Ashevillesurveyupdate Phase Iisummary Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

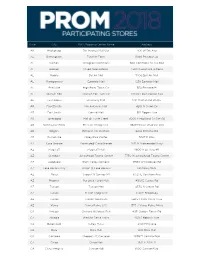

Prom 2018 Event Store List 1.17.18

State City Mall/Shopping Center Name Address AK Anchorage 5th Avenue Mall-Sur 406 W 5th Ave AL Birmingham Tutwiler Farm 5060 Pinnacle Sq AL Dothan Wiregrass Commons 900 Commons Dr Ste 900 AL Hoover Riverchase Galleria 2300 Riverchase Galleria AL Mobile Bel Air Mall 3400 Bell Air Mall AL Montgomery Eastdale Mall 1236 Eastdale Mall AL Prattville High Point Town Ctr 550 Pinnacle Pl AL Spanish Fort Spanish Fort Twn Ctr 22500 Town Center Ave AL Tuscaloosa University Mall 1701 Macfarland Blvd E AR Fayetteville Nw Arkansas Mall 4201 N Shiloh Dr AR Fort Smith Central Mall 5111 Rogers Ave AR Jonesboro Mall @ Turtle Creek 3000 E Highland Dr Ste 516 AR North Little Rock Mc Cain Shopg Cntr 3929 Mccain Blvd Ste 500 AR Rogers Pinnacle Hlls Promde 2202 Bellview Rd AR Russellville Valley Park Center 3057 E Main AZ Casa Grande Promnde@ Casa Grande 1041 N Promenade Pkwy AZ Flagstaff Flagstaff Mall 4600 N Us Hwy 89 AZ Glendale Arrowhead Towne Center 7750 W Arrowhead Towne Center AZ Goodyear Palm Valley Cornerst 13333 W Mcdowell Rd AZ Lake Havasu City Shops @ Lake Havasu 5651 Hwy 95 N AZ Mesa Superst'N Springs Ml 6525 E Southern Ave AZ Phoenix Paradise Valley Mall 4510 E Cactus Rd AZ Tucson Tucson Mall 4530 N Oracle Rd AZ Tucson El Con Shpg Cntr 3501 E Broadway AZ Tucson Tucson Spectrum 5265 S Calle Santa Cruz AZ Yuma Yuma Palms S/C 1375 S Yuma Palms Pkwy CA Antioch Orchard @Slatten Rch 4951 Slatten Ranch Rd CA Arcadia Westfld Santa Anita 400 S Baldwin Ave CA Bakersfield Valley Plaza 2501 Ming Ave CA Brea Brea Mall 400 Brea Mall CA Carlsbad Shoppes At Carlsbad -

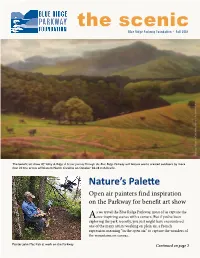

2018 Fall Issue of the Scenic

the scenic Blue Ridge Parkway Foundation - Fall 2018 Painting “Moses H. Cone Memorial Park” by John Mac Kah John Cone Memorial Park” by “Moses H. Painting The benefit art show Of Valley & Ridge: A Scenic Journey Through the Blue Ridge Parkway will feature works created outdoors by more than 20 fine artists of Western North Carolina on October 26-28 in Asheville. Nature’s Palette Open air painters find inspiration on the Parkway for benefit art show s we travel the Blue Ridge Parkway, most of us capture the Aawe-inspiring scenes with a camera. But if you’ve been exploring the park recently, you just might have encountered one of the many artists working en plein air, a French expression meaning “in the open air,” to capture the wonders of the mountains on canvas. Painter John Mac Kah at work on the Parkway Continued on page 2 Continued from page 1 Sitting in front of small easels with brushes and paint-smeared palettes in hand, these artists leave the walls of the studio behind to experience painting amid the landscape and fresh air. The Saints of Paint and Blue Ridge Parkway Foundation are inviting guests on a visual adventure with the benefit art show, Of Valley & Ridge: A Scenic Journey Through the Blue Ridge Parkway, showcasing the works of Western North Carolina fine artists from October 26 to 28 at Zealandia castle in Asheville, North Carolina. The show opens with a ticketed gala from 5 to 8 p.m., Friday, October 26, at the historical Tudor mansion, Zealandia, atop Beaucatcher Mountain. -

BLUE RIDGE BIKE PLAN for BUNCOMBE, Haywood, Henderson, Jackson, Madison, Swain, Transylvania Counties - North Carolina Acknowledgments

2013 BLUE RIDGE BIKE PLAN FOR BUNCOMBE, HAYWOOD, HENDERSON, JACKSON, MADISON, SWAIN, TRANSYLVANIA COUNTIES - NORTH CAROLINA ACKNOWLEDGMENTS SPECIAL THANKS Thank you to the more than 600 residents, bicycle shops and clubs, business owners and government employees who participated in meetings, surveys, and regional workgroups. We appreciate all your time and dedication to the development of this plan. STEERING COMMITTEE PROJECT TEAM Susan Anderson, City of Hendersonville Erica Anderson, AICP, Land of Sky Regional Council Paul Benson, Town of Waynesville Jon Beck, Land of Sky Regional Council Lynn Bowles, Madison County John Connell, Land of Sky Regional Council Matt Cable, Henderson County Vicki Eastland, French Broad River MPO Mike Calloway, NC Department of Transportation, Division 13 Christina Giles, Land of Sky Regional Council Claire Carleton, Haywood County Linda Giltz, AICP, Land of Sky Regional Council Kristy Carter, NC Department of Commerce/Appalachian Regional Commission Sarah Graham, Southwestern Commission Nathan Clark, Haywood County Josh King, AICP, Land of Sky RPO Daniel Cobb, City of Brevard Don Kostelec, AICP, Kostelec Planning, LLC Chris Cooper, Jackson County Philip Moore, Southwestern RPO Lucy Crown, Buncombe County Natalie Murdock, Land of Sky RPO Jill Edwards, Town of Black Mountain John Vine-Hodge, NC DOT, Division of Bicycle and Carolyn Fryberger, Town of Black Mountain Pedestrian Transportation Gerald Green, Jackson County Lyuba Zuyeva, French Broad River MPO Jessica Hocz, Madison County Preston Jacobsen, Haywood -

Asheville and Buncombe County

.1 (? Collection of American ILiteratur^ Ikqucatfjeb to Cfje ilibrarp of ttje Hnibersitp of i^ortf) Carolina "He gave back as rain that which he ^>^ receiveei as mist" D97/. !/-S7,9 00032761146 FOR USE ONLY IN THE NORTH CAROLINA COLLECTION w^ r I . \ STATEMENT November of last year The Asheville Citizen moved into its new INand permanent home at No. 25 Haywood Street. In celebration of that event The Citizen published a special edition, in which appeared two most interesting and highly instructive articles on the history of Western North Carolina and of Buncombe County, one prepared by Dr. F. A. Sondley, and the other by General Theodore F. Davidson, These two articles attracted widespread attention as they both narrated incidents and facts, many of which had never before been printed, and many of The Citizen's readers urged tliat these two articles be reprinted in pamphlet form, so as to be more easily read and pre- served for the future. At our request Dr. Sondley and General Davidson have both revised those two articles and have brought them up to date, and, in response to this request. The Citizen has had them printed and bound in this little volume. The Citizen believes that the public will be deeply interested in the facts set forth in this little volume, and is glad to have the oppor- tunity^ of performing what it believes is a great public service in hand- ing them down for future generations. The expense of securing the illustrations and the printing of this volume is considerably more than the . -

Store # State City Mall/Shopping Center Name Address Date 2918

Store # State City Mall/Shopping Center Name Address Date 2918 AL ALABASTER COLONIAL PROMENADE 340 S COLONIAL DR Coming Soon in September 2016! 2218 AL HOOVER RIVERCHASE GALLERIA 2300 RIVERCHASE GALLERIA Coming Soon in September 2016! 2131 AL HUNTSVILLE MADISON SQUARE 5901 UNIVERSITY DR Coming Soon in September 2016! 219 AL MOBILE BEL AIR MALL MOBILE, AL 36606-3411 Coming Soon in September 2016! 2840 AL MONTGOMERY EASTDALE MALL MONTGOMERY, AL 36117-2154 Coming Soon in September 2016! 2956 AL PRATTVILLE HIGH POINT TOWN CENTER PRATTVILLE, AL 36066-6542 Coming Soon in September 2016! 2875 AL SPANISH FORT SPANISH FORT TOWN CENTER 22500 TOWN CENTER AVE Coming Soon in September 2016! 2869 AL TRUSSVILLE TUTWILER FARM 5060 PINNACLE SQ Coming Soon in September 2016! 2709 AR FAYETTEVILLE NW ARKANSAS MALL 4201 N SHILOH DR Coming Soon in September 2016! 1961 AR FORT SMITH CENTRAL MALL 5111 ROGERS AVE Coming Soon in September 2016! 2914 AR LITTLE ROCK SHACKLEFORD CROSSING 2600 S SHACKLEFORD RD Coming Soon in July 2016! 663 AR NORTH LITTLE ROCK MC CAIN SHOPPING CENTER 3929 MCCAIN BLVD STE 500 Coming Soon in July 2016! 2879 AR ROGERS PINNACLE HLLS PROMDE 2202 BELLVIEW RD Coming Soon in September 2016! 2936 AZ CASA GRANDE PROMNDE AT CASA GRANDE 1041 N PROMENADE PKWY Coming Soon in September 2016! 157 AZ CHANDLER MILL CROSSING 2180 S GILBERT RD Coming Soon in September 2016! 251 AZ GLENDALE ARROWHEAD TOWNE CENTER 7750 W ARROWHEAD TOWNE CENTER Coming Soon in September 2016! 2842 AZ GOODYEAR PALM VALLEY CORNERST 13333 W MCDOWELL RD Coming Soon in September -

CBL & Associates Properties 2012 Annual Report

COVER PROPERTIES : Left to Right/Top to Bottom MALL DEL NORTE, LAREDO, TX CROSS CREEK MALL, FAYETTEVILLE, NC BURNSVILLE CENTER, BURNSVILLE, MN OAK PARK MALL, KANSAS CITY, KS CBL & Associates Properties, Inc. 2012 Annual When investors, business partners, retailers Report CBL & ASSOCIATES PROPERTIES, INC. and shoppers think of CBL they think of the leading owner of market-dominant malls in CORPORATE OFFICE BOSTON REGIONAL OFFICE DALLAS REGIONAL OFFICE ST. LOUIS REGIONAL OFFICE the U.S. In 2012, CBL once again demon- CBL CENTER WATERMILL CENTER ATRIUM AT OFFICE CENTER 1200 CHESTERFIELD MALL THINK SUITE 500 SUITE 395 SUITE 750 CHESTERFIELD, MO 63017-4841 strated why it is thought of among the best 2030 HAMILTON PLACE BLVD. 800 SOUTH STREET 1320 GREENWAY DRIVE (636) 536-0581 THINK 2012 Annual Report CHATTANOOGA, TN 37421-6000 WALTHAM, MA 02453-1457 IRVING, TX 75038-2503 CBLCBL & &Associates Associates Properties Properties, 2012 Inc. Annual Report companies in the shopping center industry. (423) 855-0001 (781) 398-7100 (214) 596-1195 CBLPROPERTIES.COM HAMILTON PLACE, CHATTANOOGA, TN: Our strategy of owning the The 2012 CBL & Associates Properties, Inc. Annual Report saved the following resources by printing on paper containing dominant mall in SFI-00616 10% postconsumer recycled content. its market helps attract in-demand new retailers. At trees waste water energy solid waste greenhouse gases waterborne waste Hamilton Place 5 1,930 3,217,760 214 420 13 Mall, Chattanooga fully grown gallons million BTUs pounds pounds pounds shoppers enjoy the market’s only Forever 21. COVER PROPERTIES : Left to Right/Top to Bottom MALL DEL NORTE, LAREDO, TX CROSS CREEK MALL, FAYETTEVILLE, NC BURNSVILLE CENTER, BURNSVILLE, MN OAK PARK MALL, KANSAS CITY, KS CBL & Associates Properties, Inc. -

Regional Malls Update SASB Office Stresses November 18, 2020

Regional Malls Update SASB Office Stresses November 18, 2020 ©2020 Morningstar. All Rights Reserved. Delinquent Balance by Vintage No. of Outstanding Delinquent Transactions with Total Outstanding Total Delinquent Delinquency Vintage Loans Transactions Loans Delinquent Loan Pieces Balance Balance Rate % CMBS 1.0 2004-10 25 22 5 5 $ 1,971,189,425 $ 340,381,500 17.3% 2011 36 17 15 10 $ 3,260,894,119 $ 1,069,328,555 32.8% 2012 57 29 14 12 $ 6,931,127,556 $ 1,361,223,563 19.6% 2013 71 49 21 18 $ 10,007,397,698 $ 1,579,944,132 15.8% 2014 54 41 18 20 $ 7,347,007,964 $ 2,724,095,257 37.1% 2015 39 33 8 11 $ 4,483,115,883 $ 529,240,058 11.8% CMBS 2.0 2016 36 50 6 13 $ 6,097,487,560 $ 1,269,971,047 20.8% 2017 23 37 3 4 $ 2,607,603,346 $ 74,006,615 2.8% 2018 20 38 2 4 $ 4,913,120,868 $ 680,652,099 13.9% 2019 13 19 1 1 $ 3,182,443,725 $ 23,500,000 0.7% 2020 3 10 0 0 $ 823,945,946 $ - 0.0% Total 377 345 93 98 $ 51,625,334,090 $ 9,652,342,825 18.7% Source: DBRS Morningstar Viewpoint 2 Maturity Breakdown CMBS Mall Universe CMBS Delinquent Mall Universe 25.00% 20.00% 15.00% 10.00% 5.00% 0.00% 2020 2021 2022 2023 2024 2025 2026 2027 2028 Source: DBRS Morningstar Viewpoint 3 DBRS Morningstar Market Rank Analysis of Delinquent Mall Universe 1.8% 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 1.3% 0.0% 0.0% 17.3% 20.5% 18.5% 40.6% Note: Market Ranks 6 or 8 had no significant delinquency percentages. -

Asheville African American Heritage Architectural Survey

Asheville African American Heritage Architectural Survey Submitted by: Owen & Eastlake LLC P.O. Box 10774 Columbus, Ohio 43201 Table of Contents List of Figures ................................................................................................................................. 3 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 9 Methodology ................................................................................................................................. 10 Historic Overview ......................................................................................................................... 12 Asheville, 1800–1860 ............................................................................................................... 12 Asheville 1865–1898 ................................................................................................................ 14 Jim Crow and Segregation ........................................................................................................ 20 The African American Community Responds .......................................................................... 26 The Boom Ends and the Great Depression ............................................................................... 32 World War II 1940-1945 .......................................................................................................... 37 Post-War, 1945–1965 .............................................................................................................. -

Appalachian Cultural Resources Workshop Papers

Appalachian Cultural Resources Workshop Papers NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Appalachian Cultural Resources Workshop Papers APPALACHIAN Cultural Resources Workshop Papers Papers presented at the workshop held at Owens Hall, University of North Carolina- Asheville on April 1 and 2, 1991 Edited by Ruthanne Livaditis Mitchel 1993 National Park Service, Southeast Regional Office Office of Cultural Resources Cultural Resources Planning Division TABLE OF CONTENTS appalachian/index.htm Last Updated: 30-Sep-2008 http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/sero/appalachian/index.htm[7/12/2012 8:13:52 AM] Appalachian Cultural Resources Workshop Papers (Table of Contents) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Appalachian Cultural Resources Workshop Papers TABLE OF CONTENTS Cover Cover photo from the Blue Ridge Parkway Archives. A 1941 view of Mabry Mill during restoration work. An Overview Of The Workshop Proceedings Ruthanne Livaditis Mitchell Historical Significance Of The Blue Ridge Parkway Ian Firth The Peaks of Otter And The Johnson Farm On The Blue Ridge Parkway Jean Haskell Speer Identification And Preservation Of Nineteenth And Twentieth Century Homesites In The Pisgah and Nantahala National Forests Rodney J. Snedeker and Michael A. Harmon Rural Historic Landscapes And Interpretive Planning On Our Southern National Forests Delce Dyer and Quentin Bass Fish Weirs As Part Of The Cultural Landscape Anne Frazer Rogers Southern Appalachia And The New South Ideal: Asheville As A Case Study In Development Kent Cave Cumberland Homesteads, A Resettlement Community Of -

2016 July Newsletter

Minute-By-Minute is the Monthly Newsletter of the July North Carolina Association of Municipal Clerks 2016 Inside this Issue: President Giblin’s July Message: Asheville 3 Greetings from Omaha, Nebraska!!!!! 2016-17 Nominations 4 And onto Asheville, North Carolina!!!!! BirthdayCalendar 5 Association News 6 The 70th Annual International IIMC Conference was held in Omaha, Nebraska on Sunday, May 22 to Wednesday, May 25, 2016. The North Carolina Asso- IIMC Conference Photos 9 ciation of Municipal Clerks was represented by Melody Shuler and Kathy Queen of Waxhaw, Pam Casey of Rocky Mount, Thelda Rhoney of Valdese, Join NCAMC Lisa Vierling of High Point, Jeanne Giblin of Morehead City and Stephanie Kelly of Charlotte. Know a clerk or deputy clerk who wants to join As President of your organization, I proudly held the North Carolina Flag in the NCAMC? For membership information, email committee Parade of Flags at the Opening Reception. I also participated in a meeting of chair Jim Byrd, CMC, NCCMC the Presidents of the State and International Associations. Many of our chal- of Wilkesboro at the following lenges are the same, unfunded mandates being one of the main concerns. address: Those clerks who have responsibilities for the election process are also ex- [email protected] periencing difficulties with the different qualifications for voters and the voting Now, join IIMC processes in general. The Clerk from Colorado has her own set of problems dealing with legalized marijuana. If you have joined the North Carolina Association of Municipal Clerks and are Under the direction of IIMC Region III District Directors Lynnette Ogden and wondering what else you can Lisa Vierling Region III held a meeting with the clerks from North Carolina, do to grow in your profession, South Carolina, George, Florida and Alabama to keep everyone abreast of the you definitely need to con- sider joining the International functions happening within those state organizations within the Region. -

Medicare Retail Vision Hardware Services

Practice Name Physical Address Physical Address2 Physical City Physical State Physical Zip Physical County Phone Number Group NPI Num 20/20 Eye Care Center 132 Gateway Blvd Mooresville NC 28117 Iredell (704) 664-1124 1588787105 20/20 Vision Express 4111 New Bern Ave. Raleigh NC 27610 Wake (919) 307-3693 1851683262 Accent Optical 1710 South Hawthorne Rd Winston-Salem NC 27103 Forsyth (336) 768-8854 1992932016 America's Best 424 Pinnacle Pkwy, Unit 234 Bristol TN 37620 Sullivan (423) 845-6031 1114383908 America's Best 5343 South Blvd Charlotte NC 28217 Mecklenburg (704) 972-6200 1215491782 America's Best 1216 South Bridford Parkway Suites Q and S Greensboro NC 27407 Guilford (336) 291-1504 1508331448 America's Best 2003 Walnut St Cary NC 27511 Wake (984) 247-8731 1568092641 America's Best 2003 N Eastman Rd, Ste 34 Kingsport TN 37660 Sullivan (423) 408-6134 1609232009 America's Best 401 Cox Road, Ste. 166 Gaston Mall Gastonia NC 28054 Gaston (704) 865-7077 1679848741 America's Best 148 Tunnel Rd Ste 100 Asheville NC 28805 Buncombe (828) 318-0190 1699168542 America's Best 1602 South Stratford Suite 120 Winston-Salem NC 27103 Forsyth (743) 333-5815 1750857413 America's Best 2117 North Main St High Point NC 27262 Guilford (336) 804-6125 1811498793 America's Best 6212 Glenwood Ave., Ste. 101 Raleigh NC 27612 Wake (919) 781-4266 1831437482 America's Best 4434 Fayetteville Rd Raleigh NC 27603 Wake (919) 227-3933 1881167807 America's Best 591 River Hwy Ste P Mooresville NC 28117 Iredell (704) 360-6043 1962997627 America's Best 10420-a Centrum Pkwy Pineville NC 28134 Mecklenburg (704) 540-2811 1982005484 America's Best 3211 Peoples St, Ste 55 Johnson City TN 37604 Warren (423) 328-5189 1992161293 America's Best 1497 Concord Parkway North Concord NC 28025 Cabarrus (704) 706-6715 1992313977 America's Best 14141 Steele Creek Rd Ste 400 Charlotte NC 28273 Mecklenburg (704) 972-9835 1992353825 America's Best 145 Holt Garrison Parkway Coleman Marketplace Danville VA 24540 Pittsylvania (434) 483-2199 1154684496 America's Best 2225 Matthews Township Pkwy Ste. -

P-T Conditions of Selected Samples Across the Blue Ridge Province Breana A

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 1-1-2012 P-T Conditions of Selected Samples Across the Blue Ridge Province Breana A. Felix [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the Geology Commons Recommended Citation Felix, Breana A., "P-T Conditions of Selected Samples Across the Blue Ridge Province" (2012). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Paper 300. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. P-T CONDITIONS OF SELECTED SAMPLES ACROSS THE BLUE RIDGE PROVINCE A thesis submitted to the Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Physical and Applied Science by Breana A. Felix Approved by Dr. Aley El-Shazly Dr. William Niemann Marshall University July 2012 ©2012 Breana A. Felix ALL RIGHTS RESERVED II ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Aley El-Shazly for all the hard work and time he has put into helping me with my thesis. He has been a great mentor and has always looked out for my best interest. Whenever I needed him, he was always there for me and I am really grateful for it. I would also like to acknowledge the rest of the Geology Department for their contribution and funding, along with the students who have supported me and kept me sane.