in its current container. • Sclerotia are hardened masses of irregular form consisting of many minute cell-like components. These are shipped on cut strips of filter paper in a tube. The culture should be stored at room temperature and can be stored in this stage for several months. Care: • Physarum is subcultured onto Physarum agar, and is incubated at room temperature or 25 °C. To maintain viability, plasmodial Physarum should be subcultured weekly. -

NAEGLERIA FOWLERI: BRAIN-EATING AMOEBA by the PHTA Recreational Water Quality Committee

TECH NOTES NAEGLERIA FOWLERI: BRAIN-EATING AMOEBA By the PHTA Recreational Water Quality Committee NAEGLERIA FOWLERI IS a 99.9% (a 3-log kill) of the amoeba in 9 and migrates along the olfactory nerve microscopic amoeba that grows in minutes (CT=9). to the brain. Once in the brain the warm lakes, ponds, streams and One outbreak in a swimming pool amoeba multiplies and causes PAM. other untreated fresh waters. (It did occur in one conventional pool and Naegleria has been detected in does not grow in salt water.) In rare lasted from 1962 to 1965 in Usti nad swimming pools with less than 1 ppm cases, this amoeba causes serious Labem, Czechoslovakia. During this free chlorine in France and Australia. illness for swimmers, entering the time period 16 deaths occurred due to There are no reported illnesses from brain and causing primary amebic infections from Naegleria. Over several these pools. meningoencephalitis (PAM), which is years it was discovered the pool had usually fatal. Since it was first reported a cracked false wall with a water-filled OCCURRENCE IN NATURE there have been a total of 145 cases in pocket that was not disinfected. The Naegleria fowleri is one of 40 species the U.S. Of these cases, 141 have been pool had been maintained at 80 to 86 of Naegleria but is the only one that fatal. In 2013 a new drug was found to degrees Fahrenheit. As the pool water causes illness in humans. It is one be an effective treatment if given early. level was raised for competitive event of the many microorganisms found it flushed the amoebae and organic in natural waters, particularly warm IS IT A HEALTH THREAT IN matter from behind the cracked wall waters. -

Exploration of the Propagation of Transpovirons Within Mimiviridae Reveals a Unique Example of Commensalism in the Viral World

The ISME Journal (2020) 14:727–739 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-019-0565-y ARTICLE Exploration of the propagation of transpovirons within Mimiviridae reveals a unique example of commensalism in the viral world 1 1 1 1 1 Sandra Jeudy ● Lionel Bertaux ● Jean-Marie Alempic ● Audrey Lartigue ● Matthieu Legendre ● 2 1 1 2 3 4 Lucid Belmudes ● Sébastien Santini ● Nadège Philippe ● Laure Beucher ● Emanuele G. Biondi ● Sissel Juul ● 4 2 1 1 Daniel J. Turner ● Yohann Couté ● Jean-Michel Claverie ● Chantal Abergel Received: 9 September 2019 / Revised: 27 November 2019 / Accepted: 28 November 2019 / Published online: 10 December 2019 © The Author(s) 2019. This article is published with open access Abstract Acanthamoeba-infecting Mimiviridae are giant viruses with dsDNA genome up to 1.5 Mb. They build viral factories in the host cytoplasm in which the nuclear-like virus-encoded functions take place. They are themselves the target of infections by 20-kb-dsDNA virophages, replicating in the giant virus factories and can also be found associated with 7-kb-DNA episomes, dubbed transpovirons. Here we isolated a virophage (Zamilon vitis) and two transpovirons respectively associated to B- and C-clade mimiviruses. We found that the virophage could transfer each transpoviron provided the host viruses were devoid of 1234567890();,: 1234567890();,: a resident transpoviron (permissive effect). If not, only the resident transpoviron originally isolated from the corresponding virus was replicated and propagated within the virophage progeny (dominance effect). Although B- and C-clade viruses devoid of transpoviron could replicate each transpoviron, they did it with a lower efficiency across clades, suggesting an ongoing process of adaptive co-evolution. -

Sir-Actin-Labelled Granules in Foraminifera: Patterns, Dynamics, and Hypotheses

Biogeosciences, 17, 995–1011, 2020 https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-17-995-2020 © Author(s) 2020. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. SiR-actin-labelled granules in foraminifera: patterns, dynamics, and hypotheses Jan Golen´ 1, Jarosław Tyszka1, Ulf Bickmeyer2, and Jelle Bijma2 1ING PAN – Institute of Geological Sciences, Polish Academy of Sciences, Research Centre in Kraków, Biogeosystem Modelling Group, Senacka 1, 31-002 Kraków, Poland 2AWI – Alfred-Wegener-Institut Helmholtz-Zentrum für Polar- und Meeresforschung, Am Handelshafen 12, 27570 Bremerhaven, Germany Correspondence: Jan Golen´ ([email protected]) Received: 10 May 2019 – Discussion started: 23 May 2019 Revised: 23 December 2019 – Accepted: 8 January 2020 – Published: 25 February 2020 Abstract. Recent advances in fluorescence imaging facilitate is based on the assumption that actin granules are analogous actualistic studies of organisms used for palaeoceanographic to tubulin paracrystals responsible for efficient transport of reconstructions. Observations of cytoskeleton organisation tubulin. Actin patches transported in that manner are most and dynamics in living foraminifera foster understanding of likely involved in maintaining shape, rapid reorganisation, morphogenetic and biomineralisation principles. This paper and elasticity of pseudopodial structures, as well as in adhe- describes the organisation of a foraminiferal actin cytoskele- sion to the substrate. Finally, our comparative studies suggest ton using in vivo staining based on fluorescent SiR-actin. that a large proportion of SiR-actin-labelled granules prob- Surprisingly, the most distinctive pattern of SiR-actin stain- ably represent fibrillar vesicles and elliptical fuzzy-coated ing in foraminifera is the prevalence of SiR-actin-labelled vesicles often identified in transmission electron microscope granules (ALGs) within pseudopodial structures.