Loathsome Beasts: Images of Reptiles and Amphibians in Art and Science Kay Etheridge Gettysburg College

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maria Sibylla Merian and Metamorphosis

PUBLISHED: 21 FEBRUARY 2017 | VOLUME: 1 | ARTICLE NUMBER: 0074 books & arts Maria Sibylla Merian and metamorphosis ANNIVERSARY Despite the fact that art is subjective and concerned with aesthetics, whereas science is an objective enterprise based on observation and experimentation, a combination of these dissimilar activities can yield surprising results. A small group of world-class biologists have also been gi"ed artists. #is group includes the German botanist Julius Sachs, founder of experimental plant physiology 1; the zoologist Ernst Haeckel; and, perhaps less known, the entomologist Maria Sibylla Merian (Fig. 1), the tricentenary of whose death falls this year. Merian made signi%cant contributions to the foundation of developmental biology and ecology, but has been neglected. Born in 1647 in Frankfurt (Main), Germany, Merian Figure 2 | Merian’s paintings. Left, watercolour image on the title page of Merian’s first scientific book developed her skill painting insects and Der Raupen Wunderbare Verwandelung und Sonderbare Blumen-nahrung (The Wonderful Metamorphosis plants under the guidance of her stepfather, of Caterpillars and Strange Flower Nourishment). Merian described the complete life cycles of numerous the artist Jacob Marrel. At the age of 13, she insect species, including their destructive feeding behaviour on host plants, and rejected the then was already an accomplished painter, with popular idea of an origin of insects via ‘spontaneous generation’. Image courtesy of U. Kutschera. Right, an overwhelming drive to study nature. Merian’s realistic documentation of the “struggle for existence” in a natural world that was, in her view, Merian started to collect insects and plants God’s creation. -

Maria Sibylla Merian's Research Journey to Suriname

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Resources Supplementary Information August 2017 To See for Herself: Maria Sibylla Merian’s Research Journey to Suriname: 1699-1701 Catherine Grimm Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sophsupp_resources Part of the German Literature Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Grimm, Catherine, "To See for Herself: Maria Sibylla Merian’s Research Journey to Suriname: 1699-1701" (2017). Resources. 6. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sophsupp_resources/6 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Supplementary Information at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Resources by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. To See for Herself: Maria Sibylla Merian’s Research Journey to Suriname: 1699-1701 By Catherine Grimm Maria Sibylla Merian was born on April, 2 1647 in Frankfurt am Main, one year before the signing of the Peace treaties of Westphalia and the end of the Thirty Years War. Her 55 year old father, the famous artist, engraver and publisher Matthäus Merian, died when she was three. About a year after his death, Maria’s mother, Johanna Sibylla, remarried the painter and art- dealer Jacob Marrel whose family had moved to Frankfurt from the town of Frankenthal when he was 10, and who also had lived for a number of years in Utrecht, before returning to Frankfurt in 1651. He had been a student of the well-known still life artist Geog Flegel as well as the Dutch painter Jan Davidzs de Heem.1 From an early age, Merian appears to have been surprisingly adept at pursuing her own interests, without arousing the disapproval of her immediate social environment. -

Bl12-2Pgs.Pdf

Volume 12, Number 2 $8.50 ARTISTS’ BOOKSbBOOKBINDINGbPAPERCRAFTbCALLIGRAPHY Volume 12, Number 2, February 2015. 3 Creating Double-Stroke Letterforms by Martin Jackson 8 Dancing Letters Scholarship Fund 12 Creating a Scroll-Tip Pilot Parallel Pen by Carol DuBosch 14 Between Verse and Vision by Risa Gettler 22 Heraldry for Calligraphy by Helen Scholes 28 Spinning Letters by Judy Black, Susan Gunter, and Marilyn Rice 30 A Passionate Gallery 37 New Tools & Materials 38 Passionate Pen Envelopes 40 Leporello Accordion Book by Carol DuBosch 42 Contributors / credits 47 Subscription information A Few Excerpts from the Now Intergalactic Song Fest and Cosmic Miscelany. 2014. Risa Gettler. Hand- lettered and illustrated manuscript book of nineteen poems by John S. Tumlin. 40 pages, images and text on recto pages only. Leather binding is by Edna Wright. Each page is held in an open-front sleeve that is sewn into the binding. The front of the sleeve serves as a frame for its book page (which can be removed). 22" x 13" x 4". Photo by Risa Gettler. “Between Verse and Vision,” page 14. Bound & Lettered b Spring 2015 1 All calligraphy shown in this article is by the author. CREATING DOUBLE-STROKE LETTERFORMS BY MARTIN JACKSON There are two methods to create double-stroke letterforms. One is to use a scroll (or split) nib or pen. These are made to automatically produce double strokes – the pen/nib does it for you. A variety of writing instruments offer scroll versions: Mitchell makes six differ- ent scroll dip pen nibs, Manuscript offers two different scroll nibs (Scroll 4 and Scroll 6) for some of its fountain pens, and four of the Automatic pens have split nibs (numbers 7, 8, 9, and 10). -

Predation of Oscaecilia Bassleri (Gymnophiona: Caecilidae) by Anilius Scytale (Serpentes: Aniliidae) in Southeast Peru

Nota Cuad. herpetol. 30 (1): 29-30 (2016) Predation of Oscaecilia bassleri (Gymnophiona: Caecilidae) by Anilius scytale (Serpentes: Aniliidae) in southeast Peru Jaime Villacampa 1, Andrew Whitworth1, 2 1 The Crees Foundation, Urbanización Mariscal Gamarra B-5 Zona 1 2da Etapa, Cusco, Peru. 2 Institute of Biodiversity, Animal Health and Comparative Medicine, College of Medical, Veterinary and Life Sciences, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, G12 8QQ, UK. Recibida: 15 Abril 2015 ABSTRACT Revisada: 13 Octubre 2015 We report an event of predation between two fossorial species; the snake Anilius scytale on Aceptada: 21 Marzo 2016 the caecilian Oscaecilia bassleri, from the Manu Biosphere Reserve, southeast Peru. This is the Editor Asociado: A. Prudente first ever report of predation on O. bassleri and complements information known about the feeding ecology of A. scytale. Tropical fossorial herpetofauna species are rarely volunteer activities. The specimen was crossing one found due to their secretive lifestyles and therefore, of the pathways within the station, and was caught there is a paucity of information about their ecology and temporarily withheld in the project work area (Maritz and Alexander, 2009; Böhm et al., 2013), to be measured and photographed. At 21:30, during including feeding habits (Maschio et al., 2010). Here the measurements, the individual started to open we report upon a predation event involving two and close its mouth and began to regurgitate an fossorial species; the caecilian, Oscaecilia bassleri individual of O. bassleri (Fig. 1). (Dunn, 1942), predated by the coral pipe snake, The individual of A. scytale was 68.5 cm in Anilius scytale (Linnaeus, 1758). -

A NOVEL GAIN of FUNCTION of the <I>IRX1</I> and <I>IRX2</I> GENES DISRUPTS AXIS ELONGATION in the ARAUCA

Clemson University TigerPrints All Dissertations Dissertations 8-2013 A NOVEL GAIN OF FUNCTION OF THE IRX1 AND IRX2 GENES DISRUPTS AXIS ELONGATION IN THE ARAUCANA RUMPLESS CHICKEN Nowlan Freese Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations Part of the Developmental Biology Commons Recommended Citation Freese, Nowlan, "A NOVEL GAIN OF FUNCTION OF THE IRX1 AND IRX2 GENES DISRUPTS AXIS ELONGATION IN THE ARAUCANA RUMPLESS CHICKEN" (2013). All Dissertations. 1198. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations/1198 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A NOVEL GAIN OF FUNCTION OF THE IRX1 AND IRX2 GENES DISRUPTS AXIS ELONGATION IN THE ARAUCANA RUMPLESS CHICKEN A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Biological Sciences by Nowlan Hale Freese August 2013 Accepted by: Dr. Susan C. Chapman, Committee Chair Dr. Lesly A. Temesvari Dr. Matthew W. Turnbull Dr. Leigh Anne Clark Dr. Lisa J. Bain ABSTRACT Caudal dysplasia describes a range of developmental disorders that affect normal development of the lumbar spinal column, sacrum and pelvis. An important goal of the congenital malformation field is to identify the genetic mechanisms leading to caudal deformities. To identify the genetic cause(s) and subsequent molecular mechanisms I turned to an animal model, the rumpless Araucana chicken breed. Araucana fail to form vertebrae beyond the level of the hips. -

Snake Skeletonizing Manual

Snake Skeletonizing Manual By Ellen Kuo Illustrations by Omar Malik, Juliana Olsson, and Sara Brenner © 2020 Museum of Vertebrate Zoology Table of Contents Snake anatomy reference images …………………………………………………. Page 2-3 Station setup …………………………………………………. Page 4 Initial data collection and setup …………………………………………………. Page 5-8 Taking photos …………………………………………………. Page 9 Initially determining the sex ………………………………………………… Page 9-10 Skinning …………………………………………………. Page 11-12 Opening and sexing …………………………………………………. Page 13-24 Examples of male gonads …………………………………………………. Page 14-16 Examples of female gonads …………………………………………………... Page 17-23 Taking tissues …………………………………………………. Page 25 Stomach contents, parasites …………………………………………………. Page 25 Finishing and cleaning up …………………………………………………. Page 26 1 Snake Anatomy References 2 Illustration by Sara Brenner Snake skeleton – note that the ribs go down the whole length of the body (they end at the vent, and then the tail does not have ribs). Illustration by Sara Brenner Most snake skulls consist of many small, delicate bones that are unfused. The lower jaw is not fused at the center, allowing the snake to use its lower jaws like arms to slowly feed in prey. Snakes have very sharp, delicate teeth, and lots, and lots, and lots of them — typically on several different jaw bones! Avoid disturbing the teeth. 3 Station Setup Materials ● Snake ● Original data ● Skeleton tag ● Gloves ● Worksheet ● Micron pen ● Forceps ● Scissors (large and small) ● Tray (optional) ● Camera* ● Ruler and/or measuring tape ● Tissue vial ● Vial pen* ● MVZ barcode (for tissue vial) ● Paper towel labeled with H, L, M, K ● Prep Lab Catalog* ● Extra paper towels (optional) ● Scale* ● Herp field guide (for local animals)* ● Probe ● Biohazard bin* *shared materials with the rest of the class 4 Before you start cutting ● Set up your station with all of the listed materials (or access to them) ● Identify the genus and species of your specimen, double checking with the class coordinator to make sure it is correct. -

THE ORIGIN and EVOLUTION of SNAKE EYES Dissertation

CONQUERING THE COLD SHUDDER: THE ORIGIN AND EVOLUTION OF SNAKE EYES Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment for the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Christopher L. Caprette, B.S., M.S. **** The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Thomas E. Hetherington, Advisor Approved by Jerry F. Downhower David L. Stetson Advisor The graduate program in Evolution, John W. Wenzel Ecology, and Organismal Biology ABSTRACT I investigated the ecological origin and diversity of snakes by examining one complex structure, the eye. First, using light and transmission electron microscopy, I contrasted the anatomy of the eyes of diurnal northern pine snakes and nocturnal brown treesnakes. While brown treesnakes have eyes of similar size for their snout-vent length as northern pine snakes, their lenses are an average of 27% larger (Mann-Whitney U test, p = 0.042). Based upon the differences in the size and position of the lens relative to the retina in these two species, I estimate that the image projected will be smaller and brighter for brown treesnakes. Northern pine snakes have a simplex, all-cone retina, in keeping with a primarily diurnal animal, while brown treesnake retinas have mostly rods with a few, scattered cones. I found microdroplets in the cone ellipsoids of northern pine snakes. In pine snakes, these droplets act as light guides. I also found microdroplets in brown treesnake rods, although these were less densely distributed and their function is unknown. Based upon the density of photoreceptors and neural layers in their retinas, and the predicted image size, brown treesnakes probably have the same visual acuity under nocturnal conditions that northern pine snakes experience under diurnal conditions. -

The History and Influence of Maria Sibylla Merian's Bird-Eating Tarantula: Circulating Images and the Production of Natural Knowledge

Biology Faculty Publications Biology 2016 The History and Influence of Maria Sibylla Merian's Bird-Eating Tarantula: Circulating Images and the Production of Natural Knowledge Kay Etheridge Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/biofac Part of the Biology Commons, and the Illustration Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Recommended Citation Etheridge, K. "The History and Influence of Maria Sibylla Merian’s Bird-Eating Tarantula: Circulating Images and the Production of Natural Knowledge." Global Scientific Practice in the Age of Revolutions, 1750 – 1850. P. Manning and D. Rood, eds. (Pittsburgh, University of Pittsburgh Press. 2016). 54-70. This is the publisher's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/biofac/54 This open access book chapter is brought to you by The Cupola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The Cupola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The History and Influence of Maria Sibylla Merian's Bird-Eating Tarantula: Circulating Images and the Production of Natural Knowledge Abstract Chapter Summary: A 2009 exhibition at the Fitzwilliam Museum on the confluence of science and the visual arts included a plate from a nineteenth-century encyclopedia owned by Charles Darwin showing a tarantula poised over a dead bird (figure 3.1).1 The genesis of this startling scene was a work by Maria Sibylla Merian (German, 1647–1717), and the history of this image says much about how knowledge of the New World was obtained, and how it was transmitted to the studies and private libraries of Europe, and from there into popular works like Darwin’s encyclopedia. -

The Mediaeval Bestiary and Its Textual Tradition

THE MEDIAEVAL BESTIARY AND ITS TEXTUAL TRADITION Volume 1: Text Patricia Stewart A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2012 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/3628 This item is protected by original copyright The Mediaeval Bestiary and its Textual Tradition Patricia Stewart This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 17th August, 2012 1. Candidate’s declarations: I, Patricia Stewart, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 88 000 words in length, has been written by me, that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student in September, 2007 and as a candidate for the degree of PhD in May, 2008; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2007 and 2012. Date 17th August, 2012 signature of candidate ……… 2. Supervisor’s declaration: I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of PhD in the University of St Andrews and that the candidate is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. Date 17th August, 2012 signature of supervisor ……… 3. Permission for electronic publication: (to be signed by both candidate and supervisor) In submitting this thesis to the University of St Andrews I understand that I am giving permission for it to be made available for use in accordance with the regulations of the University Library for the time being in force, subject to any copyright vested in the work not being affected thereby. -

Kansas Herpetological Society Newsletter No. 54 December, 1983

KANSAS HERPETOLOGICAL SOCIETY NEWSLETTER NO. 54 DECEMBER, 1983 1984 KHS DUES DUE, DO ... In this issue of the KHS Newsletter, you should find the nifty return-by-mail envelope for payment of your 1984 Kansas Herpetological Society dues. Since your dues are what finances this newsletter, prompt payment is appreciated. If you have already paid your 1984 dues, pass the envelope on to a friend who would like to JO~n the Kansas Herpetological Society. Of all the Regional Herpetological Societies in the U.S . , the KHS has some of the LO\fEST membership rates. If you are missing your dues envelope, or have lost it, the rates are still as follows: Regular member (U.S . ) $4.00 Non-U .S. member $8.00 Contributing member $15.00 Make your checks or money orders payable to KHS. Be sure that your CORRECT mailing address is printed neatly on the outside of the envelope. Send your money to: Kansas Herpetological Society Museum of Natural History University of Kansas Lawrence, Kansas 66045 KHS NEWSLETTER NO. 54 1 ANNOUNCENENTS Who Are Those Herpetologists, Anyway? If you are in the mood to expand your Christmas card list, here is a chance to get the names and addresses of over 2,000 professional and amateur herpetologists, plus lots of other neat stuff. The Silver Anniversary Membership Directory of the Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles has just been published and also contains a list of herpetological societies and organizations of the world (organized by country, each listing includes an address to write to and usually a list of publications) , a brief history of the SSAR, and other useful information about the SSAR and its organization. -

Herpetological Natural History Vol.6 December 1998 No.2

HERPETOLOGICAL NATURAL HISTORY VOL.6 DECEMBER 1998 NO.2 Herpetological Natural History, 6(2), 1998, pages 78-150. ©1998 by the International Herpetological Symposium, Inc. NATURAL HISTORY OF SNAKES IN FORESTS OF THE MANAUS REGION, CENTRAL AMAZONIA, BRAZIL* Marcio Martins Departamento de Ecologia Geral, Instituto de Biociencias, Universidade de Sao Paulo, Caixa Postal 11.461, 05422-970 Sao Paulo SP, Brazil M. Ermelinda Oliveira Departamento de Parasitologia, Instituto de Ciencias Biol6gicas, Universidade do Amazonas, Av. Rodrigo Otavio 3.000, 69077-000 Manaus AM, Brazil Abstract. We present natural history information on 66 species of snakes found in the forests of the Mana us region, Central Amazonia, Brazil. For each species, we provide information on size, color pattern, habitat and microhabitat, feeding habits, reproduction, and defense. We also include a partial summary of the infor mation available in the literature for Amazonian localities. Our results are based on nearly 800 captures or sightings of snakes made from 1990-95 at localities around Manaus, mostly at a primary forest reserve 25 km north of Manaus. Field data at this reserve were obtained during over 2600 person-h of visually search ing for snakes, ca. 1600 of which occurred during time-constrained search. Temperature and relative humid ity in Manaus are high and the amount of annual rainfall (2075 mm/yr) is relatively small, with a long dry season (4-7 mo). Of the 65 species for which information is available, 28 (42%) are primarily terrestrial, 20 (30%) fossorial and/or cryptozoic, 13 (20%) arboreal, and four (6%) aquatic, although many species use more than one microhabitat when active. -

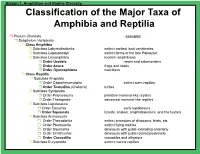

Classification of the Major Taxa of Amphibia and Reptilia

Station 1. Amphibian and Reptile Diversity Classification of the Major Taxa of Amphibia and Reptilia ! Phylum Chordata examples ! Subphylum Vertebrata ! Class Amphibia ! Subclass Labyrinthodontia extinct earliest land vertebrates ! Subclass Lepospondyli extinct forms of the late Paleozoic ! Subclass Lissamphibia modern amphibians ! Order Urodela newts and salamanders ! Order Anura frogs and toads ! Order Gymnophiona caecilians ! Class Reptilia ! Subclass Anapsida ! Order Captorhinomorpha extinct stem reptiles ! Order Testudina (Chelonia) turtles ! Subclass Synapsida ! Order Pelycosauria primitive mammal-like reptiles ! Order Therapsida advanced mammal-like reptiles ! Subclass Lepidosaura ! Order Eosuchia early lepidosaurs ! Order Squamata lizards, snakes, amphisbaenians, and the tuatara ! Subclass Archosauria ! Order Thecodontia extinct ancestors of dinosaurs, birds, etc ! Order Pterosauria extinct flying reptiles ! Order Saurischia dinosaurs with pubis extending anteriorly ! Order Ornithischia dinosaurs with pubis rotated posteriorly ! Order Crocodilia crocodiles and alligators ! Subclass Euryapsida extinct marine reptiles Station 1. Amphibian Skin AMPHIBIAN SKIN Most amphibians (amphi = double, bios = life) have a complex life history that often includes aquatic and terrestrial forms. All amphibians have bare skin - lacking scales, feathers, or hair -that is used for exchange of water, ions and gases. Both water and gases pass readily through amphibian skin. Cutaneous respiration depends on moisture, so most frogs and salamanders are