S-1-SC-38228 STATE of NEW MEXICO, Ex Rel., M. KEITH RIDDLE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fact Sheet: Designation of Election Infrastructure As Critical Infrastructure

Fact Sheet: Designation of Election Infrastructure as Critical Infrastructure Consistent with Presidential Policy Directive (PPD) 21, the Secretary of Homeland Security has established Election Infrastructure as a critical infrastructure subsector within the Government Facilities Sector. Election infrastructure includes a diverse set of assets, systems, and networks critical to the administration of the election process. When we use the term “election infrastrucure,” we mean the key parts of the assets, systems, and networks most critical to the security and resilience of the election process, both physical locations and information and communication technology. Specficially, we mean at least the information, capabilities, physical assets, and technologies which enable the registration and validation of voters; the casting, transmission, tabulation, and reporting of votes; and the certification, auditing, and verification of elections. Components of election infrastructure include, but are not limited to: • Physical locations: o Storage facilities, which may be located on public or private property that may be used to store election and voting system infrastructure before Election Day. o Polling places (including early voting locations), which may be physically located on public or private property, and may face physical and cyber threats to their normal operations on Election Day. o Centralized vote tabulation locations, which are used by some states and localities to process absentee and Election Day voting materials. • Information -

NASS Resolution on Threats of Violence Toward Election Officials and Election Workers

NASS Resolution on Threats of Violence Toward Election Officials and Election Workers Introduced by Hon. Kyle Ardoin (R-LA) Co-Sponsored for Introduction by: Hon. Kevin Meyer (R-AK) Hon. John Merrill (R-AL) Hon. Jena Griswold (D-CO) Hon. Paul Pate (R-IA) Hon. Scott Schwab (R-KS) Hon. Michael Adams (R-KY) Hon. Jocelyn Benson (D-MI) Hon. Steve Simon (D-MN) Hon. Michael Watson (R-MS) Hon. Al Jaeger (R-ND) Hon. Maggie Toulouse Oliver (D-NM) Hon. Barbara Cegavske (R-NV) Hon. Shemia Fagan (D-OR) Hon. Kim Wyman (R-WA) WHEREAS, the 2020 election cycle was the most challenging in recent memory, with a global pandemic and multiple natural disasters affecting numerous states and their election infrastructure and processes; and WHEREAS, election workers across the country worked tirelessly under difficult conditions to ensure a fair, safe and accurate election for the more than 155 million voters in November; and WHEREAS, based upon unrelenting misinformation and disinformation from both domestic and foreign sources, extremists have taken to threatening and endangering election workers, from Secretaries of State, state election directors, local election officials and election workers; and WHEREAS, the cornerstone of our republic is the right of Americans to vote in a safe, secure and accurate election, and their exercising of that right; and WHEREAS, election workers are a vital part of ensuring the exercise of that right for all eligible Americans; and WHEREAS, violence and violent threats directed at Secretaries of State, their families, staff, and other election workers is abhorrent and the antithesis of what our nation stands for. -

Jena M. Griswold Colorado Secretary of State

Jena M. Griswold Colorado Secretary of State July 28, 2020 Senator Mitch McConnell Senator Charles E. Schumer Senator Richard C. Shelby Senator Patrick J. Leahy Senator Roy Blunt Senator Amy Klobuchar Dear Senators: As Secretaries of State of both major political parties who oversee the election systems of our respective states, we write in strong support of additional federal funding to enable the smooth and safe administration of elections in 2020. The stakes are high. And time is short. The COVID-19 pandemic is testing our democracy. A number of states have faced challenges during recent primary elections. Local administrators were sometimes overwhelmed by logistical problems such as huge volumes of last-minute absentee ballot applications, unexpected shortages of poll workers, and difficulty of procuring and distributing supplies. As we anticipate significantly higher voter turnout in the November General Election, we believe those kinds of problems could be even larger. The challenge we face is to ensure that voters and our election workers can safely participate in the election process. While none of us knows what the world will look like on November 3rd, the most responsible posture is to hope for the best and plan for the worst. The plans in each of our states depend on adequate resources. While we are truly grateful for the resources that Congress made available in the CARES Act for election administration, more funding is critical. Current funding levels help to offset, but do not cover, the unexpectedly high costs that state and local governments face in trying to administer safe and secure elections this year. -

Daily Congressional Record Corrections for 2019

Daily Congressional Record Corrections for 2019 VerDate Sep 11 2014 00:56 May 29, 2019 Jkt 089060 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 8392 Sfmt 8392 J:\CRONLINE\2019-BATCH-JAN\2019 TITLE PAGES FOR CRI INDEX\2019JANFEB.IDX 2 abonner on DSKBCJ7HB2PROD with CONG-REC-ONLINE VerDate Sep 11 2014 00:56 May 29, 2019 Jkt 089060 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 8392 Sfmt 8392 J:\CRONLINE\2019-BATCH-JAN\2019 TITLE PAGES FOR CRI INDEX\2019JANFEB.IDX 2 abonner on DSKBCJ7HB2PROD with CONG-REC-ONLINE Daily Congressional Record Corrections Note: Corrections to the Daily Congressional Record are identified online. (Corrections January 2, 2019 through February 28, 2019) Senate On page S8053, January 2, 2019, first column, The online Record has been corrected to read: the following appears: The PRESIDING OFFI- The PRESIDING OFFICER. Without objection, it CER. Without objection, it is so ordered. The is so ordered. The question is, Will the Senate ad- nominations considered and confirmed are as fol- vise and consent to the nominations of Robert S. lows: Robert S. Brewer, Jr., of California, to be Brewer, Jr., of California, to be United States At- United States Attorney for the Southern District of torney for the Southern District of California for California for the term of four years. Nicholas A. the term of four years; Nicholas A. Trutanich, of Trutanich, of Nevada, to be United States Attor- Nevada, to be United States Attorney for the Dis- ney for the District of Nevada for the term of four trict of Nevada for the term of four years; Brian years. -

See Our Full 2017-18 Impact Report

INTRODUCTION CONTENTS The 2018 cycle was a major step forward for the environment and our democracy, with impressive wins up and down the ballot. Your investment made an impact and allowed us 1 INTRODUCTION to gain a majority in the House of Representatives, maintain our green firewall in the Senate, elect 11 new governors, 2 OVERVIEW and help flip legislative chambers in 3 key states. 4 U.S. SENATE RESULTS The collective efforts of energized grassroots issues and are poised to make progress in activists, an amazing field of candidates, their states. And in Colorado, we helped flip and the unbelievably committed GiveGreen the State Senate, giving Colorado a pro- 6 U.S. HOUSE RESULTS donor community made these gains possible. environment trifecta that will promote clean The results speak for themselves. air, clean water, and a healthy future. 10 GOVERNORS RESULTS This year, with a new and improved website This cycle, more than 10,000 donors gave we were able to prioritize a slate of 242 House an astounding $23 million through GiveGreen, 12 STATE EXECUTIVES RESULTS and Senate candidates and 110 nonfederal our largest fundraising cycle to date. As we candidates across 41 states, in races where we look at the road ahead, we know that this assessed that contributions to these campaigns community will be more important than ever 14 STAGE LEGISLATORS RESULTS could help shift the balance of power. We to accelerate action on climate change. This helped win an incredible 74% of these races. report illustrates the impact of your giving. 16 WHY GIVEGREEN.COM By strategically contributing to candidates to- gether, we were able to harness the collective On behalf of NextGen America, LCV Victory power of environmental donors around the Fund, and NRDC Action Fund PAC, please know 17 CONTACT INFORMATION country — and maximize our impact. -

California Secretary of State Dr. Shirley N. Weber Statement on Signing Bipartisan Letter to CISA Secretary Mayorkas and Acting Director Wales

SW21:018 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE April 16, 2021 CONTACT: SOS Press Office (916) 653-6575 California Secretary of State Dr. Shirley N. Weber Statement on Signing Bipartisan Letter to CISA Secretary Mayorkas and Acting Director Wales SACRAMENTO, CA – California Secretary of State Dr. Shirley N. Weber issued the following statement on signing the letter to Department of Homeland Security’s Cyber and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) requesting an expansion of federal efforts to combat foreign disinformation. "Democracy exists because we have free and fair elections, and we must protect those elections at all costs. In 2020, our local and state election officials worked tirelessly to combat the spread of mis- and disinformation perpetuated by foreign actors seeking to diminish trust in our elections." "Without CISA's leadership combating this threat at the federal level, we would not be able to call the 2020 General Election the most secure in our nation's history. For this reason, I gladly join my bipartisan colleagues in calling on CISA not only to continue this vital work but expand its efforts to combat the ongoing threat of foreign interference in our elections." The complete letter can be accessed here and is co-signed by Kevin Meyer, Alaska Lt. Governor; Jena Griswold, Colorado Secretary of State; Shenna Bellows, Maine Secretary of State; William Francis Galvin, Secretary of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts; Jocelyn Benson, Michigan Secretary of State; Maggie Toulouse Oliver, New Mexico Secretary of State; Shemia Fagan, Oregon Secretary of State; Nellie Gorbea, Rhode Island Secretary of State; Jim Condos, Vermont Secretary of State, and Kim Wyman, Washington Secretary of State. -

Protecting Climate Progress by the Numbers

2015-2016 Elections Report: Protecting Climate Progress By the Numbers Total Investments in Elections over $45 Million Independent Expenditures $ $ $ 9.25Million 19Million 9.5Million Invested in the Presidential Race Invested in Congressional Races Invested in State Races with State LCVs Other Programs $ $ 8.4Million 1.5Million Invested in Candidates through Invested in LCV Membership GiveGreen and GiveGreen in the States Communications through GreenRoots Accomplishments of Independent Expenditure Investments 5.5Million 3,600 2.5Million Target Voters Contacted Staff in the Field Doors Knocked 11Million 20+ Pieces of Mail Sent TV and Digital Ads Aired Message from the President Dear Supporter, The outcome of this year’s elections were unexpected and very disappointing, especially at the federal level. Despite the difficult electoral outcomes, we are proud of our efforts this election cycle. This year we spent more than ever before—over $45 million—and we came away with an array of important successes, particularly at the state level. In North Carolina, Washington and Montana—all of LCV’s priority governor’s races—pro-environment candidates were elected. Furthermore, we helped our state partners win pro-clean energy majorities in several state legislatures, including Nevada, New Mexico and Maine. And, in Florida, we supported our state ally’s effort to decisively defeat an industry-led anti-solar ballot measure, despite being outspent by tens of millions of dollars. These are not small wins. With momentum in the states, strong public preference for government involvement in combatting climate change, and the transition towards clean energy underway, we are still poised to make progress on our climate goals. -

August 7, 2020 the Honorable Louis Dejoy United States Postmaster General 475 L'enfant Plaza SW Washington, D.C. 20260 Dear Po

NASS EXECUTIVE August 7, 2020 BOARD The Honorable Louis DeJoy Hon. Maggie Toulouse Oliver, NM United States Postmaster General President 475 L’Enfant Plaza SW Washington, D.C. 20260 Hon. R. Kyle Ardoin, LA President-elect Dear Postmaster General DeJoy: Hon. Tahesha Way, NJ Treasurer As the President, President-elect and Elections Committee Co-Chairs of Hon. Steve Simon, MN Secretary the National Association of Secretaries of State (NASS), we come together to invite you to participate in a call or virtual meeting with the four of us Hon. Paul Pate, IA Immediate Past President the week of August 10, 2020, to discuss United States Postal Service (USPS) mail service for the November general election. Hon. Nellie Gorbea, RI Eastern Region Vice President NASS is the oldest nonpartisan professional organization for elected officials and 40 of our members serve as their state’s chief election official. Hon. John Merrill, AL Southern Region Vice President State and local election officials are busy planning for the November Hon. Scott Schwab, KS general election and many expect an increase in the use of absentee and Midwestern Region Vice mail ballots, along with other election-related mailings. We view the USPS President as a vital partner in administering a safe, successful election and would like Hon. Katie Hobbs, AZ to learn more about any planned changes around USPS service due to Western Region Vice COVID-19, preparations for increased election-related mail, USPS staffing President levels and processing times, and other pertinent issues. Hon. Jim Condos, VT Member-at-Large (ACR) We look forward to having a call with you. -

June 28, 2021 the Honorable Nancy Pelosi the Honorable Chuck

June 28, 2021 The Honorable Nancy Pelosi The Honorable Chuck Schumer Speaker Majority Leader United States House of Representatives United States Senate 1236 Longworth House Office Building 322 Hart Senate Office Building Washington, DC 20515 Washington, DC 20510 The Honorable Kevin McCarthy The Honorable Mitch McConnell Minority Leader Minority Leader United States House of Representatives United States Senate 2468 Rayburn House Office Building 317 Russell Senate Office Building Washington, DC 20515 Washington, DC 20510 Re: Inclusion of funding for Election Infrastructure in Infrastructure package Dear Speaker Pelosi, Leader Schumer, Leader McCarthy, and Leader McConnell: We write to you as bipartisan Secretaries of State from across the United States, to urge you to include critical funding for election infrastructure in the infrastructure package Congress is considering this year. As Chief Election Officials of our respective states, we are entrusted with conducting, funding, and supporting local, state, and federal elections in jurisdictions across the country. Election security and integrity are a vital cornerstone of our democracy, and we strongly urge you to support this critical and necessary investment. In 2017, the Department of Homeland Security designated election infrastructure, including the systems, equipment, and facilities needed to administer our country’s elections, as a vital part of the federal government’s Critical Infrastructure. Like other sectors of critical infrastructure, we need to ensure that we can continue to build and strengthen our systems and equipment for the protection of our democracy: to ensure the ability of all eligible voters to exercise their fundamental right to vote in safe, secure, and accessible elections. Our success is dependent on substantial and sustained dedication of resources, and a federal commitment to longer-term investment must start now. -

Secretary of State DENNIS RICHARDSON

From: Dodd, Stacy To: Dodd, Stacy; Dodd, Stacy Cc: Reynolds, Leslie; Milhofer, John; Maria Benson Subject: Call for Nominations: NASS 2018 Margaret Chase Smith American Democracy Award Date: Monday, March 12, 2018 6:07:02 AM Attachments: mcs-award-nominating-form-2018.doc mcs-call-for-nominations-2018.pdf Dear NASS Members: Do you know someone whose politically-courageous decision-making is worthy of national recognition? NASS is currently seeking nominations for the 2018 Margaret Chase Smith American Democracy Award, which seeks to recognize uncommon acts of political courage and exceptional character for the common good. Attached are background and nominating forms to guide your submission. Nominations must be submitted by no later than 5:00 PM EDT on THURSDAY, May 3, 2018. Please note, the eligibility guidelines for this award include the following: · Any individual, other than Secretaries of State or Lieutenant Governors currently holding office, may be nominated for this award. · NASS encourages emphasis on more contemporary acts of political courage, although all legitimate nominations will be considered. The goal is to recognize a person (or persons, if merit exists) for documented contributions to civic/political life in the U.S. · Ideally, emphasis should be placed on living Americans who are not currently holding elected or appointed office. However, exceptions may be considered in deserving cases. As the association’s most prestigious award, we encourage you to make it a priority to nominate a worthy recipient for the Margaret Chase Smith Award. A list of past recipients is available online. Nominations that were not selected for consideration in the past may be re-submitted for this year. -

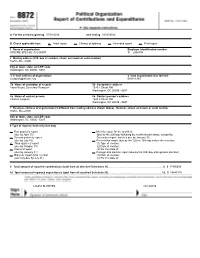

A for the Period Beginning 07/01/2014 and Ending 09/30/2014

A For the period beginning 07/01/2014 and ending 09/30/2014 B Check applicable box: ✔ Initial report Change of address Amended report Final report 1 Name of organization Employer identification number AFSCME SPECIAL ACCOUNT 91 - 2064198 2 Mailing address (P.O. box or number, street, and room or suite number) 1625 L Street NW City or town, state, and ZIP code Washington, DC 20036 - 5687 3 E-mail address of organization: 4 Date organization was formed: [email protected] 08/01/1980 5a Name of custodian of records 5b Custodian's address Laura Reyes, Secretary-Treasurer 1625 L Street NW Washington, DC 20036 - 5687 6a Name of contact person 6b Contact person's address Charles Jurgonis 1625 L Street NW Washington, DC 20036 - 5687 7 Business address of organization (if different from mailing address shown above). Number, street, and room or suite number 1625 L Street NW City or town, state, and ZIP code Washington, DC 20036 - 5687 8 Type of report (check only one box) First quarterly report Monthly report for the month of: (due by April 15) (due by the 20th day following the month shown above, except the Second quarterly report December report, which is due by January 31) (due by July 15) Pre-election report (due by the 12th or 15th day before the election) ✔ Third quarterly report (1) Type of election: (due by October 15) (2) Date of election: Year-end report (3) For the state of: (due by January 31) Post-general election report (due by the 30th day after general election) Mid-year report (Non-election (1) Date of election: year only-due by July 31) (2) For the state of: 9 Total amount of reported contributions (total from all attached Schedules A) .......................................................................... -

TABLE 4.15 the Secretaries of State, 2018

SECRETARIES OF STATE TABLE 4.15 The Secretaries of State, 2018 Maximum consecutive State or other Method of Length of regular Date of first Present term Number of terms allowed by jurisdiction Name and party Selection term in years service ends previous terms constitution Alabama John Merrill (R) E 4 1/2015 1/2019 … 2 Alaska --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- (a) --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Arizona Michele Reagan (R) E 4 1/2015 1/2019 … 2 Arkansas Mark Martin (R) E 4 1/2011 1/2019 1 2 California Alex Padilla (D) E 4 1/2015 1/2019 … 2 Colorado Wayne Williams (R) E 4 1/2015 1/2019 … 2 Connecticut Denise Merrill (D) E 4 1/2011 1/2019 1 … Delaware Jeffrey Bullock (D) A (b) 4 1/2009 … … … Florida Kenneth Detzner (R) A 4 2/2012 … 1 2 Georgia Brian Kemp (R) E 4 1/2010 1/2019 1 … Hawaii --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- (a) --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Idaho Lawerence Denney (R) E 4 1/2015 1/2019 … … Illinois Jesse White (D) E 4 1/1999 1/2019 4 … Indiana Connie Lawson (R) E 4 3/2012 1/2019 1 2 Iowa Paul Pate (R) E 4 12/2014 12/2018 … … Kansas Kris Kobach (R) E 4 1/2011 1/2019 1 … Kentucky Alison Lundergan Grimes (D) E 4 12/2011 12/2019 1 2 Louisiana Kyle Ardoin (R) (acting) E 4 5/2018 (c) 1/2020 … … Maine Matt Dunlap (D) L 2 1/2005 (d) 1/2019 (d) 5 (e) Maryland John Wobensmith (R) A … 1/2015 … … … Massachusetts William Francis Galvin (D) E 4 1/1995 1/2019 5 … Michigan Ruth Johnson (R) E 4 1/2011 1/2019 1 2 Minnesota Steve Simon (DFL) E 4 1/2015 1/2019 … … Mississippi C.