Successful Fire Blight Control Is in the Details

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Apples Catalogue 2019

ADAMS PEARMAIN Herefordshire, England 1862 Oct 15 Nov Mar 14 Adams Pearmain is a an old-fashioned late dessert apple, one of the most popular varieties in Victorian England. It has an attractive 'pearmain' shape. This is a fairly dry apple - which is perhaps not regarded as a desirable attribute today. In spite of this it is actually a very enjoyable apple, with a rich aromatic flavour which in apple terms is usually described as Although it had 'shelf appeal' for the Victorian housewife, its autumnal colouring is probably too subdued to compete with the bright young things of the modern supermarket shelves. Perhaps this is part of its appeal; it recalls a bygone era where subtlety of flavour was appreciated - a lovely apple to savour in front of an open fire on a cold winter's day. Tree hardy. Does will in all soils, even clay. AERLIE RED FLESH (Hidden Rose, Mountain Rose) California 1930’s 19 20 20 Cook Oct 20 15 An amazing red fleshed apple, discovered in Aerlie, Oregon, which may be the best of all red fleshed varieties and indeed would be an outstandingly delicious apple no matter what color the flesh is. A choice seedling, Aerlie Red Flesh has a beautiful yellow skin with pale whitish dots, but it is inside that it excels. Deep rose red flesh, juicy, crisp, hard, sugary and richly flavored, ripening late (October) and keeping throughout the winter. The late Conrad Gemmer, an astute observer of apples with 500 varieties in his collection, rated Hidden Rose an outstanding variety of top quality. -

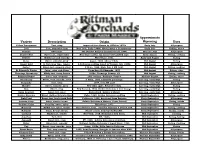

Variety Description Origin Approximate Ripening Uses

Approximate Variety Description Origin Ripening Uses Yellow Transparent Tart, crisp Imported from Russia by USDA in 1870s Early July All-purpose Lodi Tart, somewhat firm New York, Early 1900s. Montgomery x Transparent. Early July Baking, sauce Pristine Sweet-tart PRI (Purdue Rutgers Illinois) release, 1994. Mid-late July All-purpose Dandee Red Sweet-tart, semi-tender New Ohio variety. An improved PaulaRed type. Early August Eating, cooking Redfree Mildly tart and crunchy PRI release, 1981. Early-mid August Eating Sansa Sweet, crunchy, juicy Japan, 1988. Akane x Gala. Mid August Eating Ginger Gold G. Delicious type, tangier G Delicious seedling found in Virginia, late 1960s. Mid August All-purpose Zestar! Sweet-tart, crunchy, juicy U Minn, 1999. State Fair x MN 1691. Mid August Eating, cooking St Edmund's Pippin Juicy, crisp, rich flavor From Bury St Edmunds, 1870. Mid August Eating, cider Chenango Strawberry Mildly tart, berry flavors 1850s, Chenango County, NY Mid August Eating, cooking Summer Rambo Juicy, tart, aromatic 16th century, Rambure, France. Mid-late August Eating, sauce Honeycrisp Sweet, very crunchy, juicy U Minn, 1991. Unknown parentage. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Burgundy Tart, crisp 1974, from NY state Late Aug.-early Sept. All-purpose Blondee Sweet, crunchy, juicy New Ohio apple. Related to Gala. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Gala Sweet, crisp New Zealand, 1934. Golden Delicious x Cox Orange. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Swiss Gourmet Sweet-tart, juicy Switzerland. Golden x Idared. Late Aug.-early Sept. All-purpose Golden Supreme Sweet, Golden Delcious type Idaho, 1960. Golden Delicious seedling Early September Eating, cooking Pink Pearl Sweet-tart, bright pink flesh California, 1944, developed from Surprise Early September All-purpose Autumn Crisp Juicy, slow to brown Golden Delicious x Monroe. -

Reliable Fruit Tree Varieties for Santa Cruz County

for the Gardener Reliable Fruit Tree Varieties for Santa Cruz County lanting a fruit tree is, or at least should be, a considered act involving a well thought-out plan. In a sense, you “design” a tree, or by extension, an orchard—and as tempting as it may be to grab a shovel and start digging, the Plast thing you do is plant the tree. There are many elements to the plan for successful deciduous fruit tree growing. They include, but are not limited to – • Site selection • Sanitation, particularly on the orchard floor • Soil—assessment and improvement • Weed management • Scale and diversity of the planting • Pruning/training systems • What genera and species (apple, pear, plum, • Thinning peach, etc.) and what varieties grow well in an area • Pest and disease control • Pollination • Sourcing quality trees • Irrigation • The planting hole and process • A fertility plan and associated fertilizers • Harvest and post-harvest All of the above factors comprise the jigsaw puzzle or the Rubik’s Cube of fruit growing. In essence, you must align all the colored cubes to induce smiles on the faces of both growers and consumers. This article focuses on the selection of genera, species, and varieties that do well in Santa Cruz County, and discusses chill hour requirements as one major criterion for successful fruit tree growing. THE RELIABLE—AND NOT SO RELIABLE What Grows Well Here By “what grows well,” I mean what produces a reliable annual crop and is relatively disease and pest free. In Santa Cruz County, that includes— • Apples • Pluots • Pears -

Diseases of Trees in the Great Plains

United States Department of Agriculture Diseases of Trees in the Great Plains Forest Rocky Mountain General Technical Service Research Station Report RMRS-GTR-335 November 2016 Bergdahl, Aaron D.; Hill, Alison, tech. coords. 2016. Diseases of trees in the Great Plains. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-335. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 229 p. Abstract Hosts, distribution, symptoms and signs, disease cycle, and management strategies are described for 84 hardwood and 32 conifer diseases in 56 chapters. Color illustrations are provided to aid in accurate diagnosis. A glossary of technical terms and indexes to hosts and pathogens also are included. Keywords: Tree diseases, forest pathology, Great Plains, forest and tree health, windbreaks. Cover photos by: James A. Walla (top left), Laurie J. Stepanek (top right), David Leatherman (middle left), Aaron D. Bergdahl (middle right), James T. Blodgett (bottom left) and Laurie J. Stepanek (bottom right). To learn more about RMRS publications or search our online titles: www.fs.fed.us/rm/publications www.treesearch.fs.fed.us/ Background This technical report provides a guide to assist arborists, landowners, woody plant pest management specialists, foresters, and plant pathologists in the diagnosis and control of tree diseases encountered in the Great Plains. It contains 56 chapters on tree diseases prepared by 27 authors, and emphasizes disease situations as observed in the 10 states of the Great Plains: Colorado, Kansas, Montana, Nebraska, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Texas, and Wyoming. The need for an updated tree disease guide for the Great Plains has been recog- nized for some time and an account of the history of this publication is provided here. -

Managing Fire Blight by Choosing Decreased Host Susceptibility Levels and Rootstock Traits , 2020 , January 15 January

Managing Fire Blight by Choosing Decreased Host Susceptibility Levels and Rootstock Traits , 2020 , January 15 January Awais Khan Plant Pathology and Plant-microbe Biology, SIPS, Cornell University, Geneva, NY F ire blight bacterial infection of apple cells Khan et al. 2013 Host resistance and fire blight management in apple orchards Host resistance is considered most sustainable option for disease management due to Easy to deploy/implement in the orchards Low input and cost-effective Environment friendly No choice to the growers--most of the new and old cultivars are highly susceptible Apple breeding to develop resistant cultivars Domestication history of the cultivated apple 45-50 Malus species-----Malus sieversii—Gene flow Malus baccata Diameter: 1 cm Malus sieversii Malus baccata Diameter: up to 8 cm Malus orientalis Diameter: 2-4 cm Malus sylvestris Diameter: 1-3 cm Duan et al. 2017 Known sources of major/moderate resistance to fire blight to breed resistant cultivars Source Resistance level Malus Robusta 5 80% Malus Fusca 66% Malus Arnoldiana, Evereste, Malus floribunda 821 35-55% Fiesta, Enterprise 34-46% • Fruit quality is the main driver for success of an apple cultivar • Due to long juvenility of apples, it can take 20-25 years to breed resistance from wild crab apples Genetic disease resistance in world’s largest collection of apples Evaluation of fire blight resistance of accessions from US national apple collection o Grafted 5 replications: acquired bud-wood and rootstocks o Inoculated with Ea273 Erwinia amylovora strain -

Tree Diseases

Tree Diseases In North Texas home owners cherish their trees for their beauty and for their shade protection from summer’s sun. Unfortunately, trees can experience problems that affect their attractive appearance and may even lead to death. Trees are vulnerable to environmental stress, infectious diseases, insects and human-caused damage. Correctly diagnosing the cause of a tree’s problem is the most important step in successful treatment. To determine if your tree has a disease, examine the whole tree not just the area showing symptoms suggests Iowa State University Extension Service (Diagnosing Tree Problems). Check leaves for holes or ragged edges, discoloration or deformities Look at the tree’s trunk for damage to the bark such as cracks or splits Consider previous activity that may have impacted the tree’s root system such as planting shrubs nearby or construction of a sidewalk or adding hardscape like a deck or patio The following diseases occur in Denton County. This is not all-inclusive, but Master Gardeners have seen all of these (with the exception of oak wilt). If you need help diagnosing a tree problem, send a picture of the entire tree and close-ups of the problem area(s) to the help desk at [email protected]. If it is a new tree, include a picture of the bottom of the trunk where it meets the soil. Include such information as: Age of the tree When the problem was noticed Sudden or gradual onset Presence of insects Anything else you believe is relevant Anthracnose This fungus is usually on lower branches, following a cool, wet, spring. -

Assessment of One Year of Growth in the New Jersey Hard Cider Variety Trial M

Assessment of One Year of Growth in the New Jersey Hard Cider Variety Trial M. Muehlbauer and R. Magron Rutgers University There is much interest in hard cider in New Jersey. the best apples for their cider. Some traditional fresh In New Jersey the manufacture of hard cider is covered market apples make good hard cider, but many of the under the Farm Winery Act, passed in 1981. NJ law hard cider producers are looking for both the English treats hard cider as a type of wine as it is fermented and French hard cider varieties to source for production from fruits (N.J.A.C. 18:3-1.2) of craft hard ciders. As such there is much interest from existing sweet Apple growers and hard cider producers are look- cider producers to make and sell hard cider as a value ing to source these hard cider apple varieties that have added product. There is also great interest and for the specifi c characteristics for craft hard cider. There is an establishment of new, stand alone hard cideries. NJ now abundant interest and momentum from these NJ hard has a mix of both established, seen the list at https:// cider producers to evaluate and grow or purchase these www.ciderculture.com/cideries/state/nj/ varieties from other apple growers. These hard cider producers all need a supply of As a result, it is important to establish a demonstra- ϴϬ ϳϬ ϲϬ ϱϬ ϰϬ ϯϬ ϮϬ $YHUDJH +HLJKW LQ $YHUDJH 'LDPHWHU PP ϭϬ Ϭ /RGL 0DMRU /LQGHO 0DUJLO &ROODRV 'DELQHWW +DUULVRQ :LFNVRQ )R[ZKHOS 0DULDOHQD %ODQTXLQD (OOLV%LWWHU 3LQN3HDUO 6WRNH5HG 3LHOGH6DSD &DOYLOOH%ODQF %OXH3HDUPDLQ -

Fire Blight of Apple and Pear

WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY EXTENSION Fire Blight of Apple and Pear Updated by Tianna DuPont, WSU Extension, February 2019. Original publication by Tim Smith, Washington State University Tree Fruit Extension Specialist Emeritus; David Granatstein, Washington State University; Ken Johnson, Professor of Plant Pathology Oregon State University. Overview Fire blight is an important disease affecting pear and apple. Infections commonly occur during bloom or on late blooms during the three weeks following petal fall. Increased acreage of highly susceptible apple varieties on highly susceptible rootstocks has increased the danger that infected blocks will suffer significant damage. In Washington there have been minor outbreaks annually since 1991 and serious damage in about 5-10 percent of orchards in 1993, 1997, 1998, 2005, Figure 2 Bloom symptoms 12 days after infection. Photo T. DuPont, WSU. 2009, 2012, 2015, 2016, 2017 and 2018. Shoot symptoms. Tips of shoots may wilt rapidly to form a Casual Organism “shepherd’s crook.” Leaves on diseased shoots often show blackening along the midrib and veins before becoming fully Fire blight is caused by Erwinia amylovora, a gram-negative, necrotic, and cling firmly to the host after death (a key rod-shaped bacterium. The bacterium grows by splitting its diagnostic feature.) Numerous diseased shoots give a tree a cells and this rate of division is regulated by temperature. Cell burnt, blighted appearance, hence the disease name. division is minimal below 50 F, and relatively slow at air temperatures between 50 to 70 F. At air temperatures above 70 F, the rate of cell division increases rapidly and is fastest at 80 F. -

Cherry Fire Blight

ALABAMA A&M AND AUBURN UNIVERSITIES Fire Blight on Fruit Trees and Woody Ornamentals ANR-542 ire blight, caused by the bac- Fterium Erwinia amylovora, is a common and destructive dis- ease of pear, apple, quince, hawthorn, firethorn, cotoneaster, and mountain ash. Many other members of the rose plant family as well as several stone fruits are also susceptible to this disease (Table 1). The host range of the Spur blight on crabapple fire blight pathogen includes cv ‘Mary Potter’. nearly 130 plant species in 40 genera. Badly diseased trees and symptoms are often referred to shrubs are usually disfigured and as blossom blight. The blossom may even be killed by fire blight phase of fire blight affects blight. different host plants to different degrees. Fruit may be infected Symptoms by the bacterium directly through the skin or through the The term fire blight describes stem. Immature fruit are initially Severe fire blight on crabapple the blackened, burned appear- water-soaked, turning brownish- cv ‘Red Jade’. ance of damaged flowers, twigs, black and becoming mummified and foliage. Symptoms appear in as the disease progresses. These Shortly after the blossoms early spring. Blossoms first be- mummies often cling to the trees die, leaves on the same spur or come water-soaked, then wilt, for several months. shoot turn brown on apple and and finally turn brown. These most other hosts or black on Table 1. Plant Genera That Include Fire Blight Susceptible Cultivars. Common Name Scientific Name Common Name Scientific Name Apple, Crabapple Malus Jetbead Rhodotypos -

Fireblight–An Emerging Problem for Blackberry Growers in the Mid-South

North American Bramble Growers Research Foundation 2016 Report Fire Blight: An Emerging Problem for Blackberry Growers in the Mid-South Principal Investigator: Burt Bluhm University of Arkansas Department of Plant Pathology 206 Rosen Center Voice: (479) 575-2677 Fax: (479) 575-7601 Julia Stover University of Arkansas Department of Plant Pathology 211 Rosen Center A poster with many of these initial findings was presented at the North American Berry Conference in Grand Rapids, MI in December 2016 Background and Initial Rationale: Fire blight, caused by the bacterial pathogen Erwinia amylovora, infects all members of the family Rosaceae and is considered to be the single most devastating bacterial disease of apple. Erwinia amylovora was first isolated from blighted blackberry plants in Illinois in 1976, from both mummified fruit and blighted canes (Ries and Otterbacher, 1977). These symptoms had been sporadically reported previously in both blackberry and raspberry, but the causal agent had never been identified. Since this first report, the disease has been found throughout the blackberry growing regions of the United States, but is generally not considered to be a pathogen of major concern (Smith, 2014; Clark, personal communication). However, with the advent of primocane fruiting plants, a significant increase in disease incidence has been witnessed in Arkansas (Garcia, personal communication) and fruit loss of up to 65% has been reported in Illinois (Schilder, 2007). Fire blight is a disease that is very environmentally dependent, and warm, wet weather at flowering is most conducive to serious disease development. The Arkansas growing conditions are ideal for disease development, and the shift in production season with primocane fruiting moves flowering time to a time of year with temperatures cool enough for bacterial growth (Smith, 2014). -

Home Orchards Disease and Insect Control Recommendations

INTEGRATED PEST MANAGEMENT Home Orchards Disease and Insect Control Recommendations Apple and Pear Apple and pear trees are subject to serious damage from pests. As a result, a preventive spray program is needed. The following practices will improve the effectiveness of the pesticides and may lessen the need for sprays. ■ Plant disease-resistant varieties. This method of disease control is especially important for fire blight, where chemical control options are limited. Varieties resistant to cedar-apple rust, scab, and powdery mildew also are available and will potentially reduce the need for sprays. ■ Rake and destroy leaves in the fall if apple scab or pear leaf spot are problems. The fungi that cause these diseases can survive through the winter in ■ Prune out and destroy all dead or diseased shoots infected leaves. and limbs during the dormant season. This helps to reduce fire blight, fruit rots, and certain leaf spots, ■ Remove diseased galls from cedar trees. Spores as the organisms that cause these diseases can from these cedars can infect apples, causing cedar- survive through the winter in the wood. Removing apple rust. Elimination of the source of spores (cedar mummified (dark, shriveled, dry) fruit helps to prevent trees) is effective but not always possible. Where the overwintering of the fruit rot organisms. cedars are part of an established landscape, remove and destroy all galls caused by the rust fungus on ■ Prune out fire blight–affected shoots and blossom cedars in the late fall. Inspect the cedars again in clusters during the growing season only as symptoms the early spring during or just after a rain when the appear. -

Fire Blight of Pears and Apples,” Utah Plant Disease Control No

UtahUtah Pest Factsheet Published by Utah State University Extension and Utah Plant Pest Diagnostic Laboratory PLP-009 June 2008 Adapted from “Fire Blight of Pears and Apples,” Utah Plant Disease Control No. 27, Revised 2000. Fire Blight Kent Evans, Extension Plant Pathology Specialist been found in all pear and apple-producing areas Erin Frank, USU Plant Disease Diagnostician in the United States, as well as in New Zealand and Taun Beddes, Cache County Extension Agent Europe. Erwinia amylovora has the ability to infect many Mike Pace, Box Elder County Extension Agent ornamental plants of the rose family, but is particularly Maggie Shao, Salt Lake County Extension Agent important on pear and apple. It not only destroys the Alicia Moulton, Wasatch County Extension Agent current season’s crop, but may damage the structure of the tree and reduce subsequent production. Highly What You Should Know susceptible trees may be killed in a single season. Fire blight is a bacterial disease of rosaceous plants. Economically, it is most serious on pears and apples. Symptoms The bacterium that causes fire blight, Erwinia amylovora, can be spread by insects, contaminated pruning or graft- Fire blight symptoms are easily recognized by the ing tools, infected grafts, and any manner that carries scorched appearance of leaves, blossoms, and young the bacterial pathogen from an infected plant to one that terminal shoots. Initial infection causes wilt; infected tis- is not, including wind and rain-splash. Pear and apple sue and tissue outward of infections turns black on pear are most susceptible at flowering, but actively growing and brown on apple.