1457313988B8400d.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Differences Between Local Residents' and Visitors' Environmental

Differences between Local Residents’ and Visitors’ Environmental Per- ception of Landscape Change of Rural Communities in Taiwan Chun-Wei Tsou*, Sheng-Jung Ou *Department of Landscape Architecture, Tunghai University; No.1727, Sec. 4, Taiwan Boulevard, Taichung 40704, Taiwan; +886.4.2359.0417, [email protected] Abstract Rural community development on landscape environment has become a hot issue in making rural travel attractions and this development phenomenon is getting popular in Taiwan. Visitors’ environmental per- ception on rural landscape environment would affect their behavior, impressions, and willingness-to-re- turn about that rural area. Therefore, residents and visitors who travelled in the top ten rural villages of Taiwan elected in 2007 were subjects in this research in order to analyze differences between local resi- dents’ and visitors’ environmental perception of landscape change of rural communities. Three factors, perception on rural environmental change, perception on rural environmental characteristic, and percep- tion on life emotion about rural environment, were extracted after exploratory factor analysis was done on acceptability of perception on community landscape environment of all subjects. The result of this research could act as references for management of landscape environment in developing rural commu- nities. It is expected that numerous difference could be avoided between development goals of rural communities and visitors’ perception on landscape environment. Keywords: Rural community, Local resident, Visitor, Environmental perception 161 1.Introduction type of Innovative Agriculture; the type of General The development of rural communities and rural Prosperity and Beauty; the type of Economic Pro- and agricultural land use have always been poli- duction; and the type of Aboriginal Life Style. -

The History and Politics of Taiwan's February 28

The History and Politics of Taiwan’s February 28 Incident, 1947- 2008 by Yen-Kuang Kuo BA, National Taiwan Univeristy, Taiwan, 1991 BA, University of Victoria, 2007 MA, University of Victoria, 2009 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of History © Yen-Kuang Kuo, 2020 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This dissertation may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee The History and Politics of Taiwan’s February 28 Incident, 1947- 2008 by Yen-Kuang Kuo BA, National Taiwan Univeristy, Taiwan, 1991 BA, University of Victoria, 2007 MA, University of Victoria, 2009 Supervisory Committee Dr. Zhongping Chen, Supervisor Department of History Dr. Gregory Blue, Departmental Member Department of History Dr. John Price, Departmental Member Department of History Dr. Andrew Marton, Outside Member Department of Pacific and Asian Studies iii Abstract Taiwan’s February 28 Incident happened in 1947 as a set of popular protests against the postwar policies of the Nationalist Party, and it then sparked militant actions and political struggles of Taiwanese but ended with military suppression and political persecution by the Nanjing government. The Nationalist Party first defined the Incident as a rebellion by pro-Japanese forces and communist saboteurs. As the enemy of the Nationalist Party in China’s Civil War (1946-1949), the Chinese Communist Party initially interpreted the Incident as a Taiwanese fight for political autonomy in the party’s wartime propaganda, and then reinterpreted the event as an anti-Nationalist uprising under its own leadership. -

![[カテゴリー]Location Type [スポット名]English Location Name [住所](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8080/location-type-english-location-name-1138080.webp)

[カテゴリー]Location Type [スポット名]English Location Name [住所

※IS12TではSSID"ilove4G"はご利用いただけません [カテゴリー]Location_Type [スポット名]English_Location_Name [住所]Location_Address1 [市区町村]English_Location_City [州/省/県名]Location_State_Province_Name [SSID]SSID_Open_Auth Misc Hi-Life-Jingrong Kaohsiung Store No.107 Zhenxing Rd. Qianzhen Dist. Kaohsiung City 806 Taiwan (R.O.C.) Kaohsiung CHT Wi-Fi(HiNet) Misc Family Mart-Yongle Ligang Store No.4 & No.6 Yongle Rd. Ligang Township Pingtung County 905 Taiwan (R.O.C.) Pingtung CHT Wi-Fi(HiNet) Misc CHT Fonglin Service Center No.62 Sec. 2 Zhongzheng Rd. Fenglin Township Hualien County Hualien CHT Wi-Fi(HiNet) Misc FamilyMart -Haishan Tucheng Store No. 294 Sec. 1 Xuefu Rd. Tucheng City Taipei County 236 Taiwan (R.O.C.) Taipei CHT Wi-Fi(HiNet) Misc 7-Eleven No.204 Sec. 2 Zhongshan Rd. Jiaoxi Township Yilan County 262 Taiwan (R.O.C.) Yilan CHT Wi-Fi(HiNet) Misc 7-Eleven No.231 Changle Rd. Luzhou Dist. New Taipei City 247 Taiwan (R.O.C.) Taipei CHT Wi-Fi(HiNet) Restaurant McDonald's 1F. No.68 Mincyuan W. Rd. Jhongshan District Taipei CHT Wi-Fi(HiNet) Restaurant Cobe coffee & beauty 1FNo.68 Sec. 1 Sanmin Rd.Banqiao City Taipei County Taipei CHT Wi-Fi(HiNet) Misc Hi-Life - Taoliang store 1F. No.649 Jhongsing Rd. Longtan Township Taoyuan County Taoyuan CHT Wi-Fi(HiNet) Misc CHT Public Phone Booth (Intersection of Sinyi R. and Hsinsheng South R.) No.173 Sec. 1 Xinsheng N. Rd. Dajan Dist. Taipei CHT Wi-Fi(HiNet) Misc Hi-Life-Chenhe New Taipei Store 1F. No.64 Yanhe Rd. Anhe Vil. Tucheng Dist. New Taipei City 236 Taiwan (R.O.C.) Taipei CHT Wi-Fi(HiNet) Misc 7-Eleven No.7 Datong Rd. -

Natural History and Rearing Technique for Trictenotoma Formosana Kriesche, 1919 (Coleoptera: Trictenotomidae)

臺灣研蟲誌 Taiwanese Journal of Entomological Studies 4(1): 1-8 (2019) [研究文章 Research Article] http://zoobank.org/urn:zoobank.org:pub:5C6ECD7A-9B80-4F2D-99BC-97D6FF912C26 Unravel the Century-old Mystery of Trictenotomidae: Natural History and Rearing Technique for Trictenotoma formosana Kriesche, 1919 (Coleoptera: Trictenotomidae) ZONG-RU LIN1, FANG-SHUO HU2, † 1 No.321, Changchun St., Wuri Dist., Taichung City 414, Taiwan. 2 Department of Entomology, National Chung Hsing University, No. 145, Xingda Rd., South Dist., Taichung City 402, Taiwan. † Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract: This paper reports the detailed biological information of Taiwanese Trictenotoma formosana Kriesche, 1919 involving its natural history, life cycle, rearing technique, and observations under artificial conditions, which is the first study of Trictenotomidae. Both larval diet and adult habits are also addressed. Further life cycle observations including photographs of larval group, feeding situation of adults and larvae, the tunnel built by the larva, pupal cell and newly eclosed adult are also provided. Key words: Trictenotomidae, Trictenotoma, natural history, rearing technique, larva Introduction The family Trictenotomidae Blanchard, 1845, a small group in Tenebrionoidea consisting of only two genera and fifteen species (Telnov, 1999; Drumont, 2006; Drumont, 2016), distributes in the Oriental and southeastern Palearctic regions. Though trictenotomids are large and conspicuous beetles and even very common in insect specimen markets, its natural history is less known. In Trictenotomidae, all species are forest inhabitants and adults are known to be active nocturnally and are collected easily by light attraction (Pollock & Telnov, 2010). Gahan (1908) provided a description of the mature larva of Trictenotoma childreni Gray which only mentioned that it was found with the debris of pupae and imagines but without detail about microhabitat. -

To Meet Same-Day Flight Cut-Off Time and Cut-Off Time for Fax-In Customs Clearance Documents

Zip Same Day Flight No. Area Post Office Name Telephone Number Address Code Cut-off time* (03)5215-984 1 Hsinchu/ Miaoli Hsinchu Wuchang St. Post Office 300 No. 81, Wuchang St., East District, Hsinchu 300-41, Taiwan (R.O.C.) 14:30 (03)5250-760 2 Hsinchu/ Miaoli Hsinchu Dongmen Post Office 300 (03)5229-044 No. 56, Dongmen St., East District, Hsinchu 300-41, Taiwan (R.O.C.) 13:10 National Tsinghua University Post 3 Hsinchu/ Miaoli 300 (03)5717-086 No. 99, Sec. 2, Guangfu Rd., East District, Hsinchu 300-71, Taiwan (R.O.C.) 14:00 Office 4 Hsinchu/ Miaoli Hsinchu Fujhongli Post Office 300 (03)5330-441 No. 452-1, Sec. 1, Jingguo Rd., East District, Hsinchu 300-59, Taiwan (R.O.C.) 13:30 5 Hsinchu/ Miaoli Hsinchu Guanghua St. Post Office 300 (03)5330-945 No. 87, Guanghua N. St., N. District, Hsinchu 300-53, Taiwan (R.O.C.) 13:10 6 Hsinchu/ Miaoli Hsinchu Neihu Rd. Post Office 300 (03)5374-709 No.68, Neihu Rd., Xiangshan Dist., Hsinchu City 300-94, Taiwan (R.O.C.) 09:10 7 Hsinchu/ Miaoli Hsinchu Yingming St. Post Office 300 (03)5238-365 No. 10, Yingming St., N. District, Hsinchu 300-42, Taiwan (R.O.C.) 13:10 8 Hsinchu/ Miaoli Hsinchu Guandong Bridge Post Office 300 (03)5772-024 No. 313, Sec. 1, Guangfu Rd., East District, Hsinchu 300-74, Taiwan (R.O.C.) 14:00 9 Hsinchu/ Miaoli Hsinchu Shulintou Post Office 300 (03)5310-204 No. 449, Sec. 2, Dongda Rd., N. -

Liv Round-The-Island Fun / from Taipei (10 Days & 9 Nights)

Liv Round-the-Island Fun / From Taipei (10 days & 9 nights) A cycling tour that only belongs to females… Time and speed, we decide Comprehensive tour choices, to realize the dream of cycling around Taiwan Hop on the bike and enjoy! 【Total Trip Distance: 912 KM Average Speed Per Hour: Approx. 20-25 KM】 Taipei→Hsinchu ~ Taipei LIV Shop-Sanxia-Daxi-Shimen Xindian-Daxi-Guanxi-Hsinchu Provincial Highway No. 9 + County Highway Distance 100 KM No. 110 + Provincial Highway No. 3 【Pick-up Location】7:00 a.m. Taipei Liv Shop 【No.309, Dunhua N. Rd., Songshan Dist., Taipei City】 Leaving the hustle and bustle west, we ride on the tracks in the woods to avoid the busy traffic. Today we challenge ourselves with Provincial Highway No. 3. Without much slope, we still need to ride with a bit caution. The persistence would pay off when we enjoy the nice views. Today we visit Daxi Old Street, and experience the joy brought by seniors’ wisdom. Day1 Daxi Old Street: It’s the hometown of dry bean curd, with Highlights hand-made traditional taste. Made with whole hearted efforts, it’s so delicious that you can’t miss. There’s also a great street artist here, performing traditional whipping top. Only fortunate visitors could get the chance to see it. Hsinchu City God Temple: The Temple, located at Hsinchu City, is classified as a third-class historic site. In 1891, Master Chang in Qing Dynasty predicted a major catastrophe, and the City God Temple was suggested to be the worship ceremony location by local celebrity. -

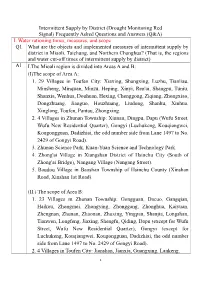

Intermittent Supply by District (Drought Monitoring Red Signal) Frequently Asked Questions and Answers (Q&A) I

Intermittent Supply by District (Drought Monitoring Red Signal) Frequently Asked Questions and Answers (Q&A) I. Water rationing times, measures, and scope Q1 What are the objects and implemented measures of intermittent supply by district in Miaoli, Taichung, and Northern Changhua? (That is, the regions and water cut-off times of intermittent supply by district) A1 I.The Mioali region is divided into Areas A and B: (I)The scope of Area A: 1. 29 Villages in Toufen City: Xiaxing, Shangxing, Luzhu, Tianliau, Minsheng, Minquan, Minzu, Heping, Xinyi, Ren'ai, Shangpu, Tuniu, Shanxia, Wenhua, Douhuan, Hexing, Chenggong, Ziqiang, Zhongxiao, Dongzhuang, Jianguo, Houzhuang, Liudong, Shanhu, Xinhua, Xinglong, Toufen, Pantau, Zhongxing. 2. 4 Villages in Zhunan Township: Xinnan, Dingpu, Dapu (Wufu Street, Wufu New Residential Quarter), Gongyi (Luchukeng, Kouqiangwei, Kougongguan, Dadizhiai, the odd number side from Lane 1497 to No. 2429 of Gongyi Road). 3. Zhunan Science Park, Kuan-Yuan Science and Technology Park. 4. Zhong'ai Village in Xiangshan District of Hsinchu City (South of Zhong'ai Bridge), Nangang Village (Nangang Street). 5. Baudou Village in Baoshan Township of Hsinchu County (Xinshan Road, Xinshan 1st Road). (II.) The scope of Area B: 1. 23 Villages in Zhunan Township: Gongguan, Dacuo, Gangqian, Haikou, Zhongmei, Zhongying, Zhonggang, Zhonghua, Kaiyuan, Zhengnan, Zhunan, Zhaonan, Zhuxing, Yingpan, Shanjia, Longshan, Tianwen, Longfeng, Jiaxing, Shengfu, Qiding, Dapu (except for Wufu Street, Wufu New Residential Quarter), Gongyi (except for Luchukeng, Kouqiangwei, Kougongguan, Dadizhiai, the odd number side from Lane 1497 to No. 2429 of Gongyi Road). 2. 4 Villages in Toufen City: Jianshan, Jianxia, Guangxing, Lankeng. 1 3. Zhunan Industrial Park, Toufen Industrial Park. -

The Irresistible Aromas of Taiwan

The Irresistible The many permutations of Taiwan tea Aromas of Tea is an indispensable part of life in Taiwan, one of the "seven door and manganese, along with trace elements, vitamins, A multitude of tea products Taiwan Tea openers: firewood, rice, cooking oil, salt, soy sauce, vinegar, and tea." and other elements needed by the body. Tea is more than a natural health beverage for drinking; it can also be In addition to drinking tea and eating tea cuisine, you Besides all this, as a gourmet you will also want added to food and made into local snacks such as tea-boiled eggs, and can also choose other tea products to take home as gifts to experience Taiwan’s unique tea cuisine. Tea can Taiwan has long been known among the countries of the East as the "land of tea," and in fact the eaten. It can even be used to produce beauty products. In Taiwan you that will enchant your friends. Yes indeed, tea leaves are eliminate oiliness, eradicate gamey flavors, refresh island is the world’s foremost producer of semi-fermented tea. Back a century and a half ago the must not miss the uniquely Taiwanese, richly diverse culture of tea. good for more than just making a beverage. They can be the taste buds, and intensify tastes, and so makes island became famous for its "Formosa Oolong (Wulong) Tea"; its unique "White-tip Wulong" even made into tea jelly, fruit tea, tea candy, and other items, a fine additive to food. Different varieties of tea have caught the attention of Queen Victoria, who is said to have dubbed it "Oriental Beauty." In recent and their essence can be extracted to produce such different characteristics, and they have a variety of years new varieties such as Taiwan No. -

Family Gender by Club MBR0018

Summary of Membership Types and Gender by Club as of November, 2013 Club Fam. Unit Fam. Unit Club Ttl. Club Ttl. Student Leo Lion Young Adult District Number Club Name HH's 1/2 Dues Females Male Total Total Total Total District 300 G1 23366 CHU NAN 19 19 23 43 0 0 0 66 District 300 G1 23372 HSINCHU 0 0 1 56 0 0 0 57 District 300 G1 23373 HSINCHU CENTRAL 18 18 23 115 0 0 0 138 District 300 G1 23385 MIAOLI 3 8 3 41 0 0 0 44 District 300 G1 32831 TOUFEN 2 7 6 40 0 0 0 46 District 300 G1 33458 YUAN LI L C 0 0 1 23 0 0 0 24 District 300 G1 34405 HSINCHU CHENG KUNG 0 0 2 29 0 0 0 31 District 300 G1 36500 TUNG HSIAO 0 0 0 24 0 0 0 24 District 300 G1 37711 HSINCHU HSIEN CHU TUNG 0 0 5 21 0 0 0 26 District 300 G1 38871 HSINCHU CHUNG CHENG L C 0 0 0 41 0 0 0 41 District 300 G1 39741 CHUTUNG CHUNG HSIN L C 0 0 4 16 0 0 0 20 District 300 G1 39913 HSIN PU VILLAGE L C 15 17 22 24 0 0 0 46 District 300 G1 40325 HSINCHU PEI PU 1 1 3 14 0 0 0 17 District 300 G1 40377 HSIN FENG L C 9 22 14 60 0 0 0 74 District 300 G1 40543 CHUPEI L C 4 10 8 71 0 0 0 79 District 300 G1 40545 KWANHSI L C 20 26 26 40 0 0 0 66 District 300 G1 41051 CHIUNGLIN 10 10 12 16 0 0 0 28 District 300 G1 41389 HOULUNG L C 0 0 2 51 0 0 0 53 District 300 G1 42451 HSINCHU CHUNG SHAN 15 15 15 24 0 0 0 39 District 300 G1 42578 MIAOLI CENTRAL 5 5 3 35 0 0 0 38 District 300 G1 42855 HSINCHU HENGSHAN 9 9 9 12 0 0 0 21 District 300 G1 43167 HSINCHU KUANG HWA 42 46 41 98 0 0 0 139 District 300 G1 43383 KUNGKUAN 13 13 13 41 0 0 0 54 District 300 G1 43790 HSINCHU OMEI 0 0 7 22 0 0 0 29 District -

Passport Template

ANNEX R – PASSPORT TEMPLATE CONTENTS A. Project title B. Project description C. Proof of project eligibility D. Unique Project Identification E. Outcome stakeholder consultation process F. Outcome sustAinAbility assessment G. Sustainability monitoring plan H. Additionality and conservativeness deviations Annex 1 ODA declarations SECTION A. Project Title [See Toolkit 1.6] Title: InfraVest Taiwan Wind Farms Bundled Project 2012 Date: 21/06/2016 Version no.: 4.0 SECTION B. Project description [See Toolkit 1.6] InfraVest Taiwan Wind Farms Bundled Project 2012 is constructed and operated by InfraVest Wind Group. The project in total comprises 34 wind turbines, each having a capacity up to 2.3 MW. The total installed capacity of the proposed project is 78.2 MW. At full capacity, the output of the project is totally expected to be 187,680 MWh per year derived from the FSRs of each sub-project. The annual emission reductions are estimated as about 126,120 tCO2e/year. The project start date is 13/12/20121. InfraVest Taiwan Wind Farms Bundled Project 2012 is a bundle project: 1. Chubei Wind Farm Project: a 11.5 MW onshore wind farm in Chubei township, Hsinchu County, which comprises 5 wind turbines. The annual electricity generated is 27,600 MWh with emission reductions of 18,547 t CO2e/year. 2. Zhaowei Wind Farm Project: a 13.8 MW onshore wind farm in Tongxiao Township, Miaoli County,which comprises 6 wind turbines. The annual electricity generated is 33,120 MWh with emission reductions of 22,257 t CO2e/year. 3. Tongyuan Wind Farm Project: a 52.9 MW onshore wind farm located in Tongxiao & Yuanli Township, Miaoli County, comprised 23 wind turbines. -

Evidence for Range Expansion and Origins of an Invasive Hornet Vespa Bicolor (Hymenoptera, Vespidae) in Taiwan, with Notes on Its Natural Status

insects Article Evidence for Range Expansion and Origins of an Invasive Hornet Vespa bicolor (Hymenoptera, Vespidae) in Taiwan, with Notes on Its Natural Status Sheng-Shan Lu 1, Junichi Takahashi 2, Wen-Chi Yeh 1, Ming-Lun Lu 3,*, Jing-Yi Huang 3, Yi-Jing Lin 4 and I-Hsin Sung 4,* 1 Taiwan Forestry Research Institute, Council of Agriculture, Executive Yuan, Taipei City 100051, Taiwan; [email protected] (S.-S.L.); [email protected] (W.-C.Y.) 2 Faculty of Life Sciences, Kyoto Sangyo University, Kyoto City 603-8555, Japan; [email protected] 3 Endemic Species Research Institute, Council of Agriculture, Executive Yuan, Nantou County 552203, Taiwan; [email protected] 4 Department of Plant Medicine, National Chiayi University, Chiayi City 600355, Taiwan; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (M.-L.L.); [email protected] (I-H.S.) Simple Summary: The invasive hornet Vespa bicolor Fabricius was first discovered in Taiwan in 2003 and was not confirmed to have been established until 2014. This study was conducted in order to (1) assess the current status of V. bicolor abundance, dispersal, seasonality, and possible impact on honeybee (Apis mellifera Linnaeus) in Taiwan; (2) and to trace the origins of Taiwan’s V. bicolor population. To assess V. bicolor abundance, we used visual surveys, sweep netting, and hornet traps in four known ranges in northern and central Taiwan from 2016 to 2020. Additionally, to understand V. bicolor dispersion, we mapped environmental data using ArcGIS, and to predict future V. bicolor range, we used ecological niche modeling. -

Non-Anopheline Mosquitoes of Taiwan: Annotated Catalog and Bibliography1

Pacific Insects 4 (3) : 615-649 October 10, 1962 NON-ANOPHELINE MOSQUITOES OF TAIWAN: ANNOTATED CATALOG AND BIBLIOGRAPHY1 By J. C. Lien TAIWAN PROVINCIAL MALARIA RESEARCH INSTITUTE2 INTRODUCTION The studies of the mosquitoes of Taiwan were initiated as early as 1901 or even earlier by several pioneer workers, i. e. K. Kinoshita, J. Hatori, F. V. Theobald, J. Tsuzuki and so on, and have subsequently been carried out by them and many other workers. Most of the workers laid much more emphasis on anopheline than on non-anopheline mosquitoes, because the former had direct bearing on the transmission of the most dreaded disease, malaria, in Taiwan. Owing to their efforts, the taxonomic problems of the Anopheles mos quitoes of Taiwan are now well settled, and their local distribution and some aspects of their habits well understood. However, there still remains much work to be done on the non-anopheline mosquitoes of Taiwan. Nowadays, malaria is being so successfully brought down to near-eradication in Taiwan that public health workers as well as the general pub lic are starting to give their attention to the control of other mosquito-borne diseases such as filariasis and Japanese B encephalitis, and the elimination of mosquito nuisance. Ac cordingly extensive studies of the non-anopheline mosquitoes of Taiwan now become very necessary and important. Morishita and Okada (1955) published a reference catalogue of the local non-anophe line mosquitoes. However the catalog compiled by them in 1955 was based on informa tion obtained before 1945. They listed 34 species, but now it becomes clear that 4 of them are respectively synonyms of 4 species among the remaining 30.