Birds in the Amaxhosa World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 140 Bird Species Recorded in the Korsman Conservancy

The 140 Bird Species Recorded in the Korsman Conservancy Roberts 6 Scientific Name Probability Residence Season Alphabetical Name Full Name 294 Avocet, Pied Pied Avocet Recurvirostra avosetta 11% 1 All Year 464 Barbet, Black-collared Black-collared Barbet Lybius torquatus 56% 1 All Year 473 Barbet, Crested Crested Barbet Trachyphonus vaillantii 83% 1 All Year 824 Bishop, Southern Red Southern Red Bishop Euplectes orix 73% 1 All Year 826 Bishop, Yellow-crowned Yellow-crowned Bishop Euplectes afer 14% 1 All Year 78 Bittern, Little Little Bittern Ixobrychus minutus 7% 3.1 Dec-March 568 Bulbul, Dark-capped Dark-capped Bulbul Pycnonotus tricolor 86% 1 All Year 149 Buzzard, Common (Steppe ) Common (Steppe) Buzzard Buteo buteo 1% 3.1 Oct-Apr 130 Buzzard, European Honey European Honey Buzzard Pernis apivorus 3.1 Nov-Apr 870 Canary, Black-throated Black-throated Canary Crithagra atrogularis 11% 1 All Year 677 Cisticola, Levaillant’s Levaillant’s Cisticola Cisticola tinniens 36% 1 All Year 664 Cisticola, Zitting Zitting Cisticola Cisticola juncidis 13% 1 All Year 228 Coot, Red-knobbed Red-knobbed coot Fulica cristata 90% 1 All Year 58 Cormorant, Reed Reed Cormorant Phalacrocorax africanus 77% 1 All Year 55 Cormorant, White-breasted White-breasted Cormorant Phalacrocorax lucidus 62% 1 All Year 391 Coucal, Burchell’s Burchell’s Coucal Centropus burchellii 13% 1 All Year 213 Crake, Black Black Crake Amaurornis flavirostra 7% 1 All Year 548 Crow, Pied Pied crow Corvus albus 30% 1 All Year 386 Cuckoo, Diederik Diederik Cuckoo Chrysococcyx caprius 15% -

South Africa 3Rd to 22Nd September 2015 (20 Days)

Hollyhead & Savage Trip Report South Africa 3rd to 22nd September 2015 (20 days) Female Cheetah with cubs and Impala kill by Heinz Ortmann Trip Report compiled by Tour Leader: Heinz Ortmann Trip Report Hollyhead & Savage Private South Africa September 2015 2 Tour Summary A fantastic twenty day journey that began in the beautiful Overberg region and fynbos of the Western Cape, included the Wakkerstroom grasslands, coastal dune forest of iSimangaliso Wetland Park, the Baobab-studded hills of Mapungubwe National Park and ended along a stretch of road searching for Kalahari specials north of Pretoria amongst many others. We experienced a wide variety of habitats and incredible birds and mammals. An impressive 400-plus birds and close to 50 mammal species were found on this trip. This, combined with visiting little-known parts of South Africa such as Magoebaskloof and Mapungubwe National Park, made this tour special as well as one with many unforgettable experiences and memories for the participants. Our journey started out from Cape Town International Airport at around lunchtime on a glorious sunny early-spring day. Our journey for the first day took us eastwards through the Overberg region and onto the Agulhas plains where we spent the next two nights. The farmlands in these parts appear largely barren and consist of single crop fields and yet host a surprising number of special, localised and endemic species. Our afternoon’s travels through these parts allowed us views of several more common and widespread species such as Egyptian and Spur-winged Geese, raptors like Jackal Buzzard, Rock Kestrel and Yellow-billed Kite, Speckled Pigeons, Capped Wheatear, Pied Starling, the ever present Pied and Cape Crow, White-necked Raven and Pin-tailed Whydah, almost in full breeding plumage. -

Further Breeding Records for Birds (Aves) in Angola

Durban Natural Science Museum Novitates 36 ANGOLAN BIRD BREEDING RECORDS 1 FURTHER BREEDING RECORDS FOR BIRDS (AVES) IN ANGOLA W. RicHARD J. DeAn1*, URSULA FRAnKe2, GRAnT JOSePH1, FRANCIScO M. GOnÇALVeS3, MicHAeL S.L. MiLLS4,1, SUZAnne J. MiLTOn1, ARA MOnADJeM5 & H. DieTeR OScHADLeUS6 1DST/NRF Centre of Excellence at the Percy FitzPatrick Institute of African Ornithology, University of Cape Town, Rondebosch 7701, South Africa *Author for correspondence: [email protected] 2Tal 34, 80331 Munich, Germany 3ISCED, Department of Natural Sciences, Rua: Sarmento Rodrigues, P.O. Box 230, Lubango, Angola 4A.P. Leventis Ornithological Research Institute, University of Jos, P.O. Box 13404, Jos, Plateau State, Nigeria 5Department of Biological Sciences, University of Swaziland, Private Bag 4, Kwaluseni, Swaziland 6Animal Demography Unit, Department of Zoology, University of Cape Town, Rondebosch 7701, South Africa ean, W.R.J., Franke, U., Joseph, G., Gonçalves, F.M., Mills, M.S.L., Milton, S.J., Monadjem, A. D& Oschadleus, H.D. 2013. Further breeding records for birds (Aves) in Angola. Durban Natural Science Museum Novitates 36: 1-10. Some details of records of nests, eggs and nestlings of 167 (possibly 168) species in the bird collection at Lubango, Angola are given. This includes 23 species for which there were no Angolan breeding records at all, and one possibly new breeding species (Slaty Egret). The data also confirm the breeding of another 20 species strongly suspected of breeding in Angola, but that lacked egg or nestling records. KEYWORDS: Angola, birds, museum collections, breeding. INTRODUcTiOn SYSTeMATIC LiST One of the gaps in our knowledge of the natural history of birds in Taxonomy and order follows Gill & Donsker (2014). -

Disaggregation of Bird Families Listed on Cms Appendix Ii

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals 2nd Meeting of the Sessional Committee of the CMS Scientific Council (ScC-SC2) Bonn, Germany, 10 – 14 July 2017 UNEP/CMS/ScC-SC2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II (Prepared by the Appointed Councillors for Birds) Summary: The first meeting of the Sessional Committee of the Scientific Council identified the adoption of a new standard reference for avian taxonomy as an opportunity to disaggregate the higher-level taxa listed on Appendix II and to identify those that are considered to be migratory species and that have an unfavourable conservation status. The current paper presents an initial analysis of the higher-level disaggregation using the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World Volumes 1 and 2 taxonomy, and identifies the challenges in completing the analysis to identify all of the migratory species and the corresponding Range States. The document has been prepared by the COP Appointed Scientific Councilors for Birds. This is a supplementary paper to COP document UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.3 on Taxonomy and Nomenclature UNEP/CMS/ScC-Sc2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II 1. Through Resolution 11.19, the Conference of Parties adopted as the standard reference for bird taxonomy and nomenclature for Non-Passerine species the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World, Volume 1: Non-Passerines, by Josep del Hoyo and Nigel J. Collar (2014); 2. -

Phylogeography of Finches and Sparrows

In: Animal Genetics ISBN: 978-1-60741-844-3 Editor: Leopold J. Rechi © 2009 Nova Science Publishers, Inc. Chapter 1 PHYLOGEOGRAPHY OF FINCHES AND SPARROWS Antonio Arnaiz-Villena*, Pablo Gomez-Prieto and Valentin Ruiz-del-Valle Department of Immunology, University Complutense, The Madrid Regional Blood Center, Madrid, Spain. ABSTRACT Fringillidae finches form a subfamily of songbirds (Passeriformes), which are presently distributed around the world. This subfamily includes canaries, goldfinches, greenfinches, rosefinches, and grosbeaks, among others. Molecular phylogenies obtained with mitochondrial DNA sequences show that these groups of finches are put together, but with some polytomies that have apparently evolved or radiated in parallel. The time of appearance on Earth of all studied groups is suggested to start after Middle Miocene Epoch, around 10 million years ago. Greenfinches (genus Carduelis) may have originated at Eurasian desert margins coming from Rhodopechys obsoleta (dessert finch) or an extinct pale plumage ancestor; it later acquired green plumage suitable for the greenfinch ecological niche, i.e.: woods. Multicolored Eurasian goldfinch (Carduelis carduelis) has a genetic extant ancestor, the green-feathered Carduelis citrinella (citril finch); this was thought to be a canary on phonotypical bases, but it is now included within goldfinches by our molecular genetics phylograms. Speciation events between citril finch and Eurasian goldfinch are related with the Mediterranean Messinian salinity crisis (5 million years ago). Linurgus olivaceus (oriole finch) is presently thriving in Equatorial Africa and was included in a separate genus (Linurgus) by itself on phenotypical bases. Our phylograms demonstrate that it is and old canary. Proposed genus Acanthis does not exist. Twite and linnet form a separate radiation from redpolls. -

Host Specificity and Co-Speciation in Avian Haemosporidia in the Western Cape, South Africa

Wright State University CORE Scholar Biological Sciences Faculty Publications Biological Sciences 2-3-2014 Host Specificity And Co-Speciation In vianA Haemosporidia In The Western Cape, South Africa Sharon Okanga Graeme S. Cumming Philip A.R. Hockey Lisa Nupen Jeffrey L. Peters Wright State University - Main Campus, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/biology Part of the Biology Commons, and the Systems Biology Commons Repository Citation Okanga, S., Cumming, G. S., Hockey, P. A., Nupen, L., & Peters, J. L. (2014). Host Specificity And Co- Speciation In Avian Haemosporidia In The Western Cape, South Africa. PLoS One, 9 (2), e86382. https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/biology/664 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Biological Sciences at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Biological Sciences Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Host Specificity and Co-Speciation in Avian Haemosporidia in the Western Cape, South Africa Sharon Okanga1*, Graeme S. Cumming1, Philip A. R. Hockey1, Lisa Nupen1, Jeffrey L. Peters2 1 Percy FitzPatrick Institute, A Centre of Excellence for the Department of Science and Technology and National Research Foundation, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa, 2 Department of Biological Sciences, Wright State University, Dayton, Ohio, United States of America Abstract Host and pathogen ecology are often closely linked, with evolutionary processes often leading to the development of host specificity traits in some pathogens. Host specificity may range from ‘generalist’, where pathogens infect any available competent host; to ‘specialist’, where pathogens repeatedly infect specific host species or families. -

TNP SOK 2011 Internet

GARDEN ROUTE NATIONAL PARK : THE TSITSIKAMMA SANP ARKS SECTION STATE OF KNOWLEDGE Contributors: N. Hanekom 1, R.M. Randall 1, D. Bower, A. Riley 2 and N. Kruger 1 1 SANParks Scientific Services, Garden Route (Rondevlei Office), PO Box 176, Sedgefield, 6573 2 Knysna National Lakes Area, P.O. Box 314, Knysna, 6570 Most recent update: 10 May 2012 Disclaimer This report has been produced by SANParks to summarise information available on a specific conservation area. Production of the report, in either hard copy or electronic format, does not signify that: the referenced information necessarily reflect the views and policies of SANParks; the referenced information is either correct or accurate; SANParks retains copies of the referenced documents; SANParks will provide second parties with copies of the referenced documents. This standpoint has the premise that (i) reproduction of copywrited material is illegal, (ii) copying of unpublished reports and data produced by an external scientist without the author’s permission is unethical, and (iii) dissemination of unreviewed data or draft documentation is potentially misleading and hence illogical. This report should be cited as: Hanekom N., Randall R.M., Bower, D., Riley, A. & Kruger, N. 2012. Garden Route National Park: The Tsitsikamma Section – State of Knowledge. South African National Parks. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................................................2 2. ACCOUNT OF AREA........................................................................................................2 -

Laniarius Spp.) in Coastal Kenya and Somalia

Brian W. Finch et al. 74 Bull. B.O.C. 2016 136(2) Redefining the taxonomy of the all-black and pied boubous (Laniarius spp.) in coastal Kenya and Somalia by Brian W. Finch, Nigel D. Hunter, Inger Winkelmann, Karla Manzano-Vargas, Peter Njoroge, Jon Fjeldså & M. Thomas P. Gilbert Received 21 October 2015 Summary.—Following the rediscovery of a form of Laniarius on Manda Island, Kenya, which had been treated as a melanistic morph of Tropical Boubou Laniarius aethiopicus for some 70 years, a detailed field study strongly indicated that it was wrongly assigned. Molecular examination proved that it is the same species as L. (aethiopicus) erlangeri, until now considered a Somali endemic, and these populations should take the oldest available name L. nigerrimus. The overall classification of coastal boubous also proved to require revision, and this paper presents a preliminary new classification for taxa in this region using both genetic and morphological data. Genetic evidence revealed that the coastal ally of L. aethiopicus, recently considered specifically as L. sublacteus, comprises two unrelated forms, requiring a future detailed study. The black-and-white boubous—characteristic birds of Africa’s savanna and wooded regions—have been treated as subspecies of the highly polytypic Laniarius ferrugineus (Rand 1960), or subdivided, by separating Southern Boubou L. ferrugineus, Swamp Boubou L. bicolor and Turati’s Boubou L. turatii from the widespread and geographically variable Tropical Boubou L. aethiopicus (Hall & Moreau 1970, Fry et al. 2000, Harris & Franklin 2000). They are generally pied, with black upperparts, white or pale buff underparts, and in most populations a white wing-stripe. -

Onetouch 4.0 Scanned Documents

/ Chapter 2 THE FOSSIL RECORD OF BIRDS Storrs L. Olson Department of Vertebrate Zoology National Museum of Natural History Smithsonian Institution Washington, DC. I. Introduction 80 II. Archaeopteryx 85 III. Early Cretaceous Birds 87 IV. Hesperornithiformes 89 V. Ichthyornithiformes 91 VI. Other Mesozojc Birds 92 VII. Paleognathous Birds 96 A. The Problem of the Origins of Paleognathous Birds 96 B. The Fossil Record of Paleognathous Birds 104 VIII. The "Basal" Land Bird Assemblage 107 A. Opisthocomidae 109 B. Musophagidae 109 C. Cuculidae HO D. Falconidae HI E. Sagittariidae 112 F. Accipitridae 112 G. Pandionidae 114 H. Galliformes 114 1. Family Incertae Sedis Turnicidae 119 J. Columbiformes 119 K. Psittaciforines 120 L. Family Incertae Sedis Zygodactylidae 121 IX. The "Higher" Land Bird Assemblage 122 A. Coliiformes 124 B. Coraciiformes (Including Trogonidae and Galbulae) 124 C. Strigiformes 129 D. Caprimulgiformes 132 E. Apodiformes 134 F. Family Incertae Sedis Trochilidae 135 G. Order Incertae Sedis Bucerotiformes (Including Upupae) 136 H. Piciformes 138 I. Passeriformes 139 X. The Water Bird Assemblage 141 A. Gruiformes 142 B. Family Incertae Sedis Ardeidae 165 79 Avian Biology, Vol. Vlll ISBN 0-12-249408-3 80 STORES L. OLSON C. Family Incertae Sedis Podicipedidae 168 D. Charadriiformes 169 E. Anseriformes 186 F. Ciconiiformes 188 G. Pelecaniformes 192 H. Procellariiformes 208 I. Gaviiformes 212 J. Sphenisciformes 217 XI. Conclusion 217 References 218 I. Introduction Avian paleontology has long been a poor stepsister to its mammalian counterpart, a fact that may be attributed in some measure to an insufRcien- cy of qualified workers and to the absence in birds of heterodont teeth, on which the greater proportion of the fossil record of mammals is founded. -

Nesting Sites of the Cape Sparrow Passer Melanurus in Maloti/Drakensber, Southern Africa

Intern. Stud. Sparrows 2013, 37: 28-31 Grzegorz KOPIJ Department of Wildlife Management , University of Namibia, Katima Mulilo Campus, Private Bag 1096, Wenela Rd., Katima Mulilo, Namibia E-mail: [email protected] NESTING SITES OF THE CAPE SPARROW PASSER MELANURUS IN MALOTI/DRAKENSBER, SOUTHERN AFRICA ABSTRACT In Maloti/Drakensberg region, southern Africa, Cape Sparrow locates nests (N=108) mainly in trees (38.9%), shrubs (27.8%) and man-made structures (29.6%). Most oc- cupied trees were exotic (31.6%), while all (27.8%) occupied shrubs were indigenous. A few nests (3.8%) were found in disused weavers’ nests. Nesting sites ranged in height from 1.5 m to 10 m above the ground; on average – 4.2 m (N=52). Key words: nest sites, weavers, Lesotho INTRODUCTION The Cape SparrowPasser melanurus is a common species in southern Africa, occurring in arid savanna, woodlands, farmlands and human habitations. It is monogamous and territorial, breeding singly or in loose colonies. Up to 15 nests may be located in one tree. Nests are relatively large, placed 2-20 m above ground (Hockey et al. 2005). Cape Sparrow places their nests on shrubs and trees, both indigenous and exotic, and on various man-made structures (Hockey at al. 2005). A detailed analysis of nesting sites was hitherto made only in the city of Bloemfontein, South Africa, where most nests were placed in trees such as Celtis africana, Acacia karroo and Ulmus parvifolia (Kopij 1999). In this note, further contribution is made on this aspect of breeding ecology. It is expected that, the species will show different preferences for nesting sites, being highly dependent on man-made structures in basically treeless grasslands. -

South Africa : Cape to Kruger

South Africa : Cape to Kruger September 12 - 26, 2019 Greg Smith, with Dalton Gibbs & Nick Fordyce as local expert guides with 10 participants: Renata, Linda, Sandy, Liz, Terry, Rita & Mike, Laura & George, Rebecca & David List compiled by Greg Smith Summary: Our unspoken goal was to surpass last year’s species list in numbers – bringing even more magic to the trip than the three guides had viewed with 2018’s clients. And we accomplished this by finding 100 more bird species than last year! This success was due to weather, clients and past experience. Given that we were further south on the continent, there were still some migrants that hadn’t quite made it to the tip of Africa. We excelled on raptors with twenty-four species and with mammal numbers coming in at 51 species. We achieved great looks at Africa’s Big Five on two of our three days in Kruger National Park, which is a success given the status of the white rhinoceros. The weather cooperated both in the Western Cape where much needed sporadic rain happened mostly during the night time hours, and in the eastern part of the country where the summer rainy season waited until two days after our departure. The following list gives you an indication of just how rich South Africa is in diversity with wildlife and birds, but doesn’t even point to its world-renowned plant biomes. Take a read and enjoy what we experienced… BIRDS: 359 species recorded OSTRICHES: Struthionidae (1) Common Ostrich Struthio camelus— Our time in Kruger was where we saw most of the wild birds, not common though -

Namibia & the Okavango

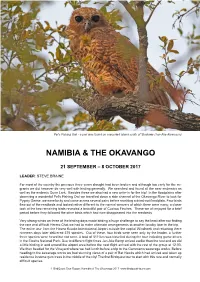

Pel’s Fishing Owl - a pair was found on a wooded island south of Shakawe (Jan-Ake Alvarsson) NAMIBIA & THE OKAVANGO 21 SEPTEMBER – 8 OCTOBER 2017 LEADER: STEVE BRAINE For most of the country the previous three years drought had been broken and although too early for the mi- grants we did however do very well with birding generally. We searched and found all the near endemics as well as the endemic Dune Lark. Besides these we also had a new write-in for the trip! In the floodplains after observing a wonderful Pel’s Fishing Owl we travelled down a side channel of the Okavango River to look for Pygmy Geese, we were lucky and came across several pairs before reaching a dried-out floodplain. Four birds flew out of the reedbeds and looked rather different to the normal weavers of which there were many, a closer look at the two remaining birds revealed a beautiful pair of Cuckoo Finches. These we all enjoyed for a brief period before they followed the other birds which had now disappeared into the reedbeds. Very strong winds on three of the birding days made birding a huge challenge to say the least after not finding the rare and difficult Herero Chat we had to make alternate arrangements at another locality later in the trip. The entire tour from the Hosea Kutako International Airport outside the capital Windhoek and returning there nineteen days later delivered 375 species. Out of these, four birds were seen only by the leader, a further three species were heard but not seen.