Water Resources and Sanitation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SHIVAJI UNIVERSITY, KOLHAPUR Provisional Electoral Roll of Registered Graduates

SHIVAJI UNIVERSITY, KOLHAPUR Provisional Electoral Roll of Registered Graduates Polling Center : 1 Kolhapur District - Chh.Shahu Central Institute of Business Education & Research, Kolhapur Faculty - ARTS AND FINE ARTS Sr. No. Name and Address 1 ADAKE VASANT SAKKAPPA uchgaon kolhapur 416005, 2 ADNAIK DEVRAJ KRISHNAT s/o krishnat adnaik ,891,gaalwada ,yevluj,kolhapur., 3 ADNAIK DEVRAJ KRUSHANT Yevluj Panhala, 4 ADNAIK KRISHNAT SHANKAR A/P-KUDITRE,TAL-KARVEER, City- KUDITRE Tal - KARVEER Dist- KOLHAPUR Pin- 416204 5 AIWALE PRAVIN PRAKASH NEAR YASHWANT KILLA KAGAL TAL - KAGAL. DIST - KOLHAPUR PIN - 416216, 6 AJAGEKAR SEEMA SHANTARAM 35/36 Flat No.103, S J Park Apartment, B Ward Jawahar Nagar, Vishwkarma Hsg. Society, Kolhapur, 7 AJINKYA BHARAT MALI Swapnanjali Building Geetanjali Colony, Nigave, Karvir kolhapur, 8 AJREKAR AASHQIN GANI 709 C WARD BAGAWAN GALLI BINDU CHOUK KOLHAPUR., 9 AKULWAR NARAYAN MALLAYA R S NO. 514/4 E ward Shobha-Shanti Residency Kolhapur, 10 ALAVEKAR SONAL SURESH 2420/27 E ward Chavan Galli, Purv Pavellion Ground Shejari Kasb bavda, kolhapur, 11 ALWAD SANGEETA PRADEEP Plot No 1981/6 Surna E Ward Rajarampuri 9th Lane kolhapur, 12 AMANGI ROHIT RAVINDRA UJALAIWADI,KOLHAPUR, 13 AMBI SAVITA NAMDEV 2362 E WARD AMBE GALLI, KASABA BAWADA KOLHPAUR, 14 ANGAJ TEJASVINI TANAJI 591A/2 E word plot no1 Krushnad colony javal kasaba bavada, 15 ANURE SHABIR GUJBAR AP CHIKHALI,TAL KAGAL, City- CHIKALI Tal - KAGAL Dist- KOLHPUR Pin- 416235 16 APARADH DHANANJAY ASHOK E WARD, ULAPE GALLI, KASABA BAWADA, KOLHAPUR., 17 APUGADE RAJENDRA BAJARANG -

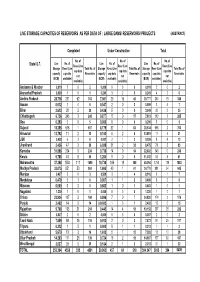

Live Storage Capacities of Reservoirs As Per Data of : Large Dams/ Reservoirs/ Projects (Abstract)

LIVE STORAGE CAPACITIES OF RESERVOIRS AS PER DATA OF : LARGE DAMS/ RESERVOIRS/ PROJECTS (ABSTRACT) Completed Under Construction Total No. of No. of No. of Live No. of Live No. of Live No. of State/ U.T. Resv (Live Resv (Live Resv (Live Storage Resv (Live Total No. of Storage Resv (Live Total No. of Storage Resv (Live Total No. of cap data cap data cap data capacity cap data Reservoirs capacity cap data Reservoirs capacity cap data Reservoirs not not not (BCM) available) (BCM) available) (BCM) available) available) available) available) Andaman & Nicobar 0.019 20 2 0.000 00 0 0.019 20 2 Arunachal Pradesh 0.000 10 1 0.241 32 5 0.241 42 6 Andhra Pradesh 28.716 251 62 313 7.061 29 16 45 35.777 280 78 358 Assam 0.012 14 5 0.547 20 2 0.559 34 7 Bihar 2.613 28 2 30 0.436 50 5 3.049 33 2 35 Chhattisgarh 6.736 245 3 248 0.877 17 0 17 7.613 262 3 265 Goa 0.290 50 5 0.000 00 0 0.290 50 5 Gujarat 18.355 616 1 617 8.179 82 1 83 26.534 698 2 700 Himachal 13.792 11 2 13 0.100 62 8 13.891 17 4 21 J&K 0.028 63 9 0.001 21 3 0.029 84 12 Jharkhand 2.436 47 3 50 6.039 31 2 33 8.475 78 5 83 Karnatka 31.896 234 0 234 0.736 14 0 14 32.632 248 0 248 Kerala 9.768 48 8 56 1.264 50 5 11.032 53 8 61 Maharashtra 37.358 1584 111 1695 10.736 169 19 188 48.094 1753 130 1883 Madhya Pradesh 33.075 851 53 904 1.695 40 1 41 34.770 891 54 945 Manipur 0.407 30 3 8.509 31 4 8.916 61 7 Meghalaya 0.479 51 6 0.007 11 2 0.486 62 8 Mizoram 0.000 00 0 0.663 10 1 0.663 10 1 Nagaland 1.220 10 1 0.000 00 0 1.220 10 1 Orissa 23.934 167 2 169 0.896 70 7 24.830 174 2 176 Punjab 2.402 14 -

Avifauna and Comparative Study of Threatened Birds at Urban Wetlands of Kolhapur, Maharashtra, India

Int. J. of Life Sciences, 2017, Vol. 5 (4): 649-660 ISSN: 2320-7817| eISSN: 2320-964X RESEARCH ARTICLE Avifauna and Comparative Study of Threatened Birds at Urban Wetlands of Kolhapur, Maharashtra, India Patil Nachiket Suryakant Department of Environment Science, Shivaji University, Kolhapur-416 004, Maharashtra, India Email: - [email protected] | (+918805835153) Manuscript details: ABSTRACT Received: 28. 10.2017 Kolhapur is blessed with numbers of wetlands which is productive and Accepted: 05.12.2017 unique ecosystem that support number of birds. The present study focus on Published : 31.12.2017 avifaunal diversity and population status of threatened bird species by Diversity indices at in and around the wetlands of Kolhapur from 2016- Editor: 2017. Bird survey was conducted according to line transect method and Dr. Arvind Chavhan standard point count method. Species Diversity indices and Simpson index were used for statistical analysis. A total of 159 species of birds belonging to Cite this article as: 17 orders and 60 families were recorded, of those 109 species of terrestrial Patil Nachiket Suryakant (2017) birds and 50 species of water birds were observed. Out of 159 birds, 93 Avifauna and Comparative Study of Threatened Birds at Urban Wetlands residential, 50 residential migratory and 15 are migratory. Of those one of Kolhapur, Maharashtra, India; species is vulnerable, three species near threatened were observed. Among International J. of Life Sciences, 5 (4): the birds recorded in study area, about 43% were insectivores and other 649-660. dominating types include mixed diet 10%, piscivores 15%, omnivores 9%, carnivores 9%, granivores 9%, fructivores 2% and nectivores 3% Acknowledgement respectively. -

09 Chapter 3.Pdf

CHAPTER ID IDENTIFICATION OF THE TOURIST SPOT 3.1The Kolhapur City 3.2 Geographical Location 3.3 History 3.4 Significance of Kolhapur for the Study [A] Aspects and Outlying belts [B] Hill top konkan and the plain [C] Hills [D] Rive [E] Ponds and lakesrs [F] Geology [G] Climate [H] Forests [I] Flora of Kolhapur District [J] Vegetation [K] Grassland [L] Economically important plants [P] Wild Animals [Q] Fishers 3.5 Places of Interest in the selected area and their Ecological Importance. 1. New Palace 2. Rankala Lake 3. The Shalini Palace 4. Town Hall 5. Shivaji University 6. Panctiaganga Ghat 7. Mahalaxmi Temple 8. Temblai Hill Temple Garden 9. Gangawesh Dudh Katta 3.6 Place of Interest around the Kolhapur / Selected area and their ecological importance. 1. Panhala Fort 2. Pawankhind and Masai pathar 3. Vishalgad 4. Gaganbavada / Gagangad 5. Shri Narsobachi Wadi 6. Khirdrapnr: Shri Kopeshwar t«pk 7. Wadi Ratnagh-i: Shri Jyotiba Tmepie 8. Shri BahobaM Temple 9. RaAaatgiii and Dajqror Forest Reserves 10. Dob wade falls 11. Barld Water Fails 12. Forts 13. Ramteeth: 14. Katyayani: 15 The Kaneri Math: 16 Amba Pass 3.7 misceieneoas information. CHAPTER -HI IDENTIFICATION OF THE TOURIST SPOT. The concept of Eco-Tourism means making as little environmental impact as possible and helping to sustain the indigenous populace thereby encouraging, the preservation of wild life and habitats when visiting a place. This is responsible form of tourism and tourism development, which encourages going back to natural products in every aspects of life. It is also the key to sustainable ecological development. -

List of Participants COMPLETE LIST of ALL QUALIFIED PARTICIPANTS with THEIR PROJECT NAMES

2008 landscape competition | List of Participants COMPLETE LIST OF ALL QUALIFIED PARTICIPANTS WITH THEIR PROJECT NAMES B.K.P.S. College of Architecture, Pune Bharati Vidyapeeth College of Architec- Guru Nanak Dev University, Amritsar 1. SHANIWAR WADA, PUNE ture, Pune 39. CENTRAL BUSINESS DISTRICT, NEW AMRITSAR Ajay Mane Ashish Batra, Karan Ganeriwala 21. RIVERFRONT DEVELOPMENT AT VITHALWADA, PUNE Faquih Museeb Talha, Pokale Parag Shriram 2. KASTURCHAND PARK, NAGPUR IIT, Rorkee Atreyee Ghosh 22. SEASONS - A GATHERING PLACE 40. COMMUNITY RECREATIONAL CENTRE, MUNDRA SEZ Kunal Deepchand Rathi, Prachi Satish Deshpande Abhijeet Sharma, Gaurav Mangla, Hrishi Raj Agarwalla 3. RIVERFRONT DEVELOPMENT FOR VITHALWADI, PUNE Neha Sanjeev Unawane 24. CULTURAL PORT OF COCHIN, TIDES OF CHANGE Jadhavpur University, Kolkata Parikh Ankit Anil, Neha Chavan 4. REVIVED IDENTITY 41. MAIDAN, KOLKATA Pradnya Rajan Nesarikar, Smita Yatish Prabhune, Roshmi Sen Sarang Sanjay Patwardhan Chitkara School of Architecture and Planning, Patiala Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi 5. PATALESHWAR CAVE COMPLEX 25. REVIIVING, NEHRU PLACE 42. COMMUNITY CENTRE, NEW FRIENDS COLONY Sneha Jagdish Thakur Hina Sahi, Kavita, Himanshu Suri Apurva Anand, Mansha Samreen Bharati Vidyapeeth College of Architec- College of Engineering, 43. NEHRU PLACE, LANDSCAPE Arshad Nafees, Kajoli Kerketta ture, Navi Mumbai Thiruvanathapuram 6. AMBE GHOSALE LAKE 26. BRIDGING THE HORIZON 44. SCAPING THE PRECINCT, JAMA MASJID Abhineet P. Ghag, Durgesh Tatkar, Vibhavari Patil Roshan Alexandar, Hetal J. Patel Iqtedar Alam, Ahmad Faraz Ansari 7. REVITALISING WELLINGTON CIRCLE 45. SARAI JULLENA PARK Amit Yadav, Suraj V. Majithia, Taher Rangwala CSIIT, Secundrabad 27. GATED COMMUNITY Kumar Abhishek, Md. Waseem Reza 8. GOLMAIDAN Koganti Ujwala 46. 127 ACRES NEAR NEHRU PLACE Asim Sadiq - Wadkar, Nilesh Bhojwani, Akshansh Md. -

Government of India Ministry of Jal Shakti, Department of Water Resources, River Development & Ganga Rejuvenation Lok Sabha Unstarred Question No

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF JAL SHAKTI, DEPARTMENT OF WATER RESOURCES, RIVER DEVELOPMENT & GANGA REJUVENATION LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO. †919 ANSWERED ON 27.06.2019 OLDER DAMS †919. SHRI HARISH DWIVEDI Will the Minister of JAL SHAKTI be pleased to state: (a) the number and names of dams older than ten years across the country, State-wise; (b) whether the Government has conducted any study regarding safety of dams; and (c) if so, the outcome thereof? ANSWER THE MINISTER OF STATE FOR JAL SHAKTI & SOCIAL JUSTICE AND EMPOWERMENT (SHRI RATTAN LAL KATARIA) (a) As per the data related to large dams maintained by Central Water Commission (CWC), there are 4968 large dams in the country which are older than 10 years. The State-wise list of such dams is enclosed as Annexure-I. (b) to (c) Safety of dams rests primarily with dam owners which are generally State Governments, Central and State power generating PSUs, municipalities and private companies etc. In order to supplement the efforts of the State Governments, Ministry of Jal Shakti, Department of Water Resources, River Development and Ganga Rejuvenation (DoWR,RD&GR) provides technical and financial assistance through various schemes and programmes such as Dam Rehabilitation and Improvement Programme (DRIP). DRIP, a World Bank funded Project was started in April 2012 and is scheduled to be completed in June, 2020. The project has rehabilitation provision for 223 dams located in seven States, namely Jharkhand, Karnataka, Kerala, Madhya Pradesh, Orissa, Tamil Nadu and Uttarakhand. The objectives of DRIP are : (i) Rehabilitation and Improvement of dams and associated appurtenances (ii) Dam Safety Institutional Strengthening (iii) Project Management Further, Government of India constituted a National Committee on Dam Safety (NCDS) in 1987 under the chairmanship of Chairman, CWC and representatives from State Governments with the objective to oversee dam safety activities in the country and suggest improvements to bring dam safety practices in line with the latest state-of-art consistent with Indian conditions. -

6. Water Quality ------61 6.1 Surface Water Quality Observations ------61 6.2 Ground Water Quality Observations ------62 7

Version 2.0 Krishna Basin Preface Optimal management of water resources is the necessity of time in the wake of development and growing need of population of India. The National Water Policy of India (2002) recognizes that development and management of water resources need to be governed by national perspectives in order to develop and conserve the scarce water resources in an integrated and environmentally sound basis. The policy emphasizes the need for effective management of water resources by intensifying research efforts in use of remote sensing technology and developing an information system. In this reference a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) was signed on December 3, 2008 between the Central Water Commission (CWC) and National Remote Sensing Centre (NRSC), Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) to execute the project “Generation of Database and Implementation of Web enabled Water resources Information System in the Country” short named as India-WRIS WebGIS. India-WRIS WebGIS has been developed and is in public domain since December 2010 (www.india- wris.nrsc.gov.in). It provides a ‘Single Window solution’ for all water resources data and information in a standardized national GIS framework and allow users to search, access, visualize, understand and analyze comprehensive and contextual water resources data and information for planning, development and Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM). Basin is recognized as the ideal and practical unit of water resources management because it allows the holistic understanding of upstream-downstream hydrological interactions and solutions for management for all competing sectors of water demand. The practice of basin planning has developed due to the changing demands on river systems and the changing conditions of rivers by human interventions. -

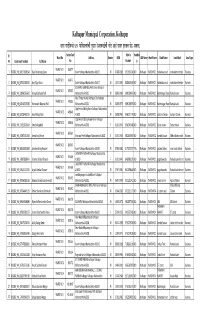

Street Vendor List Having Double Ration Card

Kolhapur Municipal Corporation, Kolhapur ºÉnù®ú ªÉÉnùÒ¨ÉvªÉä 492 ¡äò®Ò´ÉɱªÉÉÆSÉÒ nÖù¤ÉÉ®ú ®äú¶ÉxÉEòÉbÇ÷SÉÒ xÉÉånù +ɽäþ ªÉÉ´É®ú ½þ®úEòiÉ PÉä>ð ¶ÉEòiÉÉ. Sr. Ration Card Mobile Handica Ward No Address Gender DOB ULB Name Ward Name Road Name Land Mark Area Type no Enrollment Number Full Name No Number p WARD NO 1 454477 1 802887_HK_969171005548 Vijay Pandurang Gurav Karvir Kolhapur Maharashtra 416012 M 02-08-1962 9923913545 NO Kolhapur WARD NO 1 mahadava road mahalaxme temple Business WARD NO 1 454477 2 802887_HK_847532180392 Ajay Vijay Gurav Karvir Kolhapur Maharashtra 416012 M 14-11-1991 8605626464 NO Kolhapur WARD NO 1 mahadava road mahalaxme temple Business KOLHAPUR SAW MIL JAVAL Karvir Kolhapur WARD NO 1 473033 3 802887_HK_328960563610 Vinayak Baburao Patil Maharashtra 416012 M 08-06-1984 9890189976 NO Kolhapur WARD NO 1 Radhanagari Road Rankala Lake Business Near Timber market Kolhapur City Kolhapur WARD NO 1 473033 4 802887_HK_642400535583 Vishwanath Baburao Patil Maharashtra 416012 M 23-09-1979 9890189976 NO Kolhapur WARD NO 1 Radhanagari Road Rankala Lake Business Opp Perina Coldrig Karvir Kolhapur Maharashtra WARD NO 2 485948 5 802887_HK_875284463145 Amol Bhikaji Mali 416002 M 26-08-1991 9960717197 NO Kolhapur WARD NO 2 dashara Chowk dashara Chowk Business Opp Perina Coldrig House Karvir Kolhapur WARD NO 2 485948 6 802887_HK_731929629654 Uma Bhikaji Mali Maharashtra 416002 F 01-01-1947 9960745488 NO Kolhapur WARD NO 2 Dasra chowk Dasra chowk Business WARD NO 2 845760 7 802887_HK_590875311334 Amina Siraj Nurani Shaniwar Peth Kolhapur -

Shri Mahalaxmi Yatri Niwas Louge

+91-9370593007 Shri Mahalaxmi Yatri Niwas Louge https://www.indiamart.com/shri-mahalaxmi-yatriniwas/ Right from its inception in the year 2001,Shri Mahalaxmi Yatri Niwas strives to cater the needs of the Customers. It is the hard work and dedication of these 13 long years that speaks for our success. And thus we’re proud to call ourselves ... About Us Right from its inception in the year 2001,Shri Mahalaxmi Yatri Niwas strives to cater the needs of the Customers. It is the hard work and dedication of these 13 long years that speaks for our success. And thus we’re proud to call ourselves one of the leading names in the hospitality industry of Kolhapur. It feels great when the customers associated with us proudly call Shri Mahalaxmi Yatri Niwas as their second home in Kolhapur. We’re not just a Hotel or a Lodging. As in our name Shri Mahalaxmi Yatri Niwas, niwas means a home. And its our constant try to make our customers feel at home with the services we provide. We take care of our customers as if they’re at their homes. For more information, please visit https://www.indiamart.com/shri-mahalaxmi-yatriniwas/aboutus.html OTHER SERVICES P r o d u c t s & S e r v i c e s Mahalaxmi Temple Visit Rankala Lake Visit Services Service Shalini Palace Visit Services Panhala Fort Visit Services P r o OTHER SERVICES: d u c t s & S e r v i c e s Jyotiba Temple Visit Services New Palace Museum Visit Services Kaneri Math Museum Visit Narsoba Wadi Visit Services Services F a c t s h e e t Nature of Business :Service Provider CONTACT US Shri Mahalaxmi Yatri Niwas Louge Contact Person: Akshay Mahadwar Road, Mahalaxmi Temple, Kolhapur - 416012, Maharashtra, India +91-9370593007 https://www.indiamart.com/shri-mahalaxmi-yatriniwas/. -

Performance Evaluation of Deweeding Operations Implemented for Conservation of Rankala Lake, Kolhapur, India

EUROPEAN ACADEMIC RESEARCH Vol. II, Issue 11/ February 2015 Impact Factor: 3.1 (UIF) ISSN 2286-4822 DRJI Value: 5.9 (B+) www.euacademic.org Performance Evaluation of Deweeding Operations Implemented For Conservation of Rankala Lake, Kolhapur, India ABHIJEET S. GHONE SUNIL K. SINGAL Alternate Hydro Energy Centre, IIT Roorkee Uttarakhand, India Abstract Rankala Lake is situated in the heart of Kolhapur city of Maharashtra. The lake was earlier used for providing drinking water to Kolhapur city but now confined to irrigational and recreational use. Presently, lake serves as a popular picnic spot for the tourists and local residents. Being the location of this lake in centre of the city, there are many sewage terminals pouring sewages in the lake water and therefore heavily polluting the lake which leads to the formation of aquatic weeds in the lake. Lake is turning green since 2011 because of the presence of blue green algae. Since 1994 water hyacinth is been growing into the Rankala Lake at an alarming rate. Deweeding operations are implemented on Rankala Lake for its conservation since 1996 but lake has not become free of it till today. So there is a need to evaluate the performance of these deweeding operations to extract the failures and achievements of these measures so that it can be useful for future lake conservation implementation measures. Thus performance evaluated of this deweeding measure is given here in terms of the failures and achievements of it and some additional measures are also suggested for effective implementation of this measure in future. Based on this status of works and present status of the lake some temporary and permanent remedies for control of water hyacinth are suggested. -

Holy City Development Plan a Presentation to Shri Ashokrao Chavan Honourable Chief Minister, Maharashtra

KOLHAPUR: Holy City Development Plan A Presentation to Shri Ashokrao Chavan Honourable Chief Minister, Maharashtra By Kolhapur Municipal Corporation Fortress Structure of the Presentation A About Kolhapur B Kolhapur as a Tourism Destination C Project Outlay and Details D Financial & Implementation Plan Fortress Kolhapur : Location Overview Distances Mumbai : 390 Pune : 233 Bangalore : 614 Belgaum : 105 Goa : 237 Hyderabad : 551 Tirupati :900 Nashik : 435 Aurangabad : 475 Population 35 Lacs Tourists 40 lacs pa Strategically Located on the CorridorsFortress of NH 4 connecting Mumbai, Pune and Bangalore Kolhapur - one of the important economic regions of Maharashtra Strong Historic & Cultural Heritage Most attractive tourism destination Well established Economic infrastructure One of the richest agricultural belt of the country One of the higgpphest per capita income of the countr y One of the highest literate City Æ 90% Strong Education and Health Infrastructure District Population 35.25 Lacs Æ 30% Urban Fortress Kolhapur City – A Brief Profile City Area - 66 sq.kms Population – 5 Lakhs plus Literacy : >90% Economic Drivers Manufacturing, Tourism, Agriculture and Services Central Business Districts Mahadwar Rd, Laxmiopuri, Sahupuri & Rajarampuri Prime Residential Area Tarabai Park, Ruikar Colony, Nagala Park Rajaram Puri & Takala Connectivity Well connected by Rail, Road and Air Fortress Socio- Economic Infrastructure in Kolhapur Important Education destinations in Maharashtra due to • Presence of Shivaji University EDUCATION • District -

Existing Situation at Rankala Lake

Existing Situation at Rankala Lake Part of the Lake is infested with Water Hyacinth and polluted affecting the aquatic life as well as creatingFortress mosquito menace Proposed Integrated Plan for Rankala Lake. A Proposed State‐of‐Art Museum. E E B Proposed convergence space. E C Proposed artist village. D Proposed cultural complex ‐ food plaza. E Proposed Theme gardens. F Cleaning of the Lake / Rejuvenation. E E A D B C Fortress Proposed Cultural Center at Rankala Lake • Perfo rming Spaces • Multi-arts complex • Museum of Fine Arts • A Library • Indoor and outdoor auditoria Fortress Estimated Cost – 43 Cr. Proposed Museum of wrestling events in Kolhapur region KASBAG MAIDAN Proposed location for Gallery of wrestling history‐events. Fortress Estimated Cost – 5 Cr. Outer Circle Proposal: Koteshwar Mandir & Kotitirth Development Existing Status • Over 115.5 lc annual viitisitors • Garden with pathway overlooking the sacred lake • Good Seating arrangement • Beautiful Lake view • SiSwami SthSamarth MdiMandir Key Issues • Apppproach roads are not well maintained • No public utility facilities • No planned parking area • Grossly inadequate infrastructure Fortress Proposed Holistic Plan for Kotithirth Lake I Issues: • Approach roads are not well maintained I • No public utility facilities • No planned parking area I • Grossly inadequate infrastructure J F D I H G C E A B Proposed Activities – E Restaurant- organic food A Fast food F Meditation hall- B Shops- G Open air amphitheater- C Museum H Laser show Musical fountain- D Yoga hall / center I FortressGhat development Exhibition hall J Mythological wall paintings Estimated Cost – 13 Cr. Beautification of City Entry Points & Chowks Mappg showing Locations of Entr y Points of under consideration for Beautification Fortress Estimated Cost – 7 Cr.