Juneteenth: Fact Sheet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

STANDING COMMITTEES of the HOUSE Agriculture

STANDING COMMITTEES OF THE HOUSE [Democrats in roman; Republicans in italic; Resident Commissioner and Delegates in boldface] [Room numbers beginning with H are in the Capitol, with CHOB in the Cannon House Office Building, with LHOB in the Longworth House Office Building, with RHOB in the Rayburn House Office Building, with H1 in O’Neill House Office Building, and with H2 in the Ford House Office Building] Agriculture 1301 Longworth House Office Building, phone 225–2171, fax 225–8510 http://agriculture.house.gov meets first Wednesday of each month Collin C. Peterson, of Minnesota, Chair Tim Holden, of Pennsylvania. Bob Goodlatte, of Virginia. Mike McIntyre, of North Carolina. Terry Everett, of Alabama. Bob Etheridge, of North Carolina. Frank D. Lucas, of Oklahoma. Leonard L. Boswell, of Iowa. Jerry Moran, of Kansas. Joe Baca, of California. Robin Hayes, of North Carolina. Dennis A. Cardoza, of California. Timothy V. Johnson, of Illinois. David Scott, of Georgia. Sam Graves, of Missouri. Jim Marshall, of Georgia. Jo Bonner, of Alabama. Stephanie Herseth Sandlin, of South Dakota. Mike Rogers, of Alabama. Henry Cuellar, of Texas. Steve King, of Iowa. Jim Costa, of California. Marilyn N. Musgrave, of Colorado. John T. Salazar, of Colorado. Randy Neugebauer, of Texas. Brad Ellsworth, of Indiana. Charles W. Boustany, Jr., of Louisiana. Nancy E. Boyda, of Kansas. John R. ‘‘Randy’’ Kuhl, Jr., of New York. Zachary T. Space, of Ohio. Virginia Foxx, of North Carolina. Timothy J. Walz, of Minnesota. K. Michael Conaway, of Texas. Kirsten E. Gillibrand, of New York. Jeff Fortenberry, of Nebraska. Steve Kagen, of Wisconsin. Jean Schmidt, of Ohio. -

TLTA Attends Federal Affairs Conference in DC

TLTA Attends Federal Affairs Conference in DC Left to Right: Craig Brown; Randy Pitman, past TLTA president - West Texas Abstract & Title Co.; Dawn Moore, TLTA president - Allegiance Title Company; Phyllis Mulder, past TLTA president – Alliant National Title Insurance; Cheryl Cox – TitleClose, Inc.; Jack Rattikin III, past TLTA president – Rattikin Title Company. Last week, a delegation of TLTA members and past presidents led by President Dawn Moore, visited Washington, D.C. as part of the American Land Title Association Federal Affairs Conference. Over the course of a day and a half, the group held sixteen different face-to-face meetings with members and staff of the U.S. Congress to discuss the CFPB and their TRID implementation set to begin August 1, 2015. The group met personally with Senator John Cornyn and Chairman of the House Financial Services Committee, Jeb Hensarling (R-Dallas), as well as, Pete Sessions (R-Dallas); Bill Flores (R-Waco); Marc Veasey (D-Ft. Worth); Ruben Hinojosa (D-Beeville); Roger Williams (R- Austin); Kenny Marchant (RIrving); Pete Olson (R-Sugar Land); and, two new freshman Members from Texas, John Ratcliffe (RRockwall) and Dr. Brian Babin (R-Woodville). In addition, they met with staff of Senator Ted Cruz, Congressman Randy Neugebauer (R- Lubbock), Al Green (D-Houston); Mike Conaway (R-Midland) and freshman Will Hurd (R-San Antonio). The group specifically asked the elected officials to considering supporting a move to get CFPB to institute a “hold harmless” or “restrained enforcement” period for the first five months the TRID rule is in effect. There is legislation in Congress, HR 2213, to require CFPB to not enforce good faith mistakes on the new disclosures until after December 31, 2015. -

OMSA 2019 Auction Catalog

! OMSA AUCTION 2019 The Woodlands Waterway Marriott Hotel & Convention Center 1601 Lake Robbins Drive The Woodlands, TX 77380 Thursday, August 15, 2019 Pre-Sale Viewing – 5:45 pm Auction – 6:45 pm AUCTION RULES Primary Rule The first and foremost rule of this auction is to HAVE FUN! Bid High and Bid Often All proceeds from the sale benefit YOUR Society and will go to the OMSA General Fund, to be specifically used for the direct benefit of members, such as for research grants, publications and/or future convention enhancements. This is a Live Auction Only Only those OMSA members registered for the 2019 Convention may bid in the sale. Buyers must be physically present at the auction and must use the numbered bidder card assigned to them during the Convention registration process. No Buyer’s Premium If the lot is knocked down to you, what you bid is what you pay. All Items Sold to the Highest Bidder The Auctioneer has the sole discretion to conduct the sale and determine the highest bidder. In the event of any dispute, his decision will be final. Everything is sold “As is, Where is” Although all lots have been described in good faith, there are no guarantees as to description accuracy, item authenticity or condition. Once lots are sold there will be no refunds or returns, therefore all items should be physically inspected prior to the sale. Payment and Collection No lots will be released the night of the sale, but rather must be paid for and collected on Friday morning at the Convention Registration Tables between 9 a.m. -

200 E. Commerce Jacksonville, Texas 75766 903-586-1526 903-541-2086 Fax

Austin Bank October 3, 2012 Federal Reserve Board RE: Basel III Docket No. 1442 Ladies and Gentlemen: I am writing to oppose the new proposed Basel III standards. I am also asking that community banks be exempt. Frankly, the whole proposal should be examined for the unintended consequences. I feel the Basel III Proposal will cause an artificial credit crunch in our area and around the country, here is why: In Cherokee County, where we are domiciled, the average home purchased/for sale is $120,000. Right now, our bank could potentially make $1 billion in 1-4 multi-family mortgage loans with existing risk weights. Let's take a look at the impact: If the risk rating = 50%, $1 billion ÷ $120,000 = 8,333 loans made If the risk rating = 100%, $1 billion ÷ $120,000 = 4,167 loans - a reduction of 4,166 loans And if, the rating = 200%, as proposed, $1 billion ÷ 2,083 loans! - a reduction of 6.250 loans Our banks will lose the ability to make loans and our capital would be drastically reduced. With Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae out of the equation, this will further lead to a "rationing of loans" I am asking you to delay or suspend the new rules associated with the Basel III Proposal. Our industry depends on your support - so do the millions of consumers across the country. Please do not hamper community banks from doing what they do best - making loans in their communities. Respectfully.signed. Jeff Austin, III Vice Chairman CC: Eric Sandberg, Texas Bankers Association Frank Keating, American Bankers Association Congressman Jeb Hensarling Congressman Louie Gohmert Congressman Randy Neugebauer Senator Kay Bailey Hutchison Senator John Cornyn 200 E. -

A Resolution Supporting the Designation of Juneteenth and Indigenous People’S Day Official University Observances

A Resolution Supporting the Designation of Juneteenth and Indigenous People’s Day Official University Observances Presented on the 20th of August 2020 Sponsors: Kamali Clora, Isabella Warmbrunn, Jasmine Coles Co-Sponsors: Rajan Varmon, Marcus Meade, Riya Chhabra WHEREAS, effective January 1, 1863, “all persons held as slaves” were to be freed under the Emancipation Proclamation, in which word of this proclamation did not reach Texas until two and a half years later, on June 19, 1865, AND WHEREAS, a blend of “June” and “nineteenth,” Juneteenth commemorates the day that news of emancipation and the end of the Civil War reached enslaved people in Galveston, Texas when federal troops arrived led by U.S. General Gordon Granger, AND WHEREAS, Juneteenth is the oldest known celebration honoring the end of slavery in the United States and is a reminder that nobody is free until everyone is free, AND WHEREAS, the idea of Indigenous Peoples Day was first proposed in 1977 by a delegation of Native Nations to the United Nations-sponsored International Conference on Discrimination Against Indigenous Populations in the Americas, AND WHEREAS, Indigenous People's Day began as a counter-celebration to Columbus Day, due to Christopher Columbus's violent colonization of Native Americans, AND WHEREAS, Indigenous people’s day is celebrated on the second Monday of October honoring the history and culture of the Native American community, while revealing historical truths about the genocide and oppression of indigenous peoples in the Americas,1 AND WHEREAS, Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer issued proclamations declaring June 19th as Juneteenth Celebration Day and the second Monday of October Indigenous People's Day,2 3AND 1 https://www.newsweek.com/columbus-day-replace-indigenous-peoples-day-college-students-poll-1463610 2 https://www.michigan.gov/whitmer/0,9309,7-387-90499_90639-499777--,00.html 3 https://www.michigan.gov/whitmer/0,9309,7-387-90499_90639-509813-- ,00.html#:~:text=NOW%2C%20THEREFORE%2C%20I%2C%20Gretchen,roots%2C%20history%2C%20and%20contri butions. -

Jess' Indix Updates

Volume XXXI, Issue 4 Sherman in North Georgia: The Battle of Resaca, by Stephen Davis Wiley Sword’s War Letters Series—Lt. Nathaniel Howard Talbot, 58th Massachusetts Vol. Inf., Describes In Breathless Detail the Final Major Battle at Petersburg, Va.—The Union Assault on Fort Mahone Driving Tour—The Battle of Resaca, by Dave Roth, with Ken Padgett, President, Friends of Resaca Battlefield Book Reviews: Lincoln’s Citadel: The Civil War in Washington, D.C., by Kenneth J. Winkle. Reviewed by Ethan S. Rafuse. The Dunning School: Historians, Race, and the Meaning of Reconstruction, by John D. Smith. Reviewed by Richard M. McMurry. The Smell of Battle, The Taste of Siege—A Sensory History of the Civil War, by Mark M. Smith. Reviewed Tom Elmore. The Scorpion’s Sting: Antislavery and the Coming of the Civil War, by James Oakes. Reviewed by Jonathan Newell. The Fighting Fifteenth Alabama Infantry—A Civil War History and Roster, by James P. Faust. Reviewed by Justin Mayhue. The Appomattox Generals: The Parallel Lives of Joshua L. Chamberlain, USA, and, and John B. Gordon, CSA, Commanders at the Surrender Ceremony April 12, 1865, by John W. Primomo. Reviewed by David Marshall. “The Devil’s to Pay”: John Buford at Gettysburg, by Eric J. Wittenburg. Reviewed by Robert Grandchamp. Volume XXXI, Issue 3 From Sailor’s Creek to Cumberland Church, April 6-7, 1865: Seventy-Two Hours Before Appomattox, by Chris Calkins Driving Tour—Lee’s Retreat Toward Appomattox, April 3-7, 1865, by Dave Roth, with Chris Calkins Book Reviews: A Gunner in Lee’s Army: The Civil War Letters of Thomas Henry Carter, by Graham T. -

Chapter One: the Campaign for Chattanooga, June to November 1863

CHAPTER ONE: THE CAMPAIGN FOR CHATTANOOGA, JUNE TO NOVEMBER 1863 Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park commemorates and preserves the sites of important and bloody contests fought in the fall of 1863. A key prize in the fighting was Chattanooga, Tennessee, an important transportation hub and the gateway to Georgia and Alabama. In the Battle of Chickamauga (September 18-20, 1863), the Confederate Army of Tennessee soundly beat the Federal Army of the Cumberland and sent it in full retreat back to Chattanooga. After a brief siege, the reinforced Federals broke the Confeder- ate grip on the city in a series of engagements, known collectively as the Battles for Chatta- nooga. In action at Brown’s Ferry, Wauhatchie, and Lookout Mountain, Union forces eased the pressure on the city. Then, on November 25, 1863, Federal troops achieved an unex- pected breakthrough at Missionary Ridge just southeast of Chattanooga, forcing the Con- federates to fall back on Dalton, Georgia, and paving the way for General William T. Sherman’s advance into Georgia in the spring of 1864. These battles having been the sub- ject of exhaustive study, this context contains only the information needed to evaluate sur- viving historic structures in the park. Following the Battle of Stones River (December 31, 1862-January 2, 1863), the Federal Army of the Cumberland, commanded by Major General William S. Rosecrans, spent five and one-half months at Murfreesboro, Tennessee, reorganizing and resupplying in preparation for a further advance into Tennessee (Figure 2). General Braxton Bragg’s Confederate Army of Tennessee was concentrated in the Tullahoma, Tennessee, area. -

Legislative Resolution 351

LR351 LR351 ONE HUNDRED SECOND LEGISLATURE FIRST SESSION LEGISLATIVE RESOLUTION 351 Introduced by Council, 11; Cook, 13. WHEREAS, for more than 130 years, Juneteenth National Freedom Day has been the oldest and only African-American holiday observed in the United States; and WHEREAS, Juneteenth is also known as Emancipation Day, Emancipation Celebration, Freedom Day, and Jun-Jun; and WHEREAS, Juneteenth commemorates the strong survival instinct of African Americans who were first brought to this country stacked in the bottom of slave ships in a month-long journey across the Atlantic Ocean, known as the Middle Passage; and WHEREAS, approximately 11.5 million African Americans survived the voyage to the New World. The number that died is likely greater; and WHEREAS, events in the history of the United States which led to the Civil War centered around sectional differences between the North and the South that were based on the economic and social divergence caused by the existence of slavery; and WHEREAS, President Abraham Lincoln was inaugurated as President of the United States in 1861, and he believed and stated that the paramount objective of the Civil War was to save the Union rather than save or destroy slavery; and -1- LR351 LR351 WHEREAS, President Lincoln also stated his wish was that all men everywhere could be free, thus adding to a growing anticipation by slaves that their ultimate liberty was at hand; and WHEREAS, in 1862, the first clear signs that the end of slavery was imminent came when laws abolishing slavery in the territories -

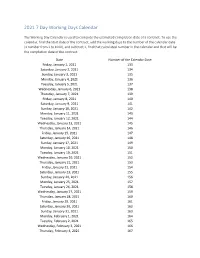

2021 7 Day Working Days Calendar

2021 7 Day Working Days Calendar The Working Day Calendar is used to compute the estimated completion date of a contract. To use the calendar, find the start date of the contract, add the working days to the number of the calendar date (a number from 1 to 1000), and subtract 1, find that calculated number in the calendar and that will be the completion date of the contract Date Number of the Calendar Date Friday, January 1, 2021 133 Saturday, January 2, 2021 134 Sunday, January 3, 2021 135 Monday, January 4, 2021 136 Tuesday, January 5, 2021 137 Wednesday, January 6, 2021 138 Thursday, January 7, 2021 139 Friday, January 8, 2021 140 Saturday, January 9, 2021 141 Sunday, January 10, 2021 142 Monday, January 11, 2021 143 Tuesday, January 12, 2021 144 Wednesday, January 13, 2021 145 Thursday, January 14, 2021 146 Friday, January 15, 2021 147 Saturday, January 16, 2021 148 Sunday, January 17, 2021 149 Monday, January 18, 2021 150 Tuesday, January 19, 2021 151 Wednesday, January 20, 2021 152 Thursday, January 21, 2021 153 Friday, January 22, 2021 154 Saturday, January 23, 2021 155 Sunday, January 24, 2021 156 Monday, January 25, 2021 157 Tuesday, January 26, 2021 158 Wednesday, January 27, 2021 159 Thursday, January 28, 2021 160 Friday, January 29, 2021 161 Saturday, January 30, 2021 162 Sunday, January 31, 2021 163 Monday, February 1, 2021 164 Tuesday, February 2, 2021 165 Wednesday, February 3, 2021 166 Thursday, February 4, 2021 167 Date Number of the Calendar Date Friday, February 5, 2021 168 Saturday, February 6, 2021 169 Sunday, February -

Juneteenth” Comes Ployer and Free Laborer

J UNETEENTH 92 C ELEBRATIONS UNETEENTH is the oldest celebration in the and the connection h eretofore existing be- nation to commemorate the end of slavery in tween them becomes that between em- J the United States. The word “Juneteenth” comes ployer and free laborer. from a colloquial pronunciation of “June 19th,” which With this announcement the last 250,000 slaves in is the date celebrations commemorate. the United States were effectively freed. Afterward In 1863 President Abraham Lincoln signed the many of the former slaves left Texas. As they moved to Emancipation Proclamation, offi - other states to fi nd family mem- cially freeing slaves. However, bers and start new lives, they car- word of the Proclamation did not ried news of the June 19th event reach many parts of the country with them. In subsequent decades right away, and instead the news former slaves and their descendants spread slowly from state to state. continued to commemorate June The slow spread of this important 19th and many even made pilgrim- news was i n part because the A mer- ages back to Galveston, Texas to ican Civil War had not yet ended. celebrate the event. However, in 1865 the Civil War Most of the celebrations ini- ended and Union Army soldiers tially took place in rural areas and began spreading the news of the included activities such as fi shing, war’s end and Lincoln’s Emanci- barbeques, and family reunions. pation Proclamation. Church grounds were also often On June 19, 1865, Major Gen- the sites for these celebrations. As eral Gordon Granger and U nion more and more African Americans Army soldiers arrived in Galves- improved their economic condi- ton, Texas. -

Juneteenth, the Commemoration of the End of Slavery in the United States, Is Celebrated by Black Americans Every June 19Th

To the LSU SVM Community, We recognize the pain and suffering of many of the black members of our SVM family. We are celebrating Juneteenth, and in light of the recent events, Stephanie Johnson has compiled a list of resources here for those in need (see below for a full list). We see you, we care and we are listening to your needs. Juneteenth, the commemoration of the end of slavery in the United States, is celebrated by Black Americans every June 19th. Read More About Juneteenth Juneteenth, the commemoration of the end of slavery in the United States, will be celebrated by Black Americans on Friday, June 19th amid a national reckoning on race prompted by the police killing of George Floyd and the sweeping demonstrations that followed. Here is information about the holiday, reprinted from the news article "What to know about Juneteenth, the emancipation holiday" by NBC News correspondent Daniella Silva. The article can be read in full here. On June 19, 1865, Gen. Gordon Granger arrived with Union soldiers in Galveston, Texas, and announced to enslaved Africans Americans that the Civil War had ended and they were free — more than two years after President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. At the time Lincoln issued the proclamation, there were minimal Union troops in Texas to enforce it, according to Juneteenth.com. But with the surrender of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee two months earlier and the arrival of Granger’s troops, the Union forces were now strong enough to enforce the proclamation. The holiday, which gets its name from the combination of June and Nineteenth, is also known as Emancipation Day, Juneteenth Independence Day and Black Independence Day. -

Ryan Covert, 586-907-0859, [email protected]

For Immediate Release Contact: Ryan Covert, 586-907-0859, [email protected] Jun 18, 2021 Detroit/Wayne County Port Authority Statement on Passage of the Juneteenth National Independence Day Act Detroit – The Detroit Wayne County Port Authority (DWCPA) released the following statement on behalf of Chairman Kinloch & the Board of Directors in response to yesterday’s signing of the Juneteenth National Independence Day Act.: 156 years ago tomorrow, with Union troops seizing control of Texas & the Civil War having ended, General Gordon Granger issued General Order #3 from his base in Galveston. The order telegraphed to all Texans that freedom was the law of the land and slavery would no longer be abided. From that day sprung an annual celebration among those freed to commemorate emancipation. Over the years it has been marked in different ways, reflecting the state & local nature of the holiday. However, yesterday President Biden signed into law the Juneteenth National Independence Day Act, finally bringing about federal recognition. Today the Port Authority joins in celebrating this day and the freedom for all that it signifies. In addition, we give thanks to all those who worked tirelessly to ensure the proper recognition of this holiday from localities, to states, and finally the federal government. As awareness of the holiday spreads, may it come to enjoy the universal reverence it deserves. “As an organization, we are honored to officially mark Juneteenth as a national day of reflection and celebration” said Chairman Jonathan C. Kinloch, “We are reminded that even as we celebrate, the work continues to build a more just, equal, and free society for all.” In observance of this day the Port Authority will close its administrative offices on Monday, June 21st.