Rotodyne-2-Rtf-Mod.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27

A B C D E F 1 A012 A03009 125 DOMINIE 1.72 AIRCRAFT 2 A009 A05871 1804 STEAM LOCO 1.32 STEAM ENGINE 3 A013 A02447 1905 ROLLS ROYCE 1.32 CAR 4 A002 A02444 1911 ROLLS ROYCE 1.32 CAR 5 A002 A02443 1912 MODEL T FORD 1.32 CAR 6 A002 A02450 1926 MORRIS COWLEY 1.32 CAR 7 A002 A02446 1930 BENTLEY 1.32 CAR 8 ROB A20440 1930 BENTLEY 1.12 CAR 9 A028 A08440 1932 CHRYSLER IMPERIAL 1.25 CAR 10 A002 A02441 1933 ALFA ROMEO 1.32 CAR 11 A002 A01305 25PDR FIELD GUN & MORRIS QUAD 1.76 VEHICLE 12 ROB A02552 2ND DRAGOON 1815 54MM FIGURE 13 ROB 50 YEARS OF THE GREATEST PLASTIC KITS BOOK 14 A013 A02303 88MM GUN & TRACTOR 1.76 VEHICLE 15 ROB A02303 88MM GUN & TRACTOR (D-DAY) 1.76 VEHICLE 16 A026 A06012 A-10 THUNDERBOLT II 1.72 AIRCRAFT 17 ROB ITALERI 097 A-10 WARTHOG 1.72 AIRCRAFT 18 A026 REVELL 04206 A300-600 ST BELUGA 1144 AIRCRAFT 19 A008 A01028 A6M2 ZERO (VJ DAY) 1.72 AIRCRAFT 20 ROB A50127 A6M2B -21 (2011) 1.72 AIRCRAFT PAINTS IN BOX 21 ROB A01005 A6M2B ZERO 1.72 AIRCRAFT 22 A031 REVELL 4366 A-7A CORSAIR 1.72 AIRCRAFT 23 A007 A04211 ADMIRAL GRAF SPEE 1600 SHIP 24 ROB A01314 AEC MATADOR (D-DAY) 1.76 VEHICLE 25 A026 A04046 AH-1 T SEA COBRA 1.72 HELICOPTER 26 A005 A03077 AH-64 APACHE LONGBOW 1.72 HELICOPTER 27 A014 A07101 AH-64 APACHE LONGBOW 1.48 HELICOPTER 28 A026 A04044 AH-64 APACHE LONGBOW 1.72 HELICOPTER 29 A008 A02014 AICHI D3AI VAL (VJ DAY) 1.72 AIRCRAFT 30 ROB AIRFIX 1972 CATALOUGE BOOK 31 ROB AIRFIX 1974 CATALOUGE BOOK 32 ROB AIRFIX 1983 CATALOUGE BOOK 33 ROB A78183 AIRFIX 2007 CATALOUGE BOOK 34 ROB A78184 AIRFIX 2008 CATALOUGE BOOK 35 ROB AIRFIX CLUB -

Assessment of Navy Heavy-Lift Aircraft Options

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available from www.rand.org as a public CHILD POLICY service of the RAND Corporation. CIVIL JUSTICE EDUCATION Jump down to document ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT 6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit research NATIONAL SECURITY POPULATION AND AGING organization providing objective analysis and effective PUBLIC SAFETY solutions that address the challenges facing the public SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY and private sectors around the world. SUBSTANCE ABUSE TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Support RAND WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore RAND National Defense Research Institute View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non- commercial use only. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. This product is part of the RAND Corporation documented briefing series. RAND documented briefings are based on research briefed to a client, sponsor, or targeted au- dience and provide additional information on a specific topic. Although documented briefings have been peer reviewed, they are not expected to be comprehensive and may present preliminary findings. Assessment of Navy Heavy-Lift Aircraft Options John Gordon IV, Peter A. Wilson, Jon Grossman, Dan Deamon, Mark Edwards, Darryl Lenhardt, Dan Norton, William Sollfrey Prepared for the United States Navy Approved for public release; unlimited distribution The research described in this report was prepared for the United States Navy. -

National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics

NATIONAL ADVISORY COMMITTEE FOR AERONAUTICS TECHNICAL NOTE 2154 AN ANALYSIS OF TIlE AUTOROTATIVE PERFORMANCE OF A BELICOPTER POWERED BY ROTOR-TIP JET UN[TS By Alfred Gessow Langley Aeronautical Laboratory Langley Air Force Base, Va. Washington July 1950 NATIONAL ADVISORY COMMITTEE FOR AERONAUTICS TECHNICAL NOTE 2l AN ANALYSIS OF THE AUTOROTATIVE PERFORMANCE OF A HELICOPTER POWERED BY ROTOR-TIP JET UNITS By Alfred Gessow SUMMARY The autorotative performance of an assumed helicopter was studied to determine the effect of inoperative jet units located at the rotor- blade tip on the helicopter rate of descent. For a representative ram- jet design, the effect of the jet drag is to increase the minimum rate of descent of the helicopter from about l,OO feet per minute to 3,700 feet per minute when the rotor is operating at a tip speed of approximately 600 feet per second. The effect is less if the rotor operates at lower tip speeds, but the rotor kinetic energy and the stall margin available for the landing maneuver are then reduced. Power-off rates of descent of pulse-jet helicopters would be expected to be less than those of ram- jet.helicopters because pulse jets of current design appear to have greater ratios of net power-on thrust to power-off, drag than currently designed rain jets. Iii order to obtain greater accuracy in studies of autorotative per- forimance, calculations in'volving high power-off rates of descent should include the weight-supporting effect of the fuselage parasite-drag force and the fact that the rotor thrust does not equal the weight of the helicopter. -

Roy L. Clough, Jr

Model air car skims the ground By ROY L. CLOUGH, JR. Working model of a ground-effect vehicle rides on a cushion of air from a model-airplane engine Tethered to a stake, the car will skim half an inch or so off the ground, around and around until it runs out of fuel WITH A hollow whistling note audible over the whine of its tiny engine, this advanced working model of a ground-effect vehicle skims across the floor supported on a cushion of air. What makes it go? is a model, which can buzz along at a good clip Air is supplied by a prop to a peripheral slot, on any level surface with a minimum of sideslip which produces a high-speed wall of air around due to minor irregularities on the surface. the edge of the model to retain the lift. A Attached to a tether it will whiz merrily around in separate propulsion-system tube bleeds off air a circle until the fuel runs out. It rides a half-inch for reactive propulsion---from the blower section, or so off the floor even when running free. Any not the skirt. Supporting pressure is not reduced small airplane engine can be used to power it. If --- a major fault of ground-effect vehicles which you use the engine installed in the original propel by dumping air pressure and lifting the model, which is supplied with a three-blade skirt on the opposite side from the desired prop, you won't have to make a prop of sheet direction of travel. -

Over Thirty Years After the Wright Brothers

ver thirty years after the Wright Brothers absolutely right in terms of a so-called “pure” helicop- attained powered, heavier-than-air, fixed-wing ter. However, the quest for speed in rotary-wing flight Oflight in the United States, Germany astounded drove designers to consider another option: the com- the world in 1936 with demonstrations of the vertical pound helicopter. flight capabilities of the side-by-side rotor Focke Fw 61, The definition of a “compound helicopter” is open to which eclipsed all previous attempts at controlled verti- debate (see sidebar). Although many contend that aug- cal flight. However, even its overall performance was mented forward propulsion is all that is necessary to modest, particularly with regards to forward speed. Even place a helicopter in the “compound” category, others after Igor Sikorsky perfected the now-classic configura- insist that it need only possess some form of augment- tion of a large single main rotor and a smaller anti- ed lift, or that it must have both. Focusing on what torque tail rotor a few years later, speed was still limited could be called “propulsive compounds,” the following in comparison to that of the helicopter’s fixed-wing pages provide a broad overview of the different helicop- brethren. Although Sikorsky’s basic design withstood ters that have been flown over the years with some sort the test of time and became the dominant helicopter of auxiliary propulsion unit: one or more propellers or configuration worldwide (approximately 95% today), jet engines. This survey also gives a brief look at the all helicopters currently in service suffer from one pri- ways in which different manufacturers have chosen to mary limitation: the inability to achieve forward speeds approach the problem of increased forward speed while much greater than 200 kt (230 mph). -

Rotor Spring 2018

Departments Features Index of Advertisers Spring 2018 rotor.org Serving the International BY THE INDUSTRY Helicopter Community FOR THE INDUSTRY Grand Canyon Helitack The Best Job in Aviation? What’s In Your Jet Fuel? p 58 Vietnam Pilots and Crew Members Honored p 28 Make the Connection March 4–7, 2019 • Atlanta Georgia World Congress Center Exhibits Open March 5–7 Apply for exhibit space at heliexpo.rotor.org LOTTERY 1* Open to HAI HELI-EXPO 2018 Exhibitors APPLY BY June 22, 2018 WITH PAYMENT LOTTERY 2 Open to All Companies APPLY BY Aug. 10, 2018 WITH PAYMENT heliexpo.rotor.org * For information on how to upgrade within Lottery 1, contact [email protected]. EXHIBIT NOW FALCON CREST AVIATION PROUDLY SUPPLIES & MAINTAINS AVIATION’S BEST SEALED LEAD ACID BATTERY RG-380E/44 RG-355 RG-214 RG-222 RG-390E RG-427 RG-407 RG-206 Bell Long Ranger Bell 212, 412, 412EP Bell 407 RG-222 (17 Ah) or RG-224 (24 Ah) RG-380E/44 (42 Ah) RG-407A1 (27 Ah) Falcon Crest STC No. SR09069RC Falcon Crest STC No. SR09053RC Falcon Crest STC No. SR09359RC Airbus Helicopters Bell 222U Airbus Helicopters AS355 E, F, F1, F2, N RG-380E/44 (42 Ah) BK 117, A-1, A-3, A-4, B-1, B-2, C-1 RG-355 (17 Ah) Falcon Crest STC No. SR09142RC RG-390E (28 Ah) Falcon Crest STC No. SR09186RC Falcon Crest STC No. SR09034RC Sikorsky S-76 A, C, C+ Airbus Helicopters RG-380E/44 (42 Ah) Airbus Helicopters AS350B, B1, B2, BA, C, D, D1 Falcon Crest STC No. -

The Fairey Rotodyne

THE FAIREY ROTODYNE The Rotodyne represents an entirely new approach to air transport, and its amazing performance is a triumph for the British Au.i4.ii Industry. It is the first true vertical take-off airliner, and is capable of carrying a full load of passengers or freight, operating from airlicUU no larger than two tennis courts. Unlike the conventional helicopter the Rotodyne is economical to operate, and also capable of much hijr.lin speeds and greater range. The prototype Rotodyne, built under a Ministry of Supply contract, first flew on 6th November, 1957, and achieved its first transition to complete autorotative flight in April, 1958. This prototype, the subject of this model, is capable of carrying 48 passengers or five tun» of freight; the eventual production version will be larger, carrying up to 70 passengers or 8 tons of freight, and will be powered by the more powerful Rolls-Royce Tyne engines in place of the present Elands. A striking demonstration of the Rotodyne's performance was given in January, 1959, when it set up a record 191 m.p.h. on a 100 kin closed circuit. This exceeds the previous record by 49 m.p.h.j and is even 29 m.p.h. faster than the previous absolute speed record for heli- copters. This speed, together with the range of 450 miles, to be increased to 650 miles in the developed version, and of course the weighi lifting and vertical take-off performance, puts the Fairey Rotodyne into a class of its own. Already three airline operators have indicated their intention of buying the Rotodyne, and great interest is being shown by civilian and military operators throughout Europe and America. -

The Dynamic Performance of a Rotating Frustum of a Cone*

Sixth International Symposium on Marine Propulsors smp’19, Rome, Italy, May 2019 The Dynamic Performance of a Rotating Frustum of a cone* Hu Jiangping1,2, Wang Yanxia1,2, Wei Jinfang 1,2, Chen Jingpu 1,2 1China Ship Scientific Research Center (CSSRC), Wuxi, China 1Jiangsu Key Laboratory of Green Ship Technology, Wuxi, China ABSTRACT vessel "DeltaChallenger" during the Nor-Shipping 2015 Flettner rotor is a wind-assisted ship propulsion device exhibition. To reduce fuel consumption the vessel has six and it could be used to decrease the fuel consumption. rotor six rotor sails, giving 10% of the total propulsion The lift coefficient of the traditional Flettner rotor power. Norsepower, founded in 2012, aimed to reduce the increases with the increasing spinning ratio. So it is better environmental impact of shipping by providing its Rotor to hire a high spinning ratio to obtain high lift force. Sail Solution technology, had installed the rotors on the However, the corresponding spinning ratio to the Ro-Ro, Cruise ferry and Tanker. maximum lift-drag ratio is around 2 and the lift-drag ratio decreases when the spinning ratio exceeds 2. So hiring high rotation rate is not economical. In this paper, we propose a new type of rotors composed of rotating frustum of a cone and Thom disc. The numerical investigation reveals that at high spinning ratio, the new rotor could not only maintain high lift coefficient, but also get high lift-drag ratio and the practicability is highly enhanced. And the performance of the rotating frustum is then investigated thoroughly. Keywords Flettner rotor, wind-assisted ship propulsion, lift-drag ratio Figure 1 Photograph of Flettner’s rotor ship Baden-Baden 1 INTRODUCTION In 1926, a vessel, named the Baden-Baden, sailed across Flow around a non-rotating cylinder has been subjected to the Atlantic, with its sails replaced by twin rotatable decades of research due to its complicated wake flow, cylinders, as shown in Figure 1. -

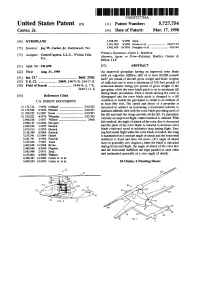

E. E. W.M. PE Velocity Animproved Fight Control Method Is Utilized With

US00572.7754A United States Patent (19) 11 Patent Number: 5,727,754 Carter, Jr. 45) Date of Patent: Mar. 17, 1998 (54 GYROPLANE 4,928,907 5/1990 Zuck, 5,301,900 4/1994 Groen et al. ......................... 244,1725 75) Inventor: Jay W. Carter, Jr. Burkburnett, Tex. 5,462,409 10/1995 Frengley et al. ........................ 416/144 Primary Examiner-Galen L. Barefoot 73) Assignee: CarterCopters, L.L.C.. Wichita Falls, Attorney, Agent, or Fi Felsman, Bradley, Gunter & Tex. Dillon, LLP (21) Appl. No.: 521,690 57 ABSTRACT 22 Filed: Aug. 31, 1995 An improved gyroplane having an improved rotor blade (51) int. Clar. inchwith anper edgewise pound of stiffness aircraft gross(E) ofweight at least and 80,000 blade weightspounds (52) 244/8: 244/75 R; 24.4/17.11 of sufficient size to store a minimum of 100 foot pounds of 58) Field of Search .............................. 244/4 R., 6, 7 R. rotational kinetic energy per pound of gross weight of the 244/17.118 gyroplane while the rotor blade pitch is set to minimum lift during blade prerotation. Then a clutch driving the rotor is 56) References Cited disengaged and the rotor blade pitch is changed to a lift U.S. PATENT DOCUMENTS condition to enable the gyroplane to climb to an altitude of at least fifty feet. The speed and thrust of a propeller is D. 172,712 7/1954 Gebhard ................................. D2/335 increased to achieve an increasing a horizontal velocity to D. 178,598 8/1956 Fletcher. P22 maintain altitude, first with the rotor blade providing most of D. -

Development of a Helicopter Vortex Ring State Warning System Through a Moving Map Display Computer

Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis Collection 1999-09 Development of a helicopter vortex ring state warning system through a moving map display computer Varnes, David J. Monterey, California. Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/26475 DUDLEY KNOX LIBRARY NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY CA 93943-5101 NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL Monterey, California THESIS DEVELOPMENT OF A HELICOPTER VORTEX RING STATE WARNING SYSTEM THROUGH A MOVING MAP DISPLAY COMPUTER by David J. Varnes September 1999 Thesis Advisor: Russell W. Duren Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington. VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget. Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188) Washington DC 20503. REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED 1. agency use only (Leave blank) September 1999 Master's Thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. FUNDING NUMBERS DEVELOPMENT OF A HELICOPTER VORTEX RING STATE WARNING SYSTEM THROUGH A MOVING MAP DISPLAY COMPUTER 6. AUTHOR(S) Varnes, David, J. 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) PERFORMING ORGANIZATION Naval Postgraduate School REPORT NUMBER Monterey, CA 93943-5000 10. -

A Review of the Magnus Effect in Aeronautics

Progress in Aerospace Sciences 55 (2012) 17–45 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Progress in Aerospace Sciences journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/paerosci A review of the Magnus effect in aeronautics Jost Seifert n EADS Cassidian Air Systems, Technology and Innovation Management, MEI, Rechliner Str., 85077 Manching, Germany article info abstract Available online 14 September 2012 The Magnus effect is well-known for its influence on the flight path of a spinning ball. Besides ball Keywords: games, the method of producing a lift force by spinning a body of revolution in cross-flow was not used Magnus effect in any kind of commercial application until the year 1924, when Anton Flettner invented and built the Rotating cylinder first rotor ship Buckau. This sailboat extracted its propulsive force from the airflow around two large Flettner-rotor rotating cylinders. It attracted attention wherever it was presented to the public and inspired scientists Rotor airplane and engineers to use a rotating cylinder as a lifting device for aircraft. This article reviews the Boundary layer control application of Magnus effect devices and concepts in aeronautics that have been investigated by various researchers and concludes with discussions on future challenges in their application. & 2012 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Contents 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................18 1.1. History .....................................................................................................18 -

A Qualitative Introduction to the Vortex-Ring-State, Autorotation, and Optimal Autorotation

36th European Rotorcraft Forum, Paris, France, September 7-9, 2010 Paper Identification Number 089 A Qualitative Introduction to the Vortex-Ring-State, Autorotation, and Optimal Autorotation Skander Taamallah ∗† ∗ Avionics Systems Department, National Aerospace Laboratory (NLR) 1059 CM Amsterdam, The Netherlands ([email protected]). † Delft Center for Systems and Control (DCSC) Faculty of Mechanical, Maritime and Materials Engineering Delft University of Technology, 2628 CD Delft, The Netherlands. Keywords: Vortex-Ring-State (VRS); autorotation; Height-Velocity diagram; optimal control; optimal autorotation Abstract: The main objective of this pa- 1 Introduction per is to provide the reader with some qualita- tive insight into the areas of Vortex-Ring-State This paper summarizes the results of a brief (VRS), autorotation, and optimal autorota- literature survey, of relevant work in the open tion. First this paper summarizes the results literature, covering the areas of the VRS, of a brief VRS literature survey, where the em- autorotation, and optimal autorotation. Due phasis has been placed on a qualitative descrip- to time and space constraints, only published tion of the following items: conditions leading accounts relative to standard helicopter to VRS flight, the VRS region, avoiding the configurations will be covered, omitting thus VRS, the early symptoms, recovery from VRS, other types such as tilt-rotor, side-by-side, experimental investigations, and VRS model- tandem, and co-axial. Presenting a complete ing. The focus of the paper is subsequently survey of a field as diverse as helicopter VRS, moved towards the autorotation phenomenon, autorotation, and optimal trajectories in where a review of the following items is given: autorotation is a daunting task.