Minimum Cash Wages, Tipped Restaurant Workers, and Poverty*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Should New York State Eliminate Its Subminimum Wage?

POLICY BRIEF April 20, 2018 Should New York State Eliminate its Subminimum Wage? Sylvia A. Allegretto Sylvia A. Allegretto, Ph.D., is an economist and Chair of the Center on Wage and Employment Dynamics at the Institute for Research on Labor and Employment, University of California, Berkeley ([email protected]). The author is grateful for funding from the Ford Foundation. Center on Wage and Employment Dynamics Should New York State Eliminate its Subminimum Wage? 1 Introduction Low-wage workers and their supporters in New York received good news when the state enacted a new minimum wage bill in 2016. Minimums for New York City and the counties of Long Island and Westchester are now slated to be $15—and will be phased in by 2022 at the latest. The balance of New York State has annual increases scheduled for a final phase-in to $12.50 on the last day of 2020.1 Until rather recently, minimum wage policy and debate often left out the subminimum wage workforce that relies on tips as part of their wage.2 In 2016, New York could have joined the ranks of the seven states that do not allow tipped workers to be paid a sub-wage, but wound up leaving them out of the new policy. In late 2017, however, Governor Cuomo unveiled a proposal to examine how economic justice would be strengthened if the state eliminated the subminimum wage (also known as the tipped minimum wage).3 As a result, the NYS Department of Labor has scheduled public hearings across the state beginning in spring 2018. -

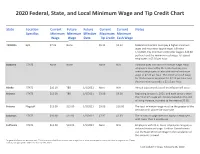

2020 Federal, State, and Local Minimum Wage and Tip Credit Chart

2020 Federal, State, and Local Minimum Wage and Tip Credit Chart State Location Current Future Future Current Current Notes Specifics Minimum Minimum Effective Maximum Minimum Wage Wage Date Tip Credit Cash Wage FEDERAL N/A $7.25 None $5.12 $2.13 Federal contractors must pay a higher minimum wage and respective tipped wage. Effective 1/1/2020, this minimum contractor wage is $10.80 per hour and the minimum cash wage for tipped employees is $7.55 per hour. Alabama STATE None None None N/A Alabama does not have a minimum wage. Most employers covered by the FLSA must pay non- exempt employees at least the federal minimum wage of $7.25 per hour. The minimum cash wage for FLSA-covered employers is $2.13 per hour and the maximum tip credit is $5.12 per hour. Alaska STATE $10.19 TBD 1/1/2021 None N/A Annual adjustments based on inflation will occur. Arizona STATE $12.00 TBD 1/1/2021 $3.00 $9.00 Beginning January 1, 2021, and each January after, the minimum wage will increase based on the cost of living increase, rounded to the nearest $0.05. Arizona Flagstaff $13.00 $15.00 1/1/2021 $3.00 $10.00 The local minimum wage must be the greater of the set rate or $2 above the state rate. Arkansas STATE $10.00 $11.00 1/1/2021 $7.37 $2.63 The minimum wage does not apply to employers with fewer than 4 employees. California STATE $13.00 $14.00 1/1/2021 None N/A Employers with 25 or fewer employees may pay a reduced minimum wage. -

New Jersey: 4Th State to Adopt $15 Minimum Wage

th New Jersey: 4 State to Adopt $15 Volume 42 Minimum Wage Issue 14 February 12, 2019 On February 4, New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy signed a bill into law that will gradually increase the minimum wage for Authors most employees working in the state to $15 an hour by 2024. Nancy Vary, JD Employers with at least six employees will have to adjust their Abe Dubin, JD payroll systems and pay practices to ensure compliance with the first rate increase on July 1. Background In 2013, New Jersey voters approved a constitutional amendment to raise the state minimum wage from $7.25 — the federal minimum wage rate — to $8.25 an hour in 2014, and to add automatic cost- of-living increases each year based on the consumer price index for urban wage earners and clerical workers (CPI-W). Since then, efforts to further increase the minimum wage have continued but have been unsuccessful. In 2016, then Gov. Chris Christie vetoed a bill that would have raised New Jersey's minimum wage to $10.10 an hour in 2017 and to at least $15 an hour over the following five years. While many in the business community have expressed concern that rate hikes would hit companies’ bottom lines, increase job loss, and lead to more automation, lawmakers in a number of states are considering raising the minimum wage. For example, last month bills to raise the minimum wage to $15 an hour were introduced in Hawaii, New Mexico, and Maryland. On February 5, the Democratic- controlled Illinois Senate approved increasing the state's $8.25 hourly minimum wage to $15 over six years. -

Alabama Minimum Wage Laws

Alabama minimum wage laws Localities with minimum wage different than state minimum wage City with different minimum wage ■ County with different minimum wage State minimum wage laws Minimum wage None - Federal minimum wage of $7.25 applies Tipped wage None - Federal tipped wage of $2.13 applies Most recent increase n/a Most recent major change n/a to minimum wage law Upcoming increases n/a Indexing n/a Notes n/a Alaska minimum wage laws Localities with minimum wage different than state minimum wage City with different minimum wage ■ County with different minimum wage State minimum wage laws Minimum wage $10.19 Tipped wage $10.19 Most recent increase $9.89 to $10.19, effective January 1, 2020 Most recent major change 2014, by ballot measure to minimum wage law Upcoming increases Annual indexing effective January 1 Indexing Annual increases based on the percentage change in the CPI-U for the Anchorage metropolitan area. Notes n/a Arizona minimum wage laws Localities with minimum wage different than state minimum wage City with different minimum wage ■ County with different minimum wage State minimum wage laws Minimum wage $12.00 Tipped wage $9.00 Most recent increase $11.00 to $12.00, effective January 1, 2020 Most recent major change 2016, by ballot measure to minimum wage law Upcoming increases Annual indexing beginning January 1, 2021 Indexing Annual increases based on the percentage change in the Consumer Price Index for Urban Wage Earners and Clerical Workers (CPI-W), U.S. city average Notes n/a Flagstaff $13.00 minimum wage, $10.00 -

Estimating the Impact of a $15.00 Minimum Wage in Florida

September 2020 Estimating the Impact of a $15.00 Minimum Wage in Florida Technical Analysis By: Dr. William Even, Miami University Dr. David Macpherson, Trinity University Prepared with support from Save Florida Jobs, Inc. The economists retained sole control over their technical analysis. About the Economists DR. DAVID MACPHERSON is the E.M. Stevens Professor of Economics at Trinity University, where he also serves as department chair. Prior to joining Trinity University, he held the Rod and Hope Brim Eminent Scholar Chair in Economics, and was Director of the Pepper Institute on Aging and Public Policy at Florida State University. Earlier, he served as an assistant and associate professor of economics at Miami University. Macpherson’s research has been concentrated on examining factors that cause deviations from wage equalization. In particular, he has focused on the role of trade unions, pensions, wage discrimination, industry deregulation, and the minimum wage. Macpherson has written over 60 journal articles and book chapters. He is a co-author of the undergraduate textbooks Economics: Private and Public Choice and Contemporary Labor Economics. He also co-authored the book Pensions and Productivity. With Barry Hirsch, he provides union data to researchers and the public through the web site www.unionstats.com. DR. WILLIAM EVEN is a Professor of Economics in the Farmer School of Business at Miami University. He received his Ph.D. in economics from the University of Iowa in 1984. He is a research fellow with the Scripps Gerontology Center, the Employee Benefits Research Institute and the Institute for the Study of Labor. His recent research examines the effects of minimum wage laws, the Affordable Care Act, the effect of Greek affiliation on academic performance, and the relationship between skills and earnings among older workers. -

2021 Minimum Wage Increases Upd

The following states and municipalities will raise the minimum wage in 2021. NOTES & FUTURE STATE OR MINIMUM WAGE MAXIMUM MINIMUM SCHEDULED LOCALITY RATE TIP CREDIT TIPPED WAGE INCREASES FEDERAL $7.25 $5.12 $2.13 Tipped employees must MINIMUM regularly earn at least $30 per month in tips. FEDERAL $10.95 $3.30 $7.65 CONTRACTORS Alabama $7.25* Federal law applies Federal law applies Alaska $10.34 Tip credit prohibited Tip credit prohibited Arizona $12.15 $3.00 $9.15 Flagstaff $15.00 ** ** Arkansas $11.00 $8.37 $2.63 Tipped employees must regularly earn at least $20 per month in tips. California $14.00 for businesses with Tip credit prohibited Tip credit prohibited 26 employees or more; $13.00 for businesses with fewer than 26 employees Alameda $15.00 ** ** Belmont $15.90 ** ** Berkeley $16.07 ** ** Burlingame $15.00 Cupertino $15.65 ** ** Daly City $15.00 ** ** El Cerrito $15.61 ** ** Emeryville $16.84 ** ** $13.50 for small employers ** ** Increasing to $15 for (25 or fewer employees); Fremont small employers $15.00 for large employers effective 07/01/21. (26 or more employees) ** ** Half Moon Bay $15.00 $15.00 for businesses with ** ** 26 employees or more; Hayward $14.00 for businesses with fewer than 26 employees Client Alert: 2021 Minimum Wage Increases Upd. Dec. 2020 NOTES & FUTURE STATE OR MINIMUM WAGE MAXIMUM MINIMUM SCHEDULED LOCALITY RATE TIP CREDIT TIPPED WAGE INCREASES $15.47 for hourly hotel ** ** workers; Long Beach . $15.30 for hourly concessionaire workers Los Altos $15.65 ** ** $15.00 for businesses with ** ** 26 or more employees; $14.25 for businesses with 25 or fewer employees or Increasing to $15 for Los Angeles City and non-profit corporations with businesses with 25 or County 26 or more employees with fewer employees approval to pay a deferred effective 07/01/21. -

Restaurants Flourish with One Fair Wage

BETTER WAGES, BETTER TIPS Restaurants Flourish with One Fair Wage FEBRUARY 13, 2018 BY RESTAURANT OPPORTUNITIES CENTERS UNITED BETTER WAGES, BETTER TIPS: Restaurants Flourish with One Fair Wage THERE ARE SIX MILLION TIPPED WORKERS ACROSS THE NATION, the vast majority women and disproportionately workers of color.1 Under federal law these workers can be paid as little as $2.13 an hour, with the remainder of their income derived solely from tips. As a result, tipped workers live in poverty and depend on food stamps at rates twice that of the general population.2 Since 1996, when the tipped subminimum wage was frozen at $2.13, workers have been abandoned by federal wage policy. Seven states have adopted equal treatment for tipped workers ensuring all workers one fair wage, independent of tips. In those seven states: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY EXECUTIVE • Sexual harassment is lower than in the subminimum wage states that maintain an unequal treatment regime. Tipped women workers who earn a guaranteed wage report half the rate of sexual harassment as women in states with a $2.13 minimum wage since they do not have to accept inappropri- ate behavior from customers to guarantee an income (Figure A). Tipped women FIGURE A workers in $2.13 states report that they are three times more likely to be told by INCIDENCE OF SEXUAL HARASSMENT management to alter their appearance and to wear ‘sexier,’ more revealing clothing BY WAGE REGION (±2*SE) than women in equal treatment states.3 Workers in equal treatment (OFW) states experience half the rate of total sexual • Wages including tips are unambiguously higher than in the 43 harassment, compared to workers in unequal states that maintain an unequal treatment regime. -

State Wage Rates for State Minimum Wage and Tipped Employees

CURRENT AND FUTURE STATE WAGE RATES FOR STATE MINIMUM WAGE AND TIPPED EMPLOYEES December 2018 2019 State Minimum and Tipped Wage Rates Current rate and planned increases (Unless otherwise noted) States and localities in BOLD represent rates above the federal minimum wage. *Official wage rates unannounced - these are estimates STATE/ TIPPED MINIMUM EFFECTIVE NOTES LOCALITY WAGE WAGE DATES Alabama $2.13 $7.25 Current Alabama has no state minimum wage law; federal law applies. Alaska $9.84 $9.84 Current Future increases will be indexed. $9.89 $9.89 1/1/2019 Arizona $7.50 $10.50 Current In November 2016, Arizona voters approved a $8.00 $11.00 1/1/2019 ballot initiative that would take the state’s wage to $12 by 2020. Annual Indexing will return in 2021. $9.00 $12.00 1/1/2020 Arizona’s tip credit is $3.00. Arkansas $2.63 $8.50 Current Arkansas’s cash wage is frozen at $2.63. In November $2.63 $9.25 1/1/2019 2018, voters approved a series of annual minimum wage $2.63 $10.00 1/1/2020 increases with the wage reaching $11.00 by 2021. $2.63 $11.00 1/1/2021 California $11.00 $11.00 Current $12.00 $12.00 1/1/2019 California allows no tip credit. Businesses with 25 or fewer employees will have an extra year to $13.00 $13.00 1/1/2020 comply. The wage will be indexed to inflation starting $14.00 $14.00 1/1/2021 1/1/2023. $15.00 $15.00 1/1/2022 Colorado $7.18 $10.20 Current In November 2017, Colorado’s voters approved a $8.08 $11.10 1/1/2019 ballot initiative that will take the state’s wage to $8.98 $12.00 1/1/2020 $12 by 2020. -

Women Fare Better in States with Equal Treatment for Tipped Workers

& NATIONAL WOMEN’S LAW CENTER & RESTAURANT OPPORTUNITIES CENTERS UNITED FACT SHEET | OCTOBER 2016 WORKPLACE JUSTICE RAISE THE WAGE: WOMEN FARE Key Facts BETTER IN STATES WITH EQUAL In equal treatment states, compared to states with a tipped minimum cash wage of $2.13 per hour: TREATMENT FOR TIPPED • The wage gap for women overall working full time, year WORKERS round is 19 percent smaller. The federal minimum cash wage for tipped workers has been frozen at $2.13 per hour for 25 years, and now represents • The wage gap for women in tipped occupations is 33 less than a third of the federal minimum wage ($7.25 per percent smaller. 1 hour)—its lowest share ever. Given this, it is unsurprising • The poverty rate for women overall is 13 percent lower. that poverty rates for tipped workers are more than twice as high as rates for workers overall.2 Women, who represent • The poverty rate for African American women is 8 percent two-thirds of tipped workers nationally, are hit especially hard lower. by this poverty level wage.3 In fact, women’s concentration in • The poverty rate for Latina women is 13 percent lower. tipped occupations and other low-wage jobs is an important factor contributing to the persistent gender wage gap: • The poverty rate for women in tipped occupations is 27 women working full time, year round typically are paid just percent lower. 80 percent of what their male counterparts are paid—and the • The poverty rate for women of color in tipped occupations wage gap is even wider for women of color.4 is 31 percent lower. -

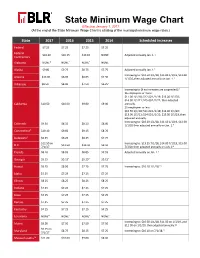

BLR State Minimum Wage Chart

State Minimum Wage Chart Effective January 1, 2017 (At the end of the State Minimum Wage Chart is a listing of the municipal minimum wage rates.) State 2017 2016 2015 2014 Scheduled Increases Federal $7.25 $7.25 $7.25 $7.25 Federal $10.20 $10.15 $10.10 NONE Adjusted annually Jan. 1. 1 Contractors Alabama NONE* NONE* NONE* NONE Alaska $9.80 $9.75 $8.75 $7.75 Adjusted annually Jan. 1.2 Increasing to: $10.50 1/1/18, $11.00 1/1/19, $12.00 Arizona $10.00 $8.05 $8.05 $7.90 1/1/20, then adjusted annually on Jan. 1.3 Arkansas $8.50 $8.00 $7.50 $6.25* Increasing to (if no increases are suspended):4 26 employees or more: $11.00 1/1/18; $12.00 1/1/19; $13.00 1/1/20; $14.00 1/1/21; $15.00 1/1/22, then adjusted California $10.50 $10.00 $9.00 $9.00 annually. 25 employees or less: $10.50 1/1/18; $11.00 1/1/19; $12.00 1/1/20; $13.00 1/1/21; $14.00 1/1/22; $15.00 1/1/23, then adjusted annually. Increasing to: $10.20 1/1/18, $11.10 1/1/19, $12.00 Colorado $9.30 $8.31 $8.23 $8.00 1/1/20 then adjusted annually on Jan. 1.5 Connecticut6 $10.10 $9.60 $9.15 $8.70 Delaware7 $8.25 $8.25 $8.25 $7.75 $12.50 on Increasing to: $13.25 7/1/18, $14.00 7/1/19, $15.00 D.C. -

Frequently Asked Questions Related to the $15 Minimum Wage 55% Full-Time 90% Age 20+ 56% Women

May 31, 2017 Frequently Asked Questions Related to the $15 Minimum Wage By Nicole Rodriguez Updated January 2018 In a well-functioning economy, people who work full time should be able to earn enough to support themselves and their families. That’s important for families and for the overall economy, which relies on consumer spending to keep local businesses thriving. Unfortunately, the pattern of economic growth between the end of the Second World War and the 1970s – where wages generally grew at the same pace as economic productivity – has changed in recent decades. Since the 1970s, the value of wages for most workers has been stagnant while the benefits of economic growth have gone disproportionately to the highest income households.1 In recent years, minimum wage increases have begun to restore modest wage growth for lower wage workers.2 A number of states have now adopted laws to create a $15 minimum wage to spread these gains more widely. This brief discusses commonly asked questions surrounding a $15 minimum wage in Massachusetts. Who would be affected by a minimum wage increase to $15 in Massachusetts? Projections show that increasing the minimum wage from its current $11 level by $1 an hour until $15 in 2022 would raise the wages of about 943,000 workers or 29 percent of the workforce statewide. Of these affected workers, 90 percent are adults (20 years old and older), 56 percent are women, and 55 percent work full-time. Additionally, one quarter of all working parents would see a raise. And about 367,000 kids statewide (or 26 percent of all Massachusetts children) have at least one working parent that would get a raise. -

WRRB-Minimum-Wage-Ja

Minimizing Risk The Implications of a $15 Minimum Wage for Worcester Report 18-01 January 2018 Research in the Public Interest Research Worcester Regional Research Bureau, Inc. 500 Salisbury Street, Worcester, MA 01609 • 508-799-7169 • www.wrrb.org Minimizing Risk Introduction Current Wage Laws Employers and workers have been in a tug-of-war The minimum wage in Worcester is $11 per hour, over working conditions and benefits for as long as required by Massachusetts law. Unlike as formalized employment has existed. But the communities in some other states, municipalities government’s involvement in creating labor laws in Massachusetts do not have the power to and regulating how companies treat their establish local wage minimums on their own. employees is relatively new. The U.S. Department of Labor was created in 1913, and it would take until 1938 for such innovations as paid overtime, The first U.S. minimum wage established in 1938 child labor restrictions, and a federal minimum was $0.25 per hour, equivalent to $4.32 in 2017 wage to become national law. after adjusting for inflation. The minimum wage sets the base hourly compensation that can legally be offered to employees. In a speech While most “Fair Labor Standards,” as the 1938 introducing the Fair Labor Standards Act, Act termed them, are accepted without complaint President Franklin Roosevelt said that “all but by all involved, the minimum wage has been a the hopelessly reactionary will agree that to regular topic of debate over the years. Labor conserve our primary resources of man power, advocates argue the current rates are too low, government must have some control over positing that a higher minimum would ensure a maximum hours, minimum wages, the evil of better quality of life for struggling workers and child labor and the exploitation of unorganized likely benefit the economy, increasing purchasing labor.” power for millions of Americans and keeping people off taxpayer-funded welfare programs.