Ray Charles (Ray Charles Peterson) Liver Disease

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To Sammy Davis, Jr. the Martin Luther King, Jr. Papers Project

20 Dec will have God’s guidance as she sets out on this sacred and serious responsibility 1960 of calling a pastor. Sincerely yours, Martin Luther King, Jr. MLK. m TLc. MLKP-MBU: Box 69. The Martin Luther King, Jr. Papers Project To Sammy Davis, Jr. 20 December 1960 [Atlanta, Ga.] King thanks Davis for his “wonabful support” of the upcoming 2 7January 1961 Carnegie Hall “Tribute to Martin Luther King, Jr.”’ King also praises aspiring playwright Oscar Brown’s musical Kicks & Go. for its portrayal of “the conjliGt of soul, the moral choices that confront our people, both Negro and white.” Mr. Sammy Davis, Jr. Sherry-Netherland Hotel 5th Avenue at 59th Street New York 2 2, New York Dear Sammy: I have been meaning to write you for quite some time. A sojourn in jail and a trip to Nigeria among other tasks have kept be behind. When I solicited your help for our struggle almost two months ago, I did not ex- pect so creative and fulsome a response. All of us are inspired by your wondei-ful support and the Committee is busily engaged in the preparations forJanuary 27th. I hope I can convey our appreciation to you with the warmth which we feel it. In the midst of one of my usual crowded sojourns in New York, I had the op- portunity to hear the play, “Kicks and Co.” by Oscar Brown at the invitation of the Nemiroffs, at whose home I have previously been a guest.2 I learned of your in- terest in it and I am deeply pleased. -

AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long Adele Rolling in the Deep Al Green

AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long Adele Rolling in the Deep Al Green Let's Stay Together Alabama Dixieland Delight Alan Jackson It's Five O'Clock Somewhere Alex Claire Too Close Alice in Chains No Excuses America Lonely People Sister Golden Hair American Authors The Best Day of My Life Avicii Hey Brother Bad Company Feel Like Making Love Can't Get Enough of Your Love Bastille Pompeii Ben Harper Steal My Kisses Bill Withers Ain't No Sunshine Lean on Me Billy Joel You May Be Right Don't Ask Me Why Just the Way You Are Only the Good Die Young Still Rock and Roll to Me Captain Jack Blake Shelton Boys 'Round Here God Gave Me You Bob Dylan Tangled Up in Blue The Man in Me To Make You Feel My Love You Belong to Me Knocking on Heaven's Door Don't Think Twice Bob Marley and the Wailers One Love Three Little Birds Bob Seger Old Time Rock & Roll Night Moves Turn the Page Bobby Darin Beyond the Sea Bon Jovi Dead or Alive Living on a Prayer You Give Love a Bad Name Brad Paisley She's Everything Bruce Springsteen Glory Days Bruno Mars Locked Out of Heaven Marry You Treasure Bryan Adams Summer of '69 Cat Stevens Wild World If You Want to Sing Out CCR Bad Moon Rising Down on the Corner Have You Ever Seen the Rain Looking Out My Backdoor Midnight Special Cee Lo Green Forget You Charlie Pride Kiss an Angel Good Morning Cheap Trick I Want You to Want Me Christina Perri A Thousand Years Counting Crows Mr. -

4 Non Blondes What's up Abba Medley Mama

4 Non Blondes What's Up Abba Medley Mama Mia, Waterloo Abba Does Your Mother Know Adam Lambert Soaked Adam Lambert What Do You Want From Me Adele Million Years Ago Adele Someone Like You Adele Skyfall Adele Turning Tables Adele Love Song Adele Make You Feel My Love Aladdin A Whole New World Alan Silvestri Forrest Gump Alanis Morissette Ironic Alex Clare I won't Let You Down Alice Cooper Poison Amy MacDonald This Is The Life Amy Winehouse Valerie Andreas Bourani Auf Uns Andreas Gabalier Amoi seng ma uns wieder AnnenMayKantenreit Barfuß am Klavier AnnenMayKantenreit Oft Gefragt Audrey Hepburn Moonriver Avicii Addicted To You Avicii The Nights Axwell Ingrosso More Than You Know Barry Manilow When Will I Hold You Again Bastille Pompeii Bastille Weight Of Living Pt2 BeeGees How Deep Is Your Love Beatles Lady Madonna Beatles Something Beatles Michelle Beatles Blackbird Beatles All My Loving Beatles Can't Buy Me Love Beatles Hey Jude Beatles Yesterday Beatles And I Love Her Beatles Help Beatles Let It Be Beatles You've Got To Hide Your Love Away Ben E King Stand By Me Bill Withers Just The Two Of Us Bill Withers Ain't No Sunshine Billy Joel Piano Man Billy Joel Honesty Billy Joel Souvenier Billy Joel She's Always A Woman Billy Joel She's Got a Way Billy Joel Captain Jack Billy Joel Vienna Billy Joel My Life Billy Joel Only The Good Die Young Billy Joel Just The Way You Are Billy Joel New York State Of Mind Birdy Skinny Love Birdy People Help The People Birdy Words as a Weapon Bob Marley Redemption Song Bob Dylan Knocking On Heaven's Door Bodo -

Mayodan High School Yearbook, "The Anchor"

» :-.i.jV Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/anchor1958mayo ^he eAncko ,,: ^ . 1958 CHARLOTTE GANN - Editor-in-Chief SHIRLEY EASTER Assistant Editor MILDRED WHITE Sales Manager BETTY S. WILKINS Advertising MONTSIE ALLRED Class Editor FRANKIE CARLTON Picture Editor ROGER TAYLOR Art Editor UDELL WESTON Sports Editor JIMMY GROGAN Feature Editor foreword The Senior Class of '58 presents this ANCHOR as a token of our appreciation to all who have helped us progress through the past years, especially our parents, teach- ers, fellow students, and Mr. Duncan. success, It is our sincere hope that your lives may be filled with happiness and and that you will continue to manifest a spirit of loyalty to Mayodan High School. SHIRLEY EASTER CHARLOTTE GANN ^Dedication To our parents, who, in the process of rearing us, have picked us up when we have fallen, pushed us when we needed pushing, and have tried to understand o u r problems when on one else would listen to us! Because of their faithfulness, understanding, and undying love, for which we feel so deeply grateful, we dedicate to them our annual, the ANCHOR of 1958. The Seniors ^iicfk Oc/tocl faculty Not Pictured HATTIE RUTH HYDER ELLIOTT F. DUNCAN VIOLET B. SULEY B. S., A. S. T. C. A. B., U. N. C. A. B., Wisconsin University Home Economics Principal Biology Not Pictured OTIS J. STULTZ IRMA S. CREWS HENRY C. M. WHITAKER B. A., Elon College B. A., Winthrop College A. B., High Point College Business Administration A. B., High Point College Spanish, Social Studies, Band Mathematics, English MAUD G. -

The 2016 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2016 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters

04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS 3/25/16 11:58 AM Page 1 The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts DAVID M. RUBENSTEIN , Chairman DEBORAH F. RUTTER , President CONCERT HALL Monday Evening, April 4, 2016, at 8:00 The Kennedy Center and the National Endowment for the Arts present The 2016 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2016 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters GARY BURTON WENDY OXENHORN PHAROAH SANDERS ARCHIE SHEPP Jason Moran is the Kennedy Center’s Artistic Director for Jazz. WPFW 89.3 FM is a media partner of Kennedy Center Jazz. Patrons are requested to turn off cell phones and other electronic devices during performances. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not allowed in this auditorium. 04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS 3/25/16 11:58 AM Page 2 2016 NEA JAZZ MASTERS TRIBUTE CONCERT Hosted by JASON MORAN, pianist and Kennedy Center artistic director for jazz With remarks from JANE CHU, chairman of the NEA DEBORAH F. RUTTER, president of the Kennedy Center THE 2016 NEA JAZZ MASTERS Performances by NEA JAZZ MASTERS: CHICK COREA, piano JIMMY HEATH, saxophone RANDY WESTON, piano SPECIAL GUESTS AMBROSE AKINMUSIRE, trumpeter LAKECIA BENJAMIN, saxophonist BILLY HARPER, saxophonist STEFON HARRIS, vibraphonist JUSTIN KAUFLIN, pianist RUDRESH MAHANTHAPPA, saxophonist PEDRITO MARTINEZ, percussionist JASON MORAN, pianist DAVID MURRAY, saxophonist LINDA OH, bassist KARRIEM RIGGINS, drummer and DJ ROSWELL RUDD, trombonist CATHERINE RUSSELL, vocalist 04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS -

HIT the ROAD JACK Lyrics by Ray Charles

HIT THE ROAD JACK Lyrics by Ray Charles (Hit the road Jack and don't you come back no more, no more, no more, no more.) (Hit the road Jack and don't you come back no more.) What you say? (Hit the road Jack and don't you come back no more, no more, no more, no more.) (Hit the road Jack and don't you come back no more.) Woah Woman, oh woman, don't treat me so mean, You're the meanest old woman that I've ever seen. I guess if you said so I'd have to pack my things and go. (That's right) (Hit the road Jack and don't you come back no more, no more, no more, no more.) (Hit the road Jack and don't you come back no more.) What you say? (Hit the road Jack and don't you come back no more, no more, no more, no more.) (Hit the road Jack and don't you come back no more.) Now baby, listen baby, don't ya treat me this-a way Cause I'll be back on my feet some day. (Don't care if you do 'cause it's understood) (you ain't got no money you just ain't no good.) Well, I guess if you say so I'd have to pack my things and go. (That's right) (Hit the road Jack and don't you come back no more, no more, no more, no more.) (Hit the road Jack and don't you come back no more.) What you say? (Hit the road Jack and don't you come back no more, no more, no more, no more.) (Hit the road Jack and don't you come back no more.) Well (don't you come back no more.) Uh, what you say? (don't you come back no more.) I didn't understand you (don't you come back no more.) You can't mean that (don't you come back no more.) Oh, now baby, please (don't you come back no more.) What you tryin' to do to me? (don't you come back no more.) Oh, don't treat me like that (don't you come back no more.) . -

Instead Draws Upon a Much More Generic Sort of Free-Jazz Tenor Saxophone Musical Vocabulary

Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. DELFEAYO MARSALIS NEA Jazz Master (2011) Interviewee: Delfeayo Marsalis (July 28, 1965 - ) Interviewer: Anthony Brown with recording engineer Ken Kimery Date: January 13, 2011 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History Description: Transcript, 38 pp. Brown: Ferdinand Delfeayo Marsalis. Good to see you again. Marsalis: You too, brother. Brown: It’s been, when? – since you were working with Max and the So What brass quintet. So that was about 2000, 2001? Marsalis: That was. Brown: So that was the last time we spent some time together. Marsalis: Had a couple of chalupas since then. Brown: I knew you had to get that in there. First of all, we reconnected just the other night over – Tuesday night over at the Jazz Masters Award at Lincoln Center. So, what did you think? Did you have a good time? Marsalis: I did, to be around the true legends and masters of jazz. It was inspiring and humbling, and they’re cool too. Brown: What do you think about receiving the award? For additional information contact the Archives Center at 202.633.3270 or [email protected] 1 Marsalis: I still feel I might be on the young side for that, but I think that my life has been, so far, dedicated to jazz and furthering the cause of jazz, and it’s something that I hope to keep doing to my last days. Brown: We’ll go ahead and start the formal interview. -

November/December 2005 Issue 277 Free Now in Our 31St Year

jazz &blues report november/december 2005 issue 277 free now in our 31st year www.jazz-blues.com Sam Cooke American Music Masters Series Rock & Roll Hall of Fame & Museum 31st Annual Holiday Gift Guide November/December 2005 • Issue 277 Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum’s 10th Annual American Music Masters Series “A Change Is Gonna Come: Published by Martin Wahl The Life and Music of Sam Cooke” Communications Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Inductees Aretha Franklin Editor & Founder Bill Wahl and Elvis Costello Headline Main Tribute Concert Layout & Design Bill Wahl The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and sic for a socially conscientious cause. He recognized both the growing popularity of Operations Jim Martin Museum and Case Western Reserve University will celebrate the legacy of the early folk-rock balladeers and the Pilar Martin Sam Cooke during the Tenth Annual changing political climate in America, us- Contributors American Music Masters Series this ing his own popularity and marketing Michael Braxton, Mark Cole, November. Sam Cooke, considered by savvy to raise the conscience of his lis- Chris Hovan, Nancy Ann Lee, many to be the definitive soul singer and teners with such classics as “Chain Gang” Peanuts, Mark Smith, Duane crossover artist, a model for African- and “A Change is Gonna Come.” In point Verh and Ron Weinstock. American entrepreneurship and one of of fact, the use of “A Change is Gonna Distribution Jason Devine the first performers to use music as a Come” was granted to the Southern Chris- tian Leadership Conference for ICON Distribution tool for social change, was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in the fundraising by Cooke and his manager, Check out our new, updated web inaugural class of 1986. -

Multimillion-Selling Singer Crystal Gayle Has Performed Songs from a Wide Variety of Genres During Her Award-Studded Career, B

MultiMillion-selling singer Crystal Gayle has performed songs from a wide variety of genres during her award-studded career, but she has never devoted an album to classic country music. Until now. You Don’t Know Me is a collection that finds the acclaimed stylist exploring the songs of such country legends as George Jones, Patsy Cline, Buck Owens and Eddy Arnold. The album might come as a surprise to those who associate Crystal with an uptown sound that made her a star on both country and adult-contemporary pop charts. But she has known this repertoire of hardcore country standards all her life. “This wasn’t a stretch at all,” says Crystal. “These are songs I grew up singing. I’ve been wanting to do this for a long time. “The songs on this album aren’t songs I sing in my concerts until recently. But they are very much a part of my history.” Each of the selections was chosen because it played a role in her musical development. Two of them point to the importance that her family had in bringing her to fame. You Don’t Know Me contains the first recorded trio vocal performance by Crystal with her singing sisters Loretta Lynn and Peggy Sue. It is their version of Dolly Parton’s “Put It Off Until Tomorrow.” “You Never Were Mine” comes from the pen of her older brother, Jay Lee Webb (1937-1996). The two were always close. Jay Lee was the oldest brother still living with the family when their father passed away. -

Jeremy Sassoon – Solo Playlist

JEREMY SASSOON – SOLO PLAYLIST Jazz/Swing Ain't misbehavin' Aint that a kick in the head All of me All the way Almost like being in love A nightingale sang in Berkeley square As time goes by At last Autumn leaves Beyond the sea Body and soul Bye bye blackbird Cheek to Cheek Come fly with me Corcovado Cry me a river Don’t get around much anymore Everytime we say goodbye Feeling good Fever Fly me to the moon Foggy day Georgia on my mind Girl from Ipanema God bless the child Have you met Miss Jones I can't give you anything but love I get a kick out of you I left my heart in San Francisco I only have eyes for you Is you is or is you ain’t my baby It don't mean a thing It had to be you It’s alright with me It’s only a paper moon I’ve got you under my skin I wish I knew how it would feel to be free (Film 2011) Let’s call the whole thing off Let’s do it, let’s fall in love Let’s face the music and dance Let’s fall in love Let there be love Love me or leave me Lullaby of birdland Mack the knife Makin whoopee Misty Moonglow Moon river Mr Bojangles My baby just cares for me My favourite things My funny valentine My romance My way Night and day One note samba On the sunny side of the street Orange coloured sky Our love is here to stay Over the rainbow Satin doll Shadow of your smile Smile So danco samba Summertime Sway Take the A train Tenderly The lady is a tramp The look of love The nearness of you The way you look tonight They can’t take that away from me Unforgettable When I fall in love You make me feel so young Piano Bar/Pop/Easy Listening -

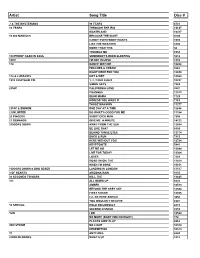

Copy UPDATED KAREOKE 2013

Artist Song Title Disc # ? & THE MYSTERIANS 96 TEARS 6781 10 YEARS THROUGH THE IRIS 13637 WASTELAND 13417 10,000 MANIACS BECAUSE THE NIGHT 9703 CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS 1693 LIKE THE WEATHER 6903 MORE THAN THIS 50 TROUBLE ME 6958 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL SOMEBODY'S BEEN SLEEPING 5612 10CC I'M NOT IN LOVE 1910 112 DANCE WITH ME 10268 PEACHES & CREAM 9282 RIGHT HERE FOR YOU 12650 112 & LUDACRIS HOT & WET 12569 1910 FRUITGUM CO. 1, 2, 3 RED LIGHT 10237 SIMON SAYS 7083 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 3847 CHANGES 11513 DEAR MAMA 1729 HOW DO YOU WANT IT 7163 THUGZ MANSION 11277 2 PAC & EMINEM ONE DAY AT A TIME 12686 2 UNLIMITED DO WHAT'S GOOD FOR ME 11184 20 FINGERS SHORT DICK MAN 7505 21 DEMANDS GIVE ME A MINUTE 14122 3 DOORS DOWN AWAY FROM THE SUN 12664 BE LIKE THAT 8899 BEHIND THOSE EYES 13174 DUCK & RUN 7913 HERE WITHOUT YOU 12784 KRYPTONITE 5441 LET ME GO 13044 LIVE FOR TODAY 13364 LOSER 7609 ROAD I'M ON, THE 11419 WHEN I'M GONE 10651 3 DOORS DOWN & BOB SEGER LANDING IN LONDON 13517 3 OF HEARTS ARIZONA RAIN 9135 30 SECONDS TO MARS KILL, THE 13625 311 ALL MIXED UP 6641 AMBER 10513 BEYOND THE GREY SKY 12594 FIRST STRAW 12855 I'LL BE HERE AWHILE 9456 YOU WOULDN'T BELIEVE 8907 38 SPECIAL HOLD ON LOOSELY 2815 SECOND CHANCE 8559 3LW I DO 10524 NO MORE (BABY I'MA DO RIGHT) 178 PLAYAS GON' PLAY 8862 3RD STRIKE NO LIGHT 10310 REDEMPTION 10573 3T ANYTHING 6643 4 NON BLONDES WHAT'S UP 1412 4 P.M. -

Page 1 Valentine's Day.Indd

THE BALL STATE MONDAY February 14, 2005 Vol. 84, Issue 98 DAILYMUNCIEDAILY WWW.BSUDAILYNEWS.COM NEWSNEWS INDIANA INTERNATIONAL DNNEWS See what is going on across the nation. NEW YORK Shiites, New generation of Manhattan madams allegedly Kurds made mint off oldest profession (AP) — The blue blood sweep Mayflower Madam argued that the oldest profession was merely ‘‘naughty,’’ not criminal. More than two decades after her high-priced service was election shut down, police are cracking Bush congratulates down on a new generation of Manhattan madams who alleg- Iraqis for ‘defying edly became wealthy by running prostitution rings for big spend- terrorist threats’ ers, and like Mayflower Madam Robert H. Reid ■ Associated Press Sydney Biddle Barrows, one of them wonders what all the fuss BAGHDAD, Iraq — Clergy- is about. backed Shiites and indepen- ‘‘It’s the oldest game in town,’’ dence-minded Kurds swept to victory in Iraq’s landmark elec- Julie Moya said before surren- tion, propelling to power the dering to a vice squad late last groups that suffered most un- month. ‘‘We don’t hurt anyone. der Saddam Hussein and forc- We just offer pleasure.’’ ing Sunni Arabs to the margins Prostitution ‘‘has become the DN Illustration / CHAD YODER for the first time in modern crime du jour,’’ said Moya’s at- history, according to final re- torney, Dan Ollen. sults released Sunday. But the Shiites’ 48 percent ‘‘There’s a tremendous amount of the vote is far short of the of money involved,’’ said Inspec- two-thirds majority needed to tor James P. O’Neill, head of the control the New York Police Department’s Agenda 275-member vice enforcement division.