Minimum Wage Basics: Overview of the Tipped Minimum Wage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Should New York State Eliminate Its Subminimum Wage?

POLICY BRIEF April 20, 2018 Should New York State Eliminate its Subminimum Wage? Sylvia A. Allegretto Sylvia A. Allegretto, Ph.D., is an economist and Chair of the Center on Wage and Employment Dynamics at the Institute for Research on Labor and Employment, University of California, Berkeley ([email protected]). The author is grateful for funding from the Ford Foundation. Center on Wage and Employment Dynamics Should New York State Eliminate its Subminimum Wage? 1 Introduction Low-wage workers and their supporters in New York received good news when the state enacted a new minimum wage bill in 2016. Minimums for New York City and the counties of Long Island and Westchester are now slated to be $15—and will be phased in by 2022 at the latest. The balance of New York State has annual increases scheduled for a final phase-in to $12.50 on the last day of 2020.1 Until rather recently, minimum wage policy and debate often left out the subminimum wage workforce that relies on tips as part of their wage.2 In 2016, New York could have joined the ranks of the seven states that do not allow tipped workers to be paid a sub-wage, but wound up leaving them out of the new policy. In late 2017, however, Governor Cuomo unveiled a proposal to examine how economic justice would be strengthened if the state eliminated the subminimum wage (also known as the tipped minimum wage).3 As a result, the NYS Department of Labor has scheduled public hearings across the state beginning in spring 2018. -

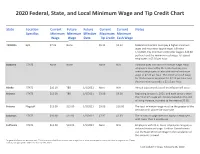

2020 Federal, State, and Local Minimum Wage and Tip Credit Chart

2020 Federal, State, and Local Minimum Wage and Tip Credit Chart State Location Current Future Future Current Current Notes Specifics Minimum Minimum Effective Maximum Minimum Wage Wage Date Tip Credit Cash Wage FEDERAL N/A $7.25 None $5.12 $2.13 Federal contractors must pay a higher minimum wage and respective tipped wage. Effective 1/1/2020, this minimum contractor wage is $10.80 per hour and the minimum cash wage for tipped employees is $7.55 per hour. Alabama STATE None None None N/A Alabama does not have a minimum wage. Most employers covered by the FLSA must pay non- exempt employees at least the federal minimum wage of $7.25 per hour. The minimum cash wage for FLSA-covered employers is $2.13 per hour and the maximum tip credit is $5.12 per hour. Alaska STATE $10.19 TBD 1/1/2021 None N/A Annual adjustments based on inflation will occur. Arizona STATE $12.00 TBD 1/1/2021 $3.00 $9.00 Beginning January 1, 2021, and each January after, the minimum wage will increase based on the cost of living increase, rounded to the nearest $0.05. Arizona Flagstaff $13.00 $15.00 1/1/2021 $3.00 $10.00 The local minimum wage must be the greater of the set rate or $2 above the state rate. Arkansas STATE $10.00 $11.00 1/1/2021 $7.37 $2.63 The minimum wage does not apply to employers with fewer than 4 employees. California STATE $13.00 $14.00 1/1/2021 None N/A Employers with 25 or fewer employees may pay a reduced minimum wage. -

Reviving the Federal Crime of Gratuities

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Law Faculty Scholarly Articles Law Faculty Publications 2013 Reviving the Federal Crime of Gratuities Sarah N. Welling University of Kentucky College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/law_facpub Part of the Criminal Law Commons, and the Legislation Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Sarah Welling, Reviving the Federal Crime of Gratuities, 55 Ariz. L. Rev. 417 (2013). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Faculty Publications at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Scholarly Articles by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reviving the Federal Crime of Gratuities Notes/Citation Information Arizona Law Review, Vol. 55, No. 2 (2013), pp. 417-464 This article is available at UKnowledge: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/law_facpub/275 REVIVING THE FEDERAL CRIME OF GRATUITIES Sarah N. Welling* The federal crime of gratuities prohibits people from giving gifts to federal public officials if the gift is tied to an official act. Both the donor and the donee are liable. The gratuities crime is dysfunctional in two main ways. It is overinclusive in that it covers conduct indistinguishable from bribery. It is underinclusive in that it does not cover conduct that is clearly dangerous: gifts to public officials because of their positions that are not tied to a particular official act. This Article argues that Congress should extend the crime of gratuities to cover gifts because of an official’s position rather than leaving the crime to cover only gifts because of particular official acts. -

Redundancies Companion Chart

This resource is provided as companion content to our podcast Global Solutions: Episode 7 and the information is current as of August 5, 2020. The global situation with regard to the COVID-19 pandemic is developing very rapidly. Employers may want to monitor applicable public health authority guidance and Ogletree Deakins’ Coronavirus (COVID-19) Resource Center for the latest developments. Redundancies in the Age of COVID-19—Quick Reference Country Minimum Statutory Special issuesii Different for Employee Advance COVID-19- Risk Level (*, notice? termination Collective consultation? government related **, ***) payments?i dismissals?iii notice? restrictions? Argentina 15 days – Severance: 1 Union, Yes Yes Yes (collective Generally *** 2 months month per COVID-19 (collective) – when the prohibited / year of prohibitions business crisis double service; 1 preventive severance month when procedure no notice applies). provided. Australia 1-5 weeks (or Redundancy Modern Yes Yes Yes If receiving * pay in lieu of pay: 4-12 award, (collective) subsidy notice) weeks employment contract, Long-service enterprise leave / annual agreement leave Belgium 1-18 weeks Dismissal Union, works Yes Yes Yes None ** bonus; council (collective) (collective) “redundancy allowance” 1 This resource is provided as companion content to our podcast Global Solutions: Episode 7 and the information is current as of August 5, 2020. The global situation with regard to the COVID-19 pandemic is developing very rapidly. Employers may want to monitor applicable public health authority -

New Jersey: 4Th State to Adopt $15 Minimum Wage

th New Jersey: 4 State to Adopt $15 Volume 42 Minimum Wage Issue 14 February 12, 2019 On February 4, New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy signed a bill into law that will gradually increase the minimum wage for Authors most employees working in the state to $15 an hour by 2024. Nancy Vary, JD Employers with at least six employees will have to adjust their Abe Dubin, JD payroll systems and pay practices to ensure compliance with the first rate increase on July 1. Background In 2013, New Jersey voters approved a constitutional amendment to raise the state minimum wage from $7.25 — the federal minimum wage rate — to $8.25 an hour in 2014, and to add automatic cost- of-living increases each year based on the consumer price index for urban wage earners and clerical workers (CPI-W). Since then, efforts to further increase the minimum wage have continued but have been unsuccessful. In 2016, then Gov. Chris Christie vetoed a bill that would have raised New Jersey's minimum wage to $10.10 an hour in 2017 and to at least $15 an hour over the following five years. While many in the business community have expressed concern that rate hikes would hit companies’ bottom lines, increase job loss, and lead to more automation, lawmakers in a number of states are considering raising the minimum wage. For example, last month bills to raise the minimum wage to $15 an hour were introduced in Hawaii, New Mexico, and Maryland. On February 5, the Democratic- controlled Illinois Senate approved increasing the state's $8.25 hourly minimum wage to $15 over six years. -

Albania Growing out of Poverty

ReportNo. 15698-ALB Albania Growing Out of Poverty May 30, 1997 Human ResourcesOperations Division Country Department II Europe and Central Asia Region Documentof the World Bank I. I I 1. II I I .1 I lI II , I 'I I1' ro 1, 1 II 11 I I I|1,,, . ,I,,,II I .I , I ,,1 I , IJ ' I Currency Unit: Albania - Lek Average Exchange Rates (Lek per US$1): 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 8.0 14.4 75.0 102.1 94.7 93.3 104.5 Fiscal Year: January 1 - December 31 List of Acronyms and Abbreviations: ADF Albanian Development Fund CMEA Council For Mutual Economic Assistance GDP Gross Domestic Product IMR Infant Mortality Rate MOLSP Ministry of Labor and Social Policy PIP Public Investment Program INSTAT Albanian Institute for Statistics Acknowledgements This report was managed and written by Christine Allison (Senior Economist). The team that prepared the materials for the report included Robert Christiansen, Yvonne Ying and Sasoun Tsirounian (rural poverty), Janis Bernstein, Helen Garcia and Bulent Ozbilgin (urban poverty), Helena Tang (macroeconomic background), Melitta Jakab (demographics and health), Helen Shariari (gender issues), and Harold Alderman (food security and social assistance). Background studies were prepared by Rachel Wheeler (land issues), Ahmet Mancellari (labor market), Nora Dudwick (qualitative survey), Dennis Herschbach (historical overview) and UNICEF (education). Peter Szivos provided techncial assistance to INSTAT. A number of people provided invaluable assistance in Albania: Peter Schumanin and Sokol Kondi (UNDP), Gianfranco Rotigliano and Bertrand Bainvel (UNICEF). Mimoza and Nesti Dhamo (urban surveys) and the staff of the resident mission. -

Alabama Minimum Wage Laws

Alabama minimum wage laws Localities with minimum wage different than state minimum wage City with different minimum wage ■ County with different minimum wage State minimum wage laws Minimum wage None - Federal minimum wage of $7.25 applies Tipped wage None - Federal tipped wage of $2.13 applies Most recent increase n/a Most recent major change n/a to minimum wage law Upcoming increases n/a Indexing n/a Notes n/a Alaska minimum wage laws Localities with minimum wage different than state minimum wage City with different minimum wage ■ County with different minimum wage State minimum wage laws Minimum wage $10.19 Tipped wage $10.19 Most recent increase $9.89 to $10.19, effective January 1, 2020 Most recent major change 2014, by ballot measure to minimum wage law Upcoming increases Annual indexing effective January 1 Indexing Annual increases based on the percentage change in the CPI-U for the Anchorage metropolitan area. Notes n/a Arizona minimum wage laws Localities with minimum wage different than state minimum wage City with different minimum wage ■ County with different minimum wage State minimum wage laws Minimum wage $12.00 Tipped wage $9.00 Most recent increase $11.00 to $12.00, effective January 1, 2020 Most recent major change 2016, by ballot measure to minimum wage law Upcoming increases Annual indexing beginning January 1, 2021 Indexing Annual increases based on the percentage change in the Consumer Price Index for Urban Wage Earners and Clerical Workers (CPI-W), U.S. city average Notes n/a Flagstaff $13.00 minimum wage, $10.00 -

Estimating the Impact of a $15.00 Minimum Wage in Florida

September 2020 Estimating the Impact of a $15.00 Minimum Wage in Florida Technical Analysis By: Dr. William Even, Miami University Dr. David Macpherson, Trinity University Prepared with support from Save Florida Jobs, Inc. The economists retained sole control over their technical analysis. About the Economists DR. DAVID MACPHERSON is the E.M. Stevens Professor of Economics at Trinity University, where he also serves as department chair. Prior to joining Trinity University, he held the Rod and Hope Brim Eminent Scholar Chair in Economics, and was Director of the Pepper Institute on Aging and Public Policy at Florida State University. Earlier, he served as an assistant and associate professor of economics at Miami University. Macpherson’s research has been concentrated on examining factors that cause deviations from wage equalization. In particular, he has focused on the role of trade unions, pensions, wage discrimination, industry deregulation, and the minimum wage. Macpherson has written over 60 journal articles and book chapters. He is a co-author of the undergraduate textbooks Economics: Private and Public Choice and Contemporary Labor Economics. He also co-authored the book Pensions and Productivity. With Barry Hirsch, he provides union data to researchers and the public through the web site www.unionstats.com. DR. WILLIAM EVEN is a Professor of Economics in the Farmer School of Business at Miami University. He received his Ph.D. in economics from the University of Iowa in 1984. He is a research fellow with the Scripps Gerontology Center, the Employee Benefits Research Institute and the Institute for the Study of Labor. His recent research examines the effects of minimum wage laws, the Affordable Care Act, the effect of Greek affiliation on academic performance, and the relationship between skills and earnings among older workers. -

2021 Minimum Wage Increases Upd

The following states and municipalities will raise the minimum wage in 2021. NOTES & FUTURE STATE OR MINIMUM WAGE MAXIMUM MINIMUM SCHEDULED LOCALITY RATE TIP CREDIT TIPPED WAGE INCREASES FEDERAL $7.25 $5.12 $2.13 Tipped employees must MINIMUM regularly earn at least $30 per month in tips. FEDERAL $10.95 $3.30 $7.65 CONTRACTORS Alabama $7.25* Federal law applies Federal law applies Alaska $10.34 Tip credit prohibited Tip credit prohibited Arizona $12.15 $3.00 $9.15 Flagstaff $15.00 ** ** Arkansas $11.00 $8.37 $2.63 Tipped employees must regularly earn at least $20 per month in tips. California $14.00 for businesses with Tip credit prohibited Tip credit prohibited 26 employees or more; $13.00 for businesses with fewer than 26 employees Alameda $15.00 ** ** Belmont $15.90 ** ** Berkeley $16.07 ** ** Burlingame $15.00 Cupertino $15.65 ** ** Daly City $15.00 ** ** El Cerrito $15.61 ** ** Emeryville $16.84 ** ** $13.50 for small employers ** ** Increasing to $15 for (25 or fewer employees); Fremont small employers $15.00 for large employers effective 07/01/21. (26 or more employees) ** ** Half Moon Bay $15.00 $15.00 for businesses with ** ** 26 employees or more; Hayward $14.00 for businesses with fewer than 26 employees Client Alert: 2021 Minimum Wage Increases Upd. Dec. 2020 NOTES & FUTURE STATE OR MINIMUM WAGE MAXIMUM MINIMUM SCHEDULED LOCALITY RATE TIP CREDIT TIPPED WAGE INCREASES $15.47 for hourly hotel ** ** workers; Long Beach . $15.30 for hourly concessionaire workers Los Altos $15.65 ** ** $15.00 for businesses with ** ** 26 or more employees; $14.25 for businesses with 25 or fewer employees or Increasing to $15 for Los Angeles City and non-profit corporations with businesses with 25 or County 26 or more employees with fewer employees approval to pay a deferred effective 07/01/21. -

Employment & Labour

Employment & Labour Law 2019 Seventh Edition Contributing Editor: Charles Wynn-Evans Global Legal Insights Employment & Labour Law 2019, Seventh Edition Contributing Editor: Charles Wynn-Evans Published by Global Legal Group GLOBAL LEGAL INSIGHTS – EMPLOYMENT & LABOUR LAW 2019, SEVENTH EDITION Contributing Editor Charles Wynn-Evans, Dechert LLP Editor Sam Friend Senior Editors Caroline Collingwood & Rachel Williams Group Consulting Editor Alan Falach Publisher Rory Smith We are extremely grateful for all contributions to this edition. Special thanks are reserved for Charles Wynn-Evans for all of his assistance. Published by Global Legal Group Ltd. 59 Tanner Street, London SE1 3PL, United Kingdom Tel: +44 207 367 0720 / URL: www.glgroup.co.uk Copyright © 2018 Global Legal Group Ltd. All rights reserved No photocopying ISBN 978-1-912509-49-2 ISSN 2050-2117 This publication is for general information purposes only. It does not purport to provide comprehensive full legal or other advice. Global Legal Group Ltd. and the contributors accept no responsibility for losses that may arise from reliance upon information contained in this publication. This publication is intended to give an indication of legal issues upon which you may need advice. Full legal advice should be taken from a qualified professional when dealing with specific situations. The information contained herein is accurate as of the date of publication. Printed and bound by TJ International, Trecerus Industrial Estate, Padstow, Cornwall, PL28 8RW December 2018 CONTENTS Preface -

Greco Eval III Rep 2008 9E FINAL Denmark ETS173 PUBLIC

DIRECTORATE GENERAL OF HUMAN RIGHTS AND LEGAL AFFAIRS DIRECTORATE OF MONITORING Strasbourg, 2 July 2009 Public Greco Eval III Rep (2008) 9E Theme I Third Evaluation Round Evaluation Report on Denmark on Incriminations (ETS 173 and 191, GPC 2) (Theme I) Adopted by GRECO at its 43 rd Plenary Meeting (Strasbourg, 29 June – 2 July 2009) Secrétariat du GRECO GRECO Secretariat www.coe.int/greco Conseil de l’Europe Council of Europe F-67075 Strasbourg Cedex +33 3 88 41 20 00 Fax +33 3 88 41 39 55 I. INTRODUCTION 1. Denmark joined GRECO in 2000. GRECO adopted the First Round Evaluation Report (Greco Eval I Rep (2002) 6E Final) in respect of Denmark at its 10 th Plenary Meeting (8-12 July 2002) and the Second Round Evaluation Report (Greco Eval II Rep (2004) 6E) at its 22 nd Plenary Meeting (14-18 March 2005). The afore-mentioned Evaluation Reports, as well as their corresponding Compliance Reports, are available on GRECO’s homepage (http://www.coe.int/greco ). 2. GRECO’s current Third Evaluation Round (launched on 1 January 2007) deals with the following themes: - Theme I – Incriminations: Articles 1a and 1b, 2-12, 15-17, 19 paragraph 1 of the Criminal Law Convention on Corruption (ETS 173), Articles 1-6 of its Additional Protocol (ETS 191) and Guiding Principle 2 (criminalisation of corruption). - Theme II – Transparency of Party Funding: Articles 8, 11, 12, 13b, 14 and 16 of Recommendation Rec(2003)4 on Common Rules against Corruption in the Funding of Political Parties and Electoral Campaigns, and - more generally - Guiding Principle 15 (financing of political parties and election campaigns). -

Restaurants Flourish with One Fair Wage

BETTER WAGES, BETTER TIPS Restaurants Flourish with One Fair Wage FEBRUARY 13, 2018 BY RESTAURANT OPPORTUNITIES CENTERS UNITED BETTER WAGES, BETTER TIPS: Restaurants Flourish with One Fair Wage THERE ARE SIX MILLION TIPPED WORKERS ACROSS THE NATION, the vast majority women and disproportionately workers of color.1 Under federal law these workers can be paid as little as $2.13 an hour, with the remainder of their income derived solely from tips. As a result, tipped workers live in poverty and depend on food stamps at rates twice that of the general population.2 Since 1996, when the tipped subminimum wage was frozen at $2.13, workers have been abandoned by federal wage policy. Seven states have adopted equal treatment for tipped workers ensuring all workers one fair wage, independent of tips. In those seven states: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY EXECUTIVE • Sexual harassment is lower than in the subminimum wage states that maintain an unequal treatment regime. Tipped women workers who earn a guaranteed wage report half the rate of sexual harassment as women in states with a $2.13 minimum wage since they do not have to accept inappropri- ate behavior from customers to guarantee an income (Figure A). Tipped women FIGURE A workers in $2.13 states report that they are three times more likely to be told by INCIDENCE OF SEXUAL HARASSMENT management to alter their appearance and to wear ‘sexier,’ more revealing clothing BY WAGE REGION (±2*SE) than women in equal treatment states.3 Workers in equal treatment (OFW) states experience half the rate of total sexual • Wages including tips are unambiguously higher than in the 43 harassment, compared to workers in unequal states that maintain an unequal treatment regime.