1 Beloit Poetry Journal Fall 2014 Bpjbeloit Poetry Journal Vol. 65

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Doña Ana County

Diven Ancient reaches game every lives on cornerco of Page A25 country PageP A12 $1.00 • © 2016 LAS CRUCES BULLETIN LOCAL NEWS AND ENTERTAINMENT SINCE 1969 • WWW.LASCRUCESBULLETIN.COM • FRIDAY,DAY, MARCH 4, 2016 VOLUME 48 • NUMBERN 50 District Pecan attorney’s conference offi ce partners to draw 600 By Darrell J. Pehr with Uber For the Bulletin With an update on the proposed pecan marketing Bulletin report order and the excitement of Doña Ana County District Attorney an “on” year for pecan pro- Mark D’Antonio announced a partner- duction, a big turnout is ex- ship with the ridesharing service Uber pected for the 50th annual to promote a safe alternative to drinking Western Pecan Growers As- and driving. sociation conference and As part of the partnership, Uber will trade show Sunday to Tues- offer new users a $15 credit and existing day, March 6 to 8 in Las users a chance to win $100 in free trans- Cruces at Hotel Encanto, portation. 705 S. Telshor Blvd. “We always make it a point to curb “We have a lot of interest drunk driving during the holidays but already,” said John White, it’s a year round problem, especially in director of the association. our state,” D’Antonio said. “We are expecting up to 600 New users can access the free ride people.” credit by downloading the Uber app and Registered conference at- entering the promo code DANTONIO. tendees will have access to Meanwhile, existing users can qualify to meals, a reception, the con- win $100 in free transportation by enter- ference and the equipment ing the promo code JUSTICEMAT- show. -

What We Can Learn About Strategies, Language Learning, and Life from Two Extreme Cases: the Role of Well-Being Theory

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching Department of English Studies, Faculty of Pedagogy and Fine Arts, Adam Mickiewicz University, Kalisz SSLLT 4 (4). 2014. 593-615 doi: 10.14746/ssllt.2014.4.4.2 http://www.ssllt.amu.edu.pl What we can learn about strategies, language learning, and life from two extreme cases: The role of well-being theory Rebecca L. Oxford Oxford Associates, Huntsville, AL, USA [email protected] Abstract This article presents two foreign or second language (L2) learner histories represent- ing the extreme ends of the spectrum of learner well-being. One story reflects the very positive learning experiences of a highly strategic learner, while the other story focuses on a less strategic learner’s negative, long-lasting responses to a single trau- matic episode. The theoretical framework comes from the concept of well-being in positive psychology (with significant adaptations). In addition to contrasting the two cases through the grounded theory approach, the study suggests that the adapted well-being framework is useful for understanding L2 learning experiences, even when the experiences are negative. Keywords: well-being theory, positive psychology, language learning experi- ences, positive and negative emotions, learner histories 1. Introduction Second or foreign language (L2) learners sometimes react in extremely different ways as they acquire a new language. This article presents two cases, one very positive (Mark) and the other very negative (Wanda), represented in personal 593 Rebecca L. Oxford histories written by the learners themselves. -

Lenten Meditations

Grand Rapids Choir of Men and Boys Lenten & Easter Meditations 29th Season 2019 Andrew Nethsingha Director of Music – St. John’s College Choir, Cambridge Our Lenten concert is all the more special this year by the choir’s fourth residency with Andrew Nethsingha, Director of Music of the Choir of St. John’s College, Cambridge. Andrew is truly one of the most skilled and inspiring choir trainers in the world today. Mr. Nethsingha began as a chorister at Exeter Cathedral where he sang for his father, Lucian Nethsingha. He later studied at the Royal College of Music where he won seven prizes, and at St. John’s College, Cambridge. He held Organ Scholarships under Christopher Robinson at St. George’s Chapel - Windsor Castle, and George Guest at St. John’s College, Cambridge. He next took up the position of Assistant Organist at Wells Cathedral where our Director of Music, Scott Bosscher, sang daily in the choir for Andrew for three years. Mr. Nethsingha was subsequently Director of Music at Truro and Gloucester Cathedrals, and Artistic Director of the Gloucester Three Choirs Festival. He has been the Music Director at St. John’s since 2007. Recent venues where Mr. Nethsingha has inspired both musicians & audiences alike include the Royal Albert Hall & Royal Festival Hall London, Konzerthaus Berlin, Müpa Budapest, Royal Concertgebouw Holland, Singapore Esplanade, Birmingham Symphony Hall and Hong Kong City Hall. We are blessed in west Michigan by Andrew including us in his music making itenery! The Choir of St. John’s College, Cambridge Andrew Nethsingha’s 2019 Grand Rapids residency has been graciously underwritten by Douglas & Barbara Kindschi May & June 2019 - 29th Anniversary Concluding Concerts The Basilica of St. -

02-2016 Index Good Short Total Song 1 42 0 42 SHAWN MENDES

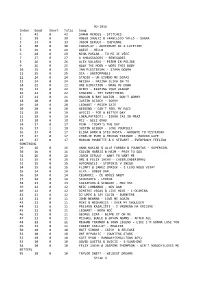

02-2016 Index Good Short Total Song 1 42 0 42 SHAWN MENDES - STITCHES 2 38 0 38 ROBIN SHULTZ & FRANCESCO YATES - SUGAR 3 33 0 33 JASON DERULO - CHEYENNE 4 30 0 30 COLDPLAY - ADVENTURE OF A LIFETIME 5 29 0 29 ADELE - HELLO 6 28 0 28 NINA PUŠLAR - TO MI JE VŠEČ 7 27 0 27 X AMBASSADORS - RENEGADES 8 26 0 26 ALEX VOLASKO - PESEM IN POLJUB 9 26 0 26 WALK THE MOON - WORK THIS BODY 10 25 0 25 JAN PLESTENJAK - STARA DOBRA 11 25 0 25 SIA - UNSTOPPABLE 12 24 0 24 STADIO - UN GIORNO MI DIRAI 13 24 0 24 NEISHA - NAJINA SLIKA IN TI 14 22 0 22 ONE DIRECTION - DRAG ME DOWN 15 22 0 22 BIRDY - KEEPING YOUR HEADUP 16 22 0 22 SHAKIRA - TRY EVERYTHING 17 21 0 21 MADCON & RAY DALTON - DON'T WORRY 18 20 0 20 JUSTIN BIEBER - SORRY 19 20 0 20 LEONART - POJEM ZATE 20 20 0 20 WEEKEND - CAN'T FEEL MY FACE 21 19 0 19 AVICII - FOR A BETTER DAY 22 18 0 18 LOKALPATRIOTI - ISKRA ČAS IN MRAZ 23 18 0 18 MI2 - BELI GRAD 24 17 0 17 PINK - TODAY'S THE DAY 25 17 1 18 JUSTIN BIEBER - LOVE YOURSELF 26 17 0 17 ELINA BORN & STIG RASTA - GOODBYE TO YESTERDAY 27 17 0 17 CHARLIE PUTH & MEGHAN TRAINOR - MARVIN GAYE 28 17 0 17 MARLON ROUDETTE & K STEWART - EVERYBODY FEELING SOMETHING 29 16 0 16 ANNA NAKLAB & ALLE FARBEN & YOUNOTUS - SUPERGIRL 30 16 0 16 CALVIN HARRIS & HAIM - PRAY TO GOD 31 16 0 16 JASON DERULO - WANT TO WANT ME 32 15 0 15 OMI & FELIX JAEHN - CHEERLEADER(RMX) 33 15 0 15 AVTOMOBILI - STOPINJE V SNEGU 34 15 0 15 FLIRRT & JANEZ ZMAZEK - Z LEVO NOGO VSTAT 35 14 0 14 ALYA - DOBER DAN 36 14 0 14 ČEDAHUČI - ČE HOČEŠ GREM 37 14 0 14 SIDDHARTA - LEDENA 38 13 0 13 CAZZAFURA -

JACKSON, HOPE W., Ph.D. Stones of Memory: Narratives from a Black Beach Community. (2013) Directed by Drs

JACKSON, HOPE W., Ph.D. Stones of Memory: Narratives from a Black Beach Community. (2013) Directed by Drs. Kathleen Casey and H. Svi Shapiro. 218 pp. In North Carolina, beaches have been considered “white” territory. These spaces are beautiful, natural landscapes that can provide healing and restoration for many. Yet, when black people enter this space, the dominant (white) culture is somehow surprised. This phenomenon is central to my research which focuses on a black beach community that (re)presents leisure spaces as sites of resistance. My research study centers on the stories told by the residents of a black beach community, Ocean City, North Carolina. I spent my summers here as a child. This small community encompasses a one-mile portion of Topsail Island, North Carolina. It was founded in 1949 in the midst of the segregated South. And, these narratives present the stones of living under these conditions. In my dissertation I interpret stones metaphorically like the biblical stones of the Israelites. While these stones are each unique, they still represent a living tradition for the individual as well as the collective group because the stones are the stories of living memories. They demonstrate the rich, cultural education that took place within the black community. Their stories reveal how black communities like Ocean City, taught black folks how such spaces were essential to surviving in a dominant (white) society. This study uses narrative theory in order to present the voices of black folks who are the descendants of kidnapped Africans. This study reveals their voices not only through the African tradition of storytelling, but also acknowledging the cultural literacy of black folks as valued by one another through a sense of community. -

ALL-2016 \226 Bele\236Nica

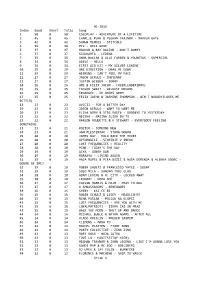

ALL-2016 Index Good Short Total Song 1 274 0 274 X AMBASSADORS - RENEGADES 2 253 0 253 LUKAS GRAHAM - 7 YEARS 3 220 0 220 JASON DERULO - CHEYENNE 4 214 0 214 RED HOT CHILI PEPPERS - DARK NECESSITIES 5 206 0 206 ROBIN SHULTZ & FRANCESCO YATES - SUGAR 6 202 0 202 DNCE - CAKE BY THE OCEAN 7 198 0 198 ANIKA HORVAT - NOČEM BIT SAMA 8 193 0 193 LEONART - POJEM ZATE 9 183 0 183 SHAWN MENDES - STITCHES 10 181 0 181 MADCON & RAY DALTON - DON'T WORRY 11 179 0 179 ANNA NAKLAB & ALLE FARBEN & YOUNOTUS - SUPERGIRL 12 178 0 178 MARLON ROUDETTE & K STEWART - EVERYBODY FEELING SOMETHING 13 171 0 171 ALEX VOLASKO - PESEM IN POLJUB 14 170 0 170 ČEDAHUČI - ČE HOČEŠ GREM 15 170 1 171 MARY ROSE - RESNIČEN SVET 16 168 0 168 SIDDHARTA - LEDENA 17 165 0 165 MI2 - BELI GRAD 18 164 0 164 PANDA - NORO 19 163 0 163 CHARLIE PUTH & MEGHAN TRAINOR - MARVIN GAYE 20 158 0 158 ONE REPUBLIC - WHEREVER I GO 21 158 1 159 GWEN STEFANI - MAKE ME LIKE YOU 22 156 0 156 MIKE POSNER - I TOOK A PILL IN IBIZA(RNX-2016) 23 153 0 153 JAIN - COME 24 150 0 150 NEISHA - NAJINA SLIKA IN TI 25 150 0 150 DUA LIPA - BE THE ONE 26 149 0 149 AVICII - FOR A BETTER DAY 27 147 0 147 ALYA - SRCE ZA SRCE 28 147 0 147 BIRDY - KEEPING YOUR HEADUP 29 146 0 146 OMI & FELIX JAEHN - CHEERLEADER(RMX) 30 143 0 143 SHAWN MENDES - SOMETHING BIG 31 143 0 143 SHAKIRA - TRY EVERYTHING 32 142 0 142 SIMPLE PLAN & R CITY - SINGING IN THE RAIN 33 137 1 138 JUSTIN BIEBER - LOVE YOURSELF 34 136 0 136 COLDPLAY - ADVENTURE OF A LIFETIME 35 134 0 134 SANS SOUCI & PEARL ANDERSSON - SWEET HARMONY 36 134 0 134 FIRST AID -

A Global Songfest

A GLOBAL SONGFEST Songs of Unity & Hope January 31, 2021 10:00 AM EST www.songfest.us/sf25 Dearest viewers, As we conclude our work on a project that spans a day and circumnavigates our globe, our hearts are filled with gratitude. Gratitude to work with a team that cares deeply, gratitude for faculty who give freely, gratitude for SongFest alumni willing to record these cherished pieces, and finally, gratitude to the artists everywhere who are now linked to the SongFest family through their generosity. From the recordings of Ghanaian folk songs by Legon Palmwine Band to Graham Johnson sharing his encyclopedic knowledge, to friends of friends who have contributed from Indonesia, Chile, Haiti, China, and New Zealand, we are privileged by what unites us: Song. Song is fundamental to communication between cultures. It fills our celebrations and heals us from grief. It deepens emotional connections during our most important moments, and it still has the power to unite us ‘Auf den airwaves’. The song of every region contains the pulse and the stories of its people, flowing with rhythms and melodies born of the earth and elevated through the passage of centuries. It is within this lens that we present our global SongFest, ‘Songs of Unity and Hope’. This is dedicated to our family: the alumni, faculty, and song-lovers around the world. This celebration of the human spirit, expressed through the artistry of over 200 musicians and poets, celebrates 25 years of SongFest and everyone who has dedicated their lives to infusing the world with their art, all on Schubert’s birthday. -

Catalogo MIDI

M-LIVE CATALOGO COMPLETO MIDI - 29/09/2021 COMME FACETTE LA CAMMESELLA MEDLEY ESTATE 2018 - POR UNA CABEZA (TANGO AC/DC 1 MAMMETA LA CUCARACHA VOL.2 STRUMENTALE) BACK IN BLACK CONCERTO D'ARANJUEZ (INSTRUMENTAL) MEDLEY ESTATE 2019 - QUEL MAZZOLIN DI FIORI 10CC HIGHWAY TO HELL CORAZON DE MELON LA CUMPARSITA VOL.1 REGINELLA CAMPAGNOLA YOU SHOOK ME ALL NIGHT I'M NOT IN LOVE CU CU RRU CU CU (INSTRUMENTAL TANGO) MEDLEY ESTATE 2019 - ROMA NUN FA LA STUPIDA LONG PALOMA (ESPANOL) LA GELOSIA NON È PIÙ VOL.2 STASERA ACE OF BASE 2 DEUSTCHLAND UBER DI MODA MEDLEY FOX TROT - VOL.1 ROMA ROMANTIC MEDLEY ALL THAT SHE WANTS ALLES - DAS LIED DER LA GONDOLIERA MEDLEY FOX TROT - VOL.2 RUSTICANELLA (QUANDO 2 EIVISSA CRUEL SUMMER DEUTSCHEN (GERMANY LA MARSEILLAISE (INNO MEDLEY FOX TROT - VOL.3 PASSA LA LEGION...) OH LA LA LA LIFE IS A FLOWER HYMN) NAZIONALE FRANCIA) MEDLEY FOX TROT - VOL.4 SAMBA DE ORFEO 24KGOLDN FT. IANN DIOR LIVING IN DANGER DIMELO AL OIDO LA MONTANARA (VALZER MEDLEY FUNK - 70'S (INSTRUMENTAL) MOOD THE SIGN (INSTRUMENTAL TANGO) LENTO) INSTRUMENTAL SBARAZZINA (VALZER) 2BLACK FT. LOREDANA ACHEVERÈ DO BASI DE FOGO LA PALOMA MEDLEY GIRO D'ITALIA SCIURI SCIURI LUNA DE ORIENTE (SALSA) BERTÈ DON'T CRY FOR ME (INSTRUMENTAL) MEDLEY GRUPPI ANNI 70 - SHAME AND SCANDAL IN WAVES OF LUV (IN ALTO ARGENTINA LA PICCININA VOL.1 THE FAMILY (SKA ACHILLE LAURO MARE) DOVE STA ZAZÀ (INSTRUMENTAL POLCA) MEDLEY HULLY GULLY - VERSION) 1969 2UE EBB TIDE LA PIMPA (SIGLA RAI VOL.2 SICILIANA BRUNA C'EST LA VIE LA TUA IMMAGINE EL BARBUN DI NAVILI YOYO) MEDLEY HULLY GULLY - SILENT NIGHT (ASTRO DEL MALEDUCATA EL CUMBANCHERO LA PUNTITA VOL.3 CIEL) MARILÙ 3 (INSTRUMENTAL) LA VEDOVA ALLEGRA MEDLEY HULLY GULLY - SILENT NIGHT (DANCE ME NE FREGO EL GONDOLIER (INSTRUMENTAL VALZER) VOL.5 RMX) ROLLS ROYCE 360 GRADI ESPANA CANÌ LARGO AL FACTOTUM MEDLEY HULLY GULLY - SIORA GIGIA SOLO NOI BA BA BAY (INSTRUMENTAL PASO (FROM IL BARBIERE DI VOL.7 SOMEWHERE OVER THE ACHILLE LAURO FT. -

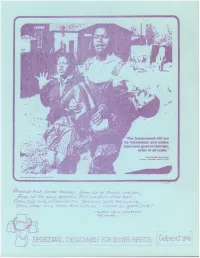

Be Intimidated, and Orders Have Been Given to Maintain Order at All Costs.,"

"The Government will not be Intimidated, and orders have been given to maintain order at all costs.," Prime Mm;stsr *Inv Vomter House of Assembly . Arn 1$, 1976. With ,, . .i... ;-I ,m —ai% :v-.: i :, at., /f.''.)e .,.,-- t,rt/'Pn. i.:/ij e f ::iir 3. ,:e, ) 4 ; ' E/ ,- ; Pty ) .. )'1_ "-, .5t, '‘%. 1r f 4 .7) ..*1 '/"A , .-.,. t ,7,~% :~" ~^'~i v ,:%'f!. =-fi:, d,::A. ,r?,,, 4 '':;,'' rit'.l 'E:K.7r" i T4-i SaTE RTC.1\1 r'') r,r- w't rte" 7-- 1 n 4-1 4, [AdcfEK; 19 . L., t L., Li 1-1 ,i , u T t L-I j SOWETO STUDENTS REPRESENTATIVE COUNCIL October 1976 TO : ALL FATHERS 3c MOTHERS, BROTHERS & SISTERS, FRIENDS & WORKERS, IN ALL CITIES, TOWNS & VILLAGES IN THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA: We appeal to you to align yourselves with the struggle for your own liberation. Be involved and be united with us as it is your own son and daughter that we bury every week-end . Death has become a common thing to us all in the town- ships . There is no peace, there shall be none until we are all free. I . Soweto and all Black townships are now going into a period of MOURNING for the dead . We are to pay respect to all students and adults murdered by the police. 2. We are to pledge our solidarity with those detained in police cells and are suffering torture on our behalf. 3. We should .show our' sympathy and support to all those workers who suffered reduction of wages and loss of jobs because they obeyed our call to stay away from work for three days. -

St. Peter Roman Catholic Parish February 9, 2020

St. Peter Roman Catholic Parish February 9, 2020 BAPTISMS: Celebrated every Sunday by prior arrangement. Parent Baptism Class is held monthly. Please call the rectory for reservations. MARRIAGES: All arrangements must be made at least six months in advance with the pastor. ANOINTING OF THE SICK: If you or a loved one is in need of the Anointing of the Sick, please make arrangements with the parish office. We are happy to visit you with Communion, Confession or to offer the Sacrament of Anointing in your home, hospital or healthcare facility. LETTERS OF RECOMMENDATION: Gladly given to registered parishioners (at least three months) who have received the Sacraments of Initiation, practice their faith regularly, and support the parish. Page Two St. Peter, Lewiston & St. Bernard, Youngstown February 9, 2020 St. Peter’s Mass Intentions Dear Parish Family, Monday February 10 • St Scholastica As a Diocese, we have completed the 33 Days to 7:45 a.m. Nazzareno Gentile by David & Annette Yash Morning Glory Marian Consecration. I would like to congratulate those who have completed the Tuesday February 11 • Weekday consecration. If you began at a later time, I encourage you to continue working through this retreat. It took 7:45 a.m. Josephine Tulimieri by Richard & Sharon Low me three times before I was able to complete it. The first time I was too busy to spend the time doing the Wednesday February 12 • Weekday readings. So, if that happened to you, I’ve been there, done that. Don’t get discouraged, hang in there. Start 7:45 a.m. -

Diary of Daily PRAYER Second Edition Shepherd--Diary 10/20/04 9:13 AM Page I

Diary of Daily PRAYER Second Edition Shepherd--Diary 10/20/04 9:13 AM Page i DIARY OF DAILY PRAYER Second Edition Shepherd--Diary 10/20/04 9:13 AM Page iii DIARY OF DAILY PRAYER Second Edition J. Barrie Shepherd Shepherd--Diary 10/20/04 9:13 AM Page iv © 2002 J. Barrie Shepherd Originally published in 1975 by Augsburg Publishing House All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, record- ing, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writ- ing from the publisher. For information, address Westminster John Knox Press, 100 Witherspoon Street, Louisville, Kentucky 40202-1396. Scripture quotations unless otherwise noted are from the Revised Standard Ver- sion of the Bible, copyright © 1946, 1952, 1971, and 1973 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the U.S.A., and are used by permission. Book design by Sharon Adams Cover design by Pam Poll Graphic Design Published by Westminster John Knox Press Louisville, Kentucky This book is printed on acid-free paper that meets the American National Standards Institute Z39.48 standard. PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 — 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Shepherd, J. Barrie. Diary of daily prayer / J. Barrie Shepherd.— 2nd ed. p. cm. ISBN 0-664-22565-9 1. Prayers. I. -

01-2016 Index Good Short Total Song 1 50 0 50 COLDPLAY

01-2016 Index Good Short Total Song 1 50 0 50 COLDPLAY - ADVENTURE OF A LIFETIME 2 45 0 45 CHARLIE PUTH & MEGHAN TRAINOR - MARVIN GAYE 3 42 0 42 SHAWN MENDES - STITCHES 4 39 0 39 MI2 - BELI GRAD 5 37 0 37 MADCON & RAY DALTON - DON'T WORRY 6 37 0 37 SIDDHARTA - LEDENA 7 35 0 35 ANNA NAKLAB & ALLE FARBEN & YOUNOTUS - SUPERGIRL 8 34 0 34 ADELE - HELLO 9 34 0 34 FIRST AID KIT - MY SILVER LINING 10 29 0 29 ONE DIRECTION - DRAG ME DOWN 11 29 0 29 WEEKEND - CAN'T FEEL MY FACE 12 27 0 27 JASON DERULO - CHEYENNE 13 27 0 27 JUSTIN BIEBER - SORRY 14 26 0 26 OMI & FELIX JAEHN - CHEERLEADER(RMX) 15 25 0 25 TAYLOR SWIFT - WILDEST DREAMS 16 25 0 25 ČEDAHUČI - ČE HOČEŠ GREM 17 25 0 25 FELIX JAEHN & JASMINE THOMPSON - AIN'T NOBODY(LOVES ME BETTER) 18 23 0 23 AVICII - FOR A BETTER DAY 19 23 0 23 JASON DERULO - WANT TO WANT ME 20 23 0 23 ELINA BORN & STIG RASTA - GOODBYE TO YESTERDAY 21 22 0 22 NEISHA - NAJINA SLIKA IN TI 22 22 0 22 MARLON ROUDETTE & K STEWART - EVERYBODY FEELING SOMETHING 23 21 0 21 HOZIER - SOMEONE NEW 24 21 0 21 JAN PLESTENJAK - STARA DOBRA 25 20 0 20 JAMES BAY - HOLD BACK THE RIVER 26 20 0 20 AVTOMOBILI - STOPINJE V SNEGU 27 20 0 20 LOST FREQUENCIES - REALITY 28 20 0 20 PINK - TODAY'S THE DAY 29 19 0 19 ALYA - DOBER DAN 30 19 0 19 MARAAYA - LIVING AGAIN 31 19 0 19 ANJA RUPEL & PIKA BOŽIČ & NUŠA DERENDA & ALENKA GODEC - DOBRO SE IMEJ 32 19 0 19 ROBIN SHULTZ & FRANCESCO YATES - SUGAR 33 19 0 19 SOLO MILA - SANJAM TVOJ GLAS 34 18 0 18 ADAM LEVINE & R.