The Heart of Rock and Soul by Dave Marsh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

The Rolling Stones and Performance of Authenticity

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Art & Visual Studies Art & Visual Studies 2017 FROM BLUES TO THE NY DOLLS: THE ROLLING STONES AND PERFORMANCE OF AUTHENTICITY Mariia Spirina University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2017.135 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Spirina, Mariia, "FROM BLUES TO THE NY DOLLS: THE ROLLING STONES AND PERFORMANCE OF AUTHENTICITY" (2017). Theses and Dissertations--Art & Visual Studies. 13. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/art_etds/13 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Art & Visual Studies at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Art & Visual Studies by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

3 Monday Midnights by Jamal Gerald PART 1

3 Monday Midnights by Jamal Gerald Mojuba Esu Modupe Open the doors, let's have some fun. I want to be known as troublesome. Ase Ase Ase. PART 1 Elvis, known as the King of Rock ‘n’ Roll. It’s time for a new story to be told. Banish away his catalogue and show the world a new dialogue. Burn his legacy and create a new destiny. Let a Queen astonish and let the King be demolished. It's Monday at midnight. I'm looking out the window like I'm waiting for a message from God, but I’m only waiting for my takeaway. It’ll be here in an hour. I’m thinking of God’s opposition, Lucifer. First off, what a beautiful name. I’ve always been fascinated by him. Yes, he’s evil. But there are some traits I find admirable. I love his rebellious nature. And I do love me a problematic fave. My subconscious leads me to the crossroads, where I sit and meditate with a blue waxing crescent smiling: the incense flickers and the smoke twirls. My spirit rises. But my meditation has been electrocuted by a white man singing about his white guilt. Eurgh. His liquorice tears are staining his charity shop clothing. Oh, what do you know? It's Elvis, the former King of Rock ‘n’ Roll. And yes, I said ‘former’. Elvis doesn't look like Elvis Presley. Natural blonde hair and eyebrows. No trace of black shoe polish in use. He has no care for being clean-shaven, looks similar to a caveman. -

Mood Music Programs

MOOD MUSIC PROGRAMS MOOD: 2 Pop Adult Contemporary Hot FM ‡ Current Adult Contemporary Hits Hot Adult Contemporary Hits Sample Artists: Andy Grammer, Taylor Swift, Echosmith, Ed Sample Artists: Selena Gomez, Maroon 5, Leona Lewis, Sheeran, Hozier, Colbie Caillat, Sam Hunt, Kelly Clarkson, X George Ezra, Vance Joy, Jason Derulo, Train, Phillip Phillips, Ambassadors, KT Tunstall Daniel Powter, Andrew McMahon in the Wilderness Metro ‡ Be-Tween Chic Metropolitan Blend Kid-friendly, Modern Pop Hits Sample Artists: Roxy Music, Goldfrapp, Charlotte Gainsbourg, Sample Artists: Zendaya, Justin Bieber, Bella Thorne, Cody Hercules & Love Affair, Grace Jones, Carla Bruni, Flight Simpson, Shane Harper, Austin Mahone, One Direction, Facilities, Chromatics, Saint Etienne, Roisin Murphy Bridgit Mendler, Carrie Underwood, China Anne McClain Pop Style Cashmere ‡ Youthful Pop Hits Warm cosmopolitan vocals Sample Artists: Taylor Swift, Justin Bieber, Kelly Clarkson, Sample Artists: The Bird and The Bee, Priscilla Ahn, Jamie Matt Wertz, Katy Perry, Carrie Underwood, Selena Gomez, Woon, Coldplay, Kaskade Phillip Phillips, Andy Grammer, Carly Rae Jepsen Divas Reflections ‡ Dynamic female vocals Mature Pop and classic Jazz vocals Sample Artists: Beyonce, Chaka Khan, Jennifer Hudson, Tina Sample Artists: Ella Fitzgerald, Connie Evingson, Elivs Turner, Paloma Faith, Mary J. Blige, Donna Summer, En Vogue, Costello, Norah Jones, Kurt Elling, Aretha Franklin, Michael Emeli Sande, Etta James, Christina Aguilera Bublé, Mary J. Blige, Sting, Sachal Vasandani FM1 ‡ Shine -

Giving America Back the Blues

GIVING AMERICA BACK THE BLUES OVERVIEW ESSENTIAL QUESTION How did the early Rolling Stones help popularize the Blues? OVERVIEW The Rolling Stones ultimately made their mark as the nonconformist outlaws of Rock and Roll. But before they were bad boys, the Stones were missionaries of the Blues. The young Rolling Stones — Mick Jagger, Keith Richards, Brian Jones, Charlie Watts, and Bill Wyman — were white kids who hailed from working- and middle-class Britain and set out to play American music, primarily that of African Americans with roots in the South. In so doing, they helped bring this music to a new, largely white audience, both in Britain and the United States. The young men who formed the Rolling Stones emerged from the club scene fostered by British Blues pioneers Cyril Davies and Alexis Korner. These two men and their band, Blues Incorporated, helped popularize the American Blues, whose raw intensity resonated with a generation of Britons who had grown up in the shadow of war, death, the Blitz, postwar rationing, and the hardening of the Cold War standoff. Much of the Stones’ early work consisted of faithful covers of American Blues artists that Davies, Korner, and the Stones venerated: Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Slim Harpo, Jimmy Reed. The early Stones in particular helped make the Blues wildly popular among young Britons. As the Stones’ fame grew and they became part of the mid-1960s British “invasion” of America, they also reintroduced the Blues to American listeners, most notably young, white audiences with limited exposure to the music. But almost from day one, the Stones were more than a Blues cover band. -

Rock Around the Clock”: Rock ’N’ Roll, 1954–1959

CHAPTER EIGHT: “ROCK AROUND THE CLOCK”: ROCK ’N’ ROLL, 1954–1959 Chapter Outline I. Rock ’n’ Roll, 1954–1959 A. The advent of rock ’n’ roll during the mid-1950s brought about enormous changes in American popular music. B. Styles previously considered on the margins of mainstream popular music were infiltrating the center and eventually came to dominate it. C. R&B and country music recordings were no longer geared toward a specialized market. 1. Began to be heard on mainstream pop radio 2. Could be purchased nationwide in music stores that catered to the general public D. Misconceptions 1. It is important to not mythologize or endorse common misconceptions about the emergence of rock ’n’ roll. a) Rock ’n’ roll was not a new style of music or even any single style of music. CHAPTER EIGHT: “ROCK AROUND THE CLOCK”: ROCK ’N’ ROLL, 1954–1959 b) The era of rock ’n’ roll was not the first time music was written specifically to appeal to young people. c) Rock ’n’ roll was not the first American music to bring black and white pop styles into close interaction. d) “Rock ’n’ roll” was a designation that was introduced as a commercial and marketing term for the purpose of identifying a new target for music products. II. The Rise of Rhythm & Blues and the Teenage Market A. The target audience for rock ’n’ roll during the 1950s consisted of baby boomers, Americans born after World War II. 1. Relatively young target audience 2. An audience that shared some specific important characteristics of group cultural identity: a) Recovering from the trauma of World War II—return to normalcy b) Growing up in the relative economic stability and prosperity of the 1950s yet under the threat of atomic war between the United States and the USSR CHAPTER EIGHT: “ROCK AROUND THE CLOCK”: ROCK ’N’ ROLL, 1954–1959 c) The first generation to grow up with television—a new outlet for instantaneous nationwide distribution of music d) The Cold War with the Soviet Union was in full swing and fostered the anticommunist movement in the United States. -

I Saw Her Standing There (The Beatles)

I Saw Her Standing There (The Beatles) [Verse 1: Paul McCartney] And we held each other tight Well, she was just 17 And before too long I fell in love with her And you know what I mean And the way she looked [Chorus: Paul McCartney & John Lennon] Was way beyond compare Now, I'll never dance with another (Woo) When I saw her standing there [Chorus: Paul McCartney & John Lennon] So how could I dance with another (Ooh) [Guitar Solo: George Harrison] When I saw her standing there? [Bridge: Paul McCartney & John Lennon] [Verse 2: Paul McCartney] Well, my heart went "boom" Well, she looked at me When I crossed that room And I, I could see And I held her hand in mine That before too long I'd fall in love with her [Verse 4: Paul McCartney & John Lennon] Oh, we danced through the night [Chorus: Paul McCartney & John Lennon] And we held each other tight She wouldn't dance with another (Woo) And before too long When I saw her standing there I fell in love with her [Bridge: Paul McCartney & John Lennon] [Chorus: Paul McCartney & John Lennon] Well, my heart went "boom" Now I'll never dance with another (Woo) When I crossed that room Since I saw her standing there And I held her hand in mine [Outro: Paul McCartney & John Lennon] [Verse 3: Paul McCartney] Oh, since I saw her standing there Well, we danced through the night Yeah, well, since I saw her standing there 101 "I Saw Her Standing There" is the opening track on The Beatles’ 1963 debut album Please Please Me. -

Bandworks Song List **Please Circle All Songs You Would Like to Perform in the Next Session**

BandWorks Song List **Please circle all songs you would like to perform in the next session** After Midnight (Eric Clapton) Break on Through (Doors) Don’t Change Horses [In the Middle A Hard Day’s Night (Beatles) Breathe (Pink Floyd) of a Stream] (Tower of Power) Ain’t That Peculiar (Marvin Gaye) Brick House (Commodores) Don’t Let the Sun Catch You Cryin’ Ain’t Wastin’ Time No More (Allman Bros.) Brown-Eyed Girl (Van Morrison) (Ray Charles) Alison (Elvis Costello) Buddy Holly (Weezer) Don’t Lose Your Cool (Albert Collins) Alive (Pearl Jam) Burning Down the House (Talking Heads) Don’t Speak (No Doubt) All Along the Watchtower (Bob Dylan) Burn to Shine (Ben Harper) Don’t Talk About My Mama All Apologies (Nirvana) By the Way (Red Hot Chili Peppers) (Mem Shanon) All For You (Sister Hazel) Cabron (Red Hot Chili Peppers) Don’t Throw That Mojo on Me All My Love (Led Zeppelin) Caldonia (Bb King) (Wynona Judd) All You Need Is Love (Beatles) Caledonia Mission (The Band) Do Your Thing (Lyn Collins) All Your Love (Otis Rush) California (Lenny Kravitz) Down Payment Blues (AC/DC) Alone (Susan Tedeschi) Callin’ San Francisco (Tommy Castro) Dreams (Fleetwood Mac) American Girl (Tom Petty) Call Me the Breeze (Lynyrd Skynyrd) Dr. Feelgood (Aretha Franklin) American Idiot (Green Day) Can’t Find My Way Home (Blind Faith) Drive South (John Hiatt) And It Stoned Me (Van Morrison) Can’t Get Next to You (Al Green) Drops of Jupiter (Train) And She Was (Talking Heads) Canteloupe Island (Herbie Hancock) Elevation (U2) Angel (Jimi Hendrix) Caravan (Van Morrison) -

KEEP on PUSHING the Fight for Civil Rights and Black Empowerment in the Context of Rock ‘N’ Roll in Philadelphia

KEEP ON PUSHING The Fight for Civil Rights and Black Empowerment in the Context of Rock ‘n’ Roll in Philadelphia Lee Junkin Senior History Essay Spring 2016 African Americans in the southern United States, experiencing increased racial oppression through segregation and lynching, as well as seeking better economic opportunities, began moving north at an exponential rate starting after the Great Depression. Philadelphia was one of the northern cities that took in many of the migrants. The growth of the black population in Philadelphia increased the strain of racial tensions in the city. As historian Matthew Delmont points out in his book The Nicest Kids In Town, “from 1930-1960, the city’s black population grew by three hundred thousand, increasing from 11.4 percent of the city’s total population to 26.4 percent.”1 The growing racial diversity and developing culture of the city, along with the progression of the American Civil Rights Movement in the 1950’s and 60’s, established Philadelphia as a battleground for racial relations and social change. The movement of African Americans into northern cities began to change many aspects of American life, including popular music. This migration into urban areas, as well as increased access to electric instruments, caused a shift in black rhythm and blues musicians’ approaches to music. Music was played faster and with more energy. White musicians picked up on these musical changes and took black rock and crossed it with certain aspects of popular white music such as country-style lyrics and a cleaner sound. Music historians began to call this “rockabilly music”, a cross between rock ‘n’ roll and “hillbilly” country sounds. -

Chuck Berry: Father of Rock & Roll

Country Music Hall of Fame® and Museum • Words & Music • Grades 7-12 Chuck Berry: Father of Rock & Roll While many artists are rock pioneers, Chuck Berry is universally considered the first who put it all together: the country guitar licks, the rhythm and blues beat, and lyrics that spoke to a young generation. In just a few songs, he drew a musical blueprint for what the world would soon know as rock & roll. “He may be the single most important name in the history of rock,” critic Lillian Roxon wrote in her 1969 landmark Rock Encyclopedia. “If you tried to give rock & roll another name,” Beatle John Lennon once said, “you might call it Chuck Berry.” Born October 18, 1926, in St. Louis, Missouri, Berry grew up in a middle-class African American neighborhood, the fourth of six children. His father was a part-time preacher and his mother sang in the choir, so gospel was Berry’s earliest musical influence. The radio later introduced him to boogie-woogie, blues, swing, and “hillbilly” songs. After he wowed classmates with a vocal performance in high school, Berry was determined to have a music career. Detoured by a three-year prison term for a teenage robbery spree, Berry By year’s end, “Maybellene” had sold a million copies, and Berry saw got back on track and became a popular performer in St. Louis clubs he had tapped into an emerging market: white teenagers with new singing other artists’ songs. Soon he began writing his own, at first by buying power who were searching for music they could call their own. -

“What'd I Say” (Parts 1 and 2)--Ray Charles (1959) Added to the National Registry: 2002 Essay by Michael Lydon (Guest Post)*

“What'd I Say” (Parts 1 and 2)--Ray Charles (1959) Added to the National Registry: 2002 Essay by Michael Lydon (guest post)* Original label Here’s a seldom noted but significant fact about the long and distinguished career of Ray Charles: unlike his contemporaries--Chuck Berry, Fats Domino, Little Richard, and Bo Diddley--who all became rock ‘n’ roll stars by making their first records smash hits, he, Brother Ray, the Genius, the High Priest, the biggest star of them all, took the whole decade of the 1950s to emerge, step by steady step, out from the shadows of obscurity into the bright lights of international fame. In early 1950, Ray touched the black “race records” charts with “Baby Let Me Hold Your Hand”; five years later, he crossed over into the white charts with “I Got a Woman” (also a hit for Elvis Presley!) and “Hallelujah I Love Her So.” Next came “Movin’ On,” Ray’s first foray into country music, then “Soul Brothers,” some jazz with vibraphonist Milt Jackson. Having systematically covered the major branches of contemporary popular music, Ray must have thought from time to time, “What more can I do, what do I have left to conquer?” Thoughts like that may well have been crossing Ray’s mind in January 1959 as his touring caravan rolled east from Pittsburgh. At a dance in Brownsville, an industrial town, Ray realized he had run out of things to play that fit the excited mood of the dancers leaping and spinning before the stage. “So I said to the guys,” Ray recalled years later, “’Look, I don’t know where I’m going, so y’all follow me.’ Then I turned to the Raelettes and said, ‘Whatever I say, just repeat after me.’” Ray started a low, bouncy riff on electric piano, the drummer clicked in on his big cymbal, the band fell into an up-tempo groove, and Ray started singing nonsense choruses: “See that gal with a diamond ring, she knows how to shake that thing.” The crowd loved it and, without knowing that a song was being made up on the spot, fell into the improvisatory feeling. -

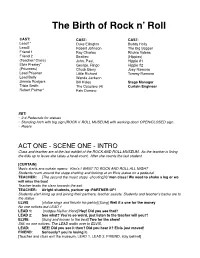

Rock Around the Clock Musical2

The Birth of Rock n’ Roll! ! ! CAST:! ! CAST:! CAST:! Lead1*! ! Duke Ellington Buddy Holly! Lead2! ! Robert Johnson! The Big Bopper! Friend 1! ! Ray Charles! Ritchie Valens! Friend 2! ! Beatles:! (Hippies)! (Teacher/ Class)! ! John, Paul, Hippie #1! Elvis Presley*! ! George, Ringo! Hippie #2! (Prisoners)! ! Chuck Berry! Joey Ramone! Lead Prisoner ! ! Little Richard! Tommy Ramone! Lead Belly! ! Wanda Jackson! ! Jimmie Rodgers! ! Bill Haley! Stage Manager! Trixie Smith! ! The Coasters (4)! Curtain Engineer Robert Palmer*! ! Fats Domino ! ! ! ! ! SET:! • 2-4 Pedestals for statues! • Standing Arch with big sign [ROCK n’ ROLL MUSEUM] with working door/ OPEN/CLOSED sign.! !• Risers! ! ! ACT ONE - SCENE ONE - INTRO! Class and teacher are at the last exhibit of the ROCK AND ROLL MUSEUM. As the teacher is lining !the kids up to leave she takes a head count. After she counts the last student! [CURTAIN]! Music starts and curtain opens: Kiss’s I WANT TO ROCK AND ROLL ALL NIGHT! Students roam around the stage chatting and looking at an Elvis statue on a pedestal. ! TEACHER: ! [The second the music stops -shouting] C’mon class! We need to shake a leg or we will miss the bus!! Teacher leads the class towards the exit.! TEACHER: !Alright students, partner up -PARTNER-UP!! Students start lining up and joining their partners, teacher assists. Students and teacher’s backs are to the statue! ELVIS !! [statue sings and thrusts his pelvis] [Sung] Well it’s one for the money! No one notices but LEAD 1! LEAD 1:! [nudges his/her friend] Hey! Did you see that?! LEAD 2: ! See what? You’re so weird, just listen to the teacher will you?!! ELVIS: ! [Sung and moves to the beat] Two for the show!! Still, no one notices.