Appalachian Cultural Resources Workshop Papers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA)

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 07/01/2014 to 09/30/2014 Francis Marion and Sumter National Forests This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact R8 - Southern Region, Occurring in more than one Forest (excluding Regionwide) Chattooga River Boating - Recreation management In Progress: Expected:11/2014 11/2014 James Knibbs Access Notice of Initiation 07/24/2013 803-561-4078 EA Est. Comment Period Public [email protected] Notice 07/2014 Description: The Forest Service is proposing to establish access points for boaters on the Chattooga Wild and Scenic River within the boundaries of three National Forests (Chattahoochee, Nantahala and Sumter). Web Link: http://www.fs.fed.us/nepa/nepa_project_exp.php?project=42568 Location: UNIT - Chattooga River Ranger District, Nantahala Ranger District, Andrew Pickens Ranger District. STATE - Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina. COUNTY - Jackson, Macon, Oconee, Rabun. LEGAL - Not Applicable. Access points for boaters:Nantahala RD - Green Creek; Norton Mill and Bull Pen Bridge; Chattooga River RD - Burrells Ford Bridge; and, Andrew Pickens RD - Lick Log. Southern Region Caves and - Wildlife, Fish, Rare plants Completed Actual: 06/02/2014 07/2014 Dennis Krusac Mine Closures 404-347-4338 CE [email protected] Description: The purpose of the action is to close caves and mines to minimize the transmission potential of white nose -

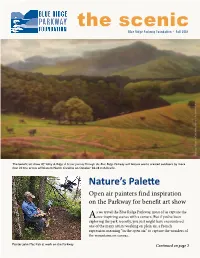

2018 Fall Issue of the Scenic

the scenic Blue Ridge Parkway Foundation - Fall 2018 Painting “Moses H. Cone Memorial Park” by John Mac Kah John Cone Memorial Park” by “Moses H. Painting The benefit art show Of Valley & Ridge: A Scenic Journey Through the Blue Ridge Parkway will feature works created outdoors by more than 20 fine artists of Western North Carolina on October 26-28 in Asheville. Nature’s Palette Open air painters find inspiration on the Parkway for benefit art show s we travel the Blue Ridge Parkway, most of us capture the Aawe-inspiring scenes with a camera. But if you’ve been exploring the park recently, you just might have encountered one of the many artists working en plein air, a French expression meaning “in the open air,” to capture the wonders of the mountains on canvas. Painter John Mac Kah at work on the Parkway Continued on page 2 Continued from page 1 Sitting in front of small easels with brushes and paint-smeared palettes in hand, these artists leave the walls of the studio behind to experience painting amid the landscape and fresh air. The Saints of Paint and Blue Ridge Parkway Foundation are inviting guests on a visual adventure with the benefit art show, Of Valley & Ridge: A Scenic Journey Through the Blue Ridge Parkway, showcasing the works of Western North Carolina fine artists from October 26 to 28 at Zealandia castle in Asheville, North Carolina. The show opens with a ticketed gala from 5 to 8 p.m., Friday, October 26, at the historical Tudor mansion, Zealandia, atop Beaucatcher Mountain. -

TCWP Newsletter No

TENNESSEE CITIZENS FOR WILDERNESS PLP..NNING Newsletter No. 53. February 5, 1973 * concentrate issues x:e.qu::re We depart frOom our usual Newsletter format to on two that your attenticn -- the Bj.g South F k (item 2) and Easterri; Wilde.rness ( ite.m 3) We or Q s t hope this limited a s ignmEnt will encourage many of you to ACT" In a.ddi ion, note the announcement of our next meetingn 1.. HEAD OF WATER POLLUTION AGENCY TO ADDRE3S............ TCWP ---�----------------..,...,. ----�� Time � Weduesda.y" Febru.al·Y 28 i 8: 00 p. me Place: Oak Ridge Civic Center. S ocial Room) Oak Ridge Turnpike (2 blocks east of Highway 1162 intersectic·n) Speaker: Mr. So Lea:ry Jones:� Executive Secre.tary. Tenness�e Water Qu.ality Contt"cl Board about Mrn Jones will talk the workings of the Tennessee Water Quality Control Act i pollu· of 1971 ( c ons dere.d "by ma,ny to be a mo del law), and about ne'W" f€;deral water tion legislationo Many of us are particularly c.oncerned about stripmine discha.rgtas, and Mre Jones has prorolsed to devote time to this tOpiC0 BRING YOUR INTERESTED FRIENDS � 20 BIG SOUTH FORK NATIO�AL RIVER & RECREATIOli AREA .NEEDS SUFPORT On February l� the Senate passed by a vote of 67 :14 the Omnibus Rivers & Harbo1.:'s Act, Section 61 of which creates the 125.000-acre Big S. Fork Natio�al River and Recreation Areao Senator Baker's office cooperated c1o€'ely with cOI ..servation13ts Fork Prese:tvation into of the Big S () Coalition to write the bl11 Sfi:1cingent measun::s, for protecting wilderness of ths g orge s of all streams in the project area� Amend� ments added on the floG'r) at Sen . -

Pisgah Ranger District Terrain, with Many Trails Open to Horses and Ledge, Easy 0.7 Mile Hike from US276

Looking Glass Falls: Photogenic 30ft wide fall Lake Powhatan: Open April-Oct. Offers 98 sites. Trails drops unbroken more than 60ft over a rock cliff, four A limited number with electricity. Trails accessible from Pisgah National Forest miles north of Visitor Center alongside US276. Park campground. Accessible fishing pier. Swimming. Beach. along US276. Overlook and steps to base of falls. Large picnic area. Day-use fee. Showers. Flush toilets. Approximately 120 designated and maintained Dump station. Firewood available. recreation trails covering over 380 miles in the Moore Cove Falls: 50ft waterfall that falls over a district offer a wide variety of difficulty and Pisgah Ranger District terrain, with many trails open to horses and ledge, easy 0.7 mile hike from US276. Go north of Visi- North Mills River: Open year-round. Offers 28 non-motorized bikes. tor Center (1 mile north of Looking Glass Falls). Ap- sites. Some sites on river. Fishing. Adjacent large pic- proaching concrete bridge with adjoining wooden foot- nic area. Day-use fee. Flush toilets (vault toilets in win- Points of Interest bridge and nearby bulletin board, park on paved right ter). Showers (not in winter). Dump station. No water Hunting & Fishing shoulder. Cross footbridge, follow trail upstream. or reservations available in winter. Pisgah Visitor Information Center: Hunting and fishing are allowed on National Courthouse Falls: Courthouse Creek drops 45ft A “must” stop for more Forest lands in accordance with state regula- into a large pool in picturesque cove. Moderate 20 mi- Sunburst: Open April-Oct. Offers 10 sites. Fishing. information about the Dis- tions. -

News Release

Cherokee National Forest 2800 Ocoee Street N. Cleveland, TN 37312 Web: http://fs.usda.gov/cherokee News Release Media Contact: (423) 476-9729 Terry McDonald Wilderness Closure CLEVELAND, TENN (November 12, 2016) – The U.S. Forest Service has implemented a closure for the entire Citico Creek Wilderness and the portion of the Joyce Kilmer-Slickrock Wilderness located in the Cherokee National Forest (Tennessee). This closure has been put in place for public safety due to wild fire activity in the Joyce Kilmer- Slickrock Wilderness in North Carolina. Beginning November 12, 2016, the following restrictions are in place for the Citico Creek Wilderness and the Joyce Kilmer-Slickrock Wilderness within the Cherokee National Forest until further notice: o Closure Pursuant to 36 CFR 261.52(e) – Going into or being upon any area of the Citico Creek Wilderness and Joyce Kilmer-Slickrock Wilderness within the Cherokee National Forest. Cherokee National Forest Supervisor, JaSal Morris said, “The closure of these wilderness areas was necessary for public safety. There is a possibility of the Maple Springs Fire in the Joyce Kilmer-Slickrock Wilderness in North Carolina moving into the Cherokee National Forest. We are closing this area to protect national forest visitors, who may be planning to visit the Citico Creek Wilderness and Joyce Kilmer-Slickrock Wilderness in the Cherokee National Forest, in case the fire moves into that area.” National Forest visitors are asked to obey all state and federal fire related laws and regulations. If you see smoke or suspicious activity contact local fire or law enforcement authorities immediately! -USDA- USDA is an equal opportunity provider, employer and lender. -

America the Beautiful Part 1

America the Beautiful Part 1 Charlene Notgrass 1 America the Beautiful Part 1 by Charlene Notgrass ISBN 978-1-60999-141-8 Copyright © 2020 Notgrass Company. All rights reserved. All product names, brands, and other trademarks mentioned or pictured in this book are used for educational purposes only. No association with or endorsement by the owners of the trademarks is intended. Each trademark remains the property of its respective owner. Unless otherwise noted, scripture quotations are taken from the New American Standard Bible®, Copyright © 1960, 1962, 1963, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1975, 1977, 1995 by the Lockman Foundation. All rights reserved. Used by permission. Cover Images: Jordan Pond, Maine, background by Dave Ashworth / Shutterstock.com; Deer’s Hair by George Catlin / Smithsonian American Art Museum; Young Girl and Dog by Percy Moran / Smithsonian American Art Museum; William Lee from George Washington and William Lee by John Trumbull / Metropolitan Museum of Art. Back Cover Author Photo: Professional Portraits by Kevin Wimpy The image on the preceding page is of Denali in Denali National Park. No part of this material may be reproduced without permission from the publisher. You may not photocopy this book. If you need additional copies for children in your family or for students in your group or classroom, contact Notgrass History to order them. Printed in the United States of America. Notgrass History 975 Roaring River Rd. Gainesboro, TN 38562 1-800-211-8793 notgrass.com Thunder Rocks, Allegany State Park, New York Dear Student When God created the land we call America, He sculpted and painted a masterpiece. -

Cumberland Gap National Historical Park Foundation Document Overview

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE • U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Foundation Document Overview Cumberland Gap National Historical Park Kentucky, Tennessee, and Virginia Contact Information For more information about the Cumberland Gap National Historical Park Foundation Document, contact: [email protected] or (606)248-2817 or write to: Superintendent, Cumberland Gap National Historical Park, 91 Bartlett Park Road, Middlesboro, KY 40965 Purpose Significance Significance statements express why Cumberland Gap National Historical Park resources and values are important enough to merit national park unit designation. Statements of significance describe why an area is important within a global, national, regional, and systemwide context. These statements are linked to the purpose of the park unit, and are supported by data, research, and consensus. Significance statements describe the distinctive nature of the park and inform management decisions, focusing efforts on preserving and protecting the most important resources and values of the park unit. • Crossing the Great Appalachian Barrier. The Cumberland Gap represents a turning point in American history as the Gap witnessed nearly 300,000 settlers pushing through the Appalachian barrier during the late 18th to early 19th century. Today some 40 million Americans can trace their history to crossing through the Gap. • Geology. Cumberland Gap National Historical Park protects an extensive array of geologic features formed over the course of hundreds of millions of years in the wake of numerous Appalachian orogenies (mountain-forming periods). The park’s notable concentration of caves and The purpose of Cumberland Gap karst formations, cliffs, pinnacles, and other geologic national HistoriCal park is to features provide a valuable window into the dynamic nature preserve, protect, and interpret the of the landscape and the impact of geology on human geologic “doorway to the west”—the migration and culture. -

Curt Teich Postcard Archives Towns and Cities

Curt Teich Postcard Archives Towns and Cities Alaska Aialik Bay Alaska Highway Alcan Highway Anchorage Arctic Auk Lake Cape Prince of Wales Castle Rock Chilkoot Pass Columbia Glacier Cook Inlet Copper River Cordova Curry Dawson Denali Denali National Park Eagle Fairbanks Five Finger Rapids Gastineau Channel Glacier Bay Glenn Highway Haines Harding Gateway Homer Hoonah Hurricane Gulch Inland Passage Inside Passage Isabel Pass Juneau Katmai National Monument Kenai Kenai Lake Kenai Peninsula Kenai River Kechikan Ketchikan Creek Kodiak Kodiak Island Kotzebue Lake Atlin Lake Bennett Latouche Lynn Canal Matanuska Valley McKinley Park Mendenhall Glacier Miles Canyon Montgomery Mount Blackburn Mount Dewey Mount McKinley Mount McKinley Park Mount O’Neal Mount Sanford Muir Glacier Nome North Slope Noyes Island Nushagak Opelika Palmer Petersburg Pribilof Island Resurrection Bay Richardson Highway Rocy Point St. Michael Sawtooth Mountain Sentinal Island Seward Sitka Sitka National Park Skagway Southeastern Alaska Stikine Rier Sulzer Summit Swift Current Taku Glacier Taku Inlet Taku Lodge Tanana Tanana River Tok Tunnel Mountain Valdez White Pass Whitehorse Wrangell Wrangell Narrow Yukon Yukon River General Views—no specific location Alabama Albany Albertville Alexander City Andalusia Anniston Ashford Athens Attalla Auburn Batesville Bessemer Birmingham Blue Lake Blue Springs Boaz Bobler’s Creek Boyles Brewton Bridgeport Camden Camp Hill Camp Rucker Carbon Hill Castleberry Centerville Centre Chapman Chattahoochee Valley Cheaha State Park Choctaw County -

Violence and Environmental Stress During the Late Fort Ancient (AD 1425 - 1635) Occupations of Hardin Village

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones 5-1-2019 The Bioarchaeology of Instability: Violence and Environmental Stress During the Late Fort Ancient (AD 1425 - 1635) Occupations of Hardin Village Amber Elaine Osterholt Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Biological and Physical Anthropology Commons Repository Citation Osterholt, Amber Elaine, "The Bioarchaeology of Instability: Violence and Environmental Stress During the Late Fort Ancient (AD 1425 - 1635) Occupations of Hardin Village" (2019). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 3656. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/15778514 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE BIOARCHAEOLOGY OF INSTABILITY: VIOLENCE AND ENVIRONMENTAL STRESS DURING THE LATE FORT ANCIENT (AD 1425 – 1635) OCCUPATIONS -

BLUE RIDGE BIKE PLAN for BUNCOMBE, Haywood, Henderson, Jackson, Madison, Swain, Transylvania Counties - North Carolina Acknowledgments

2013 BLUE RIDGE BIKE PLAN FOR BUNCOMBE, HAYWOOD, HENDERSON, JACKSON, MADISON, SWAIN, TRANSYLVANIA COUNTIES - NORTH CAROLINA ACKNOWLEDGMENTS SPECIAL THANKS Thank you to the more than 600 residents, bicycle shops and clubs, business owners and government employees who participated in meetings, surveys, and regional workgroups. We appreciate all your time and dedication to the development of this plan. STEERING COMMITTEE PROJECT TEAM Susan Anderson, City of Hendersonville Erica Anderson, AICP, Land of Sky Regional Council Paul Benson, Town of Waynesville Jon Beck, Land of Sky Regional Council Lynn Bowles, Madison County John Connell, Land of Sky Regional Council Matt Cable, Henderson County Vicki Eastland, French Broad River MPO Mike Calloway, NC Department of Transportation, Division 13 Christina Giles, Land of Sky Regional Council Claire Carleton, Haywood County Linda Giltz, AICP, Land of Sky Regional Council Kristy Carter, NC Department of Commerce/Appalachian Regional Commission Sarah Graham, Southwestern Commission Nathan Clark, Haywood County Josh King, AICP, Land of Sky RPO Daniel Cobb, City of Brevard Don Kostelec, AICP, Kostelec Planning, LLC Chris Cooper, Jackson County Philip Moore, Southwestern RPO Lucy Crown, Buncombe County Natalie Murdock, Land of Sky RPO Jill Edwards, Town of Black Mountain John Vine-Hodge, NC DOT, Division of Bicycle and Carolyn Fryberger, Town of Black Mountain Pedestrian Transportation Gerald Green, Jackson County Lyuba Zuyeva, French Broad River MPO Jessica Hocz, Madison County Preston Jacobsen, Haywood -

Asheville and Buncombe County

.1 (? Collection of American ILiteratur^ Ikqucatfjeb to Cfje ilibrarp of ttje Hnibersitp of i^ortf) Carolina "He gave back as rain that which he ^>^ receiveei as mist" D97/. !/-S7,9 00032761146 FOR USE ONLY IN THE NORTH CAROLINA COLLECTION w^ r I . \ STATEMENT November of last year The Asheville Citizen moved into its new INand permanent home at No. 25 Haywood Street. In celebration of that event The Citizen published a special edition, in which appeared two most interesting and highly instructive articles on the history of Western North Carolina and of Buncombe County, one prepared by Dr. F. A. Sondley, and the other by General Theodore F. Davidson, These two articles attracted widespread attention as they both narrated incidents and facts, many of which had never before been printed, and many of The Citizen's readers urged tliat these two articles be reprinted in pamphlet form, so as to be more easily read and pre- served for the future. At our request Dr. Sondley and General Davidson have both revised those two articles and have brought them up to date, and, in response to this request. The Citizen has had them printed and bound in this little volume. The Citizen believes that the public will be deeply interested in the facts set forth in this little volume, and is glad to have the oppor- tunity^ of performing what it believes is a great public service in hand- ing them down for future generations. The expense of securing the illustrations and the printing of this volume is considerably more than the . -

Blue Ridge Parkway Facilities for Swimming Are Available in Nearby U.S

blue ridge parkway Facilities for swimming are available in nearby U.S. Forest Service recreation areas, State parks, and blue ridge north Carolina mountain resorts. The lakes and ponds along the parkway are for fishing and scenic beauty; they are parkway Virginia not suitable for swimming. Boats without motor or sail are permitted on Price Lake, but boats are not permitted on any other Blue Ridge Parkway, a unit of the National Park parkway waters. System, extends 469 miles through the southern Ap palachians, past vistas of quiet natural beauty and Help protect the parkway. This is your parkway. rural landscapes lightly shaped by the activities of Help us in protecting it. Leave shrubs and wild- man. Designed especially for motor recreation, the flowers for others to enjoy. Drive carefully. Speed parkway provides quiet, leisurely travel, free from SUMMIT OF SHARP TOP, PEAKS OF OTTER LOOKING GLASS ROCK, MILE 417 THE FENCES, GROUNDHOG MOUNTAIN, MILE 188.8 HIGHLAND MEADOWS, DOUGHTON PARK MILE HIGH OVERLOOK , MILE 458.2 PURGATORY MOUNTAIN, MILE 92.2 limit is 45 miles per hour. Report any accident to commercial development and congestion of high-speed Fishing. Streams and lakes along the parkway are a park ranger. Vehicles being used commercially highways. No ordinary road, it follows mountain written on the face of this land where crops and talks, museum and roadside exhibits, and other Autumn brings color in late September when dog Visitor-use areas are marked by this Rocky Knob and Mount Pisgah campgrounds. Each emblem. In them may be located picnic primarily trout waters.