Strategic Perspectives for Bilateral Energy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Negotiating Energy Diplomacy and Its Relationship with Foreign Policy and National Security

International Journal of Energy Economics and Policy ISSN: 2146-4553 available at http: www.econjournals.com International Journal of Energy Economics and Policy, 2020, 10(2), 1-6. Negotiating Energy Diplomacy and its Relationship with Foreign Policy and National Security Ana Bovan1, Tamara Vučenović1, Nenad Perić2* 1Metropolitan University, Faculty of Management, Belgrade, Serbia, 2Faculty for Diplomacy and Security, Belgrade, Serbia. *Email: [email protected] Received: 19 September 2019 Accepted: 01 December 2019 DOI: https://doi.org/10.32479/ijeep.8754 ABSTRACT Energy diplomacy is a complex field of international relations, closely linked to its principal, foreign policy and overall national security. We observe the relationship of issues that belong to the three concepts and how they are intertwined in the geopolitical reality. Despite the ontological hierarchy of the three concepts, where national security is on the highest level of generality, and energy diplomacy on the lowest, it is a recurring theme for them to continuously meet and intersect in realpolitik in a dynamic relationship. The article specifically looks at the integration of energy diplomacy into foreign policy. We discuss two pathways that energy diplomacy has taken on its integration course into foreign policy, namely the path marked by national security topics and the path that is dominantly an economic one. The article also observes the nexus of national security, foreign policy, economic security and economic diplomacy, which is termed the energy security paradox. It exemplifies the inconsistencies in the general state of affairs in which resource riches of a country result in a stable exporter status and consequentially, stable exporting energy diplomacy. -

Climate Diplomacy

2014 Edition NEW PATHS FOR CLIMATE DIPLOMACY leGal notice NEW PATHS FOR The climate diplomacy initiative is a collaborative effort of the Federal Foreign Office in partnership with adelphi, a leading Berlin-based think tank for applied research, policy analysis, and consultancy on global change issues. CLIMATE DIPLOMACY This publication by adelphi research gemeinnützige GmbH is supported by a grant from the German Federal Foreign Office. www.adelphi.de www.auswaertiges-amt.de Authors Paola Adriázola Alexander Carius Laura Griestop Lena Ruthner Dennis Tänzler Joe Thwaites Stephan Wolters Design stoffers/steinicke www.stoffers-steinicke.de © adelphi, 2014 Foreword Climate Diplomacy – a Foreign Policy Challenge for the 21st Century limate change is one of the most important chal- organisations. In reaching out to partners around the world, we seek to raise awareness lenges that humanity collectively faces in the 21st and explore new ideas on how to best mitigate the effects of climate change in interna- C century. As the recently published Fifth Assess- tional relations. At the initiative’s core is the conviction that we require a new, preventive ment Report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate foreign policy approach: an approach that anticipates climate-induced conflicts of the Change shows, with greater certainty than ever, global future, builds trust now between the stakeholders of those future conflicts, strengthens warming is taking place and is caused by greenhouse the institutions and governance structures needed to address them or develops new forums gas emissions deriving from human activity. The effects for dialogue where they will be needed in future, but where none exist at present. -

Annual Report, 2015. KEGOC JSC

ANNUAL REPORT 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS KEGOC, 2015: KEY OPERATIONAL INDICATORS 03 KEY FINANCIAL INDICATORS 04 ABOUT COMPANY 06 LETTER FROM THE CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS 08 LETTER FROM THE CHAIRMAN OF MANAGEMENT BOARD 10 KEY EVENTS IN 2015 12 MARKET OVERVIEW 14 State Regulation and Structure of Power Industry in Kazakhstan 14 Kazakhstan Electricity Market 16 Electricity Balance 21 KAZAKHSTAN POWER SECTOR DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY 27 KEGOC DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY 27 GOAL 1. NPG RELIABILITY 30 Geography of Operations 32 Description of NPG Facilities 34 Dispatch Control Management 35 GOAL 2. NPG DEVELOPMENT 36 Investment Activity 38 Business Outlook 41 GOAL 3. EFFICIENCY IMPROVEMENT 42 Electricity Transmission 44 Technical Dispatch Control 45 Electricity Production and Consumption Balancing 47 Reliability and Energy Efficiency Improvement 48 Electricity Purchase/Sale Activities 49 Innovation Activity 50 01 ANNUAL REPORT GOAL 4. ECONOMY AND FINANCE 52 Analysis of Financial and Economic Indicators 54 Tariff Policy 58 GOAL 5. MARKET DEVELOPMENT 60 GOAL 6. CORPORATE GOVERNANCE AND SUSTAINABILITY 64 Information on Compliance with the Principles of KEGOC Corporate Governance Code in 2015 66 Shareholders 76 General Shareholders’ Meeting 77 Report on the Board of Directors Activities 2015 77 Management Board 90 Dividend Policy 97 Internal Audit Service (IAS) 99 Risk Management and Internal Control 99 Information Policy 101 HR Policy 102 Environmental Protection 104 Operational Safety 106 Sponsorship and Charity 107 GOAL 7. INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION 108 Collaboration with Power Systems of Other States 110 Professional Association Membership 110 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 112 APPENDICES 182 Appendix 1. Report on Management of Branches and Affiliates, and Impact of the Financial and Economic Performance of Branches and Affiliates, on KEGOC Performance Indicators in 2015 182 Appendix 2. -

The Southern Gas Corridor

Energy July 2013 THE SOUTHERN GAS CORRIDOR The recent decision of The State Oil Company of The EU Energy Security and Solidarity Action Plan the Azerbaijan Republic (SOCAR) and its consortium identified the development of a Southern Gas partners to transport the Shah Deniz gas through Corridor to supply Europe with gas from Caspian Southern Europe via the Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP) and Middle Eastern sources as one of the EU’s is a key milestone in the creation of the Southern “highest energy securities priorities”. Azerbaijan, Gas Corridor. Turkmenistan, Iraq and Mashreq countries (as well as in the longer term, when political conditions This Briefing examines the origins, aims and permit, Uzbekistan and Iran) were identified development of the Southern Gas Corridor, including as partners which the EU would work with to the competing proposals to deliver gas through it. secure commitments for the supply of gas and the construction of the pipelines necessary for its Background development. It was clear from the Action Plan that the EU wanted increased independence from In 2007, driven by political incidents in gas supplier Russia. The EU Commission President José Manuel and transit countries, and the dependence by some Barroso stated that the EU needs “a collective EU Member States on a single gas supplier, the approach to key infrastructure to diversify our European Council agreed a new EU energy and energy supply – pipelines in particular. Today eight environment policy. The policy established a political Member States are reliant on just one supplier for agenda to achieve the Community’s core energy 100% of their gas needs – this is a problem we must objectives of sustainability, competitiveness and address”. -

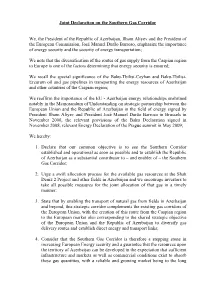

Joint Declaration on the Southern Gas Corridor

Joint Declaration on the Southern Gas Corridor We, the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan, Ilham Aliyev and the President of the European Commission, José Manuel Durão Barroso, emphasize the importance of energy security and the security of energy transportation; We note that the diversification of the routes of gas supply from the Caspian region to Europe is one of the factors determining that energy security is ensured; We recall the special significance of the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan and Baku-Tbilisi- Erzurum oil and gas pipelines in transporting the energy resources of Azerbaijan and other countries of the Caspian region; We reaffirm the importance of the EU - Azerbaijan energy relationships enshrined notably in the Memorandum of Understanding on strategic partnership between the European Union and the Republic of Azerbaijan in the field of energy signed by President Ilham Aliyev and President José Manuel Durão Barroso in Brussels in November 2006, the relevant provisions of the Baku Declaration signed in November 2008, relevant Energy Declaration of the Prague summit in May 2009; We hereby: 1. Declare that our common objective is to see the Southern Corridor established and operational as soon as possible and to establish the Republic of Azerbaijan as a substantial contributor to – and enabler of – the Southern Gas Corridor; 2. Urge a swift allocation process for the available gas resources at the Shah Deniz 2 Project and other fields in Azerbaijan and we encourage investors to take all possible measures for the joint allocation of that gas in a timely manner; 3. State that by enabling the transport of natural gas from fields in Azerbaijan and beyond, this strategic corridor complements the existing gas corridors of the European Union, with the creation of this route from the Caspian region to the European market also corresponding to the shared strategic objective of the European Union and the Republic of Azerbaijan to diversify gas delivery routes and establish direct energy and transport links; 4. -

The Bank of the European Union (Sabine Tissot) the Authors Do Not Accept Responsibility for the 1958-2008 • 1958-2008 • 1958-2008 Translations

The book is published and printed in Luxembourg by 1958-2008 • 1958-2008 • 1958-2008 1958-2008 • 1958-2008 • 1958-2008 15, rue du Commerce – L-1351 Luxembourg 3 (+352) 48 00 22 -1 5 (+352) 49 59 63 1958-2008 • 1958-2008 • 1958-2008 U [email protected] – www.ic.lu The history of the European Investment Bank cannot would thus mobilise capital to promote the cohesion be dissociated from that of the European project of the European area and modernise the economy. 1958-2008 • 1958-2008 • 1958-2008 The EIB yesterday and today itself or from the stages in its implementation. First These initial objectives have not been abandoned. (cover photographs) broached during the inter-war period, the idea of an 1958-2008 • 1958-2008 • 1958-2008 The Bank’s history symbolised by its institution for the financing of major infrastructure in However, today’s EIB is very different from that which 1958-2008 • 1958-2008 • 1958-2008 successive headquarters’ buildings: Europe resurfaced in 1949 at the time of reconstruction started operating in 1958. The Europe of Six has Mont des Arts in Brussels, and the Marshall Plan, when Maurice Petsche proposed become that of Twenty-Seven; the individual national 1958-2008 • 1958-2008 • 1958-2008 Place de Metz and Boulevard Konrad Adenauer the creation of a European investment bank to the economies have given way to the ‘single market’; there (West and East Buildings) in Luxembourg. Organisation for European Economic Cooperation. has been continuous technological progress, whether 1958-2008 • 1958-2008 • 1958-2008 in industry or financial services; and the concerns of The creation of the Bank was finalised during the European citizens have changed. -

Britain, British Petroleum, Shell and the Remaking of the International Oil Industry, 1957-1979

Empires of Energy: Britain, British Petroleum, Shell and the Remaking of the International Oil Industry, 1957-1979 Author: Jonathan Robert Kuiken Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/bc-ir:104079 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2013 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. Boston College The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Department of History EMPIRES OF ENERGY: BRITAIN, BRITISH PETROLEUM, SHELL AND THE REMAKING OF THE INTERNATIONAL OIL INDUSTRY, 1957-1979 [A dissertation by] JONATHAN R. KUIKEN submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August, 2013 © copyright by JONATHAN ROBERT KUIKEN 2013 Empires of Energy: Britain, British Petroleum, Shell and the remaking of the international oil industry, 1957-1979 Jonathan R. Kuiken Dissertation Advisor - James E. Cronin Dissertation Abstract This dissertation examines British oil policy from the aftermath of the Suez Crisis in 1956-1957 until the Iranian Revolution and the electoral victory of Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative Party in 1979. It was a period marked by major transitions within Britain’s oil policy as well as broader changes within the international oil market. It argues that the story of Britain, and Britain’s two domestically-based oil companies, BP and Shell, offers a valuable case study in the development of competing ideas about the reorganization of the international oil industry in the wake of the rise of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting countries and the companies’ losing control over the production of oil. -

Journal of Diplomacy

Seton Hall Journal of Diplomacy and International Relations 400 South Orange Avenue, McQuaid Hall, South Orange, NJ 07079 Tel: 973-275-2515 Fax: 973-275-2519 Email: [email protected] http://www.journalofdiplomacy.org Seton Hall Journal of Diplomacy and International Relations is the official semi- Editor-in-Chief annual publication of the Seton Hall School Dennis Meaney of Diplomacy and International Relations at Seton Hall University. The Journal provides Deputy Editor-in-Chief a unique forum for international leaders in Michael Curtin government, the private sector, academia, and nongovernmental organizations to Executive Editor analyze and comment on international Ruthly Cadestin affairs. Editorial Media Manager Indexing: The Journal is indexed by Sajedeh Goudarzi Columbia International Affairs Online, Public Affairs Information Service, Social Media Associates International Political Science Abstracts, Patricia Zanini Graca, Juan C Garcia, America: History and Life and Historical Abstracts: International Relations and Security Network, and Ulrich’s Periodical Senior Editors Directory. Zehra Khan, Kevin Hill, Chiazam T Onyenso Manuscripts: Address all submissions to the Editor-in-Chief. We accept both hard Associate Editors copies and electronic versions. Submissions Maliheh Bitaraf, Meagan Torello, Erick may not exceed 6,000 words in length and Agbleke, Oluwagbemiga D Oyeneye, Edder must follow the Chicago manual of style. A Zarate, Emanuel Hernandez, Katherine M Submission deadlines are posted on our Landes, Troy L Dorch, Kendra Brock, Alex website. Miller, Devynn N Nolan, Lynn Wassenaar, Morgan McMichen, Eleanor Baldenweck Back Issues: Available upon request. Faculty Adviser Dr. Ann Marie Murphy The opinions expressed in the Journal are those of the contributors and should not be construed as representing those of Seton Hall University, the Seton Hall School of Diplomacy and International Relations, or the editors of the Journal. -

28 January 2016 Werner Hoyer President of the Management

28 January 2016 Werner Hoyer President of the Management Committee, Chairman of the Board of Directors European Investment Bank 100, boulevard Konrad Adenauer L-2950 Luxembourg Object: The EIB should not finance the Southern Gas Corridor Dear President of the European Investment Bank, On behalf of a group of 27 NGOs, we are sending you this letter to express our concerns about the Southern Gas Corridor and to urge the EIB not to finance any section of this project. The EIB is currently considering making the biggest loan of its history (EUR 2 billion) to the Consortium in charge of developing the western section of the corridor, the Trans-Adriatic Pipeline (TAP). In addition, Bloomberg has recently reported that the bank is part of preliminary talks with other multinational institutions for another EUR 2 billion loan to the Turkish state company Botas for the construction of the TANAP, the Turkish section of the Southern Gas Corridor. This comes as no surprise since in February 2015, during the annual meeting between civil society and the EIB Board of Directors, the EIB revealed that the TAP was among its priority projects for 2015 in the Balkans. We urge the EIB not to finance this project for the following reasons: 1/ During the COP21 in Paris, the EIB made numerous announcements about its commitment to tackle the climate crisis and portrayed itself as a leader on climate issues. But if the Southern Gas Corridor does materialiZe and ends up pumping more gas into Europe, the chances of meeting the EU's climate and energy targets for 2030 and its longer term decarbonisation objectives, would hardly be attainable. -

The Southern Gas Corridor the Azerbaijani-Turkish Project Becomes Part of the Game Between Russia and the EU

53 THE SOUTHERN GAS CORRIDOR THE AZERBAIjaNI-TURKISH PROJECT BECOMES PART OF THE GAME BETWEEN RUSSIA AND THE EU Aleksandra Jarosiewicz NUMBER 53 WARSAW AUGUST 2015 THE SOUTHERN GAS CORRIDOR THE AZerbaIJANI-TurKISH PROJECT beCOmes Part OF THE game between RussIA anD THE EU Aleksandra Jarosiewicz © Copyright by Ośrodek Studiów Wschodnich im. Marka Karpia / Centre for Eastern Studies Content editors Olaf Osica, Krzysztof Strachota, Adam Eberhardt Editor Halina Kowalczyk, Anna Łabuszewska Translation Ilona Duchnowicz Co-operation Timothy Harrell Graphic design PARA-BUCH DTP GroupMedia MAP Wojciech Mańkowski Photograph on cover Shutterstock The author would like to thank International Research Networks for making it possible for her to participate in the Turkey Oil and Gas Submit conference in 2014. PUBLISHER Ośrodek Studiów Wschodnich im. Marka Karpia Centre for Eastern Studies ul. Koszykowa 6a, Warsaw, Poland Phone + 48 /22/ 525 80 00 Fax: + 48 /22/ 525 80 40 osw.waw.pl ISBN 978-83-62936-75-5 Contents THESES /5 INTRODUCTION /7 I. THE genesIS anD THE EVOLutION OF THE EU’S SOutHern Gas CORRIDOR CONCEPT /9 II. THE COrrIDOR TODAY: new INFrastruCture Owners anD new RULes OF OPeratION /13 III. THE SIgnIFICANCE OF THE SOutHern Gas CORRIDOR FOR THE energY seCTOR /17 1. Azerbaijan – the life line /17 2. Turkey – TANAP as a stage in the construction of a gas hub /19 3. The EU – a drop in the ocean of needs /20 IV. UKraIne Casts A SHADOW OVer THE SOutHern Gas CORRIDOR /22 1. Turkish Stream instead of South Stream – the Russian gas gambit /23 2. The EU’s interest in the Southern Gas Corridor – no implementation instruments /27 V. -

Energy Diplomacy Beyond Pipelines: Navigating Risks and Opportunities

REPORT December 2020 ENERGY DIPLOMACY BEYOND PIPELINES: NAVIGATING RISKS AND OPPORTUNITIES PIETER DE POUS, LISA FISCHER & FELIX HEILMANN About E3G Copyright E3G is an independent climate change think This work is licensed under the Creative tank accelerating the transition to a climate Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- safe world. E3G builds cross-sectoral coalitions ShareAlike 2.0 License. to achieve carefully defined outcomes, chosen for their capacity to leverage change. You are free to: E3G works closely with like-minded partners > Copy, distribute, display, and perform in government, politics, business, civil the work. society, science, the media, public interest foundations and elsewhere. > Make derivative works. www.e3g.org Under the following conditions: Berlin > You must attribute the work in the Neue Promenade 6 manner specified by the author Berlin, 10178 or licensor. Germany +49 (0)30 2887 3405 > You may not use this work for commercial purposes. Brussels Rue du Commerce 124 > If you alter, transform, or build upon Brussels, 1000 this work, you may distribute the Belgium resulting work only under a license +32 (0)2 5800 737 identical to this one. > For any reuse or distribution, London you must make clear to others the license 47 Great Guildford Street terms of this work. London SE1 0ES United Kingdom > Any of these conditions can be waived +44 (0)20 7593 2020 if you get permission from the copyright holder. Washington 2101 L St NW Your fair use and other rights are Suite 400 in no way affected by the above. Washington DC, 20037 United States +1 202 466 0573 © E3G 2020 Cover image Photo by qimono on Pixabay 2 ENERGY DIPLOMACY CHOICE S : NAV IGATING R I S K S A N D OPPORTUNITIES REPORT DECEMBER 2020 ENERGY DIPLOMACY BEYOND PIPELINES: NAVIGATING RISKS AND OPPORTUNITIES PIETER DE POUS, FELIX HEILMANN & LISA FISCHER 3 ENERGY DIPLOMACY CHOICE S : NAV IGATING R I S K S A N D OPPORTUNITIES Acknowledgements This project has received funding from the European Commission through a LIFE grant. -

OPEC and the International System: a Political History of Decisions and Behavior Reza Sanati Florida International University, [email protected]

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 3-24-2014 OPEC and the International System: A Political History of Decisions and Behavior Reza Sanati Florida International University, [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FI14040875 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the International Relations Commons Recommended Citation Sanati, Reza, "OPEC and the International System: A Political History of Decisions and Behavior" (2014). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1149. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/1149 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida OPEC AND THE INTERNATIONAL SYSTEM: A POLITICAL HISTORY OF DECISIONS AND BEHAVIOR A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS by Reza Sanati 2014 To: Dean Kenneth G. Furton College of Arts and Sciences This dissertation, written by Reza Sanati, and entitled OPEC and the International System: A Political History of Decisions and Behavior, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this dissertation and recommend that it be approved. _______________________________________ Thomas Breslin _______________________________________ Mira Wilkins _______________________________________ Ronald Cox _______________________________________ Mohiaddin Mesbahi, Major Professor Date of Defense: March 24, 2014 The dissertation of Reza Sanati is approved.