Party Politics in Ireland In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Creation Dates: 13 February 1987

Reference Code: 2017/10/73 Creation Dates: 13 February 1987 Extent and medium: 4 pages Creator(s): Department of the Taoiseach Accession Conditions: Open Copyright: National Archives, Ireland. May only be reproduced with the written permission of the Director of the National Archives. .. ' 17, GROSVENOR PLACE, AM2~0 NA~ANN, L0NDAI SW1X 7HR Telephone: 01-235 2171 TELEX: 916104 Time _LONDON IRISH EMBASSY,- . ..... CONFIDENTIAL By Special Bag 13 February 1987 A Conversation with Ron Aitken, Political Adviser to Martin Smyth MP 11. \., . Y'7 Dear Assistant Secretary Aitken receives an allowance from Martin Smyth and the OUP to be their only adviser at Westminster. He is something of a maverick having been first active as a SPUC organiser in Ireland during the anti-abortion campaign. His principal loyalty is to Smyth who spends 2 or 3 days a week in Britain, giving speeches to low key student and minority groups. The major theme on these occasions reflects the line from Frank Millar in Belfast: 'When is the British Government going to do something for the reasonable OUP to stop it losing out to the nasty DUP?' No doubt this appeal is modeled on what Unionists consider to have been a successful tactic employed by the SDLP in relation to Sinn Fein. Aitken illustrates the danger by saying that Roy Beggs in East Antrim and Cecil Walker in North Belfast could loose to DUP challenges if the Election is much delayed; furthermore Kilfeddar could be vulnerable in North Down. If this were to happen the spectre of Brian Faulkner would haunt the party and undermine those in favour of power-sharing. -

Five Days in Labour Party History by Brendan

SNAPSHOTS: FIVE DAYS IN LABOUR PARTY HISTORY Essays originally published in The Irish Times, 1978 By Brendan Halligan 1 SNAPSHOTS: FIVE DAYS OF LABOUR PARTY HISTORY By Brendan Halligan Essays originally published in The Irish Times, 1978 1. The Triumph of the Green Flag: Friday, 1 November 1918 2. The Day Labour almost came to Power: Tuesday, 16 August 1927 3. Why Labout Put DeValera in Power: 9 March 1932 4. Giving the Kiss of Life to Fine Gael: Wednesday, 18 February 1948 5. The Day the Party Died: Sunday, 13th December 1970 2 No. 1 The Triumph of the Green Flag: Friday, 1 November 1918 William O’Brien Fifteen hundred delegates jammed the Mansion House. It was a congress unprecedented in the history of the Labour Movement in Ireland. Or, in the mind of one Labour leader, in the history of the Labour movement in any country in Europe. The euphoria was forgivable. The Special Conference of the Irish Labour Party and Trade Union Congress (to give it its full name) was truly impressive, both in terms of its size and the vehemence with which it opposed the conscription a British government was about to impose on Ireland. But it was nothing compared to what happened four days later. Responding to the resolution passed by the Conference, Irish workers brought the economic life of the country to a standstill. It was the first General Strike in Ireland. Its success was total, except for Belfast. Nothing moved. Factories and shops were closed. No newspapers were printed. Even the pubs were shut. -

From Deference to Defiance: Popular Unionism and the Decline of Elite Accommodation in Northern Ireland

From Deference to Defiance: Popular Unionism and the Decline of Elite Accommodation in Northern Ireland Introduction On 29 November, 2003, The Ulster Unionist Party (UUP), the party that had governed Northern Ireland from Partition in 1921 to the imposition of Direct Rule by Ted Heath in 1972, lost its primary position as the leading Unionist party in the N.I. Assembly to the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) of Reverend Ian Paisley. On 5 May, 2005, the electoral revolution was completed when the DUP trounced the UUP in the Westminster elections, netting twice the UUP's popular vote, ousting David Trimble and reducing the UUP to just one Westminster seat. In March, 2005, the Orange Order, which had helped to found the UUP exactly a century before, cut its links to this ailing party. What explains this political earthquake? The press and most Northern Ireland watchers place a large amount of stress on short-term policy shifts and events. The failure of the IRA to show 'final acts' of decommissioning of weapons is fingered as the main stumbling block which prevented a re-establishment of the Northern Ireland Assembly and, with it, the credibility of David Trimble and his pro-Agreement wing of the UUP. This was accompanied by a series of incidents which demonstrated that the IRA, while it my have given up on the ‘armed struggle’ against the security forces, was still involved in intelligence gathering, the violent suppression of its opponents and a range of sophisticated criminal activities culminating in the robbery of £26 million from the Northern Bank in Belfast in December 2004. -

The Political Role of Northern Irish Protestant Religious Denominations

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Supervised Undergraduate Student Research Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects and Creative Work 2-1991 The Political Role of Northern Irish Protestant Religious Denominations Henry D. Fincher Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj Recommended Citation Fincher, Henry D., "The Political Role of Northern Irish Protestant Religious Denominations" (1991). Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/68 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Supervised Undergraduate Student Research and Creative Work at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. - - - - - THE POtJ'TICAIJ I~OI~E OF NOR'TI-IERN IRISH - PROTESrrANrr REI~IGIOUS DENOMINATIONS - COLLEGE SCIIOLAR5,/TENNESSEE SCIIOLARS PROJECT - HENRY D. FINCHER ' - - FEnRlJARY IN, 1991 - - - .. - .. .. - Acknowledgements The completion of this project would have been impossible without assistance from many different individuals in the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Republic of Ireland. I appreciate the gifts of interviews from the MP's for South Belfast and South Wirral, respectively the Reverend Martin Smyth and the Honorable Barry Porter. Li kewi se, these in terv iews would have been impossible without the assistance of the Rt. Hon. Merlyn Rees MP PC, who arranged these two insightful contacts for me. In Belfast my research was aided enormously through the efforts of Mr. Robert Bell at the Linen Hall Library, as well as by the helpful and ever-cheerful librarians at the University of Ulster at Jordanstown. -

Thirteenth Dáil

THIRTEENTH DÁIL Thirteenth Dáil (18.2.1948 - 7.5.1951) Fifth Government (18.2.1948 - 13.6.1951) Name: Post held: John A. Costello Taoiseach Minister for Health (from: 12.4.1951) William Norton Tánaiste & Minister for Social Welfare Minister for Local Government (3.5.49 to 11.5.49) Sean Mac Bride Minister for External Affairs Patrick McGilligan Minister for Finance Daniel Morrissey Minister for Industry & Commerce (to: 7.3.1951) Minister for Justice (from: 7.3.1951) Timothy J. Murphy Minister for Local Government (died : 29.4.49) Noel C. Browne Minister for Health (to: 11.4.1951 - resigned) (see J. A. Costello above) James M. Dillon Minister for Agriculture Richard Mulcahy Minister for Education Sean MacEoin Minister for Justice (to: 7.3.1951) Minister for Defence (from: 7.3.1951) Thomas F. O'Higgins Minister for Defence (to: 7.3.1951) Minister for Industry & Commerce (from: 7.3.1951) James Everett Minister for Posts & Telegraphs Joseph Blowick Minister for Lands Michael Keyes Minister for Local Government (from: 11.5.1949) - 1 - THIRTEENTH DÁIL (Thirteenth Dáil (18.1.1948 - 7.5.1951) / Fifth Government (18.1.1948 - 13.6.1951) condt. Notes: (1) Following the dissolution of a Dáil, the Government remain in office, even if it loses the General Election, until the new Dáil meets and nominates a new Government. (2) Inter-party Government comprising of Fine Gael, Labour, Clann na Talmhúain & Clann na Pobhlachta. (3) William Norton acted as Minister for Local Government in the period between Mr. Murphy's death and Mr. Keyes' appointment. (4) Ministers are listed in order of seniority. -

The Protectionist Campaign by the Irish Barley Growers, 1919–34*

The protectionist campaign by the Irish Barley growers, 1919–34* by Raymond Ryan Abstract The post-First World War disruption to agricultural supply and demand heralded a long-term decline in the Irish barley industry. After initial attempts at collective bargaining and negotiations with brewers, the majority of Irish barley growers sought government assistance for their sector, through tariffs and guaranteed prices. However, given the hostility of the Cumann na nGaedheal administration and of the Irish Farmers’ Union to Protectionism, the barley growers’ persistent campaign had the consequence of increasing support for Fianna Fáil, who introduced protection for the barley sector in 1932. The years immediately following the First World War witnessed significant turbulence in the demand, supply and price of agricultural produce throughout western Europe. The Irish barley industry was no exception and the post-war disruption heralded a protracted decline in both the Irish barley acreage and in prices. Barley growers responded with a protracted campaign to seek government assistance in the form of guaranteed prices for their sector and tariffs on imported produce.1 Their efforts have received some attention within the historiography. Dennison and MacDonagh have studied the relationship between Guinness and the barley growers during the 1920s and more briefly during the 1930s as part of their history of the Guinness Brewery, while Daly has briefly considered their demands in the context of the general campaign for protectionist economic policies.2 This article will expand the existing historiography by describing the anatomy of the barley growers’ campaign in detail, showing the way it affected the representative farming organizations of the period, and how the demands for the barley sector eased the acceptance of farmers for protectionist economic policies. -

The Orange Order in Northern Ireland: Has Political Isolation, Sectarianism, Secularism, Or Declining Social Capital Proved the Biggest Challenge?

The Orange Order in Northern Ireland: Has political isolation, sectarianism, secularism, or declining social capital proved the biggest challenge? Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of Liverpool for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy by Andrew McCaldon August 2018 Department of Politics University of Liverpool Liverpool L69 3BX The Orange Order in Northern Ireland Contents Dedication 003 Acknowledgements 004 Abstract 005 List of Abbreviations 006 List of Tables 007 Introduction 008 Chapter One The Orange Order in Northern Ireland: The State of Play 037 Chapter Two From pre– to post–Agreement Northern Ireland: 070 Political isolation and the Grand Orange Lodge Chapter Three Intolerance in a tolerant society? 106 Parading, sectarianism, and declining middle–class respectability Chapter Four An Order Re–routed: 135 Interface Orangeism in Drumcree and Ardoyne Chapter Five ‘The Biggest Threat’? The impact of secularism 167 Chapter Six Parading Alone: The decline of social capital in 195 Northern Ireland and its impacts on the Orange Order Conclusion 228 Bibliography 239 Appendix I Interview Questions 266 Andrew McCaldon Page 2 of 267 The Orange Order in Northern Ireland For my mother who, by the second Twelfth of July parade, started to enjoy them and my uncle, Ian Buxton (1968–2018) who never got to see it finished Andrew McCaldon Page 3 of 267 The Orange Order in Northern Ireland Acknowledgements To Professor Jon Tonge, I offer my sincere thanks for having withstood the mental anguish of supervising both my undergraduate and postgraduate research at the University of Liverpool. His advice has been beyond invaluable and he is the model of patience, whose professionalism, knowledge–base, and subject enthusiasm never cease to amaze me. -

Chapter Two the Timing of the Election and Cumann Na Ngaedheal's

Was defeat inevitable for Cumann na nGaedheal in the 1932 general election? By John Hanamy Thesis completed under the supervision of Dr Bernadette Whelan in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of M.A. in History at the University of Limerick. 2013 Table of contents Page Abstract ……………………………………………………………………. ii Acknowledgements ………………………………………………………. iii List of tables ………………………………………………………………. iv List of appendices …………………………………………………………. v Chapter One Introduction …………………………………………………………………. 1 Chapter Two The timing of the election and Cumann na nGaedheal’s election strategy …. 10 Chapter Three Election policies: Fianna Fáil, The Labour Party, The Farmers’ Party Independents and others ……………………………………………………. 38 Chapter Four Newspaper coverage of the final week of the election campaign, 8-16 February 1932 ………………………………………………………… 68 Chapter Five Election results: An analysis of the ten seats lost by Cumann na nGaedheal ……………………………………………………… 97 Chapter Six Conclusion ………………………………………………………………… 141 Appendices ……………………………………………………………….. 146 Bibliography ……………………………………………………………… 160 i Abstract Was defeat inevitable for Cumann na nGaedheal in the 1932 general election? By John Hanamy This thesis looks at the election that terminated the first government of the Irish Free State, and effectively the career of the party that formed that government. An analysis of the policies of Cumann na nGaedheal in 1932 and a comparison of those policies with those of the main opposition party Fianna Fáil will determine why the party lost power. An examination of the support base of the party and Cumann na nGaedheal’s loyalty to its supporters will demonstrate that the government party had little choice in the policies it offered to the voters in the election. The methodology chosen to carry out this analysis is a series of research issues relevant to the period under examination. -

Reimagining Ireland, Volume 48 : Visualizing Dublin

REIR imagining 48 imagining ire land ire land VOLUME 48 Justin Carville (ed.) Dublin has held an important place throughout Ireland’s cultural history. The shifting configurations of the city’s streetscapes have been marked VISUALIZING DUBLIN VISUALIZING by the ideological frameworks of imperialism, its architecture embedded within the cultural politics of the nation, and its monuments and sculptures VISUALIZING DUBLIN mobilized to envision the economic ambitions of the state. This book examines the relationship of Dublin to Ireland’s social history through the VISUAL CULTURE, MODERNITY AND THE city’s visual culture. Through specific case studies of Dublin’s streetscapes, REPRESENTATION OF URBAN SPACE architecture and sculpture and its depiction in literature, photography and cinema, the contributors discuss the significance of visual experiences and representations of the city to our understanding of Irish cultural life, both past and present. Justin Carville (ed.) Drawing together scholars from across the arts, humanities and social sciences, the collection addresses two emerging themes in Irish studies: the intersection of the city with cultural politics, and the role of the visual in projecting Irish cultural identity. The essays not only ask new questions of existing cultural histories but also identify previously unexplored visual representations of the city. The book’s interdisciplinary approach seeks to broaden established understandings of visual culture within Irish studies to incorporate not only visual artefacts, but also textual descriptions and ocular experiences that contribute to how we come to look at, see and experience both Dublin and Ireland. Justin Carville teaches Historical and Theoretical Studies in Photography and Visual Culture at the Institute of Art, Design and Technology, Dun Laoghaire. -

~R:O~~ Mr Thomas - B 1/7Fo? ·(8 Mr Kirk - B Mr Daniell - B

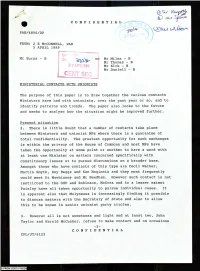

CON F I DEN T I PAB/4896/DP FROM: J E McCONNELL, PAB 5 APRIL 1989 Mr Burns - B c~ Mr Miles - B ~r:o~~ Mr Thomas - B 1/7fo? ·(8 Mr Kirk - B Mr Daniell - B MINISTERIAL CONTACTS WITH UNIONISTS The purpose of this paper is to draw together the various contacts Ministers have had with unionists, over the past year or so, and to identify patterns and trends. The paper also looks to the future and seeks to analyse how the situation might be improved further. Present situation 2. There.. is little doubt that a number of contacts take place between Ministers and unionist MPs where there is a guarantee of total confidentiality. The greatest opportunity for such exchanges is within the privacy of the House of Commons and most MPs have taken the opportunity at some point or another to have a word with at least one Minister on matters concerned specifically with constituency issues or to pursue discussions on a broader base. Amongst those who have contacts of this type are Cecil Walker, Martin Smyth, Roy Beggs and Ken Maginnis and they most frequently would meet Dr Mawhinney and Mr Needham. However such contact is not restricted to the OUP and Robinson, McCrea and to a lesser extent Paisley have all taken opportunity to pursue individual cases . It is apparent also that Molyneaux is increasingly finding it possible to discuss matters with the Secretary of State and also to allow this to be known in senior unionist party circles. 3. However all is not sweetness and light and at least two, John Taylor and Harold McCusker, refuse to make contact and on occasions -3- CON F I DEN T I A L CPL/JT/6123 CON F I DEN T I A L have been offensive. -

Air Transport Services in Northern Ireland

House of Commons Northern Ireland Affairs Committee Air Transport Services in Northern Ireland Eighth Report of Session 2004–05 Volume II Oral and written evidence Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 6 April 2005 HC 53 - II [Incorporating HC 1254-i, Session 2003-04] Published on 14 April 2005 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £18.50 The Northern Ireland Affairs Committee The Northern Ireland Affairs Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Northern Ireland Office (but excluding individual cases and advice given by the Crown Solicitor); and other matters within the responsibilities of the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland (but excluding the expenditure, administration and policy of the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions, Northern Ireland and the drafting of legislation by the Office of the Legislative Counsel). Current membership Mr Michael Mates, MP (Conservative, East Hampshire) (Chairman) Mr Adrian Bailey, MP (Labour / Co-operative, West Bromwich West) Mr Roy Beggs, MP (Ulster Unionist Party, East Antrim) Mr Gregory Campbell, MP (Democratic Unionist Party, East Londonderry) Mr Tony Clarke, MP (Labour, Northampton South) Mr Stephen Hepburn (Labour, Jarrow) Mr Iain Luke, MP (Labour, Dundee East ) Mr Eddie McGrady, MP (Socialist Democratic Labour Party, South Down) Mr Stephen Pound, MP (Labour, Ealing North) Rev Martin Smyth, MP (Ulster Unionist Party, Belfast South) Mr Hugo Swire, MP (Conservative, East Devon) Mark Tami, MP (Labour, Alyn & Deeside) Mr Bill Tynan, MP (Labour, Hamilton South) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. -

Ways of Dealing with Northern Ireland's Past: Interim Report - Victims and Survivors

House of Commons Northern Ireland Affairs Committee Ways of Dealing with Northern Ireland's Past: Interim Report - Victims and Survivors Tenth Report of Session 2004–05 Volume I HC 303-I House of Commons Northern Ireland Affairs Committee Ways of Dealing with Northern Ireland's Past: Interim Report - Victims and Survivors Tenth Report of Session 2004–05 Volume I Report, together with formal minutes Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 6 April 2005 HC 303-I Published on 14 April 2005 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 The Northern Ireland Affairs Committee The Northern Ireland Affairs Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Northern Ireland Office (but excluding individual cases and advice given by the Crown Solicitor); and other matters within the responsibilities of the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland (but excluding the expenditure, administration and policy of the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions, Northern Ireland and the drafting of legislation by the Office of the Legislative Counsel). Current membership Mr Michael Mates, MP (Conservative, East Hampshire) (Chairman) Mr Adrian Bailey, MP (Labour / Co-operative, West Bromwich West) Mr Roy Beggs, MP (Ulster Unionist Party, East Antrim) Mr Tony Clarke, MP (Labour, Northampton South) Mr Stephen Hepburn (Labour, Jarrow) Mr Iain Luke, MP (Labour, Dundee East ) Mr Eddie McGrady, MP (Socialist Democratic Labour Party, South Down) Mr Stephen Pound, MP (Labour, Ealing North) Mr Gregory Campbell, MP (Democratic Unionist Party, East Londonderry) Rev Martin Smyth, MP (Ulster Unionist Party, Belfast South) Mr Hugo Swire, MP (Conservative, East Devon) Mr Mark Tami, MP (Labour, Alyn & Deeside) Mr Bill Tynan, MP (Labour, Hamilton South) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152.