Treatment of Painful Diabetic Neuropathy—Report of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diabetic Neuropathy: a Position Statement by the American

136 Diabetes Care Volume 40, January 2017 Diabetic Neuropathy: A Position Rodica Pop-Busui,1 Andrew J.M. Boulton,2 Eva L. Feldman,3 Vera Bril,4 Roy Freeman,5 Statement by the American Rayaz A. Malik,6 Jay M. Sosenko,7 and Dan Ziegler8 Diabetes Association Diabetes Care 2017;40:136–154 | DOI: 10.2337/dc16-2042 Diabetic neuropathies are the most prevalent chronic complications of diabetes. This heterogeneous group of conditions affects different parts of the nervous system and presents with diverse clinical manifestations. The early recognition and appropriate man- agement of neuropathy in the patient with diabetes is important for a number of reasons: 1. Diabetic neuropathy is a diagnosis of exclusion. Nondiabetic neuropathies may be present in patients with diabetes and may be treatable by specific measures. 2. A number of treatment options exist for symptomatic diabetic neuropathy. 3. Up to 50% of diabetic peripheral neuropathies may be asymptomatic. If not recognized and if preventive foot care is not implemented, patients are at risk for injuries to their insensate feet. 4. Recognition and treatment of autonomic neuropathy may improve symptoms, POSITION STATEMENT reduce sequelae, and improve quality of life. Among the various forms of diabetic neuropathy, distal symmetric polyneurop- athy (DSPN) and diabetic autonomic neuropathies, particularly cardiovascular au- tonomic neuropathy (CAN), are by far the most studied (1–4). There are several 1 atypical forms of diabetic neuropathy as well (1–4). Patients with prediabetes may Division of Metabolism, Endocrinology & Diabe- – tes, Department of Internal Medicine, University also develop neuropathies that are similar to diabetic neuropathies (5 10). -

Pharmacologic Management of Chronic Neuropathic Pain Review of the Canadian Pain Society Consensus Statement

Clinical Review Pharmacologic management of chronic neuropathic pain Review of the Canadian Pain Society consensus statement Alex Mu MD FRCPC Erica Weinberg MD Dwight E. Moulin MD PhD Hance Clarke MD PhD FRCPC Abstract Objective To provide family physicians with EDITOR’S KEY POINTS a practical clinical summary of the Canadian • Gabapentinoids and tricyclic antidepressants play an important role in Pain Society (CPS) revised consensus first-line management of neuropathic pain (NeP). Evidence published statement on the pharmacologic management since the 2007 Canadian Pain Society consensus statement on treatment of neuropathic pain. of NeP shows that serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors should now also be among the first-line agents. Quality of evidence A multidisciplinary • Tramadol and opioids are considered second-line treatments owing to their interest group within the CPS conducted a increased complexity of follow-up and monitoring, plus their potential for systematic review of the literature on the adverse side effects, medical complications, and abuse. Cannabinoids are current treatments of neuropathic pain in currently recommended as third-line agents, as sufficient-quality studies are drafting the revised consensus statement. currently lacking. Recommended fourth-line treatments include methadone, anticonvulsants with lesser evidence of efficacy (eg, lamotrigine, lacosamide), tapentadol, and botulinum toxin. There is some support for analgesic Main message Gabapentinoids, tricyclic combinations in selected NeP conditions. antidepressants, and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors are the first-line agents • Many of these pharmacologic treatments are off-label for pain or for treating neuropathic pain. Tramadol and on-label for specific pain conditions, and these issues should be clearly other opioids are recommended as second- conveyed and documented. -

NMDA Receptor Antagonists for the Treatment of Neuropathic Pain Compared to Placebo: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Open Journal of Dentistry and Oral Medicine 5(4): 59-71, 2017 http://www.hrpub.org DOI: 10.13189/ojdom.2017.050401 NMDA Receptor Antagonists for the Treatment of Neuropathic Pain Compared to Placebo: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Byron Larsen1, Kristin Mau1, Mariela Padilla2, Reyes Enciso3,* 1Master of Science Program in Orofacial Pain and Oral Medicine, Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry, University of Southern California, USA 2Division of Periodontology, Diagnostic Sciences and Dental Hygiene, Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry, University of Southern California, USA 3Division of Dental Public Health and Pediatric Dentistry, Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry, University of Southern California, USA Copyright©2017 by authors, all rights reserved. Authors agree that this article remains permanently open access under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 International License Abstract The objective of this study is to evaluate the Neuropathic pain has been linked to structural and efficacy of N-Methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor functional somatosensory nervous system alternations that antagonists on neuropathic pain disorders that can occur in produce spontaneous pain and pathologically intensified the orofacial region. These disorders included: Postherpetic reactions to noxious and innocuous stimuli [1]. It is Neuralgia (PHN), Complex Regional Pain Syndrome suggested that different mechanisms are at play regarding (CRPS), Atypical Odontalgia, Temporomandibular Joint orofacial neuropathic pain due to the diverse clinical (TMJ) Arthralgia and facial neuropathies. Materials and manifestations in disorders of various etiologies [2]. More Methods: Three databases (Medline through PubMed, Web specifically, involvement pertains to both peripheral and of Science, and Cochrane library) were searched on January central sensitization mechanisms [3]. -

The Journal of Rheumatology Volume 75, No. Is Fibromyalgia a Neuropathic Pain Syndrome?

The Journal of Rheumatology Volume 75, no. Is fibromyalgia a neuropathic pain syndrome? Michael C Rowbotham J Rheumatol 2005;75;38-40 http://www.jrheum.org/content/75/38 1. Sign up for TOCs and other alerts http://www.jrheum.org/alerts 2. Information on Subscriptions http://jrheum.com/faq 3. Information on permissions/orders of reprints http://jrheum.com/reprints_permissions The Journal of Rheumatology is a monthly international serial edited by Earl D. Silverman featuring research articles on clinical subjects from scientists working in rheumatology and related fields. Downloaded from www.jrheum.org on September 24, 2021 - Published by The Journal of Rheumatology Is Fibromyalgia a Neuropathic Pain Syndrome? MICHAEL C. ROWBOTHAM ABSTRACT. The fibromyalgia syndrome (FM) seems an unlikely candidate for classification as a neuropathic pain. The disorder is diagnosed based on a compatible history and the presence of multiple areas of musculoskeletal tenderness. A consistent pathology in either the peripheral or central nervous system (CNS) has not been demonstrated in patients with FM, and they are not at higher risk for diseases of the CNS such as multiple sclerosis or of the peripheral nervous system such as peripheral neuropathy. A large proportion of FM suf- ferers have accompanying symptoms and signs of uncertain etiology, such as chronic fatigue, sleep distur- bance, and bowel/bladder irritability. With the exception of migraine headaches and possibly irritable bowel syndrome, the accompanying disorders are clearly not neurological in origin. The impetus to classify the FM as a neuropathic pain comes from multiple lines of research suggesting widespread pain and tenderness are associated with chronic sensitization of the CNS. -

Neuropathic Pain (E Eisenberg, Section Editor)

Curr Pain Headache Rep (2017) 21: 28 DOI 10.1007/s11916-017-0629-5 NEUROPATHIC PAIN (E EISENBERG, SECTION EDITOR) Neuropathic Pain: Central vs. Peripheral Mechanisms Kathleen Meacham1,2 & Andrew Shepherd1,2 & Durga P. Mohapatra1,2 & Simon Haroutounian1,2 Published online: 21 April 2017 # Springer Science+Business Media New York 2017 Abstract identify potentially self-sustaining infra-slow CNS oscillatory Purpose of Review Our goal is to examine the processes— activity that may be unique to pNP patients. both central and peripheral—that underlie the development of Summary While new preclinical evidence supports and ex- peripherally-induced neuropathic pain (pNP) and to highlight pands upon the key role of central mechanisms in neuropathic recent evidence for mechanisms contributing to its mainte- pain, clinical evidence for an autonomous central mechanism nance. While many pNP conditions are initiated by damage remains relatively limited. Recent findings from both preclin- to the peripheral nervous system (PNS), their persistence ap- ical and clinical studies recapitulate the critical contribution of pears to rely on maladaptive processes within the central ner- peripheral input to maintenance of neuropathic pain. Further vous system (CNS). The potential existence of an autonomous clinical investigations on the possibility of standalone central pain-generating mechanism in the CNS creates significant im- contributions to pNP may be assisted by a reconsideration of plications for the development of new neuropathic pain treat- the agreed terms or criteria for diagnosing the presence of ments; thus, work towards its resolution is crucial. Here, we central sensitization in humans. seek to identify evidence for PNS and CNS independently generating neuropathic pain signals. -

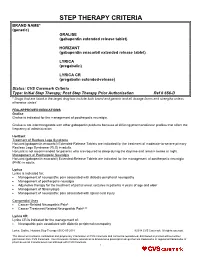

STEP THERAPY CRITERIA BRAND NAME* (Generic) GRALISE (Gabapentin Extended Release Tablet)

STEP THERAPY CRITERIA BRAND NAME* (generic) GRALISE (gabapentin extended release tablet) HORIZANT (gabapentin enacarbil extended release tablet) LYRICA (pregabalin) LYRICA CR (pregabalin extended-release) Status: CVS Caremark Criteria Type: Initial Step Therapy; Post Step Therapy Prior Authorization Ref # 656-D * Drugs that are listed in the target drug box include both brand and generic and all dosage forms and strengths unless otherwise stated FDA-APPROVED INDICATIONS Gralise Gralise is indicated for the management of postherpetic neuralgia. Gralise is not interchangeable with other gabapentin products because of differing pharmacokinetic profiles that affect the frequency of administration. Horizant Treatment of Restless Legs Syndrome Horizant (gabapentin enacarbil) Extended-Release Tablets are indicated for the treatment of moderate-to-severe primary Restless Legs Syndrome (RLS) in adults. Horizant is not recommended for patients who are required to sleep during the daytime and remain awake at night. Management of Postherpetic Neuralgia Horizant (gabapentin enacarbil) Extended-Release Tablets are indicated for the management of postherpetic neuralgia (PHN) in adults. Lyrica Lyrica is indicated for: Management of neuropathic pain associated with diabetic peripheral neuropathy Management of postherpetic neuralgia Adjunctive therapy for the treatment of partial onset seizures in patients 4 years of age and older Management of fibromyalgia Management of neuropathic pain associated with spinal cord injury Compendial Uses Cancer-Related Neuropathic Pain6 Cancer Treatment Related Neuropathic Pain6,12 Lyrica CR Lyrica CR is indicated for the management of: Neuropathic pain associated with diabetic peripheral neuropathy Lyrica, Gralise, Horizant Step Therapy 656-D 05-2018 ©2018 CVS Caremark. All rights reserved. This document contains confidential and proprietary information of CVS Caremark and cannot be reproduced, distributed or printed without written permission from CVS Caremark. -

Pharmacotherapy of Neuropathic Pain: Which Drugs, Which Treatment Algorithms? Nadine Attal*, Didier Bouhassira

Biennial Review of Pain Pharmacotherapy of neuropathic pain: which drugs, which treatment algorithms? Nadine Attal*, Didier Bouhassira Abstract Neuropathic pain (NP) is a significant medical and socioeconomic burden. Epidemiological surveys have indicated that many patients with NP do not receive appropriate treatment for their pain. A number of pharmacological agents have been found to be effective in NP on the basis of randomized controlled trials including, in particular, tricyclic antidepressants, serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor antidepressants, pregabalin, gabapentin, opioids, lidocaine patches, and capsaicin high- concentration patches. Evidence-based recommendations for the pharmacotherapy of NP have recently been updated. However, meta-analyses indicate that only a minority of patients with NP have an adequate response to drug therapy. Several reasons may account for these findings, including a modest efficacy of the active drugs, a high placebo response, the heterogeneity of diagnostic criteria for NP, and an inadequate classification of patients in clinical trials. Improving the current way of conducting clinical trials in NP could contribute to reduce therapeutic failures and may have an impact on future therapeutic algorithms. Keywords: Neuropathic pain, Pharmacotherapy, Clinical trials, Therapeutic algorithms, Phenotypic subgrouping 1. Introduction Here, we briefly present the major pharmacological treatments studied in NP and the latest therapeutic recommendations for Neuropathic pain (NP) is estimated to affect as much as 7% of the general population in European countries19,83 and induces their use. We then outline the difficulties associated with a specific disease burden in patients.6,30,83 It is now considered pharmacotherapy of NP in clinical trials and draw prospects for as a clinical entity regardless of the underlying etiology.4 Epidemi- future drug trials and therapeutic algorithms. -

Usefulness of Antidepressants for Improving the Neuropathic Pain-Like State and Pain-Induced Anxiety Through Actions at Different Brain Sites

Neuropsychopharmacology (2008) 33, 1952–1965 & 2008 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0893-133X/08 $30.00 www.neuropsychopharmacology.org Usefulness of Antidepressants for Improving the Neuropathic Pain-Like State and Pain-Induced Anxiety through Actions at Different Brain Sites 1,2 ,1,2 2 2 2 Kiyomi Matsuzawa-Yanagida , Minoru Narita* , Mayumi Nakajima , Naoko Kuzumaki , Keiichi Niikura , 2 2 2 2 1,2 ,1 Hiroyuki Nozaki , Tomoe Takagi , Eiko Tamai , Nana Hareyama , Mioko Terada , Mitsuaki Yamazaki* ,2 and Tsutomu Suzuki* 1 2 Department of Anesthesiology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Toyama, Toyama, Japan; Department of Toxicology, Hoshi University School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Shinagawa-ku, Tokyo, Japan Clinically, it is well known that chronic pain induces depression, anxiety, and a reduced quality of life. There have been many reports on the relationship between pain and emotion. We previously reported that chronic pain induced anxiety with changes in opioidergic function in the central nervous system. In this study, we evaluated the anxiolytic-like effects of several types of antidepressants under a chronic neuropathic pain-like state and searched for the brain site of action where antidepressants show anxiolytic or antinociceptive effects. Sciatic nerve-ligated mice exhibited thermal hyperalgesia and tactile allodynia from days 7 to 28 after nerve ligation. At 4 weeks after ligation, these mice showed a significant anxiety-related behavior in the light–dark test and the elevated plus–maze test. Under these conditions, repeated administration of antidepressants, including the tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) imipramine, the serotonin noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) milnacipran, and the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) paroxetine, significantly prevented the anxiety-related behaviors induced by chronic neuropathic pain. -

The Voice of the Patient: Neuropathic Pain Associated with Peripheral

The Voice of the Patient A series of reports from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA’s) Patient-Focused Drug Development Initiative Neuropathic Pain Associated with Peripheral Neuropathy Public Meeting: June 10, 2016 Report Date: February 2017 Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Table of Contents Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 3 Meeting overview ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Report overview and key themes ................................................................................................................. 4 Topic 1: Disease Symptoms and Daily Impacts That Matter Most to Patients .............................. 5 Perspectives on most significant symptoms ................................................................................................. 6 Overall impact of neuropathic pain associated with peripheral neuropathy on daily life ........................... 8 Topic 2: Patient Perspectives on Treatments for Neuropathic Pain Associated with Peripheral Neuropathy ............................................................................................................................... 9 Perspectives on current treatments ............................................................................................................. 9 Perspectives -

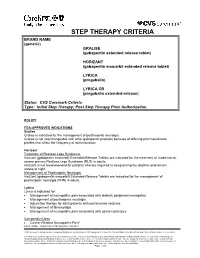

STEP THERAPY CRITERIA BRAND NAME (Generic) GRALISE (Gabapentin Extended Release Tablet)

STEP THERAPY CRITERIA BRAND NAME (generic) GRALISE (gabapentin extended release tablet) HORIZANT (gabapentin enacarbil extended release tablet) LYRICA (pregabalin) LYRICA CR (pregabalin extended-release) Status: CVS Caremark Criteria Type: Initial Step Therapy; Post Step Therapy Prior Authorization POLICY FDA-APPROVED INDICATIONS Gralise Gralise is indicated for the management of postherpetic neuralgia. Gralise is not interchangeable with other gabapentin products because of differing pharmacokinetic profiles that affect the frequency of administration. Horizant Treatment of Restless Legs Syndrome Horizant (gabapentin enacarbil) Extended-Release Tablets are indicated for the treatment of moderate-to- severe primary Restless Legs Syndrome (RLS) in adults. Horizant is not recommended for patients who are required to sleep during the daytime and remain awake at night. Management of Postherpetic Neuralgia Horizant (gabapentin enacarbil) Extended-Release Tablets are indicated for the management of postherpetic neuralgia (PHN) in adults. Lyrica Lyrica is indicated for: • Management of neuropathic pain associated with diabetic peripheral neuropathy • Management of postherpetic neuralgia • Adjunctive therapy for adult patients with partial onset seizures • Management of fibromyalgia • Management of neuropathic pain associated with spinal cord injury Compendial Uses 6 • Cancer-Related Neuropathic Pain Lyrica, Gralise, Horizant Step Therapy Policy 05-2017 CVS Caremark is an independent company that provides pharmacy benefit management services to CareFirst BlueCross BlueShield and CareFirst BlueChoice, Inc. members. CareFirst BlueCross BlueShield is the shared business name of CareFirst of Maryland, Inc. and Group Hospitalization and Medical Services, Inc. CareFirst of Maryland, Inc., Group Hospitalization and Medical Services, Inc., CareFirst BlueChoice, Inc., The Dental Network and First Care, Inc. are independent licensees of the Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association. -

Neuropathic Pain

28 Innovative healthcare, clinics & alternative remedies 9 JANUARY 2021 • NEW YEAR, NEW START DISTRIBUTED WITH THE SATURDAY DAILY MAIL Neuropathic pain Neuropathic pain is a pain condition that can a ect any part of the body Neuropathic pain is the result of injury or damage caused to the sensory nervous system, which is responsible for transmitting pain-related information from the skin and other parts of the body to the spinal cord and brain. Patients often refer to this condi- tion as ‘nerve pain’ and report their symptoms as severe, signif- icantly a ecting their activi- ties of daily living and quality of life. Neuropathic pain varies in nature and intensity and may get better or worse over time. Pain is de ned as chronic or persistent if it outlasts the healing process, which is normally three months. A recent study shows that chronic pain a ects between one-third and one-half of the population of the UK, corresponding to just under 28 million adults1. ere’s an 8-9% estimated prevalence of chronic neuropathic pain. With the increase in life expectancy, NEUROPATHIC PAIN IN HAND SCAR PAIN the rate is anticipated to rise. SHINGLES IN THE NECK CAUSES AND SYMPTOMS MANAGEMENT e International Association which target nerves along the e window of pain relief ere are multiple causes of Persistent pain presents a for the Study of Pain (IASP) spon- pain pathway. Opioids are gener- should be utilised for perfor- neuropathic pain, the most considerable daily challenge sors and promotes the Global ally not recommended because mance of strengthening and common being shingles, with potentially devastating Year Against Pain, a yearlong of the high risks from their long- endurance exercises, improving diabetes mellitus, trapped or e ects on patients. -

Modulation of NMDA Receptor Activity in Fibromyalgia

biomedicines Review Modulation of NMDA Receptor Activity in Fibromyalgia Geoffrey Littlejohn * and Emma Guymer Departments of Medicine, Monash University and Rheumatology, MonashHealth, Melbourne 3168, Australia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +61-03-9594-2575 Academic Editor: Kim Lawson Received: 23 February 2017; Accepted: 7 April 2017; Published: 11 April 2017 Abstract: Activation of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) results in increased sensitivity of spinal cord and brain pathways that process sensory information, particularly those which relate to pain. The NMDAR shows increased activity in fibromyalgia and hence modulation of the NMDAR is a target for therapeutic intervention. A literature review of interventions impacting on the NMDAR shows a number of drugs to be active on the NMDAR mechanism in fibromyalgia patients, with variable clinical effects. Low-dose intravenous ketamine and oral memantine both show clinically useful benefit in fibromyalgia. However, consideration of side-effects, logistics and cost need to be factored into management decisions regarding use of these drugs in this clinical setting. Overall benefits with current NMDAR antagonists appear modest and there is a need for better strategy trials to clarify optimal dose schedules and to delineate potential longer–term adverse events. Further investigation of the role of the NMDAR in fibromyalgia and the effect of other molecules that modulate this receptor appear important to enhance treatment targets in fibromyalgia. Keywords: fibromyalgia; drugs; NMDA receptor; ketamine; memantine 1. Introduction There are multiple pain-related mechanisms that are active in patients with fibromyalgia. The relative contribution of each mechanism appears to vary between patients.