Boom Bap Ex Machina: Hip-Hop Aesthetics and the Akai MPC

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

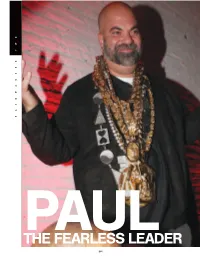

The Fearless Leader Fearless the Paul 196

TWO RAINMAKERS PAUL THE FEARLESS LEADER 196 ven back then, I was taking on far too many jobs,” Def Jam Chairman Paul Rosenberg recalls of his early career. As the longtime man- Eager of Eminem, Rosenberg has been a substantial player in the unfolding of the ‘‘ modern era and the dominance of hip-hop in the last two decades. His work in that capacity naturally positioned him to seize the reins at the major label that brought rap to the mainstream. Before he began managing the best- selling rapper of all time, Rosenberg was an attorney, hustling in Detroit and New York but always intimately connected with the Detroit rap scene. Later on, he was a boutique-label owner, film producer and, finally, major-label boss. The success he’s had thus far required savvy and finesse, no question. But it’s been Rosenberg’s fearlessness and commitment to breaking barriers that have secured him this high perch. (And given his imposing height, Rosenberg’s perch is higher than average.) “PAUL HAS Legendary exec and Interscope co-found- er Jimmy Iovine summed up Rosenberg’s INCREDIBLE unique qualifications while simultaneously INSTINCTS assessing the State of the Biz: “Bringing AND A REAL Paul in as an entrepreneur is a good idea, COMMITMENT and they should bring in more—because TO ARTISTRY. in order to get the record business really HE’S SEEN healthy, it’s going to take risks and it’s going to take thinking outside of the box,” he FIRSTHAND told us. “At its height, the business was run THE UNBELIEV- primarily by entrepreneurs who either sold ABLE RESULTS their businesses or stayed—Ahmet Ertegun, THAT COME David Geffen, Jerry Moss and Herb Alpert FROM ALLOW- were all entrepreneurs.” ING ARTISTS He grew up in the Detroit suburb of Farmington Hills, surrounded on all sides TO BE THEM- by music and the arts. -

Rakim the Militia Ii

The Militia Ii Rakim "A special guest" "It's the militia... It's the militia" This is a conquest, so I suggest you take a rest Or keep a breath, but definitely keep a vest on that chest Rymes I'm packin, just like a thug at a car-jackin' Shoot off your hat when I start cappin, this is no actin G-A-N-G, S-T-A double R And you don't want no trouble up in here, baby pa From the late-night drama, of the New York streets To the hoods of LA, real niggas likin Primo's beats Put suckers on glass, send em, back to class And kick hot shit, so we can stack the Johnny Cash I brought the God, Rakim, lyrically gunning you wanna dash? I got Dub C, from South C, what you doubt me? Travellin through warzones with my infrared microphone In the year One Mill, destroying, enemies chromozones Words burn through flesh, leavin nothing but skeletal You best pay resepect to the legends, boy I'm tellin you, Militia The illest Realest Representin Bringin the rukkus Let it be known The illest Realest Word up It's The Militia; Freddie Foxxx Makin a move, makin a move, who's that nigga thats makin a move? It's the Shadiest rhymin'-back, actin' a motherfucking fool Four-four packers, my jackets ?hittin the tag? saggin, baggin Foot on my rag, mess up a bag, leavin my enemies in bodybags You niggas was crackin, what y'all thought it wasn't gon' happen? Dub C and my East Coast sisters gettin together rappin Gun-clappin, chump smackin, kiss the ring of your highness Look while I'm in New York City, walkin with two of the Brooklyn's finest My two affiliates from the East -

Rapparen & Gourmetkocken Action Bronson Tillbaka Med Nytt Album

2015-03-03 10:31 CET Rapparen & gourmetkocken Action Bronson tillbaka med nytt album Hiphoparen och kocken Arian Asllani, aka Action Bronson, från Queens New York släpper nya albumet Mr. Wonderful den 25 mars. Bronson har med flertalet album, EP’s och mixtapes i ryggen gjort sig ett namn som en utav vår tids bästa rappare. Det sätt han levererar sitt artisteri och kombinerar sina rapfärdigheter med humor, självdistans och genomgående matreferenser gör honom unik i musikvärlden. Innan Bronson påbörjade sin karriär som rappare, som ursprungligen endast var en hobby för honom, var han en respekterad gourmetkock i New York City. Han drev sin egen online matlagnings show med titeln "Action In The Kitchen". Efter att han bröt benet i köket bestämde han sig för att enbart koncentrera sig på musiken. Debutalbumet Dr. Lecter släpptes 2011 såväl som ett par mixtapes, däribland Blue Chips. Sent år 2012 signade rapparen med Warner Music via medieföretaget VICE och för två år sedan släppte han EP’n Saaab Stories samt spelade på en av världens viktigaste musikfestivaler, nämligen Coachella Music Festival. Genom åren har han haft samarbeten med flera stor rappare såsom Wiz Khalifa, Raekwon, Eminem och Kendrick Lamar. Enligt Bronson är det kommande albumet hans bästa verk hittills. “I gave this my most incredible effort,” säger han. “If you listen to everything I’ve put out and then listen to this you’ll hear the steps that I’ve taken to go all out and show progression.” Singeln Baby Blue ft. Chance The Rapper, producerad av Mark Ronson, premiärspelades igår av Zane Lowe på BBC Radio 1. -

Hip Hop Style

Ear to the Street YO, CHUCK fashion BEATDOWN The shoe trends HIP HOP HAS ITS FASHION TENDENCY Can rappers protest without sounding Preachy or losing their message, often other people do not get the message essence LUIS VITTON MANOLO BIHANYK he fan-organized event was dubbed“Fiasco Friday,” but the event was Tanything but a disaster. Upward of 200 fans cheered, danced and rapped Lupe’s lyrics for hours before he arrived just shy of 3 p.m. CHAMPION SOUND to address the crowd. “So, y’all actually did it, J.DILLA huh?” he said to the audience. “The first thing I The late, great James dewitt yancey want to say is: Congratulations. The second thing aka J.Dilla lives this holiday with dillantology I want to say is: Thank you very much for put- HALFIGER ting on a very peaceful protest. The third thing I want to say is: Lasers is dropping March 8th!” ancey aka Jay Dee aka man. He inspires me to perfect Each remark from the MC drew a loud reaction. HIP RADII J Dilla was one of the my craft in every way. Dilla was The event was initially organized by two New Lmost influential produc- and will always be my hero.” Jersey natives, Matt Morrelli, 19, and Matt La ers of modern hip-hop and soul Before becoming one of hip- Corte, 17, as a way to help Lupe Fiasco score music. It’s possible that his hop’s greatest musical inspira- a release date for his long-delayed third album. HOP low-key attitude and devotion to tions, Dilla came up through the The rapper had been at odds with his label over craftsmanship, rather than desire ranks of the Detroit music scene. -

Hip-Hop's Diversity and Misperceptions

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Honors College Summer 8-2020 Hip-Hop's Diversity and Misperceptions Andrew Cashman Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors Part of the Music Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HIP-HOP’S DIVERSITY AND MISPERCEPTIONS by Andrew Cashman A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Degree with Honors (Anthropology) The Honors College University of Maine August 2020 Advisory Committee: Joline Blais, Associate Professor of New Media, Advisor Kreg Ettenger, Associate Professor of Anthropology Christine Beitl, Associate Professor of Anthropology Sharon Tisher, Lecturer, School of Economics and Honors Stuart Marrs, Professor of Music 2020 Andrew Cashman All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT The misperception that hip-hop is a single entity that glorifies wealth and the selling of drugs, and promotes misogynistic attitudes towards women, as well as advocating gang violence is one that supports a mainstream perspective towards the marginalized.1 The prevalence of drug dealing and drug use is not a picture of inherent actions of members in the hip-hop community, but a reflection of economic opportunities that those in poverty see as a means towards living well. Some artists may glorify that, but other artists either decry it or offer it as a tragic reality. In hip-hop trends build off of music and music builds off of trends in a cyclical manner. -

Cue Point Aesthetics: the Performing Disc Jockey In

CUE POINT AESTHETICS: THE PERFORMING DISC JOCKEY IN POSTMODERN DJ CULTURE By Benjamin De Ocampo Andres A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of Humboldt State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Sociology Committee Membership Dr. Jennifer Eichstedt, Committee Chair Dr. Renee Byrd, Committee Member Dr. Meredith Williams, Committee Member Dr. Meredith Williams, Graduate Coordinator May 2016 ABSTRACT CUE POINT AESTHETICS: THE PERFORMING DISC JOCKEY IN POSTMODERN DJ CULTURE Benjamin De Ocampo Andres This qualitative research explores how social relations and intersections of popular culture, technology, and gender present in performance DJing. The methods used were interviews with performing disc jockeys, observations at various bars, and live music venues. Interviews include both women and men from varying ages and racial/ethnic groups. Cultural studies/popular culture approaches are utilized as the theoretical framework, with the aid of concepts including resistance, hegemony, power, and subcultures. Results show difference of DJ preference between analog and digital formats. Gender differences are evident in performing DJ's experiences on and off the field due to patriarchy in the DJ scene. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and Foremost, I would like to thank my parents and immediate family for their unconditional support and love. You guys have always come through in a jam and given up a lot for me, big up. To "the fams" in Humboldt, you know who you are, thank you so much for holding me down when the time came to move to Arcata, and for being brothers from other mothers. A shout out to Burke Zen for all the jokes cracked, and cigarettes smoked, at "Chinatown." You help get me through this and I would have lost it along time ago. -

Mash out Posse's Latest Release Keeps It Real Minority Warnings For

PAGE 22 THE RETRIEVER WEEKLY FEATURES October 24, 2000 Mash Out Posse's Latest Release Keeps It Real "We 're the voice of the streets, and The subsequent EP, Handle Ur Bizness, arms and step lightly. we're .not letting that title go anywhere," and the release First Family showed that I pop shots at foes Album Review says Mash Out MOP still knew how .to touch a vein. Soren that don't entice me," -------- Posse's Lil' Fame in Baker of the LA Times reported that MOP, warns Billy Danze in by Jada lokeman the Brooklyn rap besides of course Run D.M.C. and the the opener "Welcome group's fourth and latest release, Warriorz, Beastie Boys, "were the first to enjoy to Brownsville." from Loud Records. · respect in the hip-hop community while Here, a bass line And they haven't gone anywhere. combining rock and rap in tl:ieir music." Of ·ripped from a '70s Despite changes in the industry as well as today's acts that have found success in car chase television the group's own label switch, MOP contin combining hip-hop and rock, namely Limp show is interspersed ues to deliver the hardcore in abundance. Bizkit, Korn and Kid Rock, she observes with a one-handed Although their trademark style of "undilut that "these rockers were beaten to the piano riff and pun~tu ed, unapolegetically underground ·sounds punch by MOP." In this period, they uti ated with a screech for hip hop purists (i-Music)" is difficult to lized less of DJ Premier's vast resources ing carpet bomb justify as responsible music, Warriorz dis and cultivated their own unique sound. -

Tap Tap Boom: a Multi-Touch floor Is Great for Creative Collaborative Music Production

Tap Tap Boom: A multi-touch floor is great for creative collaborative music production Jossekin Beilharz, Maximilian Schneider, Johan Uhle, David Wischner Hasso-Plattner Institute Prof.-Dr.-Helmert-Str. 2-3 14482 Potsdam, Germany fjossekin.beilharz, maximilian.schneider, johan.uhle, [email protected] ABSTRACT simultaneously. Therefore Tap Tap Boom offers a new per- Tap Tap Boom is a music production floor. It allows the user spective to music production. to create and edit music in an inspiring environment. Its si- ze encourages collaborative working. The user can use the input modes Step Sequencer, Groovebox and Pad to record music. One can arrange music in clips on a multi-track time- line. In addition to feet input we offer the usage of objects like bottles or saltshakers to interact with the system. Tap Tap Boom elevates creativity by providing a new approach to music production. Author Keywords music production, daw, multi-touch floor INTRODUCTION You can split electronic music production into three sequen- tial parts: In the beginning the musician composes. One ge- nerates and tests ideas. Inspiration and creativity play a key role at this stage. Afterwards the musician arranges the com- position and does the final recordings. The music is comple- Figure 1. On a large floor screen users can record and edit music colla- te. In the end the handcraft of mixing and mastering gives boratively using feet. the final touch to the sound and makes it ready for release. WALKTHROUGH There is a wide variety of tools which aid the process of Device electronic music production. -

Sonic Jihadâ•Flmuslim Hip Hop in the Age of Mass Incarceration

FIU Law Review Volume 11 Number 1 Article 15 Fall 2015 Sonic Jihad—Muslim Hip Hop in the Age of Mass Incarceration SpearIt Follow this and additional works at: https://ecollections.law.fiu.edu/lawreview Part of the Other Law Commons Online ISSN: 2643-7759 Recommended Citation SpearIt, Sonic Jihad—Muslim Hip Hop in the Age of Mass Incarceration, 11 FIU L. Rev. 201 (2015). DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.25148/lawrev.11.1.15 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by eCollections. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Law Review by an authorized editor of eCollections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 37792-fiu_11-1 Sheet No. 104 Side A 04/28/2016 10:11:02 12 - SPEARIT_FINAL_4.25.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 4/25/16 9:00 PM Sonic Jihad—Muslim Hip Hop in the Age of Mass Incarceration SpearIt* I. PROLOGUE Sidelines of chairs neatly divide the center field and a large stage stands erect. At its center, there is a stately podium flanked by disciplined men wearing the militaristic suits of the Fruit of Islam, a visible security squad. This is Ford Field, usually known for housing the Detroit Lions football team, but on this occasion it plays host to a different gathering and sentiment. The seats are mostly full, both on the floor and in the stands, but if you look closely, you’ll find that this audience isn’t the standard sporting fare: the men are in smart suits, the women dress equally so, in long white dresses, gloves, and headscarves. -

PCM 80 Dual FX Presets PCM 80 Dual FX Presets the 250 Dual FX Presets Are Organized in 5 Banks (X0-X4) of 50 Presets/Bank (Numbered 0.0 Ð 4.9)

PCM 80 Dual FX Presets PCM 80 Dual FX Presets The 250 Dual FX presets are organized in 5 Banks (X0-X4) of 50 presets/Bank (numbered 0.0 – 4.9). Press Program Banks repeatedly to cycle through the Banks. Turn SELECT to view the presets in the selected Bank. Press Load/✱ to load any displayed preset. Each preset has one or more parameters patched to the front panel ADJUST knob. This gives you instant access to some of the most interesting aspects of the effect. In addition, all of the presets marked with a T can be synchronized to tempo. To set the tempo, press the front panel Tap button twice in time with the beat. (Tempo can also be dialed in as a parameter value, or it can be determined by MIDI Clock.) Be sure to try these effects synchronized with MIDI sequence and drum patterns. Full descriptions of each preset are available in the Dual FX User Guide. 1.3 Mix>Drum>LP ADJUST: Hi Cut 0–127 3.3 15ips Echo ADJUST: Feedback 0–100 Program Bank X0 A stereo chamber optimized for drum submix, followed by a Stereo 15ips tape echo simulation. Listen to the sound change 24dB/octave lowpass filter. as it repeats. Stereo 1.4 Mix>Drum>HP ADJUST: Lo Cut 0–127 3.4 7.5ipsEkoRvb ADJUST: Feedback 0–100 The complement of Mix>Drum>LP with the drum chamber Stereo plate reverb fed by a 7.5ips tape echo simulation. Listen Presets 0.0-0.2 provide different room treatments for multiple followed by a 24dB/octave highpass filter. -

2011 – Cincinnati, OH

Society for American Music Thirty-Seventh Annual Conference International Association for the Study of Popular Music, U.S. Branch Time Keeps On Slipping: Popular Music Histories Hosted by the College-Conservatory of Music University of Cincinnati Hilton Cincinnati Netherland Plaza 9–13 March 2011 Cincinnati, Ohio Mission of the Society for American Music he mission of the Society for American Music Tis to stimulate the appreciation, performance, creation, and study of American musics of all eras and in all their diversity, including the full range of activities and institutions associated with these musics throughout the world. ounded and first named in honor of Oscar Sonneck (1873–1928), early Chief of the Library of Congress Music Division and the F pioneer scholar of American music, the Society for American Music is a constituent member of the American Council of Learned Societies. It is designated as a tax-exempt organization, 501(c)(3), by the Internal Revenue Service. Conferences held each year in the early spring give members the opportunity to share information and ideas, to hear performances, and to enjoy the company of others with similar interests. The Society publishes three periodicals. The Journal of the Society for American Music, a quarterly journal, is published for the Society by Cambridge University Press. Contents are chosen through review by a distinguished editorial advisory board representing the many subjects and professions within the field of American music.The Society for American Music Bulletin is published three times yearly and provides a timely and informal means by which members communicate with each other. The annual Directory provides a list of members, their postal and email addresses, and telephone and fax numbers. -

2019 JUNO Award Nominees

2019 JUNO Award Nominees JUNO FAN CHOICE AWARD (PRESENTED BY TD) Alessia Cara Universal Avril Lavigne BMG*ADA bülow Universal Elijah Woods x Jamie Fine Big Machine*Universal KILLY Secret Sound Club*Independent Loud Luxury Armada Music B.V.*Sony NAV XO*Universal Shawn Mendes Universal The Weeknd The Weeknd XO*Universal Tory Lanez Interscope*Universal SINGLE OF THE YEAR Growing Pains Alessia Cara Universal Not A Love Song bülow Universal Body Loud Luxury Armada Music B.V.*Sony In My Blood Shawn Mendes Universal Pray For Me The Weeknd, Kendrick Lamar Top Dawg Ent*Universal INTERNATIONAL ALBUM OF THE YEAR Camila Camila Cabello Sony Invasion of Privacy Cardi B Atlantic*Warner Red Pill Blues Maroon 5 Universal beerbongs & bentleys Post Malone Universal ASTROWORLD Travis Scott Sony ALBUM OF THE YEAR (SPONSORED BY MUSIC CANADA) Darlène Hubert Lenoir Simone* Select These Are The Days Jann Arden Universal Shawn Mendes Shawn Mendes Universal My Dear Melancholy, The Weeknd The Weeknd XO*Universal Outsider Three Days Grace RCA*Sony ARTIST OF THE YEAR (PRESENTED WITH APPLE MUSIC) Alessia Cara Universal Michael Bublé Warner Shawn Mendes Universal The Weeknd The Weeknd XO*Universal Tory Lanez Interscope*Universal GROUP OF THE YEAR (PRESENTED WITH APPLE MUSIC) Arkells Arkells*Universal Chromeo Last Gang*eOne Metric Metric Music*Universal The Sheepdogs Warner Three Days Grace RCA*Sony January 29, 2019 Page 1 of 9 2019 JUNO Award Nominees