An Issues-Based Montana Studies Curriculum for Seventh - Tenth Grade Students

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Last Best Place

discover Montana Genuine The Last Best Place GREAT FALLS · MONTANA “the grandest sight I ever beheld...” 1805 · MERIWETHER LEWIS JOURNAL ENTRY Resting on the high plains along Montana’s Rocky Mountain Front Range, Great Falls is located at the confluence of the Missouri and Sun Rivers. This laid-back, hometown community offers delicious restaurants and a vibrant downtown full of unique shops and art galleries. Considered by many to be the birthplace of western art, Great Falls is home to the Charles M. Russell Museum, which houses works from this iconic western artist. The West’s largest Lewis and Clark museum also resides in Great Falls and documents their historic expedition and one of the most difficult legs of the journey, portaging the falls of the Missouri. Striking out from Great Falls in almost any direction will yield some of the most breathtaking venues in North America. With Glacier National Park, Waterton, Canada and the Bob Marshall Wilderness all a short distance away, Great Falls creates the ideal gateway for your Genuine Montana experience. GENUINEMONTANA.COM Black Eagle Falls © Great Falls Tribune · White Cliffs © BLM Glacier National Park Within an easy two-hour drive from Great Falls, hikers and sightseers can explore Glacier National Park. With the largest concentration of remaining glaciers in the lower 48 states, the park’s shining, glaciated peaks, plunging valleys and turquoise-blue lakes make it one of the most dramatic landscapes in North America. Glacier’s untamed vertical spires of banded granite and ice have earned it the nickname “Backbone of the World,” and these peaks are as wild as they are majestic. -

Montana Historical Society, Mining in the Far West, 1862-1920

Narrative Section of a Successful Proposal The attached document contains the narrative and selected portions of a previously funded grant application. It is not intended to serve as a model, but to give you a sense of how a successful proposal may be crafted. Every successful proposal is different, and each applicant is urged to prepare a proposal that reflects its unique project and aspirations. Prospective applicants should consult the program guidelines at http://www.neh.gov/grants/education/landmarks-american-history- and-culture-workshops-school-teachers for instructions. Applicants are also strongly encouraged to consult with the NEH Division of Education Programs staff well before a grant deadline. The attachment only contains the grant narrative and selected portions, not the entire funded application. In addition, certain portions may have been redacted to protect the privacy interests of an individual and/or to protect confidential commercial and financial information and/or to protect copyrighted materials. Project Title: The Richest Hills: Mining in the Far West, 1862-1920 Institution: Montana Historical Society Project Directors: Kirby Lambert and Paula Petrik Grant Program: Landmarks of American History and Culture Workshops 400 7th Street, S.W., 4th Floor, Washington, D.C. 20506 P 202.606.8500 F 202.606.8394 E [email protected] www.neh.gov LANDMARKS OF AMERICAN HISTORY TEACHER WORKSHOP THE RICHEST HILLS: MINING IN THE FAR WEST, 1862–1920 A. Narrative: The Montana Historical Society seeks support for a Landmarks of American History and Culture workshop for teachers that will examine the historical and cultural issues accompanying the development of mining in the far West. -

History of Navigation on the Yellowstone River

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1950 History of navigation on the Yellowstone River John Gordon MacDonald The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation MacDonald, John Gordon, "History of navigation on the Yellowstone River" (1950). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 2565. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/2565 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HISTORY of NAVIGATION ON THE YELLOWoTGriE RIVER by John G, ^acUonald______ Ë.À., Jamestown College, 1937 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Mas ter of Arts. Montana State University 1950 Approved: Q cxajJL 0. Chaiinmaban of Board of Examiners auaue ocnool UMI Number: EP36086 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Ois8<irtatk>n PuUishing UMI EP36086 Published by ProQuest LLC (2012). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. -

5340 Exchanges Missoula, Ninemile, Plains/Thompson

5340 EXCHANGES MISSOULA, NINEMILE, PLAINS/THOMPSON FALLS, SEELEY LAKE, AND SUPERIOR RANGER DISTRICTS LOLO NATIONAL FOREST MONTANA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES AND CONSERVATION LAND EXCHANGE MTM 92893 MINERAL POTENTIAL REPORT Minerals Examiner: _____________________________________ Norman B. Smyers, Geologist-Lolo and Flathead National Forests _____________________________________ Date Regional Office Review: _____________________________________ Michael J. Burnside, Northern Region Certified Review Mineral Examiner _____________________________________ Date Abstract-DNRC/Lolo NF Land Exchange Mineral Report: Page A-1 ABSTRACT The non-federal and federal lands involved in the proposed Montana Department of Natural Resources and Conservation (DNRC) Land Exchange are located across western Montana and within the exterior boundaries of the lands administered by the Lolo National Forest. The proposed land exchange includes approximately 12,123 acres of non-federal land and 10,150 acres of federal land located in six counties--Granite, Lincoln, Missoula, Mineral, Powell, and Sanders. For the Federal government, the purpose of the exchange is to improve land ownership patterns for more efficient and effective lands management by: reducing the need to locate landline and survey corners; reducing the need for issuing special-use and right-of-way authorizations; and facilitating the implementation of landscape level big game winter range vegetative treatments. With the exception of one DNRC parcel and six Federal parcels, the mineral estates of the parcels involved in the proposed land exchange are owned by either the State of Montana or the U.S. Government and can be conveyed with the corresponding surface estates. The exceptions are: the DNRC Sunrise parcel; and, for the U.S. Government, the Graham Mountain 2,Graham Mountain 10, Fourmile 10, St. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Rev. Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM 1. Name of Property historic name: Dearborn River High Bridge other name/site number: 24LC130 2. Location street & number: Fifteen Miles Southwest of Augusta on Bean Lake Road not for publication: n/a vicinity: X city/town: Augusta state: Montana code: MT county: Lewis & Clark code: 049 zip code: 59410 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this _X_ nomination _ request for detenj ination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the proc urf I and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property X_ meets _ does not meet the National Register Criterfi commend thatthis oroperty be considered significant _ nationally X statewide X locafly. Signa jre of oertifying officialn itle Date Montana State Historic Preservation Office State or Federal agency or bureau (_ See continuation sheet for additional comments. In my opinion, the property _ meets _ does not meet the National Register criteria. Signature of commenting or other official Date State or Federal agency and bureau 4. National Park Service Certification , he/eby certify that this property is: 'entered in the National Register _ see continuation sheet _ determined eligible for the National Register _ see continuation sheet _ determined not eligible for the National Register_ _ see continuation sheet _ removed from the National Register _see continuation sheet _ other (explain): _________________ Dearborn River High Bridge Lewis & Clark County. -

Great Falls Montana Tourism Marketing Strategy

Great Falls Montana Tourism Marketing Strategy April 2017 Executive Summary Great Falls Montana Tourism has begun an ambitious initiative to attract more visitors to the City of Great Falls, supporting its growth and bolstering its economy. Successful tourism attraction will depend on the highly-targeted engagement of Great Falls’ audience groups – people looking for a vacation or meeting experience centered around the assets Great Falls has to offer. Great Falls Montana Tourism has engaged Atlas to develop a comprehensive tourism marketing strategy for the city to guide tourism attraction tactics and campaigns for maximum impact. To develop an effective strategy, Atlas has: • Assessed Great Falls’ tourism strengths and weaknesses, and the opportunities and threats, to growing the tourism economy, along with an analysis of in-state and regional competing communities • Performed a national survey of professional meeting planners to gauge the perception of Great Falls as a meeting destination, including respondents that have actively planned meetings in Great Falls and those who have not • Researched Great Falls’ online reputation on popular travel websites, including TripAdvisor, Yelp, Google Maps, and Facebook • Interviewed Great Falls Montana Tourism leadership and reviewed the previous, internally-developed marketing plan and tourism brand package and its supporting research developed by North Star Destination Strategies From this foundation of analysis and research, Atlas developed the positioning statement for Great Falls as a tourism -

Cover Page and Intro 2006 AWRA MB.Pub

PROCEEDINGS for Montana’s Lakes and Wetlands: Improving Integrated Water Management 23rd Annual Meeting of the MONTANA SECTION of the American Water Resources Association Polson, Montana October 12th and 13th, 2006 KawTuqNuk Inn Contents Thanks to Planners and Sponsors Full Meeting Agenda About the Keynote Speakers Concurrent Session and Poster Abstracts* Session 1. Wetlands and Streams Session 2. Mining and Water Quality Session 3. Ground Water and Surface Water Studies Session 4. Sediment, Channel Processes, Floodplains and Reservoir Management Poster Session Meeting Attendees *These abstracts were not edited and appear as submitted by the author, except for some changes in font and format. THANKS TO ALL WHO MAKE THIS EVENT POSSIBLE! • The AWRA Officers Kate McDonald, President, Ecosystem Research Group Tammy Crone, Treasurer, Gallatin Local Water Quality District Mike Roberts, Montana Department of Natural Resources and Conservation May Mace, Montana Section Executive Secretary • Montana Water Center, Meeting Coordination Molly Boucher, Sue Faber, Susan Higgins, MJ Nehasil, Gretchen Rupp • Our Generous Sponsors (please see next page) Maxim Technologies, DEQ Wetlands Program, Montana Water Center, HydroSolutions Inc, and Watershed Consulting LLC • And especially, the many dedicated presenters, field trip leaders, moderators, student paper judges, and student volunteers Meeting planners Sue Higgins, May Mace, Lynda Saul, Tammy Crone, Mike Roberts and Katie McDonald. THE 2006 MEETING SPONSORS Major Sponsors (Watershed) Supporting Sponsors (River) Contributing Sponsors (Tributary) American Water Resources Association Montana Section’s 23rd Annual Meeting KawTuqNuk Inn, Polson, Montana October 12 and 13, 2006 AGENDA MONTana’S LAKES and WETlandS: IMPROVing INTegRATed WATER ManagemenT WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 11, 2006 8:00 am – 10:00 am REGISTRATION, KawTuqNuk, Lower Lobby 9:00 am – 4:00 pm Free Wetlands Identification Workshop with Pete Husby and Dr. -

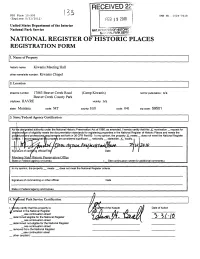

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NFS Form 10-900 0MB No. 1024-0018 (Expires 5/31/2012) FEB 1 9 2010 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NAT. RreWTEFi OF HISTORIC '• NAPONALPARKSEFWI NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM 1. Name of Property historic name: Kiwanis Meeting Hall other name/site number: Kiwanis Chapel 2. Location street & number: 17863 Beaver Creek Road (Camp Kiwanis) not for publication: n/a Beaver Creek County Park city/town: HAVRE vicinity: n/a state: Montana code: MT county: Hill code: 041 zip code: 59501 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As tr|e designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify t that this X nomination _ request for deti jrminalon of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Regist er of Historic Places and meets the pro i^duraland professional/equiremants set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property X meets _ _ does not meet the National Register Crlt jfria. I JecommendJhat tnis propeay be considered significant _ nationally _ statewide X locally, i 20 W V» 1 ' Signature of certifj^ng official/Title/ Date / Montana State Historic Preservation Office State or Federal agency or bureau ( See continuation sheet for additional comments.) In my opinion, the property _ meets _ does not meet the National Register criteria. Signature of commenting or other official Date State or Federal agency and bureau 4. National Park Service Certification I, hereby certify that this property is: Date of Action entered in the National Register _ see continuation sheet _ determined eligible for the National Register *>(.> 10 _ see continuation sheet _ determined not eligible for the National Register _ see continuation sheet _ removed from the National Register _see continuation sheet _ other (explain): _________________ Kiwanis Meeting Hall Hill County. -

East Bench Unit History

East Bench Unit Three Forks Division Pick Sloan Missouri Basin Program Jedediah S. Rogers Bureau of Reclamation 2008 Table of Contents East Bench Unit...............................................................2 Pick Sloan Missouri Basin Program .........................................2 Project Location.........................................................2 Historic Setting .........................................................3 Investigations...........................................................7 Project Authorization....................................................10 Construction History ....................................................10 Post Construction History ................................................15 Settlement of Project Lands ...............................................19 Project Benefits and Uses of Project Water...................................20 Conclusion............................................................21 Bibliography ................................................................23 Archival Sources .......................................................23 Government Documents .................................................23 Books ................................................................24 Other Sources..........................................................24 1 East Bench Unit Pick Sloan Missouri Basin Program Located in rural southwest Montana, the East Bench Unit of the Pick Sloan Missouri Basin Program provides water to 21,800 acres along the Beaverhead River in -

A HISTORY OP FORT SHAW, MONTANA, from 1867 to 1892. by ANNE M. DIEKHANS SUBMITTED in PARTIAL FULFILLMENT of "CUM LAUDE"

A HISTORY OP FORT SHAW, MONTANA, FROM 1867 TO 1892. by ANNE M. DIEKHANS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF "CUM LAUDE" RECOGNITION to the DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY CARROLL COLLEGE 1959 CARROLL COLLEGE LIBRARY HELENA, MONTANA MONTANA COLLECTION CARROLL COLLEGE LIBRAS/- &-I THIS THESIS FOR "CUM LAUDE RECOGNITION BY ANNE M. DIEKHANS HAS BEEN APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY Date ii PREFACE Fort Shaw existed as a military post between the years of 1867 and 1892. The purpose of this thesis is to present the history of the post in its military aspects during that period. Other aspects are included but the emphasis is on the function of Fort Shaw as district headquarters of the United States Army in Montana Territory. I would like to thank all those who assisted me in any way in the writing of this thesis. I especially want to thank Miss Virginia Walton of the Montana Historical Society and the Rev. John McCarthy of the Carroll faculty for their aid and advice in the writing of this thesis. For techni cal advice I am indebted to Sister Mary Ambrosia of the Eng lish department at Carroll College. I also wish to thank the Rev. James R. White# Mr. Thomas A. Clinch, and Mr. Rich ard Duffy who assisted with advice and pictures. Thank you is also in order to Mrs. Shirley Coggeshall of Helena who typed the manuscript. A.M.D. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Chggter Page I. GENERAL BACKGROUND............................... 1 II. MILITARY ACTIVITIES............................. 14 Baker Massacre Sioux Campaign The Big Hole Policing Duties Escort and Patrol Duties III. -

Montana: the Last, Best Place?

CHAPTER 2 Montana: The Last, Best Place? o understand politics in Montana and the process of representation, one T does not begin with people or politicians. One begins with place, because without place the rest does not—cannot—be made to make sense. How Montanans understand themselves, their representatives, their history, and their relationship to others—including the federal government—begins and ends with place. It is also place that presents Montanans with their greatest challenges and opportuni- ties. To use Richard Fenno’s terminology, we must begin with the geographic constituency—not only as a physical space and place, but as a shared idea and experience. To understand Montana and Montanans, we must start with the land known variously as the Treasure State, Big Sky Country,distribute or perhaps the most evocative: The Last, Best Place. In this chapter, I provide the reader with a short historyor of Montana’s relation- ship to the land, its historical development, the complicated relationship it has with the federal government, and the challenges the state faces as it transitions from a resource-intensive economy to a more diverse one based upon tourism and hi-tech industries. I claim that the deep connection Montanans have with their physical surroundings shapes howpost, they view politics, the cleavages which exist among them, and the representatives they choose to represent them. Place also dictates the representational choices members of Congress make to build trust with their constituents. In particular, members of Congress are careful to cultivate a representational style known as “one of us” with their constituents. -

Work House a Science and Indian Education Program with Glacier National Park National Park Service U.S

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Glacier National Park Work House a Science and Indian Education Program with Glacier National Park National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Glacier National Park “Work House: Apotoki Oyis - Education for Life” A Glacier National Park Science and Indian Education Program Glacier National Park P.O. Box 128 West Glacier, MT 59936 www.nps.gov/glac/ Produced by the Division of Interpretation and Education Glacier National Park National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Washington, DC Revised 2015 Cover Artwork by Chris Daley, St. Ignatius School Student, 1992 This project was made possible thanks to support from the Glacier National Park Conservancy P.O. Box 1696 Columbia Falls, MT 59912 www.glacier.org 2 Education National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Glacier National Park Acknowledgments This project would not have been possible without the assistance of many people over the past few years. The Appendices contain the original list of contributors from the 1992 edition. Noted here are the teachers and tribal members who participated in multi-day teacher workshops to review the lessons, answer questions about background information and provide additional resources. Tony Incashola (CSKT) pointed me in the right direc- tion for using the St. Mary Visitor Center Exhibit information. Vernon Finley presented training sessions to park staff and assisted with the lan- guage translations. Darnell and Smoky Rides-At-The-Door also conducted trainings for our education staff. Thank you to the seasonal education staff for their patience with my work on this and for their review of the mate- rial.