Innamincka Talk a Grammar of the Innamincka Dialect of Yandruwandha with Notes on Other Dialects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction

This item is Chapter 1 of Language, land & song: Studies in honour of Luise Hercus Editors: Peter K. Austin, Harold Koch & Jane Simpson ISBN 978-0-728-60406-3 http://www.elpublishing.org/book/language-land-and-song Introduction Harold Koch, Peter Austin and Jane Simpson Cite this item: Harold Koch, Peter Austin and Jane Simpson (2016). Introduction. In Language, land & song: Studies in honour of Luise Hercus, edited by Peter K. Austin, Harold Koch & Jane Simpson. London: EL Publishing. pp. 1-22 Link to this item: http://www.elpublishing.org/PID/2001 __________________________________________________ This electronic version first published: March 2017 © 2016 Harold Koch, Peter Austin and Jane Simpson ______________________________________________________ EL Publishing Open access, peer-reviewed electronic and print journals, multimedia, and monographs on documentation and support of endangered languages, including theory and practice of language documentation, language description, sociolinguistics, language policy, and language revitalisation. For more EL Publishing items, see http://www.elpublishing.org 1 Introduction Harold Koch,1 Peter K. Austin 2 & Jane Simpson 1 Australian National University1 & SOAS University of London 2 1. Introduction Language, land and song are closely entwined for most pre-industrial societies, whether the fishing and farming economies of Homeric Greece, or the raiding, mercenary and farming economies of the Norse, or the hunter- gatherer economies of Australia. Documenting a language is now seen as incomplete unless documenting place, story and song forms part of it. This book presents language documentation in its broadest sense in the Australian context, also giving a view of the documentation of Australian Aboriginal languages over time.1 In doing so, we celebrate the achievements of a pioneer in this field, Luise Hercus, who has documented languages, land, song and story in Australia over more than fifty years. -

Management Plan for the South Australian Lake Eyre Basin Fisheries

MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR THE SOUTH AUSTRALIAN LAKE EYRE BASIN FISHERIES Part 1 – Commercial and recreational fisheries Part 2 – Yandruwandha Yawarrawarrka Aboriginal traditional fishery Approved by the Minister for Agriculture, Food and Fisheries pursuant to section 44 of the Fisheries Management Act 2007. Hon Gail Gago MLC Minister for Agriculture, Food and Fisheries 1 March 2013 Page 1 of 118 PIRSA Fisheries & Aquaculture (A Division of Primary Industries and Regions South Australia) GPO Box 1625 ADELAIDE SA 5001 www.pir.sa.gov.au/fisheries Tel: (08) 8226 0900 Fax: (08) 8226 0434 © Primary Industries and Regions South Australia 2013 Disclaimer: This management plan has been prepared pursuant to the Fisheries Management Act 2007 (South Australia) for the purpose of the administration of that Act. The Department of Primary Industries and Regions SA (and the Government of South Australia) make no representation, express or implied, as to the accuracy or completeness of the information contained in this management plan or as to the suitability of that information for any particular purpose. Use of or reliance upon information contained in this management plan is at the sole risk of the user in all things and the Department of Primary Industries and Regions SA (and the Government of South Australia) disclaim any responsibility for that use or reliance and any liability to the user. Copyright Notice: This work is copyright. Copyright in this work is owned by the Government of South Australia. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 (Commonwealth), no part of this work may be reproduced by any process without written permission of the Government of South Australia. -

Heritage of the Birdsville and Strzelecki Tracks

Department for Environment and Heritage Heritage of the Birdsville and Strzelecki Tracks Part of the Far North & Far West Region (Region 13) Historical Research Pty Ltd Adelaide in association with Austral Archaeology Pty Ltd Lyn Leader-Elliott Iris Iwanicki December 2002 Frontispiece Woolshed, Cordillo Downs Station (SHP:009) The Birdsville & Strzelecki Tracks Heritage Survey was financed by the South Australian Government (through the State Heritage Fund) and the Commonwealth of Australia (through the Australian Heritage Commission). It was carried out by heritage consultants Historical Research Pty Ltd, in association with Austral Archaeology Pty Ltd, Lyn Leader-Elliott and Iris Iwanicki between April 2001 and December 2002. The views expressed in this publication are not necessarily those of the South Australian Government or the Commonwealth of Australia and they do not accept responsibility for any advice or information in relation to this material. All recommendations are the opinions of the heritage consultants Historical Research Pty Ltd (or their subconsultants) and may not necessarily be acted upon by the State Heritage Authority or the Australian Heritage Commission. Information presented in this document may be copied for non-commercial purposes including for personal or educational uses. Reproduction for purposes other than those given above requires written permission from the South Australian Government or the Commonwealth of Australia. Requests and enquiries should be addressed to either the Manager, Heritage Branch, Department for Environment and Heritage, GPO Box 1047, Adelaide, SA, 5001, or email [email protected], or the Manager, Copyright Services, Info Access, GPO Box 1920, Canberra, ACT, 2601, or email [email protected]. -

A Review of Lake Frome & Strzelecki Regional Reserves 1991-2001

A Review of Lake Frome and Strzelecki Regional Reserves 1991 – 2001 s & ark W P il l d a l i f n e o i t a N South Australia A Review of Lake Frome and Strzelecki Regional Reserves 1991 – 2001 Strzelecki Regional Reserves Lake Frome This review has been prepared and adopted in pursuance to section 34A of the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972. Published by the Department for Environment and Heritage Adelaide, South Australia July 2002 © Department for Environment and Heritage ISBN: 0 7590 1038 2 Prepared by Outback Region National Parks & Wildlife SA Department for Environment and Heritage Front cover photographs: Lake Frome coastline, Lake Frome Regional Reserve, supplied by R Playfair and reproduced with permission. Montecollina Bore, Strzelecki Regional Reserve, supplied by C. Crafter and reproduced with permission. Department for Environment and Heritage TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ................................................................................................................................................iii LIST OF TABLES..................................................................................................................................................iii LIST OF ACRONYMS and ABBREVIATIONS...................................................................................................iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ......................................................................................................................................iv FOREWORD .......................................................................................................................................................... -

Grs 513/11/P

GPO Box 464 Adelaide SA 5001 Tel (+61 8) 8204 8791 Fax (+61 8) 8260 6133 DX:336 [email protected] www.archives.sa.gov.au Special List GRS 513 Lodged company documents of defunct companies Series These files contain documents lodged by companies in Description accordance with the varying Companies Acts. Company files may contain some or all of the following lodged documents: Memorandum of Agreement, Articles of Association, Certificate of Incorporation, lists of shareholders, lists of directors, special resolutions ie. issues of shares, underwriting agreements and annual returns. Note: The term 'defunct' should not be understood to refer to the company. In this context it refers to the file being defunct, although given the age of the records some of the companies will have become defunct. Series date range 1844 - 1986 Agency State Records of South Australia responsible Access Open. Determination Contents 1874 – 1935 1 June 2016 GRS 513/11/P DEFUNCT COMPANIES FILES 4/1S74 The Stonyfell Olive Company Limited (Scm) \ 4/1874 The Stonyfell Olive Co. Limited (1 file) 1/1875 The East End Market Company (16cm)) 1/1S75 The East End Market Coy. Ltd. (1 file) 3/1SSO The Executor Trust & Agency Company of South Australia Limited (9cm &9cm)(2 bundles)) 10/1S7S Adelaide Underwriters Association Limited (3cm) 10/1S7S Marine Underwriters Association of South Australia Limited (1 file) 20/1SS2 Elder's Wool and Produce Company Limited (Scm) 4/1SS2 Northern Territory Laud Company Limited (4cm) 3/1SSO Executor Trustee & Agency Company of South Australia (Scm) 3/1SSO Executor Trustee & Agency Company of South Australia Limited (1 file) 7/1SS2 Northern Territory Land Company (1 file) 20/1SS2 Elder Smith & Co. -

FLOOD WARNING SYSTEM for the COOPER CREEK CATCHMENT

Bureau Home > Australia > Queensland > Rainfall & River Conditions > River Brochures > Thomson, Barcoo and Cooper FLOOD WARNING SYSTEM for the COOPER CREEK CATCHMENT This brochure describes the flood warning system operated by the Australian Government, Bureau of Meteorology for the Thomson, Barcoo Rivers and Cooper Creek. It includes reference information which will be useful for understanding Flood Warnings and River Height Bulletins issued by the Bureau's Flood Warning Centre during periods of high rainfall and flooding. Contained in this document is information about: (Last updated September 2019) Flood Risk Previous Flooding Flood Forecasting Local Information Flood Warnings and Bulletins Interpreting Flood Warnings and River Height Bulletins Flood Classifications Other Links Cooper Creek at Nappa Merrie Flood Risk The Thomson-Barcoo-Cooper catchment drains an area of approximately 237,000 square kilometres and is the largest river basin in Queensland. The catchment falls within the Lake Eyre basin, the largest and only co- ordinated internal drainage system in Australia with no external outlet, and which covers over 1.1 million square kilometres of central Australia. Floodwaters reach Lake Eyre after major flood events in the Cooper. The two main tributaries, the Thomson and Barcoo Rivers, merge into the Cooper Creek approximately 40 kilometres upstream of Windorah. The Thomson River and its tributaries flow in a general southerly direction and has several of the larger towns of the region including Longreach and Muttaburra along its banks. The Barcoo River flows in a general westerly direction and has major centres such as Isisford, Blackall, Barcaldine, Jericho and Tambo in its catchment. The Thomson-Barcoo-Cooper basin can be divided into two distinct areas: * Above Windorah, numerous well-defined creeks and channels flow into the Thomson and Barcoo. -

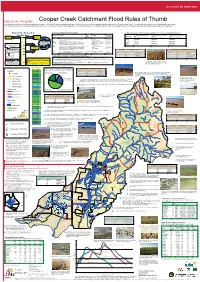

Cooper Creek Catchment Flood Rules of Thumb This Guide Has Used the Best Information Available at Present

QueenslandQueenslandthethe Smart Smart State State How to use this guide: Cooper Creek Catchment Flood Rules of Thumb This guide has used the best information available at present. It is intended to help you assess what type of flood is likely to occur in your area and indicate what amount of feed you might expect. You may wish to record your own flooding guides on the map. You can add more value to this guide by participating in an MLA EDGEnetwork Grazing Land Management (GLM) training package. GLM training helps you identify land types and flood zones and to develop a grazing management plan for your property Amount of rain needed Channel Country Flood descriptions Estimated Summer Flood Pasture Growth in the Channel Country Floodplains. Frequently flooded plains Occasionally flooded plains Swamps and depressions for flooding Flood type Description Land Hydrology Pasture growth Isolated Systems which supports: Flood type (C1) (C2) (C3) Widespread Widespread Rain 100 mm Localised Rain “HANDY” to flooded “GOOD” flood Then increases (kg DM/ha of useful feed) (kg DM/ha of useful feed) (kg DM/ha of useful feed) 95 “GOOD” flood Good Good floods are similar to handy floods, but cover a much higher C1, C3, C2 Flooded across most of 85 - 100% of to proportion of the floodplain (75% or more) and grow more feed per floodplains potential cattle Good 1200-2500 1500-3500 4500-8000 90 area than a handy flood. 80-100% inundation numbers 85 IF in 24-72 hrs Handy Handy floods occur when the water escapes from the gutters, C1, C3 Pushing out of gutters across 45 - 85% of Handy 750-1500 100-250 3500-6500 80 PRIOR, rains of (or useful) connecting up to form the large sheets of water. -

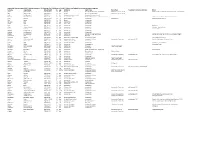

List of Deaths.Xlsx

Innamincka Records compiled 2011. Materials supplied b:- SA Genealogy Soc. D Spackman. K Buckley. Office for the Outback Community Authority, Pt Augusta. Surname Given Names Date of Death Sex Age Residence Death Place Burial Place Headstone Innamincka Cemetery Detail Burke Robert O'Hara 1861-06/07-? M 40y Victoria Near Burke Waterhole, Innamincka Melbourne General Cem Memorial Burke's Waterhole Cooper Creek Nr Innamincka Wills William John 1861-06/07-? M 27y Victoria Near Tilcha Waterhole Melbourne General Cem Colless Not Recorded 1880-08-17 F 3h Innamincka Coopers Creek Innamincka Coopers Creek Howard Henry Grenville 1881-11-01 M 50y Innamincka Station Between Mt Lyndhurst and Farina Town Cook. Injuries received thrown from his trap. Cook Richard 1883/4-12-02 M 45y Monta Collina Innamincka Patchewarra Police Mortuary Returns Tee James 1885-05-13 M 37y Farina Innamincka Richards John 1886-02-08 M 61y Innamincka Innamincka Budge John 1887-03-22 M 23y Oonta. Qld Innamincka Dick Samuel 1887-09-07 M 3w Innamincka Innamincka Bronchitis Rowe Thomas Roberts 1888-03-22 M 20y Innamincka Innamincka Labourer. Typhoid Fever. Copp Andrew 1888-05-10 M 37y Innamincka Innamincka Cancer of Throat Melville Not Recorded 1893-07-12 F 36h Innamincka Innamincka Melville Not Recorded 1893-07-12 F 24h Innamincka Innamincka Charley Not Recorded 1893-11-15 M 23y Innamincka Coopers Crk near Lake Hope Aboriginal. Drover.Verdict of Jury -no cause of death McDermott John 1891-07-12 M 36y Innamincka Adelaide Crossman William 1891-08-20 M 30y Nappa Merrie Station Qld Innamincka Station Police Mortuary Returns Bralla William Emanuel 1894-01-23 M 23y Innamincka Station Innamincka Station Innamincka Cemetery photograph 2011 Accidentally drowned Coopers Creek Hampton Edwin John 1894-12-28 M 23y Asbevale Station Qld Innamincka Smith Alick 1895-03-30 M 53y Innamincka Station Innamincka Stockman. -

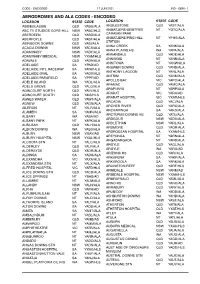

Aerodromes and Ala Codes

CODE - ENCODED 17 JUN 2021 IND - GEN - 1 AERODROMES AND ALA CODES - ENCODED LOCATION STATE CODE LOCATION STATE CODE ABBIEGLASSIE QLD YABG/ALA ANGLESTONE QLD YAST/ALA ABC TV STUDIOS GORE HILL NSW YABC/HLS ANMATJERE/GEMTREE NT YGTC/ALA ABERDEEN QLD YABD/ALA CARAVAN PARK ABERFOYLE QLD YABF/ALA ANMATJERE/PINE HILL NT YPHS/ALA STATION ABINGDON DOWNS QLD YABI/ALA ANNA CREEK SA YANK/ALA ACACIA DOWNS NSW YACS/ALA ANNA PLAINS HS WA YAPA/ALA ADAMINABY NSW YADY/ALA ANNANDALE QLD YADE/ALA ADAMINABY MEDICAL NSW YXAM/HLS ANNINGIE NT YANN/ALA ADAVALE QLD YADA/ALA ANNITOWA NT YANW/ALA ADELAIDE SA YPAD/AD ANSWER DOWNS QLD YAND/ALA ADELAIDE INTL RACEWAY SA YAIW/HLS ANTHONY LAGOON NT YANL/ALA ADELAIDE OVAL SA YAOV/HLS ANTRIM QLD YANM/ALA ADELAIDE/PARAFIELD SA YPPF/AD APOLLO BAY VIC YAPO/ALA ADELE ISLAND WA YADL/ALA ARAMAC QLD YAMC/ALA ADELS GROVE QLD YALG/ALA ARAPUNYA NT YARP/ALA AGINCOURT NORTH QLD YAIN/HLS ARARAT VIC YARA/AD AGINCOURT SOUTH QLD YAIS/HLS ARARAT HOSPITAL VIC YXAR/HLS AGNES WATER QLD YAWT/ALA ARCADIA QLD YACI/ALA AGNEW QLD YAGN/ALA ARCHER RIVER QLD YARC/ALA AILERON NT YALR/ALA ARCKARINGA SA YAKG/ALA ALAMEIN SA YAMN/ALA ARCTURUS DOWNS HS QLD YATU/ALA ALBANY WA YABA/AD ARDGOUR NSW YADU/ALA ALBANY PARK NT YAPK/ALA ARDLETHAN NSW YARL/ALA ALBILBAH QLD YALH/ALA ARDMORE QLD YAOR/ALA ALBION DOWNS WA YABS/ALA ARDROSSAN HOSPITAL SA YXAN/HLS ALBURY NSW YMAY/AD AREYONGA NT YARN/ALA ALBURY HOSPITAL NSW YXAL/HLS ARGADARGADA NT YARD/ALA ALCOOTA STN NT YALC/ALA ARGYLE QLD YAGL/ALA ALDERLEY QLD YALY/ALA ARGYLE WA YARG/AD ALDERSYDE QLD YADR/ALA ARIZONA HS -

Annual Report 2007–2008

07 08 NATIONAL NATIVE TITLE TRIBUNAL CONTACT DETAILS Annual Report 2007–2008 Tribunal National Native Title PRINCIPAL REGISTRY (PERTH) NEW SOUTH WALES AND AUSTRALIAN Level 4, Commonwealth Law Courts Building CAPITAL TERRITORY 1 Victoria Avenue Level 25 Perth WA 6000 25 Bligh Street Sydney NSW 2000 GPO Box 9973, Perth WA 6848 GPO Box 9973, Sydney NSW 2001 Telephone: (08) 9268 7272 Facsimile: (08) 9268 7299 Telephone: (02) 9235 6300 Facsimile: (02) 9233 5613 VICTORIA AND TASMANIA Level 8 SOUTH AUSTRALIA 310 King Street Level 10, Chesser House Annual Report Melbourne Vic. 3000 91 Grenfell Street Adelaide SA 5000 GPO Box 9973, Melbourne Vic. 3001 GPO Box 9973, Adelaide SA 5001 Telephone: (03) 9920 3000 2007–2008 Facsimile: (03) 9606 0680 Telephone: (08) 8306 1230 Facsimile: (08) 8224 0939 NORTHERN TERRITORY Level 5, NT House WESTERN AUSTRALIA 22 Mitchell Street Level 11, East Point Plaza Darwin NT 0800 233 Adelaide Terrace Perth WA 6000 GPO Box 9973, Darwin NT 0801 GPO Box 9973, Perth WA 6848 Telephone: (08) 8936 1600 Facsimile: (08) 8981 7982 Telephone: (08) 9268 9700 Facsimile: (08) 9221 7158 QUEENSLAND Level 30, 239 George Street NATIONAL FREECALL NUMBER: 1800 640 501 Brisbane Qld 4000 WEBSITE: www.nntt.gov.au GPO Box 9973, Brisbane Qld 4001 National Native Title Tribunal office hours: Telephone: (07) 3226 8200 8.30am – 5.00pm Facsimile: (07) 3226 8235 8.00am – 4.30pm (Northern Territory) CAIRNS (REGIONAL OFFICE) Level 14, Cairns Corporate Tower 15 Lake Street Cairns Qld 4870 PO Box 9973, Cairns Qld 4870 Telephone: (07) 4048 1500 Facsimile: (07) 4051 3660 Resolution of native title issues over land and waters. -

Kerwin 2006 01Thesis.Pdf (8.983Mb)

Aboriginal Dreaming Tracks or Trading Paths: The Common Ways Author Kerwin, Dale Wayne Published 2006 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School School of Arts, Media and Culture DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/1614 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/366276 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Aboriginal Dreaming Tracks or Trading Paths: The Common Ways Author: Dale Kerwin Dip.Ed. P.G.App.Sci/Mus. M.Phil.FMC Supervised by: Dr. Regina Ganter Dr. Fiona Paisley This dissertation was submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts at Griffith University. Date submitted: January 2006 The work in this study has never previously been submitted for a degree or diploma in any University and to the best of my knowledge and belief, this study contains no material previously published or written by another person except where due reference is made in the study itself. Signed Dated i Acknowledgements I dedicate this work to the memory of my Grandfather Charlie Leon, 20/06/1900– 1972 who took a group of Aboriginal dancers around the state of New South Wales in 1928 and donated half their gate takings to hospitals at each town they performed. Without the encouragement of the following people this thesis would not be possible. To Rosy Crisp, who fought her own battle with cancer and lost; she was my line manager while I was employed at (DATSIP) and was an inspiration to me. -

What's in a Name? a Typological and Phylogenetic

What’s in a Name? A Typological and Phylogenetic Analysis of the Names of Pama-Nyungan Languages Katherine Rosenberg Advisor: Claire Bowern Submitted to the faculty of the Department of Linguistics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts Yale University May 2018 Abstract The naming strategies used by Pama-Nyungan languages to refer to themselves show remarkably similar properties across the family. Names with similar mean- ings and constructions pop up across the family, even in languages that are not particularly closely related, such as Pitta Pitta and Mathi Mathi, which both feature reduplication, or Guwa and Kalaw Kawaw Ya which are both based on their respective words for ‘west.’ This variation within a closed set and similar- ity among related languages suggests the development of language names might be phylogenetic, as other aspects of historical linguistics have been shown to be; if this were the case, it would be possible to reconstruct the naming strategies used by the various ancestors of the Pama-Nyungan languages that are currently known. This is somewhat surprising, as names wouldn’t necessarily operate or develop in the same way as other aspects of language; this thesis seeks to de- termine whether it is indeed possible to analyze the names of Pama-Nyungan languages phylogenetically. In order to attempt such an analysis, however, it is necessary to have a principled classification system capable of capturing both the similarities and differences among various names. While people have noted some similarities and tendencies in Pama-Nyungan names before (McConvell 2006; Sutton 1979), no one has addressed this comprehensively.