Chapter Two the Timing of the Election and Cumann Na Ngaedheal's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyrighted Material

Index Note: page numbers in italics denote illustrations or maps Abbey Theatre 175 sovereignty 390 Abbot, Charles 28 as Taoiseach 388–9 abdication crisis 292 and Trimble 379, 409, 414 Aberdeen, Earl of 90 Aiken, Frank abortion debate 404 ceasefire 268–9 Academical Institutions (Ireland) Act 52 foreign policy 318–19 Adams, Gerry and Lemass 313 assassination attempt 396 and Lynch 325 and Collins 425 and McGilligan 304–5 elected 392 neutrality 299 and Hume 387–8, 392, 402–3, 407 reunification 298 and Lynch 425 WWII 349 and Paisley 421 air raids, Belfast 348, 349–50 St Andrews Agreement 421 aircraft industry 347 on Trimble 418 Aldous, Richard 414 Adams, W.F. 82 Alexandra, Queen 174 Aer Lingus 288 Aliens Act 292 Afghan War 114 All for Ireland League 157 Agar-Robartes, T.G. 163 Allen, Kieran 308–9, 313 Agence GénéraleCOPYRIGHTED pour la Défense de la Alliance MATERIAL Party 370, 416 Liberté Religieuse 57 All-Ireland Committee 147, 148 Agricultural Credit Act 280 Allister, Jim 422 agricultural exports 316 Alter, Peter 57 agricultural growth 323 American Civil War 93, 97–8 Agriculture and Technical Instruction, American note affair 300 Dept of 147 American War of Independence 93 Ahern, Bertie 413 Amnesty Association 95, 104–5, 108–9 and Paisley 419–20 Andrews, John 349, 350–1 resignation 412–13, 415 Anglesey, Marquis of 34 separated from wife 424 Anglicanism 4, 65–6, 169 Index 513 Anglo-American war 93 Ashbourne Purchase Act 133, 150 Anglo-Irish Agreement (1938) 294, 295–6 Ashe, Thomas 203 Anglo-Irish Agreement (1985) Ashtown ambush 246 aftermath -

New Media, Free Expression, and the Offences Against the State Acts

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2020 New Media, Free Expression, and the Offences Against the State Acts Laura K. Donohue Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/2248 https://ssrn.com/abstract=3825722 Laura K. Donohue, New Media, Free Expression, and the Offences Against the State Acts, in The Offences Against the State Act 1939 at 80: A Model Counter-Terrorism Act? 163 (Mark Coen ed., Oxford: Hart Publishing 2021). This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, European Law Commons, Human Rights Law Commons, International Law Commons, Internet Law Commons, Legislation Commons, and the National Security Law Commons New Media, Free Expression, and the Offences Against the State Acts Laura K. Donohue1 Introduction Social media has become an integral part of modern human interaction: as of October 2019, Facebook reported 2.414 billion active users worldwide.2 YouTube, WhatsApp, and Instagram were not far behind, with 2 billion, 1.6 billion, and 1 billion users respectively.3 In Ireland, 3.2 million people (66% of the population) use social media for an average of nearly two hours per day.4 By 2022, the number of domestic Facebook users is expected to reach 2.92 million.5 Forty-one percent of the population uses Instagram (65% daily); 30% uses Twitter (40% daily), and another 30% uses LinkedIn.6 With social media most prevalent amongst the younger generations, these numbers will only rise. -

1 * Toke S. Aidt Is Reader in Economics, Faculty of Economics

WHAT MOTIVATES AN OLIGARCHIC ELITE TO DEMOCRATIZE? EVIDENCE FROM THE ROLL CALL VOTE ON THE GREAT REFORM ACT OF 1832* TOKE S. AIDT AND RAPHAËL FRANCK * Toke S. Aidt is Reader in Economics, Faculty of Economics, Austin Robinson Building, Sidgwick Avenue, CB39DD Cambridge, UK. Email: [email protected]; and CESifo, Munich, Germany. Raphaël Franck is Senior Lecturer, Department of Economics, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 91905 Jerusalem, Israel. Email: [email protected]. We thank Ann Carlos and Dan Bogart (the editors), several anonymous referees, Ekaterina Borisova and Roger Congleton as well as participants at various seminars for helpful comments. Raphaël Franck gratefully acknowledges financial support from the Adar Foundation of the Economics Department at Bar Ilan University. Raphaël Franck wrote part of this paper as Marie Curie Fellow at the Department of Economics at Brown University under funding from the People Programme (Marie Curie Actions) of the European Union's Seventh Framework Programme (FP 2007-2013) under REA grant agreement PIOF-GA-2012-327760 (TCDOFT). We are also grateful to the Cambridge Group for the History of Population and Social Structure and the ESRC (Grant RES-000-23-1579) for helping us with shape files for the maps of the ancient counties and parishes. The research was supported by the British Academy (grant JHAG097). Any remaining errors are our own. 1 WHAT MOTIVATES AN OLIGARCHIC ELITE TO DEMOCRATIZE? EVIDENCE FROM THE ROLL CALL VOTE ON THE GREAT REFORM ACT OF 1832 Abstract. The Great Reform Act of 1832 was a watershed for democracy in Great Britain. -

The Irish Soccer Split: a Reflection of the Politics of Ireland? Cormac

1 The Irish Soccer Split: A Reflection of the Politics of Ireland? Cormac Moore, BCOMM., MA Thesis for the Degree of Ph.D. De Montfort University Leicester July 2020 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements P. 4 County Map of Ireland Outlining Irish Football Association (IFA) Divisional Associations P. 5 Glossary of Abbreviations P. 6 Abstract P. 8 Introduction P. 10 Chapter One – The Partition of Ireland (1885-1925) P. 25 Chapter Two – The Growth of Soccer in Ireland (1875-1912) P. 53 Chapter Three – Ireland in Conflict (1912-1921) P. 83 Chapter Four – The Split and its Aftermath (1921-32) P. 111 Chapter Five – The Effects of Partition on Other Sports (1920-30) P. 149 Chapter Six – The Effects of Partition on Society (1920-25) P. 170 Chapter Seven – International Sporting Divisions (1918-2020) P. 191 Conclusion P. 208 Endnotes P. 216 Sources and Bibliography P. 246 3 Appendices P. 277 4 Acknowledgements Firstly, I would like to thank my two supervisors Professor Martin Polley and Professor Mike Cronin. Both were of huge assistance throughout the whole process. Martin was of great help in advising on international sporting splits, and inputting on the focus, outputs, structure and style of the thesis. Mike’s vast knowledge of Irish history and sporting history, and his ability to see history through many different perspectives were instrumental in shaping the thesis as far more than a sports history one. It was through conversations with Mike that the concept of looking at partition from many different viewpoints arose. I would like to thank Professor Oliver Rafferty SJ from Boston College for sharing his research on the Catholic Church, Dr Dónal McAnallen for sharing his research on the GAA and Dr Tom Hunt for sharing his research on athletics and cycling. -

Irish Responses to Fascist Italy, 1919–1932 by Mark Phelan

Provided by the author(s) and NUI Galway in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title Irish responses to Fascist Italy, 1919-1932 Author(s) Phelan, Mark Publication Date 2013-01-07 Item record http://hdl.handle.net/10379/3401 Downloaded 2021-09-27T09:47:44Z Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. Irish responses to Fascist Italy, 1919–1932 by Mark Phelan A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Supervisor: Prof. Gearóid Ó Tuathaigh Department of History School of Humanities National University of Ireland, Galway December 2012 ABSTRACT This project assesses the impact of the first fascist power, its ethos and propaganda, on key constituencies of opinion in the Irish Free State. Accordingly, it explores the attitudes, views and concerns expressed by members of religious organisations; prominent journalists and academics; government officials/supporters and other members of the political class in Ireland, including republican and labour activists. By contextualising the Irish response to Fascist Italy within the wider patterns of cultural, political and ecclesiastical life in the Free State, the project provides original insights into the configuration of ideology and social forces in post-independence Ireland. Structurally, the thesis begins with a two-chapter account of conflicting confessional responses to Italian Fascism, followed by an analysis of diplomatic intercourse between Ireland and Italy. Next, the thesis examines some controversial policies pursued by Cumann na nGaedheal, and assesses their links to similar Fascist initiatives. The penultimate chapter focuses upon the remarkably ambiguous attitude to Mussolini’s Italy demonstrated by early Fianna Fáil, whilst the final section recounts the intensely hostile response of the Irish labour movement, both to the Italian regime, and indeed to Mussolini’s Irish apologists. -

Franchise Extension and the British Aristocracy

Franchise Extension and the British Aristocracy Samuel Berlinski 1 Torun Dewan 2 Brenda van Coppenolle 3 Abstract. Using evidence from the Second Reform Act, introduced in the United Kingdom in 1867, we analyze the impact of extending the vote to the unskilled urban population on the composition of the Cabinet and the background characteristics of Members of Parlia- ment. Exploiting the sharp change in the electorate caused by franchise extension, we sepa- rate the effect of reform from that of underlying constituency level traits correlated with the voting population. Our results are broadly supportive of a claim first made by Laski (1928): there is no causal effect of the reform on the political role played by the British aristocracy. 1. I NTRODUCTION Does the expansion of voting rights lead to elected assemblies that are a microcosm of the societies that they represent? Or are the background characteristics of the men and women elected to office unaffected by differences in the rules governing the franchise? The question is pertinent if, as recent evidence suggests, the identity of politicians affects their subsequent performance: studies of changes in mandated forms of representation in the developing world show that identity is causally related to different outcomes (Pande, 2003); and recent contributions in political science show that background characteristics of elected MPS and cabinet ministers affects their performance. Establishing a relationship between franchise extension and the identity of elected politicians can, moreover, shed light on an intriguing puzzle in the study of political development. As noted by Aidt and Jensen (2009) there is a “growing consensus that the extension of the franchise contributed positively to the growth in government”. -

The Irish Party System Sistemul Partidelor Politice În Irlanda

The Irish Party System Sistemul Partidelor Politice în Irlanda Assistant Lecturer Javier Ruiz MARTÍNEZ Fco. Javier Ruiz Martínez: Assistant Lecturer of Polics and Public Administration. Department of Politics and Sociology, University Carlos III Madrid (Spain). Since September 2001. Lecturer of “European Union” and “Spanish Politics”. University Studies Abroad Consortium (Madrid). Ph.D. Thesis "Modernisation, Changes and Development in the Irish Party System, 1958-96", (European joint Ph.D. degree). Interests and activities: Steering Committee member of the Spanish National Association of Political Scientists and Sociologists; Steering committee member of the European Federation of Centres and Associations of Irish Studies, EFACIS; Member of the Political Science Association of Ireland; Founder of the Spanish-American Association of the University of Limerick (Éire) in 1992; User level in the command of Microsoft Office applications, graphics (Harvard Graphics), databases (Open Access) SPSSWIN and Internet applications. Abstract: The Irish Party System has been considered a unique case among the European party systems. Its singularity is based in the freezing of its actors. Since 1932 the three main parties has always gotten the same position in every election. How to explain this and which consequences produce these peculiarities are briefly explained in this article. Rezumat: Sistemul Irlandez al Partidelor Politice a fost considerat un caz unic între sistemele partidelor politice europene. Singularitatea sa este bazată pe menţinerea aceloraşi actori. Din 1932, primele trei partide politice ca importanţă au câştigat aceeaşi poziţie la fiecare scrutin electoral. Cum se explică acest lucru şi ce consecinţe produc aceste aspecte, se descrie pe larg în acest articol. At the end of the 1950s the term ‘system’ began to be used in Political Science coming from the natural and physical Sciences. -

North Central Area Committee Agenda for September

NOTIFICATION TO ATTEND MONTHLY MEETING OF THE NORTH CENTRAL AREA COMMITTEE TO BE HELD IN THE NORTHSIDE CIVIC CENTRE, BUNRATTY ROAD COOLOCK, DUBLIN 17 ON MONDAY 17th SEPTEMBER 2012 AT 2.00 P.M TO EACH MEMBER OF THE NORTH CENTRAL AREA COMMITTEE You are hereby notified to attend the monthly meeting of the above Committee to be held in the Northside Civic Centre, Bunratty Road, Coolock, Dublin 17 on 17th September 2012 at 2.00 pm to deal with the items on the agenda attached herewith. DAVE DINNIGAN AREA MANAGER Dated this the 11th September 2012 Contact Person: Ms. Dympna McCann, Ms. Yvonne Kirwan, Phone: 8166712 Northside Civic Centre, Bunratty Road, Coolock, Dublin 17. Fax: 8775851 EMAIL: [email protected] 1 Item Page Time 4467. Minutes of meeting held on the 16th July 2012 7-9 4468. Questions to Area Manager 60-68 4469. Area Matters 1hr 30mins a. Presentation from Raheny Barry Murphy/Con Clarke b. Presentation on Sutton to Sandycove Cycleway ( Con Kehely ) c. Update on North City Arterial Watermain at Clontarf/ 10-18 Hollybrook Road ( Adrian Conway ) d. Verbal update on Dublin Waste Water Treatment plant proposals.Pat Cronin e. Barnmore ( Marian Dowling ) North Central Area to write to Fingal councillors raising their concerns re Barnmore. Councillor Paddy Bourke to raise the issue of Barnmore at Regional Authority meeting on 17/7/2012. Clarify the actions open to FCC on foot of any enforcement notices being served and the likely date for the Supreme Court hearing Clarify on legal actions open to DCC on matter of permit Follow up on the carrying out of air quality and noise surveys f. -

Na Fianna Nuacht

Na Fianna Nuacht Saturday 4th March - A great day to be in the club on Mobhi Road. Lá iontach sa chlub. 9.30am Lá Glas in the Nursery - wear the green! 2pm to 6pm Fleadh na bhFiann - come on down, young and old, for music, song, dance, stories and more. Ceol, rince, amhráin is scéalta d'óg is d'aosta. 7pm to 9pm Set dancing and céilí dancing classes. Ranganna seit agus rince céilí. 9pm Céilí Mór leis an mbanna céilí Seanóg. Big Céilí dance with the céilí band Seanóg. Start St Patrick's festival with a bang on Saturday in the club! Déan teagmháil le Colum King 0876858244 or Seosamh Ó Maolalaí 0876680623. Contact Colum or Seosamh about any of the above. See link for details of what’s planned for Na Fianna tomorrow, Saturday 4th March http://bit.ly/2kVLyuF Club Shops Open Tomorrow Both shops open tomorrow, Saturday 4th March. Hurley workshop open 9-12 and Club shop open from 9-1pm in Club foyer. Na Fianna Nuacht 3ú Márta 2017 1 Na Fianna Nuacht Pitches & Weekend Fixtures ALL Na Fianna pitches are closed for the weekend. This follows heavy rain overnight and more forecasted on the way. Teams are advised to keep an eye on website http://www.clgnafianna.com/fixtures/ to see if weekend matches are on or off. Tomorrow’s Camogie Legends tournament has been cancelled. Na Fianna Nuacht 3ú Márta 2017 2 Na Fianna Nuacht Na Fianna Welcomes GAA President Elect John Horan Home Last Sunday night in the intimate surroundings of the Mobhi Suite, Uachtarán Tofa Chumann Luthchleas Gael John Horan was welcomed home by his friends. -

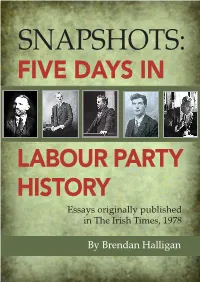

Five Days in Labour Party History by Brendan

SNAPSHOTS: FIVE DAYS IN LABOUR PARTY HISTORY Essays originally published in The Irish Times, 1978 By Brendan Halligan 1 SNAPSHOTS: FIVE DAYS OF LABOUR PARTY HISTORY By Brendan Halligan Essays originally published in The Irish Times, 1978 1. The Triumph of the Green Flag: Friday, 1 November 1918 2. The Day Labour almost came to Power: Tuesday, 16 August 1927 3. Why Labout Put DeValera in Power: 9 March 1932 4. Giving the Kiss of Life to Fine Gael: Wednesday, 18 February 1948 5. The Day the Party Died: Sunday, 13th December 1970 2 No. 1 The Triumph of the Green Flag: Friday, 1 November 1918 William O’Brien Fifteen hundred delegates jammed the Mansion House. It was a congress unprecedented in the history of the Labour Movement in Ireland. Or, in the mind of one Labour leader, in the history of the Labour movement in any country in Europe. The euphoria was forgivable. The Special Conference of the Irish Labour Party and Trade Union Congress (to give it its full name) was truly impressive, both in terms of its size and the vehemence with which it opposed the conscription a British government was about to impose on Ireland. But it was nothing compared to what happened four days later. Responding to the resolution passed by the Conference, Irish workers brought the economic life of the country to a standstill. It was the first General Strike in Ireland. Its success was total, except for Belfast. Nothing moved. Factories and shops were closed. No newspapers were printed. Even the pubs were shut. -

The Building of the State the Buildingucd and the Royal College of Scienceof on Merrionthe Street

The Building of the State The BuildingUCD and the Royal College of Scienceof on Merrionthe Street. State UCD and the Royal College of Science on Merrion Street. The Building of the State Science and Engineering with Government on Merrion Street www.ucd.ie/merrionstreet Introduction Although the Government Buildings complex on Merrion Street is one of most important and most widely recognised buildings in Ireland, relatively few are aware of its role in the history of science and technology in the country. At the start of 2011, in preparation for the centenary of the opening of the building, UCD initiated a project seeking to research and record that role. As the work progressed, it became apparent that the story of science and engineering in the building from 1911 to 1989 mirrored in many ways the story of the country over that time, reflecting and supporting national priorities through world wars, the creation of an independent state and the development of a technology sector known and respected throughout the world. All those who worked or studied in the Royal College of Science for Ireland or UCD in Merrion Street – faculty and administrators, students and porters, technicians and librarians – played a part in this story. All those interviewed as part of this project recalled their days in the building with affection and pride. As chair of the committee that oversaw this project, and as a former Merrion Street student, I am delighted to present this publication as a record of UCD’s association with this great building. Professor Orla Feely University College Dublin Published by University College Dublin, 2011. -

Download (4MB)

Grinnstaidéar ar an nGaol Gabhlánach: Anailís Shochstairiúil ar Nádúr an Dátheangachais Shochaíoch in Éirinn le linn an Fichiú hAois Gráinne Ní Bhreithiún Tá an tráchtas seo á chur faoi bhráid Ollscoil na hÉireann, Má Nuad don chéim dochtúireachta ag Gráinne Ní Bhreithiún, B.A. Scoil an Léinn Cheiltigh, Ollscoil na hÉireann, Má Nuad, Co. Chill Dara, Éire. Stiúrthóir: An Dr Tadhg Ó Dúshláine Roinn na Nua-Ghaeilge Ollamh na Nua-Ghaeilge: An tOll. Ruairí Ó hUiginn Aibreán 2014 Imleabhar 2/2 Clár an Ábhair Liosta na dTáblaí i Liosta na Léaráidí ii !! "#$%$&$'(#()*#+,-.(/0123$-,*($(45$167(869$&*(:#(;*#:<#(========================(>! 7.1! Réamhrá(========================================================================================================================(>! 7.2! Creatlach UNESCO(====================================================================================================(?! 7.3! Tabhairt Isteach na Gaeilge i Réimsí Nua Úsáide(=============================================(>@! 7.4! Tátal(=============================================================================================================================(A?! @! "#$%$&$'(#(,B+,-.(CD*#<#$D-(&0(45$167(#<36(&0(E,*9$:(F3#(================(AG! 8.1! Réamhrá(======================================================================================================================(AG! 8.2! Creatlach UNESCO(==================================================================================================(AG! 8.3! Réimse na hOibre(======================================================================================================(?>!