Interim Eligibility Guidelines for Assessing the International Protection Needs of Asylum-Seekers from Cote D'ivoire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

C O M M U N I Q

MINISTERE DE LA CONSTRUCTION, DU LOGEMENT REPUBLIQUE DE COTE D'IVOIRE DE L’ASSAINISSEMENT ET DE L'URBANISME Union - Discipline - Travail LE MINISTRE Abidjan, le N ________/MCLAU/CAB/bfe C O M M U N I Q U E Le Ministre de la Construction, de l’Assainissement et de l’Urbanisme a le plaisir d’informer les usagers demandeurs d’arrêté de concession définitive, dont les noms sont mentionnés ci-dessous que les actes demandés ont été signés et transmis à la Conservation Foncière. Les intéressés sont priés de se rendre à la Conservation Foncière concernée en vue du paiement du prix d'aliénation du terrain ainsi que des droits et taxes y afférents. Cinq jours après le règlement du prix d'aliénation suivi de la publication de votre acte au livre foncier, vous vous présenterez pour son retrait au service du Guichet Unique du Foncier et de l'Habitat. -

To the Management of Surface Water Resources in the Ivory Coast Basin of the Aghien Lagoon

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research Volume 10, Issue 10, October-2019 1605 ISSN 2229-5518 Application of the water evaluation and planning model (WEAP) to the management of surface water resources in the Ivory Coast basin of the Aghien lagoon 1Dabissi NOUFÉ Djibril, 2ZAMBLE Armand Tra Bi, 1DIALLO Seydou, 1SORO Emile Gnénéyougo, 1DAO Amidou, 1DIOMANDE Souleymane, EFFEBI Kôkôh Rose, 1KAMAGATÉ Bamory, 1GONÉ Droh Laciné, 3PATUREL Jean-Emmanuel, 2MAHE Gil, 1GOULA Bi Tié Albert, 3SERVAT Éric. Abstract —Water, an essential element of life, is of paramount importance in our countries, where it is increasingly scarce and threatened; we are constantly maintained by news where pollution, scarcity, flooding are mixed. As a result of cur- rent rapid climatic and demographic changes, the management of water resources by human being is becoming one of the major challenges of the 21st century, as water becoming an increasingly limited resource. It will now be necessary to use with modera- tion. This study is part of the project "Aghien Lagoon" (Abidjan) and its potential in terms of safe tape water resources. Mega- lopolis of about six million inhabitants (RGPH, 2014), Abidjan encounters difficulties of access to safe tape water due to the de- cline of the underground reserves and the increase the demand related to urban growth. Thus, the Aghien lagoon, the largest freshwater reserve near Abidjan, has been identified by the State of Côte d'Ivoire as a potential source of additive production of safe tape water. However, urbanization continues to spread on the slopes of this basin, while, at the same time, market garden- ing is developing, in order to meet the demand. -

DIAGNOSTIC REVIEW of PUBLIC EXPENDITURE in the AGRICULTURAL SECTOR in CÔTE D’IVOIRE Public Disclosure Authorized Period 1999–2012

104089 Public Disclosure Authorized MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES AND FORESTS MINISTRY OF LIVESTOCK AND FISHERY RESOURCES DIAGNOSTIC REVIEW OF PUBLIC EXPENDITURE IN THE AGRICULTURAL SECTOR IN CÔTE D’IVOIRE Public Disclosure Authorized Period 1999–2012 Ismaël Ouédraogo, International Consultant Kama Berté, National Consultant Public Disclosure Authorized FINAL November 2014 Public Disclosure Authorized Table of Contents LIST OF FIGURES iii LIST OF TABLES iv ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS v EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 I. INTRODUCTION 16 Objectives of the APE Diagnostic Review ........................................................................................ 17 Methodology ...................................................................................................................................... 17 II. STRATEGIC CONTEXT OF THE DIAGNOSTIC REVIEW 19 National Strategic Context ................................................................................................................. 19 Sectoral Strategies .............................................................................................................................. 20 Institutional Framework ..................................................................................................................... 23 III. COFOG CLASSIFICATION AND THE AGRICULTURAL PUBLIC EXPENDITURE DATABASE 25 COFOG Classification for the Agricultural Sector ............................................................................ 25 The APE Database ............................................................................................................................ -

Liste Des Centres De Collecte Du District D'abidjan

LISTE DES CENTRES DE COLLECTE DU DISTRICT D’ABIDJAN Région : LAGUNES Centre de Coordination: ABIDJAN Nombre total de Centres de collecte : 774 ABIDJAN 01 ABOBO Nombre de Centres de collecte : 155 CODE CENTRE DE COLLECTE 001 EPV CATHOLIQUE ST GASPARD BERT 002 EPV FEBLEZY 003 GROUPE SCOLAIRE LE PROVENCIAL ABOBO 004 COLLEGE PRIVE DJESSOU 006 COLLEGE COULIBALY SANDENI 008 G.S. ANONKOUA KOUTE I 009 GROUPE SCOLAIRE MATHIEU 010 E-PP AHEKA 011 EPV ABRAHAM AYEBY 012 EPV SAHOUA 013 GROUPE SCOLAIRE EBENEZER 015 GROUPE SCOLAIRE 1-2-3-4-5 BAD 016 GROUPE SCOLAIRE SAINT MOISE 017 EPP AGNISSANKO III 018 EPV DIALOGUE ET DESTIN 2 019 EPV KAUNAN I 020 GROUPE SCOLAIRE ABRAHAM AYEBY 021 EPP GENDARMERIE 022 GROUPE SAINTE FOI ABIDJAN 023 G. S. LES AMAZONES 024 EPV AMAZONES 025 EPP PALMERAIE 026 EPV DIALOGUE 1 028 INSTITUT LES PREMICES 030 COLLEGE GRACE DIVINE 031 GROUPE SCOLAIRE RAIL 4 BAD B ET C 032 EPV DIE MORY 033 EPP SAGBE I (BOKABO) 034 EPP ATCHRO 035 EPV ANOUANZE 036 EPV SAINT PAUL 037 EPP N'SINMON 039 COLLEGE H TAZIEFE 040 EPV LESANGES-NOIRS 041 GROUPE SCOLAIRE ASSAMOI 045 COLLEGE ANADOR 046 EPV LA PROVIDENCE 047 EPV BEUGRE 048 GROUPE SCOLAIRE HOUANTOUE 049 EPV SAINT-CYR 050 GROUPE SCOLAIRE SAINTE JEANNE 051 GROUPE SCOLAIRE SAINTE ELISABETH 052 EPP PLATEAU-DOKUI BAD 054 GROUPE SCOLAIRE ABOBOTE ANNEXE 055 GROUPE SCOLAIRE FENDJE 056 GROUPE SCOLAIRE ABOBOTE 057 EPV CATHOLIQUE SAINT AUGUSTIN 058 GROUPE SCOLAIRE LES ORCHIDEES 059 CENTRE D'EDUCATION PRESCOLAIRE 060 EPV REUSSITE 061 EPP GISCARD D'ESTAING 062 EPP LES FLAMBOYANTS 063 GROUPE SCOLAIRE ASSEMBLEE -

Monthly Humanitarian Report November 2011

Côte d’Ivoire Rapport Humanitaire Mensuel Novembre 2011 Côte d’Ivoire Monthly Humanitarian Report November 2011 www.unocha.org The mission of the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) is to mobilize and coordinate effective and principled humanitarian action in partnership with national and international actors. Coordination Saves Lives • Celebrating 20 years of coordinated humanitarian action November 2011 Côte d’Ivoire Monthly Bulletin | 2 Côte d’Ivoire Monthly Humanitarian Report Coordination Saves Lives Coordination Saves Lives No. 2 | November 2011 HIGHLIGHTS Voluntary and spontaneous repatriation of Ivorian refugees from Liberia continues in Western Cote d’Ivoire. African Union (AU) delegation visited Duékoué, West of Côte d'Ivoire. Tripartite agreement signed in Lomé between Ivorian and Togolese Governments and the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR). Voluntary return of internally displaced people from the Duekoue Catholic Church to their areas of origin. World Food Program (WFP) published the findings of the post-distribution survey carried out from 14 to 21 October among 240 beneficiaries in 20 villages along the Liberian border (Toulépleu, Zouan- Hounien and Bin-Houyé). Child Protection Cluster in collaboration with Save the Children and UNICEF published The Vulnerabilities, Violence and Serious violations of Child Rights report. The Special Representative of the UN Secretary General on Sexual Violence in Conflict, Mrs. Margot Wallström on a six day visit to Côte d'Ivoire. I. GENERAL CONTEXT No major incident has been reported in November except for the clashes that broke out on 1 November between ethnic Guéré people and a group of dozos (traditional hunters). -

Côte D'ivoire Country Focus

European Asylum Support Office Côte d’Ivoire Country Focus Country of Origin Information Report June 2019 SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION European Asylum Support Office Côte d’Ivoire Country Focus Country of Origin Information Report June 2019 More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). ISBN: 978-92-9476-993-0 doi: 10.2847/055205 © European Asylum Support Office (EASO) 2019 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, unless otherwise stated. For third-party materials reproduced in this publication, reference is made to the copyrights statements of the respective third parties. Cover photo: © Mariam Dembélé, Abidjan (December 2016) CÔTE D’IVOIRE: COUNTRY FOCUS - EASO COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION REPORT — 3 Acknowledgements EASO acknowledges as the co-drafters of this report: Italy, Ministry of the Interior, National Commission for the Right of Asylum, International and EU Affairs, COI unit Switzerland, State Secretariat for Migration (SEM), Division Analysis The following departments reviewed this report, together with EASO: France, Office Français de Protection des Réfugiés et Apatrides (OFPRA), Division de l'Information, de la Documentation et des Recherches (DIDR) Norway, Landinfo The Netherlands, Immigration and Naturalisation Service, Office for Country of Origin Information and Language Analysis (OCILA) Dr Marie Miran-Guyon, Lecturer at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (EHESS), researcher, and author of numerous publications on the country reviewed this report. It must be noted that the review carried out by the mentioned departments, experts or organisations contributes to the overall quality of the report, but does not necessarily imply their formal endorsement of the final report, which is the full responsibility of EASO. -

“Abidjan: Floods, Displacements, and Corrupt Institutions”

“Abidjan: Floods, Displacements, and Corrupt Institutions” Abstract Abidjan is the political capital of Ivory Coast. This five million people city is one of the economic motors of Western Africa, in a country whose democratic strength makes it an example to follow in sub-Saharan Africa. However, when disasters such as floods strike, their most vulnerable areas are observed and consequences such as displacements, economic desperation, and even public health issues occur. In this research, I looked at the problem of flooding in Abidjan by focusing on their institutional response. I analyzed its institutional resilience at three different levels: local, national, and international. A total of 20 questionnaires were completed by 20 different participants. Due to the places where the respondents lived or worked when the floods occurred, I focused on two out of the 10 communes of Abidjan after looking at the city as a whole: Macory (Southern Abidjan) and Cocody (Northern Abidjan). The goal was to talk to the Abidjan population to gather their thoughts from personal experiences and to look at the data published by these institutions. To analyze the information, I used methodology combining a qualitative analysis from the questionnaires and from secondary sources with a quantitative approach used to build a word-map with the platform Voyant, and a series of Arc GIS maps. The findings showed that the international organizations responded the most effectively to help citizens and that there is a general discontent with the current local administration. The conclusions also pointed out that government corruption and lack of infrastructural preparedness are two major problems affecting the overall resilience of Abidjan and Ivory Coast to face this shock. -

Congrès AFSP 2009 Section Thématique 44 Sociologie Et Histoire Des Mécanismes De Dépacification Du Jeu Politique

Congrès AFSP 2009 Section thématique 44 Sociologie et histoire des mécanismes de dépacification du jeu politique Axe 3 Boris Gobille (ENS-LSH / Université de Lyon / Laboratoire Triangle) [email protected] Comment la stabilité politique se défait-elle ? La fabrique de la dépacification en Côte d’Ivoire, 1990-2000 Le diable gît dans les détails. Il arrive dans les conjonctures de crise politique que les luttes pour la définition des enjeux et pour la maîtrise de la direction à donner à l’incertitude politique en viennent à se synthétiser en un combat de mots. C’est ce qui se produit en Côte d’Ivoire l’été 2000, lorsque partis, presse et « société civile » s’agitent de façon virulente autour de deux conjonctions de coordination : le « et » et le « ou ». Le débat a pris une telle ampleur que la presse satirique s’en empare à son tour, maniant ironiquement le « ni ni » et le « jamais jamais ». Il ne s’agit évidemment pas de grammaire, mais de l’établissement, dans la nouvelle Constitution alors en discussion et appelée à faire l’objet d’un référendum, des conditions d’éligibilité aux élections générales, présidentielle et législatives, qui doivent se tenir à l’automne 2000 et qui sont censées clore la « transition » militaire ouverte par le coup d’Etat du 24 décembre 1999. Doit-on considérer que pour pouvoir candidater il faut être Ivoirien né de père « et » de mère eux-mêmes Ivoiriens, ou bien Ivoirien né de père « ou » de mère ivoirien ? Nul n’est alors dupe, dans ce débat, quant aux implications de la conjonction de coordination qui sera finalement choisie. -

Côte D'ivoire

Côte d’Ivoire Human Rights Violations in Abidjan during an Opposition Demonstration - March 2004 Human Rights Watch Briefing Paper, October 2004 Introduction................................................................................................................................... 1 Background to Events Surrounding the March 25, 2004 Demonstration ........................... 2 The Ivorian Government Position............................................................................................. 4 Violations by Pro-Government forces: Ivorian Police, Gendarmes and Army .................. 6 Violations by Pro-Government Forces: Militias and FPI Militants ..................................... 9 The Role of Armed Demonstrators.........................................................................................12 Mob Violence by the Demonstrators ......................................................................................14 Lack of Civilian Protection by Foreign Military Forces........................................................16 Legal Aspects ...............................................................................................................................17 Conclusion....................................................................................................................................18 Introduction The events associated with a demonstration in the Ivorian commercial capital of Abidjan by opposition groups planned for March 25, 2004, were accompanied by a deadly crackdown by government -

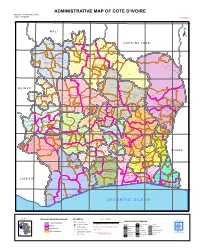

ADMINISTRATIVE MAP of COTE D'ivoire Map Nº: 01-000-June-2005 COTE D'ivoire 2Nd Edition

ADMINISTRATIVE MAP OF COTE D'IVOIRE Map Nº: 01-000-June-2005 COTE D'IVOIRE 2nd Edition 8°0'0"W 7°0'0"W 6°0'0"W 5°0'0"W 4°0'0"W 3°0'0"W 11°0'0"N 11°0'0"N M A L I Papara Débété ! !. Zanasso ! Diamankani ! TENGRELA [! ± San Koronani Kimbirila-Nord ! Toumoukoro Kanakono ! ! ! ! ! !. Ouelli Lomara Ouamélhoro Bolona ! ! Mahandiana-Sokourani Tienko ! ! B U R K I N A F A S O !. Kouban Bougou ! Blésségué ! Sokoro ! Niéllé Tahara Tiogo !. ! ! Katogo Mahalé ! ! ! Solognougo Ouara Diawala Tienny ! Tiorotiérié ! ! !. Kaouara Sananférédougou ! ! Sanhala Sandrégué Nambingué Goulia ! ! ! 10°0'0"N Tindara Minigan !. ! Kaloa !. ! M'Bengué N'dénou !. ! Ouangolodougou 10°0'0"N !. ! Tounvré Baya Fengolo ! ! Poungbé !. Kouto ! Samantiguila Kaniasso Monogo Nakélé ! ! Mamougoula ! !. !. ! Manadoun Kouroumba !.Gbon !.Kasséré Katiali ! ! ! !. Banankoro ! Landiougou Pitiengomon Doropo Dabadougou-Mafélé !. Kolia ! Tougbo Gogo ! Kimbirila Sud Nambonkaha ! ! ! ! Dembasso ! Tiasso DENGUELE REGION ! Samango ! SAVANES REGION ! ! Danoa Ngoloblasso Fononvogo ! Siansoba Taoura ! SODEFEL Varalé ! Nganon ! ! ! Madiani Niofouin Niofouin Gbéléban !. !. Village A Nyamoin !. Dabadougou Sinémentiali ! FERKESSEDOUGOU Téhini ! ! Koni ! Lafokpokaha !. Angai Tiémé ! ! [! Ouango-Fitini ! Lataha !. Village B ! !. Bodonon ! ! Seydougou ODIENNE BOUNDIALI Ponondougou Nangakaha ! ! Sokoro 1 Kokoun [! ! ! M'bengué-Bougou !. ! Séguétiélé ! Nangoukaha Balékaha /" Siempurgo ! ! Village C !. ! ! Koumbala Lingoho ! Bouko Koumbolokoro Nazinékaha Kounzié ! ! KORHOGO Nongotiénékaha Togoniéré ! Sirana -

Update No. 12 Côte D'ivoire Situation

Update No. 12 Côte d’Ivoire Situation 05 May 2011 HIGHLIGHTS • The inauguration of Mr. Alassane Ouattara as President of Côte d’Ivoire is scheduled to take place on 21 May. • The Ivorian Red Cross reported 60 dead bodies in the Yopougon neighbourhood of Abidjan after ongoing fighting between the “Forces Républicaines de Côte d’Ivoire” and the pro-Gbagbo militias. • On Monday 02 May, Laurent Gbagbo met with the South-African Archbishop, Desmond Tutu alongside former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan and former Irish President and UN human rights chief Mary Robinson in Korhogo in the north of Côte d’Ivoire. • The government has started paying civil service salaries, which were on hold during the conflict. • Long queues formed at banks that re-opened on 26 April, after having been closed for two and a half months. Armed robberies of the Banque de l’Habitat de Côte d’Ivoire and Group BNP Paribas vaults were reported on the same day. Community members in Awobo Village, Anyama (Abidjan) met UNHCR, ASAPSU and MESAD at the home of their chief to share the news and express the trauma inflicted upon their community during the period of conflict. (PERHAM S/ UNHCR/29 April 2011). Population Movement Burkina Guinea Sierra Country Guinea Mali Ghana Togo Benin Niger Nigeria Senegal Gambia Faso Bissau Leone Refugees/ Asylum 2,699 107 880 13,508 3,851 239 38 104 41 38 47 10 seekers Liberia 45,729 Ivorian refugees individually registered and 120,192 through the rapid emergency registration. In view of the volatile situation in Côte d’Ivoire, UNHCR is not yet in a position to provide exact figures. -

“The Best School” RIGHTS Student Violence, Impunity, and the Crisis in Côte D’Ivoire WATCH

Côte d’Ivoire HUMAN “The Best School” RIGHTS Student Violence, Impunity, and the Crisis in Côte d’Ivoire WATCH “The Best School” Student Violence, Impunity, and the Crisis in Côte d’Ivoire Copyright © 2008 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-312-9 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org May 2008 1-56432-312-9 “The Best School” Student Violence, Impunity, and the Crisis in Côte d’Ivoire Map of Côte d’Ivoire ...........................................................................................................2 Glossary of Acronyms......................................................................................................... 3 Summary ...........................................................................................................................6