World War One in Long Crendon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

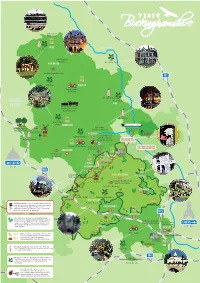

Buckinghamshire Attractions

Silverstone Race Track Stowe Milton Keynes Stowe Buckingham Old Gaol Buckingham Bletchley Park Buckingham Brewery M1 Claydon winslow Green Dragon Eco Farm Aylesbury Vale Bicester Ascot House village Wing Buckinghamshire Railway Centre Mentmore Waddesdon Manor Waddesdon Aylesbury Bernwood Royal Grebe Canal Waterside Theatre Hunting Forest Cruises Vale Brewery Aylesbury Ashridge County Museum Brill Hartwell House and Roald Dahl Magnolia Park Children’s Gallery Ickneild way Orchard View Farm Stoke Mandeville Grand union Canal Haddenham Guttman Centre XT Brewing The Chiltern Company Wendover Brewery OXFORD Princes Coombe Hill Risborough M40 Whiteleaf Chinnor and Princes Great missenden Risborough Railway chesham Lacey Green Roald Dahl Museum and Story Centre Malt The Brewery Amersham Red Kite viewing point Hughenden Manor west wycombe Buckinghamshire is one of the most filmed counties Hellfire Caves with blockbuster such Harry Potter and James Bond, The Artichoke together with the popular television series high wycombe Midsummer Murders using it’s scenic countryside and historic buildings as backdrops. M25 beaconsfield The Chilterns is an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty ideal for walkers and bikers and an excellent Bekonscot Model viewpoint to spot Redkites. It’s the only AONB that The Rebellion Chiltern Open can be reached by the London Underground, is the Beer Company Village and Railway London 4th largest in the UK and has over 12,000 miles of Air Museum walks within it. Marlow denham The Hand Odds Farm With a thriving community of independent and Flowers food and drink providers, farmers markets Buckinghamshire and Michellin Starred restaurants, Buckinghamshire is a food lovers heaven. Stoke Park Iver Buckinghamshire has more golf courses than any other county in England. -

16.0 Management/Restoration of Particular Features

AYLESBURY VALE DISTRICT COUNCIL Conservation Area Management Plan – District Wide Strategy 16.0 Management/restoration of particular features 16.1 Aims 16.2 Issues for Aylesbury Vale in relation to the management/restoration of particular I Clearly identify those features (such as traditional features street signage for example) which make a positive contribution to the character and appearance of the 16.2.1 There are three groups of features that stand out conservation area in the appraisal from analysis of the sample survey and through I Produce information leaflets on the importance of consultation with local groups and development certain features including why they are important control. These are: and general advice on their care and management – these should be distributed to every household within I Shopfronts the conservation area(s) subject to available I Boundary walls resources I Traditional paving materials I Build a case (based on the thorough analysis of the conservation area) for a grant fund to be established 16.2.2 Shopfronts are strongly represented in identifying the particular feature for repair and Aylesbury and Buckingham (and Winslow and reinstatement Wendover outside the sample survey) and despite a I Seek regional or local sponsorship of a scheme for good shopfront design guide, the issues of poor quality, the reinstatement of particular features such as badly designed shopfronts, inappropriate materials for shopfronts fascias and poor colour schemes and lighting design I Consultation with grant providers such as English are still significant issues in these market towns. Heritage and the Heritage Lottery Fund should establish at an early stage the potential success of an 16.2.3 Boundary walls are a district-wide issue and are application and identify a stream of funding for also a Buildings at Risk issue throughout the district. -

Views of the Vale Walks.Cdr

About the walk Just a 45 minute train ride from London Marylebone and a few minutes walk from Wendover station you can enjoy the fresh air and fantastic views of the Chilterns countryside. These two walks take you to the top of the Chiltern Hills, through ancient beech woods, carpets of bluebells and wild flowers. There are amazing views of the Aylesbury Vale and Chequers, the Prime Minister's country home. You might also see rare birds such as red kites and firecrests and the tiny muntjac deer. 7 Wendover Woods – this is the habitat of the rare Firecrest, the smallest bird in Europe, which nests in the Norway spruce. You can finish your walk with a tasty meal, pint of beer or a This is also the highest point in the Chilterns (265m). The cup of tea. woods are managed by Forest Enterprise who have kindly granted access to those trails that are not public rights of way. Walking gets you fit and keeps you healthy!! 8 Boddington hillfort. This important archaeological site was occupied during the 1st century BC. Situated on top of the hill, the fort would have provided an excellent vantage point and defensive position for its Iron Age inhabitants. In the past the hill was cleared of trees for grazing animals. Finds have included a bronze dagger, pottery and a flint scraper. 9 Coldharbour cottages – were part of Anne Boleyn's dowry to Henry VIII. 4 Low Scrubs. This area of woodland is special and has a 10 Red Lion Pub – built in around 1620. -

LCA 10.2 Ivinghoe Foothills Landscape Character Type

Aylesbury Vale District Council & Buckinghamshire County Council Aylesbury Vale Landscape Character Assessment LCA 10.2 Ivinghoe Foothills Landscape Character Type: LCT 10 Chalk Foothills B0404200/LAND/01 Aylesbury Vale District Council & Buckinghamshire County Council Aylesbury Vale Landscape Character Assessment LCA 10.2 Ivinghoe Foothills (LCT 10) Key Characteristics Location An extensive area of land which surrounds the Ivinghoe Beacon including the chalk pit at Pitstone Hill to the west and the Hemel Hempstead • Chalk foothills Gap to the east. The eastern and western boundaries are determined by the • Steep sided dry valleys County boundary with Hertfordshire. • Chalk outliers • Large open arable fields Landscape character The LCA comprises chalk foothills including dry • Network of local roads valleys and lower slopes below the chalk scarp. Also included is part of the • Scattering of small former chalk pits at Pitstone and at Ivinghoe Aston. The landscape is one of parcels of scrub gently rounded chalk hills with scrub woodland on steeper slopes, and woodland predominantly pastoral use elsewhere with some arable on flatter slopes to • Long distance views the east. At Dagnall the A4146 follows the gap cut into the Chilterns scarp. over the vale The LCA is generally sparsely settled other than at the Dagnall Gap. The area is crossed by the Ridgeway long distance footpath (to the west). The • Smaller parcels of steep sided valley at Coombe Hole has been eroded by spring. grazing land adjacent to settlements Geology The foothills are made up of three layers of chalk. The west Melbury marly chalk overlain by a narrow layer of Melbourn Rock which in turn is overlain by Middle Chalk. -

Buckinghamshire Historic Town Project

Long Crendon Historic Town Assessment Consultation Report 1 Appendix: Chronology & Glossary of Terms 1.1 Chronology (taken from Unlocking Buckinghamshire’s Past Website) For the purposes of this study the period divisions correspond to those used by the Buckinghamshire and Milton Keynes Historic Environment Records. Broad Period Chronology Specific periods 10,000 BC – Palaeolithic Pre 10,000 BC AD 43 Mesolithic 10,000 – 4000 BC Prehistoric Neolithic 4000 – 2350 BC Bronze Age 2350 – 700 BC Iron Age 700 BC – AD 43 AD 43 – AD Roman Expedition by Julius Caesar 55 BC Roman 410 Saxon AD 410 – 1066 First recorded Viking raids AD 789 1066 – 1536 Battle of Hastings – Norman Conquest 1066 Wars of the Roses – Start of Tudor period 1485 Medieval Built Environment: Medieval Pre 1536 1536 – 1800 Dissolution of the Monasteries 1536 and 1539 Civil War 1642-1651 Post Medieval Built Environment: Post Medieval 1536-1850 Built Environment: Later Post Medieval 1700-1850 1800 - Present Victorian Period 1837-1901 World War I 1914-1918 World War II 1939-1945 Cold War 1946-1989 Modern Built Environment: Early Modern 1850-1945 Built Environment: Post War period 1945-1980 Built Environment: Late modern-21st Century Post 1980 1.2 Abbreviations Used BGS British Geological Survey EH English Heritage GIS Geographic Information Systems HER Historic Environment Record OD Ordnance Datum OS Ordnance Survey 1.3 Glossary of Terms Terms Definition Building Assessment of the structure of a building recording Capital Main house of an estate, normally the house in which the owner of the estate lived or Messuage regularly visited Deer Park area of land approximately 120 acres or larger in size that was enclosed either by a wall or more often by an embankment or park pale and were exclusively used for hunting deer. -

110 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

110 bus time schedule & line map 110 Aylesbury - Long Crendon - Thame - Worminghall View In Website Mode The 110 bus line (Aylesbury - Long Crendon - Thame - Worminghall) has 4 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Aylesbury: 9:07 AM - 4:59 PM (2) Ickford: 10:15 AM - 12:15 PM (3) Thame: 7:38 AM - 2:20 PM (4) Worminghall: 8:25 AM - 12:25 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 110 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 110 bus arriving. Direction: Aylesbury 110 bus Time Schedule 40 stops Aylesbury Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 9:07 AM - 4:59 PM The Avenue, Worminghall Tuesday 9:07 AM - 4:59 PM The Rising Sun Ph, Ickford Worminghall Road, Ickford Civil Parish Wednesday 9:07 AM - 4:59 PM Primary School, Ickford Thursday 9:07 AM - 4:59 PM Friday 9:07 AM - 4:59 PM Bulls Lane, Ickford Saturday 9:17 AM - 1:17 PM Ickford Road, Shabbington Ickford Road, Shabbington Civil Parish Home Close, Shabbington 110 bus Info Carters Lane, Long Crendon Direction: Aylesbury Stops: 40 Bonnersƒeld, Long Crendon Trip Duration: 63 min Line Summary: The Avenue, Worminghall, The Rising The Square, Long Crendon Sun Ph, Ickford, Primary School, Ickford, Bulls Lane, Ickford, Ickford Road, Shabbington, Home Close, The Square, Long Crendon Shabbington, Carters Lane, Long Crendon, Thame Road, Long Crendon Bonnersƒeld, Long Crendon, The Square, Long Crendon, Thame Road, Long Crendon, Southƒeld, Southƒeld, Long Crendon Long Crendon, Queens Close, Thame, Cricket Ground, Thame, North Street, Thame, Town -

BUCKING HAMS HIRE. [KBLLY's

46 LITTLR BRICKHILL. BUCKING HAMS HIRE. [KBLLY's 2Jth, r644. There is a record of the vicars of this Duke of Buckingham, killed a.t Northampton, 27 July, parish from the year 1'227 to r8go. The living is a 1460, Sir Henry Marney kt. 1st baron Marney, d. 24 titular vicarage, net yearly value £r6o, in the gift May, 1523, William Carey, Sir Thomas Neville Abdy of the Bishop of Oxford, and held since 1906 by the hart. d. 20 July, r877, Sir Charles Duncombe kt. d. Rev. Louis J ones B. A. of Christ's College, Cambridge. 17II, Sir William Rose, Lord Strathnairn and Admiral This village was formerly the first place in the county at Douglas. The manorial rights have ceased; the wb.ich the judges arrived on going the Norfolk circuit, present owner of the manor is Lieut.-Col. Alexander and from 1433 to r638 the a.ssizes and genexal gaol Finlay. The Duke of Bedford K.G. and Sir Ever<J,rd deliveries for Bucks were held here on aooount of its P. D. Pauncefort-Duncombe hart. of Brickhill Manor, beirug the nearsst spot in Buck..s to the metropolis, with also have property in the parish. The situation of this a good road and accommodation for man and horse ; in village on the highest part of the Brickhills Cfr. Saxton's map af 1574, it is marked as an assize town, Briehelle) and adjoining the Woburn plantations is and election as well at~ othsr county meetings were a.l!ro picturesque and eminently healthy. -

Aylesbury Vale Community Chest Grants April 2014 - March 2015

Aylesbury Vale Community Chest Grants April 2014 - March 2015 Amount Granted Total Cost Award Aylesbury Vale Ward Name of Organisation £ £ Date Purpose Area Buckinghamshire County Local Areas Artfully Reliable Theatre Society 1,000 1,039 Sep-14 Keyboard for rehearsals and performances Aston Clinton Wendover Aylesbury & District Table Tennis League 900 2,012 Sep-14 Wall coverings and additional tables Quarrendon Greater Aylesbury Aylesbury Astronomical Society 900 3,264 Aug-14 new telescope mount to enable more community open events and astrophotography Waddesdon Waddesdon/Haddenham Aylesbury Youth Action 900 2,153 Jul-14 Vtrek - youth volunteering from Buckingham to Aylesbury, August 2014 Vale West Buckingham/Waddesdon Bearbrook Running Club 900 1,015 Mar-15 Training and raceday equipment Mandeville & Elm Farm Greater Aylesbury Bierton with Broughton Parish Council 850 1,411 Aug-14 New goalposts and goal mouth repairs Bierton Greater Aylesbury Brill Memorial Hall 1,000 6,000 Aug-14 New internal and external doors to improve insulation, fire safety and security Brill Haddenham and Long Crendon Buckingham and District Mencap 900 2,700 Feb-15 Social evenings and trip to Buckingham Town Pantomime Luffield Abbey Buckingham Buckingham Town Cricket Club 900 1,000 Feb-15 Cricket equipment for junior section Buckingham South Buckingham Buckland and Aston Clinton Cricket Club 700 764 Jun-14 Replacement netting for existing practice net frames Aston Clinton Wendover Bucks Play Association 955 6,500 Apr-14 Under 5s area at Play in The Park event -

40 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

40 bus time schedule & line map 40 High Wycombe View In Website Mode The 40 bus line (High Wycombe) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) High Wycombe: 6:30 AM - 8:35 PM (2) Thame: 6:15 AM - 8:35 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 40 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 40 bus arriving. Direction: High Wycombe 40 bus Time Schedule 46 stops High Wycombe Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 8:45 AM - 6:35 PM Monday 6:30 AM - 8:35 PM Town Hall, Thame 1 High Street, Thame Tuesday 6:30 AM - 8:35 PM Health Centre, Thame Wednesday 6:30 AM - 8:35 PM Orchard Close, Thame Thursday 6:30 AM - 8:35 PM Churchill Crescent, Thame Friday 6:30 AM - 8:35 PM Windmill Road, Towersey Saturday 7:38 AM - 8:35 PM Thame Road, Towersey Civil Parish Village Hall, Towersey Waterlands Farm, Emmington 40 bus Info Direction: High Wycombe The Inn at Emmington, Sydenham Stops: 46 Thame Road, Chinnor Civil Parish Trip Duration: 54 min Line Summary: Town Hall, Thame, Health Centre, Thame Road Shops, Chinnor Thame, Churchill Crescent, Thame, Windmill Road, Towersey, Village Hall, Towersey, Waterlands Farm, Springƒeld Gardens, Chinnor Emmington, The Inn at Emmington, Sydenham, Lower Road, Chinnor Thame Road Shops, Chinnor, Springƒeld Gardens, Chinnor, The Red Lion, Chinnor, The Village Centre, The Red Lion, Chinnor Chinnor, Village Hall, Chinnor, Glynswood, Chinnor, Chiltern Hill Garage, Chinnor, Glimbers Green, The Village Centre, Chinnor Chinnor, St Marys Church, Crowell, The Cherry Tree, Kingston Blount, Village Turn, -

Meeting with Warwickshire County Council

Summary of changes to subsidised services in the Wheatley, Thame & Watlington area Effective from SUNDAY 5th June 2011 ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………... Line 40:- High Wycombe – Chinnor – Thame Broadly hourly service maintained, operated by Arriva the Shires. Only certain journeys will serve Towersey village, but Towersey will also be served by routes 120 and 123 (see below). Service 101:- Oxford – Garsington – Watlington A broadly hourly service maintained, operated by Thames Travel Monday to Saturday between Oxford City Centre and Garsington. Certain peak buses only will start from or continue to Chalgrove and Watlington, this section otherwise will be served by route 106 (see below). Service 101 will no longer serve Littlehay Road or Rymers Lane, or the Cowley Centre (Nelson) stops. Nearest stops will be at the Original Swan. Service 102:- Oxford – Horspath – Watlington This Friday and Saturday evening service to/from Oxford City is WITHDRAWN. Associated commercial evening journeys currently provided on route 101 by Thames Travel will also be discontinued. Service 103:- Oxford – Horspath – Wheatley – Great Milton - Little Milton Service 104:- Oxford – Horspath – Wheatley – Great Milton – Cuddesdon /Denton A broadly hourly service over the Oxford – Great Milton section will continue to be operated by Heyfordian Travel Mondays to Saturdays. Buses will then serve either Little Milton (via the Haseleys) or Cuddesdon / Denton alternately every two hours as now. The route followed by service 104 will be amended in the Great Milton area and the section of route from Denton to Garsington is discontinued. Routes 103 and 104 will continue to serve Littlehay Road and Rymers Lane and Cowley (Nelson) stops. Service 113 is withdrawn (see below). -

Het Verwyderde Amerika!

Geraardsbergse sigarenmakers trekken massaal naar ''HE T VERWYDERDE AMERIKA!" Dirck SURDLACOURT Eind negentiende maar vooral begin twintigste eeuw, tot de Eerste We reldoorlog, kent Geraardsbergen een opvallend grote arbeidsmigratie naar Amerika. Honderden sigarenmakers trekken naar Boston en omgeving om daar 'grofgeld' te verdienen in de sigarennijverheid. Wa arom trekken de Geraardsbergse sigarenmakers naar het 'verwyderde' Amerika? Een eerste onderzoeksresultaat." De jaren van de 'Argentijnse koorts' migratie onder de sigarenmakers. is het ook daar niet altijd rozegeur Zo zien we de eerste vormen van ar en maneschijn. Zo zorgt de financi In een van de eerste teruggevonden beidsmigratie in de naweeën van de ele crisis in 1907, de zogeheten Panic artikelen over landverhuizers in het werkstaking van de Geraardsbergse of 1907, ervoor dat in 1908 heel wat arrondissement Aalst, wijdt het Land sigarenmakers in 1879-1880. Een stadsgenoten uit Amerika terugke van Aelst in januari 1889 een uitge twintigtal arbeiders trekt - uit on ren. De situatie is onduidelijk. Men breid artikel aan de opkomende mi genoegen met de lokale situatie - in begrijpt het hier allemaal niet. De gratiegolf naar Amerika: "Vele Belgen 1880 naar Duitsland. In 1881 beslist Aalsterse krant De Denderbode roept zijn tegenwoordig gedwongen hun be het sigarenverbond van Antwerpen, het werkvolk op om in België te staan in andere Landen te gaan zoeken." waarbij ook de Geraardsbergse si blijven en niet te emigreren: "Er is De opsteller van deze tekst raadt de garenmakers zijn aangesloten, om tegenwoordig eene ziekte onder de kleine mensen aan twee keer na te denken leden geldelijk te steunen die naar boeren en 't werkvolk uitgebroken, en vooraleer de stap te zetten: "Onze Amerika, Londen of Duitsland wil wel namelijk die van te wille vertrekken Landgenoten dienen eerst na te zien of len gaan werken. -

For Enquiries on This Agenda Please Contact

Incorporating the parishes of : Ashendon WADDESDON LOCAL AREA FORUM Dorton Edgcott Fleet Marston Grendon Underwood Kingswood DATE: 3 December 2019 Ludgershall TIME: 7.00 pm Marsh Gibbon Nether Winchendon Calvert Green Village Quainton VENUE: Hall Upper Winchendon Waddesdon Westcott Woodham Wotton Underwood PARISH / TOWN COUNCIL DROP-IN FROM 6.30pm Come along to the drop-in and speak to your local representative from Transport for Buckinghamshire who will be on hand to answer your questions. AGENDA Item Page No 1 Apologies for Absence / Changes in Membership 2 Declarations of Interest To disclose any Personal or Disclosable Pecuniary Interests 3 Action Notes 3 - 8 To confirm the notes of the meeting held on 2 October 2019. 4 Question Time There will be a 20 minute period for public questions. Members of the public are encouraged to submit their questions in advance of the meeting to facilitate a full answer on the day of the meeting. Questions sent in advance will be dealt with first and verbal questions after. 5 Petitions None received 6 The Chairmans Update 7 Youth Project Update Update from the Youth Project group. 8 Climate Change Presentation from the Local Area Forum Officer. 9 Transport for Bucks Update 9 - 32 10 Thames Valley Neighbourhood Police Update 11 Street Association Presentation from Ms H Cavill, Street Association Project Manager. Visit democracy.buckscc.gov.uk for councillor information and email alerts for meetings, and decisions affecting your local area. 12 Unitary Update 33 - 38 Update from the Lead Area Officer, BCC. 13 AVDC Update 39 - 46 Update from Mr W Rysdale, AVDC.