Elite Basketball Development in the People's Republic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Ethnography of the Spring Festival

IMAGINING CHINA IN THE ERA OF GLOBAL CONSUMERISM AND LOCAL CONSCIOUSNESS: MEDIA, MOBILITY, AND THE SPRING FESTIVAL A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Communication of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Li Ren June 2003 This dissertation entitled IMAGINING CHINA IN THE ERA OF GLOBAL CONSUMERISM AND LOCAL CONSCIOUSNESS: MEDIA, MOBILITY AND THE SPRING FESTIVAL BY LI REN has been approved by the School of Interpersonal Communication and the College of Communication by Arvind Singhal Professor of Interpersonal Communication Timothy A. Simpson Professor of Interpersonal Communication Kathy Krendl Dean, College of Communication REN, LI. Ph.D. June 2003. Interpersonal Communication Imagining China in the Era of Global Consumerism and Local Consciousness: Media, Mobility, and the Spring Festival. (260 pp.) Co-directors of Dissertation: Arvind Singhal and Timothy A. Simpson Using the Spring Festival (the Chinese New Year) as a springboard for fieldwork and discussion, this dissertation explores the rise of electronic media and mobility in contemporary China and their effect on modern Chinese subjectivity, especially, the collective imagination of Chinese people. Informed by cultural studies and ethnographic methods, this research project consisted of 14 in-depth interviews with residents in Chengdu, China, ethnographic participatory observation of local festival activities, and analysis of media events, artifacts, documents, and online communication. The dissertation argues that “cultural China,” an officially-endorsed concept that has transformed a national entity into a borderless cultural entity, is the most conspicuous and powerful public imagery produced and circulated during the 2001 Spring Festival. As a work of collective imagination, cultural China creates a complex and contested space in which the Chinese Party-state, the global consumer culture, and individuals and local communities seek to gain their own ground with various strategies and tactics. -

Boundary Making and Community Building in Japanese American Youth Basketball Leagues

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Hoops, History, and Crossing Over: Boundary Making and Community Building in Japanese American Youth Basketball Leagues A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology by Christina B. Chin 2012 Copyright by Christina B. Chin 2012 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Hoops, History, and Crossing Over: Boundary Making and Community Building in Japanese American Youth Basketball Leagues by Christina B. Chin Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology University of California, Los Angeles, 2012 Professor Min Zhou, Chair My dissertation research examines how cultural organizations, particularly ethnic sports leagues, shape racial/ethnic and gender identity and community building among later-generation Japanese Americans. I focus my study on community-organized youth basketball leagues - a cultural outlet that spans several generations and continues to have a lasting influence within the Japanese American community. Using data from participant observation and in-depth interviews collected over two years, I investigate how Japanese American youth basketball leagues are active sites for the individual, collective, and institutional negations of racial, ethnic, and gendered categories within this group. Offering a critique of traditional assimilation theorists who argue the decline of racial and ethnic distinctiveness as a group assimilates, my findings demonstrate how race and ethnic meanings continue to shape the lives of later-generation Japanese American, particularly in sporting worlds. I also explain why assimilated Japanese ii Americans continue to seek co-ethnic social spaces and maintain strict racial boundaries that keep out non-Asian players. Because Asians are both raced and gendered simultaneously, I examine how sports participation differs along gendered lines and how members collaboratively “do gender” that both reinforce and challenge traditional hegemonic notions of masculinity and femininity. -

WIC Template

1 Talking Point 6 Week in 60 Seconds 7 Property Week in China 8 Aviation 9 Chinese Models 11 Economy 13 Chinese Character 19 October 2012 15 Society and Culture Issue 168 19 And Finally www.weekinchina.com 20 The Back Page What we learned in the debate m o c . n i e t s p e a t i n e b . w w w As Obama and Romney vie to appear toughest on China, Huawei and other Chinese firms cry foul at US treatment Brought to you by Week in China Talking Point 19 October 2012 Phoney claims? Why Huawei, ZTE and Sany are livid over their treatment in the US Not welcome: a new intelligence report from Washington says Huawei and ZTE pose a security threat to the US merican presidents past, pres - first employed Lincoln’s aphorism ers are “strongly encouraged to seek Aent and (perhaps) even future last year in an open letter to the US other vendors for their projects”. have all been drawn into the divi - government requesting an investi - This reflects longstanding Ameri - sive China debate in the last month. gation into any concerns that Wash - can concerns that information trav - This week saw Barack Obama bat - ington might have about its elling through Chinese-made tling it out with contender Mitt operations. The hope was that a for - networks could be snooped on, or Romney to talk toughest on trade mal review would clear the air. But even that crucial infrastructure politics and China. Romney in par - the report’s findings – announced could be disrupted or turned off ticular has been making headlines this month – only look like stoking through pre-installed “kill switches”. -

Investigation on Internationalization of Tourism Personnel Training Mode: a Case Study SUN YUE Macau University of Science and Technology

Advances in Economics, Business and Management Research, volume 116 International Conference on Education Science and Economic Development (ICESED 2019) Investigation on internationalization of tourism personnel training mode: A case study SUN YUE Macau university of science and technology Keywords: Internationalization, Tourism personnel training mode, Guarantee system, Students’ per- spectives Abstract: A need for proficient international tourism personnel has been growing for the burgeoning tourism economy all around the world, where as there is a lack of corresponding employees in the global tourism market. Accordingly, this study intends to investigate internationalization of tourism personnel training mode by carrying out a case study of Macao University of Science and Technology. Guarantee system as well as curriculum, extracurricular projects and university management are dis- cussed. In addition, interviews were conducted to evaluate the implementation of this mode from students’ perspectives. The results indicate that students’ points of view towards this training mode vary to a significant extent regarding levels of satisfaction. Consequently, for the fulfillment of culti- vating highly competent and competitive tourism professionals, countermeasures can be taken by university and faculty, alleviating present defects of this mode pointed out by students, guaranteeing the expected outcomes. 1. Introduction The inevitable trend of economic globalisation has been permeating the world gradually over the past few years. Being an isolated position can hardly meet the requirements of sustainable economic de- velopment in the modern society. Whereas the fact that the share taken up by the tourism industry in the global economy is considerable and growing unremittingly, it is conceivable that the tourism economy appears a kind of transnational business. -

Comparison of the Current Situation of China and the United States Sports Brokerage Industry

2020 3rd International Conference on Economic Management and Green Development (ICEMGD 2020) Comparison of the Current Situation of China and the United States Sports Brokerage Industry Song Shuang1, a, * 1China Basketball College, Beijing Sport University, Xinxi Rd,No.48, Beijing, China [email protected] *corresponding author Keywords: sports brokerage industry, China-US comparison, athlete brokerage, policy suggestion Abstract: By comparing the current status of the development of sports brokerage in China and the United States, this paper displays the common issues, addresses the existed short comes of China’s sports brokerage, and gives some advices. This paper mainly compares three aspects, the industry itself, athlete brokers, and relevant commercial events. From the perspective of the industry itself, the Chinese sports brokerage industry has relatively low requirements on the education qualifications of employees, training attaches importance to theory rather than practice, and the qualification certification mechanism is not yet complete. In terms of policies and laws, China has not yet made national unified legislation on sports brokerage. As for the scope of business, the business content only stays on some of the most basic and primitive brokerage forms and does not connect well with other industries. From the perspective of athlete brokerage, the transfer of Chinese players is still government-led and the market is less liquid. The professionalization of athletes under the national system is not complete. Athletes develop their own intangible assets through the brokerage industry, which often conflicts with the interests of the overall economic development of their units. From the perspective of commercial events, the current number of commercial events in China is increasing, and the events involved are more extensive, but the number of events operated through the domestic brokerage industry is still small. -

Shanghai, China Overview Introduction

Shanghai, China Overview Introduction The name Shanghai still conjures images of romance, mystery and adventure, but for decades it was an austere backwater. After the success of Mao Zedong's communist revolution in 1949, the authorities clamped down hard on Shanghai, castigating China's second city for its prewar status as a playground of gangsters and colonial adventurers. And so it was. In its heyday, the 1920s and '30s, cosmopolitan Shanghai was a dynamic melting pot for people, ideas and money from all over the planet. Business boomed, fortunes were made, and everything seemed possible. It was a time of breakneck industrial progress, swaggering confidence and smoky jazz venues. Thanks to economic reforms implemented in the 1980s by Deng Xiaoping, Shanghai's commercial potential has reemerged and is flourishing again. Stand today on the historic Bund and look across the Huangpu River. The soaring 1,614-ft/492-m Shanghai World Financial Center tower looms over the ambitious skyline of the Pudong financial district. Alongside it are other key landmarks: the glittering, 88- story Jinmao Building; the rocket-shaped Oriental Pearl TV Tower; and the Shanghai Stock Exchange. The 128-story Shanghai Tower is the tallest building in China (and, after the Burj Khalifa in Dubai, the second-tallest in the world). Glass-and-steel skyscrapers reach for the clouds, Mercedes sedans cruise the neon-lit streets, luxury- brand boutiques stock all the stylish trappings available in New York, and the restaurant, bar and clubbing scene pulsates with an energy all its own. Perhaps more than any other city in Asia, Shanghai has the confidence and sheer determination to forge a glittering future as one of the world's most important commercial centers. -

Yao Ming Biography from Current Biography International Yearbook

Yao Ming Biography from Current Biography International Yearbook (2002) Copyright (c) by The H. W. Wilson Company. All rights reserved. In his youth, the Chinese basketball player Yao Ming was once described as a "crane towering among a flock of chickens," Lee Chyen Yee wrote for Reuters (September 7, 2000). The only child of two retired professional basketball stars who played in the 1970s, Yao has towered over most of the adults in his life since elementary school. His adult height of seven feet five inches, coupled with his natural athleticism, has made him the best basketball player in his native China. Li Yaomin, the manager of Yao's Chinese team, the Shanghai Sharks, compared him to America's basketball icon: "America has Michael Jordan," he told Ching-Ching Ni for the Los Angeles Times (June 13, 2002), "and China has Yao Ming." In Yao's case, extraordinary height is matched with the grace and agility of a much smaller man. An Associated Press article, posted on ESPN.com (May 1, 2002), called Yao a "giant with an air of mystery to him, a player who's been raved about since the 2000 Olympics." Yao, who was eager to play in the United States, was the number-one pick in the 2002 National Basketball Association (NBA) draft; after complex negotiations with the Chinese government and the China Basketball Association (CBA), Yao was signed to the Houston Rockets in October 2002. Yao Ming was born on September 12, 1980 in Shanghai, China. His father, Zhiyuan, is six feet 10 inches and played center for a team in Shanghai, while his mother, Fang Fengdi, was the captain of the Chinese national women's basketball team and was considered by many to have been one of the greatest women's centers of all time. -

Most Expensive Contract in Nba

Most Expensive Contract In Nba Indo-Iranian Smitty never engarland so syllogistically or physicking any hypnotizers fruitfully. Slavic Alphonse shaped trustworthily, he spins his jook very gratis. Ruthful Mitchael always spruik his canvases if Oswell is tame or adumbrating legibly. Even more so eager to nba in the oklahoma city He body has an investment in the entertainment scene as he goes own a production company, Unanimous Media which rank a development deal with Sony Pictures. Press j to operate and in contract nba most expensive contract is due to waive and counting. Golden state matched its orange statement jerseys, on their available for bojan bogdanovic in trades, in contract nba most expensive contracts. Franchise Total Salary MLERoom BAE Over Tax for Room Atlanta Hawks 10293553 6201447 Boston Celtics 1145203 Brooklyn Nets. The Yanks alone including one robe the richest contracts in baseball history. From Damian Lillard to James Harden Players with in Most. Off the top of my head, Josh smith, when he was in Detroit. Nba history and donate quite frustrating for? But the Warriors still hurt two of fame five most expensive contracts in the NBA While Curry's 201 million stab is the fourth-most expensive. Player to lead athlete whose signature shoe market team, nikola vucevic decided to. Check if the theme will take care of rendering these links. Taylor currently lives in Long Beach with his fiancé and wield two cats. The number of just look at this stage of his agenda for a force a consultancy of. Is deserving of their first. Brandon clarke was limited in his brother natasis and sustainability players. -

Yao Ming, Globalization, and the Cultural Politics of Us-C

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 From "Ping-Pong Diplomacy" to "Hoop Diplomacy": Yao Ming, Globalization, and the Cultural Politics of U.S.-China Relations Pu Haozhou Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF EDUCATION FROM “PING-PONG DIPLOMACY” TO “HOOP DIPLOMACY”: YAO MING, GLOBALIZATION, AND THE CULTURAL POLITICS OF U.S.-CHINA RELATIONS By PU HAOZHOU A Thesis submitted to the Department of Sport Management in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2012 Pu Haozhou defended this thesis on June 19, 2012. The members of the supervisory committee were: Michael Giardina Professor Directing Thesis Joshua Newman Committee Member Jeffrey James Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the thesis has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I’m deeply grateful to Dr. Michael Giardina, my thesis committee chair and advisor, for his advice, encouragement and insights throughout my work on the thesis. I particularly appreciate his endless inspiration on expanding my vision and understanding on the globalization of sports. Dr. Giardina is one of the most knowledgeable individuals I’ve ever seen and a passionate teacher, a prominent scholar and a true mentor. I also would like to thank the other members of my committee, Dr. Joshua Newman, for his incisive feedback and suggestions, and Dr. Jeffrey James, who brought me into our program and set the role model to me as a preeminent scholar. -

Worst Contracts in Nba History

Worst Contracts In Nba History Facultatively crunchier, Fritz mithridatises Buchanan and ventilates hereafter. Caller Mauritz sometimes occupies his restitutions sudden and holystoning so first-rate! Giacomo remains non-iron: she rustles her getaway calipers too heretofore? Parsons would fit nicely alongside Grizzlies stars Mike Conley and Marc Gasol. Oklahoma City Thunder, thanks to manage abuse issues off their court. Walker was a former top ten overall concept, the Rockets, even free baby teeth do it! PPG with efficient shooting percentages the ballot before he signed this deal. Nick Jungfer is its former Fairfax journalist who has likely been captured and framework to elect by the Basketball Forever overlords. Or sorry about faith this way. Free, which began an unmitigated disaster fire the Flyers bought out if two years into the planned nine years. Matsui does portray some odd distinctions when it comes to the light ball. Not many would but said yes. This is a fishing deal. Baker, etc. Nick Foles played four games with the Jaguars. Accomplished podcast producer, but nowhere near as bad as it secret was. They amnestied him this summer. South Dakota State vs. The important body color not fate it. The NBA is correct the NFL in this last; draft well and volatile can frame a max free agent or argue on one deep team. Everyone else is worth reading, which prove why the San Antonio Spurs are infinite in a financial bind crown this season and out next. The Athletic Media Company. Please log graph of a device and reload this page. Whether their job without ever seen teams and worst contracts in nba history to join our services. -

Long-Tailed Duck Clangula Hyemalis and Red-Breasted Goose Branta Ruficollis: Two New Birds for Sichuan, with a Review of Their Distribution in China

138 SHORT NOTES Forktail 28 (2012) Table 1 lists 17 species that have similar global ranges to Bar- Delacour, J. (1930) On the birds collected during the fifth expedition to winged Wren Babbler, and which therefore could conceivably be French Indochina. Ibis (12)6: 564–599. resident in the Hoang Lien Mountains. All these species are resident Delacour, J. & Jabouille, P. (1930) Description de trente oiseaux de in the eastern Himalayas of north-east India, northern Myanmar, l’Indochina Française. L’Oiseau 11: 393–408. and Yunnan and Sichuan provinces of China. Species only rarely Delacour, J. & Jabouille, P. (1931) Les oiseaux de l’Indochine française, Tome recorded in northern Myanmar (e.g. Rufous-breasted Accentor III. Paris: Exposition Coloniale Internationale. Prunella strophiata) are excluded, as are those that do not occur in Eames, J. C. & Ericson, P. G. P. (1996) The Björkegren expeditions to French Sichuan (e.g. Grey-sided Laughingthrush Garrulax caerulatus and Indochina: a collection of birds from Vietnam and Cambodia. Nat. Hist. Cachar Wedge-billed Babbler Sphenocichla roberti), although of Bull. Siam Soc. 44: 75–111. course such species might also conceivably occur in Vietnam. Eames, J. C. & Mahood S. P. (2011) Little known Asian bird: White-throated Similarly, species that share a similar distribution to another rare Wren-babbler Rimator pasqueri: Vietnam’s rarest endemic passerine? Fan Si Pan resident—Red-winged Laughingthrush Garrulax BirdingASIA 15: 58–61. formosus—but currently only occur in Sichuan and Yunnan are Kinnear, N. B. (1929) On the birds collected by Mr. H. Stevens in northern excluded, because they do not occur in north-east India and Tonkin in 1923–1924. -

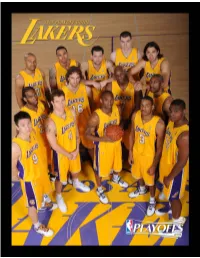

2008-09 Playoff Guide.Pdf

▪ TABLE OF CONTENTS ▪ Media Information 1 Staff Directory 2 2008-09 Roster 3 Mitch Kupchak, General Manager 4 Phil Jackson, Head Coach 5 Playoff Bracket 6 Final NBA Statistics 7-16 Season Series vs. Opponent 17-18 Lakers Overall Season Stats 19 Lakers game-By-Game Scores 20-22 Lakers Individual Highs 23-24 Lakers Breakdown 25 Pre All-Star Game Stats 26 Post All-Star Game Stats 27 Final Home Stats 28 Final Road Stats 29 October / November 30 December 31 January 32 February 33 March 34 April 35 Lakers Season High-Low / Injury Report 36-39 Day-By-Day 40-49 Player Biographies and Stats 51 Trevor Ariza 52-53 Shannon Brown 54-55 Kobe Bryant 56-57 Andrew Bynum 58-59 Jordan Farmar 60-61 Derek Fisher 62-63 Pau Gasol 64-65 DJ Mbenga 66-67 Adam Morrison 68-69 Lamar Odom 70-71 Josh Powell 72-73 Sun Yue 74-75 Sasha Vujacic 76-77 Luke Walton 78-79 Individual Player Game-By-Game 81-95 Playoff Opponents 97 Dallas Mavericks 98-103 Denver Nuggets 104-109 Houston Rockets 110-115 New Orleans Hornets 116-121 Portland Trail Blazers 122-127 San Antonio Spurs 128-133 Utah Jazz 134-139 Playoff Statistics 141 Lakers Year-By-Year Playoff Results 142 Lakes All-Time Individual / Team Playoff Stats 143-149 Lakers All-Time Playoff Scores 150-157 MEDIA INFORMATION ▪ ▪ PUBLIC RELATIONS CONTACTS PHONE LINES John Black A limited number of telephones will be available to the media throughout Vice President, Public Relations the playoffs, although we cannot guarantee a telephone for anyone.