When the Artist Is Alive in Any Person, Whatever His Kind of Work May Be, He Becomes an Inventive, Searching, Daring, Self-Expressing Creature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fro F M V M°J° Nixon Is Mojo Is in A

TW O G R EA T W H A T'S FILMS FROMI HAPPENING S O U TH T O VIC AFR ICA DUNLO P 9A 11A The Arts and Entertainment Section of the Daily Nexus OF NOTE THIS WEEK 1 1 « Saturday: Don Henley at the Santa Barbara County Bowl. 7 p.m. Sunday: The Jefferson Airplane re turns. S.B. County Bowl, 3 p.m. Tuesday: kd. long and the reclines, country music from Canada. 8 p.m. at the Ventura Theatre Wednesday: Eek-A-M ouse deliv ers fun reggae to the Pub. 8 p.m. Definately worth blowing off Countdown for. Tonight: "Gone With The Wind," The Classic is back at Campbell Hall, 7 p.m. Tickets: $3 w/student ID 961-2080 Tomorrow: The Second Animation -in n i Celebration, at the Victoria St. mmm Theatre until Oct. 8. Saturday: The Flight of the Eagle at Campbell Hall, 8 p.m. H i « » «MI HBfi MIRiM • ». frOf M v M°j° Nixon is Mojo is in a College of Creative Studies' Art vJVl 1T1.J the man your band with his Gallery: Thomas Nozkowski' paint ings. Ends Oct. 28. University Art Museum: The Tt l t f \ T/'\parents prayed partner, Skid Other Side of the Moon: the W orldof Adolf Wolfli until Nov. 5; Free. J y l U J \ J y ou'd never Roper, who Phone: 961-2951 Women's Center Gallery: Recent Works by Stephania Serena. Large grow up to be. plays the wash- color photgraphs that you must see to believe; Free. -

Trinity Sunday, Year A

Trinity Sunday, Year A Reading Difficult Texts with the God of Love and Peace We all read Bible passages in the light of our own experiences, concerns and locations in society. It is not surprising that interpretations of the Bible which seem life-giving to some readers will be experienced by other readers as harmful or oppressive. What about these passages that are used to speak of the concept of the Trinity? This week's lectionary Bible passages: Genesis 1:1-2:4a; Psalm 8; 2 Corinthians 13:11-13; Matthew 28:16-20 Who's in the Conversation A conversation among the following scholars and pastors “Despite the desire of some Christians to marginalize those who are different, our faith calls us to embrace the diversity of our personhood created by God and celebrate it.” Bentley de Bardelaben “People often are unable to see „the goodness of all creation‟ because of our narrow view of what it means to be human and our doctrines of sin, God and humanity." Valerie Bridgeman Davis “By affirming that we, too, are part of God‟s „good creation,‟ lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people of faith begin to take responsibility for fostering love and peace throughout creation." Ken Stone “When we creep in the direction of believing that we absolutely know God, Christ, and the Holy Spirit, we have not only limited the Trinity, but also sown the seeds of hostility and elitism. We need to be reminded of the powerful, mysterious and surprising ways that the Trinity continues to work among all creation." Holly Toensing What's Out in the Conversation A conversation about this week's lectionary Bible passages LGBT people know that Scripture can be used for troubling purposes. -

The Archaeology of Time Travel Represents a Particularly Significant Way to Bring Experiencing the Past the Past Back to Life in the Present

This volume explores the relevance of time travel as a characteristic contemporary way to approach (Eds) & Holtorf Petersson the past. If reality is defined as the sum of human experiences and social practices, all reality is partly virtual, and all experienced and practised time travel is real. In that sense, time travel experiences are not necessarily purely imaginary. Time travel experiences and associated social practices have become ubiquitous and popular, increasingly Chapter 9 replacing more knowledge-orientated and critical The Archaeology approaches to the past. The papers in this book Waterworld explore various types and methods of time travel of Time Travel and seek to prove that time travel is a legitimate Bodil Petersson and timely object of study and critique because it The Archaeology of Time Travel The Archaeology represents a particularly significant way to bring Experiencing the Past the past back to life in the present. in the 21st Century Archaeopress Edited by Archaeopress Archaeology www.archaeopress.com Bodil Petersson Cornelius Holtorf Open Access Papers Cover.indd 1 24/05/2017 10:17:26 The Archaeology of Time Travel Experiencing the Past in the 21st Century Edited by Bodil Petersson Cornelius Holtorf Archaeopress Archaeology Archaeopress Publishing Ltd Gordon House 276 Banbury Road Oxford OX2 7ED www.archaeopress.com ISBN 978 1 78491 500 1 ISBN 978 1 78491 501 8 (e-Pdf) © Archaeopress and the individual authors 2017 Economic support for publishing this book has been received from The Krapperup Foundation The Hainska Foundation Cover illustrations are taken from the different texts of the book. See List of Figures for information. -

Read an Excerpt

The Artist Alive: Explorations in Music, Art & Theology, by Christopher Pramuk (Winona, MN: Anselm Academic, 2019). Copyright © 2019 by Christopher Pramuk. All rights reserved. www.anselmacademic.org. Introduction Seeds of Awareness This book is inspired by an undergraduate course called “Music, Art, and Theology,” one of the most popular classes I teach and probably the course I’ve most enjoyed teaching. The reasons for this may be as straightforward as they are worthy of lament. In an era when study of the arts has become a practical afterthought, a “luxury” squeezed out of tight education budgets and shrinking liberal arts curricula, people intuitively yearn for spaces where they can explore together the landscape of the human heart opened up by music and, more generally, the arts. All kinds of people are attracted to the arts, but I have found that young adults especially, seeking something deeper and more worthy of their questions than what they find in highly quantitative and STEM-oriented curricula, are drawn into the horizon of the ineffable where the arts take us. Across some twenty-five years in the classroom, over and over again it has been my experience that young people of diverse religious, racial, and economic backgrounds, when given the opportunity, are eager to plumb the wellsprings of spirit where art commingles with the divine-human drama of faith. From my childhood to the present day, my own spirituality1 or way of being in the world has been profoundly shaped by music, not least its capacity to carry me beyond myself and into communion with the mysterious, transcendent dimension of reality. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. ProQuest Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI 1 J93S. I hereby recommend that the thesis prepared under my supervision bu ___________________ entitled TVip Aphorisms of GeoTg Christoph Lichtenberg _______ with a Brief Life of Their Author. Materials for a _______ Biography of Lichtenberg. ______________________________________ be accepted as fulfilling this part of the requirements for the degree o f (p /fc -£^OQOTj o Approved by: <r , 6 ^ ^ FORM 660—G.S. ANO CO.—lM—7«33 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

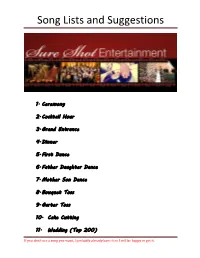

Song Lists and Suggestions

Song Lists and Suggestions 1. Ceremony 2. Cocktail Hour 3. Grand Entrance 4. Dinner 5. First Dance 6. Father Daughter Dance 7. Mother Son Dance 8. Bouquet Toss 9. Garter Toss 10. Cake Cutting 11. Wedding (Top 200) If you don’t see a song you want, I probably already have it or I will be happy to get it. Page 1 of 1 Ceremony CD 20 songs, 1.2 hours, 133.9 MB Name Time Album Artist 1 All of Me (In the Style of John Lege… 4:38 Modern Acoustic Music for Beautif… Acoustic Guitar Guy 2 At Last (String Quartet Tribute to E… 2:40 The Gay Wedding Collection Vitamin String Quartet 3 Bittersweet Symphony 3:40 Symphonic Rock Royal Philharmonic Orchestra 4 Bridal March 1:48 For a Lifetime Jonathan Cain 5 Can't Help Falling in Love 2:54 Can't Help Falling in Love - Single Haley Reinhart 6 Can't Help Falling In Love 4:32 Vitamin String Quartet Tribute to M… Vitamin String Quartet 7 Canon in D 5:24 Wedding Music: Instrumental Song… Wedding Music Experts: The O'Nei… 8 The Cello Song 3:17 The Piano Guys The Piano Guys 9 From This Moment On 4:34 Wedding Music: Instrumental Song… Wedding Music Experts: The O'Nei… 10 Here Comes the Sun 3:20 Instrumental Songs - Soft Rock Gu… Instrumental Songs Music 11 In My Life 2:27 In My Life - A Piano Tribute to the… TJR 12 Just The Way You Are 4:22 The Piano Guys 2 The Piano Guys 13 Just the Way You Are 3:14 The Modern Wedding Collection, V… Vitamin String Quartet 14 Latch (Acoustic) 3:41 Nirvana Sam Smith 15 Marry Me 3:25 Save Me, San Francisco (Bonus Tr… Train 16 Over The Rainbow, Simple Gifts 3:44 The Piano Guys The -

De Classic Album Collection

DE CLASSIC ALBUM COLLECTION EDITIE 2013 Album 1 U2 ‐ The Joshua Tree 2 Michael Jackson ‐ Thriller 3 Dire Straits ‐ Brothers in arms 4 Bruce Springsteen ‐ Born in the USA 5 Fleetwood Mac ‐ Rumours 6 Bryan Adams ‐ Reckless 7 Pink Floyd ‐ Dark side of the moon 8 Eagles ‐ Hotel California 9 Adele ‐ 21 10 Beatles ‐ Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band 11 Prince ‐ Purple Rain 12 Paul Simon ‐ Graceland 13 Meat Loaf ‐ Bat out of hell 14 Coldplay ‐ A rush of blood to the head 15 U2 ‐ The unforgetable Fire 16 Queen ‐ A night at the opera 17 Madonna ‐ Like a prayer 18 Simple Minds ‐ New gold dream (81‐82‐83‐84) 19 Pink Floyd ‐ The wall 20 R.E.M. ‐ Automatic for the people 21 Rolling Stones ‐ Beggar's Banquet 22 Michael Jackson ‐ Bad 23 Police ‐ Outlandos d'Amour 24 Tina Turner ‐ Private dancer 25 Beatles ‐ Beatles (White album) 26 David Bowie ‐ Let's dance 27 Simply Red ‐ Picture Book 28 Nirvana ‐ Nevermind 29 Simon & Garfunkel ‐ Bridge over troubled water 30 Beach Boys ‐ Pet Sounds 31 George Michael ‐ Faith 32 Phil Collins ‐ Face Value 33 Bruce Springsteen ‐ Born to run 34 Fleetwood Mac ‐ Tango in the night 35 Prince ‐ Sign O'the times 36 Lou Reed ‐ Transformer 37 Simple Minds ‐ Once upon a time 38 U2 ‐ Achtung baby 39 Doors ‐ Doors 40 Clouseau ‐ Oker 41 Bruce Springsteen ‐ The River 42 Queen ‐ News of the world 43 Sting ‐ Nothing like the sun 44 Guns N Roses ‐ Appetite for destruction 45 David Bowie ‐ Heroes 46 Eurythmics ‐ Sweet dreams 47 Oasis ‐ What's the story morning glory 48 Dire Straits ‐ Love over gold 49 Stevie Wonder ‐ Songs in the key of life 50 Roxy Music ‐ Avalon 51 Lionel Richie ‐ Can't Slow Down 52 Supertramp ‐ Breakfast in America 53 Talking Heads ‐ Stop making sense (live) 54 Amy Winehouse ‐ Back to black 55 John Lennon ‐ Imagine 56 Whitney Houston ‐ Whitney 57 Elton John ‐ Goodbye Yellow Brick Road 58 Bon Jovi ‐ Slippery when wet 59 Neil Young ‐ Harvest 60 R.E.M. -

The Social Impact of the Revolution

THE SOCIAL IMPACT OF THE REVOLUTION AMERICAN ENTERPRISE INSTITUTE'S DISTINGUISHED LECTURE SERIES Robert Nisbet, historical sociologist and intellectual historian, is Albert Schweitzer professor-elect o[ the humanities at Columbia University. ROBERTA. NISBET THE SOCIAL IMPACT OF THE REVOLUTION Distinguished Lecture Series on the Bicentennial This lecture is one in a series sponsored by the American Enterprise Institute in celebration of the Bicentennial of the United States. The views expressed are those of the lecturers and do not necessarily reflect the views of the staff,officers or trustees of AEI. All of the lectures in this series will be collected later in a single volume. revolution · continuity · promise ROBERTA. NISBET THE SOCIAL IMPACT OF THE REVOLUTION Delivered in Gaston Hall, Georgetown University, Washington, D.C. on December 13, 1973 American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research Washington, D.C. © 1974 by American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, Washington, D.C. ISBN 0-8447-1303-1 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number L.C. 74-77313 Printed in the United States of America as there in fact an American Revolution at the end of the eighteenth century? I mean a revolu tion involving sudden, decisive, and irreversible changes in social institutions, groups, and traditions, in addition to the war of libera tion from England that we are more likely to celebrate. Clearly, this is a question that generates much controversy. There are scholars whose answer to the question is strongly nega tive, and others whose affirmativeanswer is equally strong. Indeed, ever since Edmund Burke's time there have been students to de clare that revolution in any precise sense of the word did not take place-that in substance the American Revolution was no more than a group of Englishmen fighting on distant shores for tradi tionally English political rights against a government that had sought to exploit and tyrannize. -

Download Europe Full Album the Final Countdown (Expanded Edition) Purchase and Download This Album in a Wide Variety of Formats Depending on Your Needs

download europe full album The Final Countdown (Expanded Edition) Purchase and download this album in a wide variety of formats depending on your needs. Buy the album Starting at £10.49. One of the most glorious launches in history, the title track for the thrice-platinum The Final Countdown is so bombastically brilliant, such glorious garbage, that this nuclear hair assault could only spew from the vacuous '80s. But the full-tilt follow-up "Rock the Night" rules also: "You know it ain't easy/Running out of thrills." "Carrie" comes off a consummate butane ballad. Meanwhile, the rest of the disc packs so much power that Swedish superheroes Europe get away with all the processed pretension. In fact, the lofty ambition of "Danger on the Track," "Ninja," and "Cherokee" (each as tasty as its title) combines with heated drive and hot delivery to meld The Final Countdown into a unique portrait of propulsive prog and a worthy addition to any hard rock collection. This is the story; this is the legend told by Teutonic guitars and predictable keyboards ringing pure and hurtling through each and every convention perfectly. The quintet's big-boy Epic inaugural, The Final Countdown deftly combines the Valhalla victory of Europe's heroic debut with the American poodle pomposity that devoured the band. You could live without The Final Countdown, but why? © Doug Stone /TiVo. Europe (2) Hair / Glam Metal (Heavy Metal) band from Upplands Väsby, Stockholm, (Sweden). Europe formed in 1979. The band rose to international fame in the 1980s with its third album, 1986's The Final Countdown, which sold over three million copies in the United States. -

The Other Side V O L U M E X X I V

N 0 V E M n E R 2 , I 9 9 4 The Other Side V o L u M E X X I V . I s !i u E 2 Po ectio Fall 1994 .I on 187 Unplugged Oh \veil, \vhatevp; Clip 'n' collect! NICOLE LAMPHERE EXPLORES THE EcocENTER (PG. 8) • PHoro EssAY OF THE O NTARIO YoUTH CENTER (PG. 13) • J uSTIN Roon ON MURALs (PG. 6) THE OTHER SIDE on everywhere, and that the apathetic are just too busy watching TV to figure this oul I am thinking particularly of the forum on Lab?r editor's desk organizing that took place in the Founder's Room on ~to~r 26th_m which representatives from a variety of Southern Cahforn1a orgamz "It was the sad confession, and continual exemplification, of the short-comings of the composite man- the spirit ingcoalitionsspokeon the work they havedone to secure basic rights burthened in clay and working in matter- and of the despair that assails the higher nature, at finding itself so miserably for documented and undocumented workers. There is also a flurry thwarted by the earthly part." -Nathania! Hawthorne, ''The Birth-mark" of activity that Pitzer faculty and students a_re participati_ng such as labor organizing internships and the on-gomg efforts w1th staff on Editors-in-Chief: Kim Gilmore On lazy afternoons in grade school,as the heaters purred softly in the background, the kids in my class laid comfortably campus to elevate working conditions for '1ow-level employees" Heidi Schumnn on the floor, mesmerized during story time by the tale of Harriet Tubman. -

Ttu Stc001 000054.Pdf (11.39Mb)

SOCIAL THEORY THE LIBRARY OF SOCIAL STUDIES Edited by G. D. H. COLE SOCIAL THEORY By G. D. H. COLE, Author of "Self-Government in Industry," " Labour in the Commonwealth," etc. THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION By J. L. and B. E. HAMMOND, Authors of "The Village Labourer," " The Town Labourer," etc. THE INDUSTRIAL HISTORY OP^ MODERN BRITAIN (1830-1919). By J. R. TAVI.OR, Joint-Author of "The Industrial Outlook," etc. THE FALL OF FEUDALISM IN FRANCE By SYDNEY HERBERT, Author of " Modern Europe," etc. THE FRENCH REVOLUTION IN POLITICAL THOUGHT By M. B, RECKITT, Author of "The Meaning of National Guilds," etc. THE BRITISH LABOUR MOVEMENT By C. M. LLOYD, Author of "Trade Unionism," "The Reorganisa tion of Local Government," etc. INDUSTRY IN THE MIDDLE AGES By G. D. H. and M. I. COLE SOCIAL THEORY BY G. D. H. COLE FELLOW OF MAGDALEN COLLEGE, OXFORD AUTHOR OF "SELF-GOVERNMENT IN INDUSTRY" "LABOUR IN THE COMMONWEALTH" ETC. METHUEN & GO. LTD. 36 ESSEX STREET W.G. LONDON First Published in ig20 CONTENTS CHAP. PAGE I. THE FORMS OF SOCIAL THEORY . I IL SOME NAMES AND THEIR MEANING . 25 III. THE PRINCIPLE OF FUNCTION . .47 IV. THE FORMS AND MOTIVES OF ASSOCIATION . 63 V. THE STATE . .81 VI. DEMOCRACY AND REPRESENTATION . 103 VII. GOVERNMENT AND LEGISLATION . .^ 117 VIII. COERCION AND CO-ORDINATION . .128 IX. THE ECONOMIC STRUCTURE OF SOCIETY . 144 X. REGIONALISM AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT . 158 XI. CHURCHES . .172 XII. LIBERTY . .180 XIII. THE ATROPHY OF INSTITUTIONS . 193 XIV. CONCLUSION . .201 INDEX -215 SOCIAL THEORY CHAPTER I THE FORMS OF SOCIAL THEORY. -

TEARS for FEARS CONCERT RESCHEDULED for SEPTEMBER 26 Original Tickets Will Be Honored

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: John VanderHaagen | Public Relations Manager | 616-975-3155 | [email protected] TEARS FOR FEARS CONCERT RESCHEDULED FOR SEPTEMBER 26 Original tickets will be honored. Tickets for rescheduled date go on sale June 24 at 9 a.m. June 17, 2016 — Tears for Fears’ Roland Orzabal and Curt Smith are pleased to announce that they have rescheduled their concert at Frederik Meijer Gardens & Sculpture Park. The concert originally scheduled for June 6 will now take place on Monday, September 26. Tickets purchased for the June 6 concert at Meijer Gardens will be honored for the new date. Refunds will be available at point of purchase until August 1. Please note, after August 1, all tickets for the original June 6 date become non-refundable. Tickets purchased for the September 26 date are non-refundable. Ticket prices are $75 during the members-only presale. After July 1, tickets are $78 for members and $80 for the public. Members-Only Presale Members may buy tickets for the rescheduled date during a members-only presale beginning at 9 a.m., June 24 through midnight, July 1. Members save $5 per ticket during the presale. The preferred method to purchase tickets is online, but multiple options are available: Online at StarTickets.com – handling fee of $8 per order (preferred method) By phone at 1-800-585-3737 - handling fee of $8 per order In-person at Meijer Gardens Admission Desk during normal business hours – no handling fees Public Ticket Sale If tickets remain available after the members-only presale, sales to the public will begin at 9 a.m., July 2.