Rindge Dam Removal Position Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

16. Watershed Assets Assessment Report

16. Watershed Assets Assessment Report Jingfen Sheng John P. Wilson Acknowledgements: Financial support for this work was provided by the San Gabriel and Lower Los Angeles Rivers and Mountains Conservancy and the County of Los Angeles, as part of the “Green Visions Plan for 21st Century Southern California” Project. The authors thank Jennifer Wolch for her comments and edits on this report. The authors would also like to thank Frank Simpson for his input on this report. Prepared for: San Gabriel and Lower Los Angeles Rivers and Mountains Conservancy 900 South Fremont Avenue, Alhambra, California 91802-1460 Photography: Cover, left to right: Arroyo Simi within the city of Moorpark (Jaime Sayre/Jingfen Sheng); eastern Calleguas Creek Watershed tributaries, classifi ed by Strahler stream order (Jingfen Sheng); Morris Dam (Jaime Sayre/Jingfen Sheng). All in-text photos are credited to Jaime Sayre/ Jingfen Sheng, with the exceptions of Photo 4.6 (http://www.you-are- here.com/location/la_river.html) and Photo 4.7 (digital-library.csun.edu/ cdm4/browse.php?...). Preferred Citation: Sheng, J. and Wilson, J.P. 2008. The Green Visions Plan for 21st Century Southern California. 16. Watershed Assets Assessment Report. University of Southern California GIS Research Laboratory and Center for Sustainable Cities, Los Angeles, California. This report was printed on recycled paper. The mission of the Green Visions Plan for 21st Century Southern California is to offer a guide to habitat conservation, watershed health and recreational open space for the Los Angeles metropolitan region. The Plan will also provide decision support tools to nurture a living green matrix for southern California. -

Los Angeles County

Steelhead/rainbow trout resources of Los Angeles County Arroyo Sequit Arroyo Sequit consists of about 3.3 stream miles. The arroyo is formed by the confluence of the East and West forks, from where it flows south to enter the Pacific Ocean east of Sequit Point. As part of a survey of 32 southern coastal watersheds, Arroyo Sequit was surveyed in 1979. The O. mykiss sampled were between about two and 6.5 inches in length. The survey report states, “Historically, small steelhead runs have been reported in this area” (DFG 1980). It also recommends, “…future upstream water demands and construction should be reviewed to insure that riparian and aquatic habitats are maintained” (DFG 1980). Arroyo Sequit was surveyed in 1989-1990 as part of a study of six streams originating in the Santa Monta Mountains. The resulting report indicates the presence of steelhead and states, “Low streamflows are presently limiting fish habitat, particularly adult habitat, and potential fish passage problems exist…” (Keegan 1990a, p. 3-4). Staff from DFG surveyed Arroyo Sequit in 1993 and captured O. mykiss, taking scale and fin samples for analysis. The individuals ranged in length between about 7.7 and 11.6 inches (DFG 1993). As reported in a distribution study, a 15-17 inch trout was observed in March 2000 in Arroyo Sequit (Dagit 2005). Staff from NMFS surveyed Arroyo Sequit in 2002 as part of a study of steelhead distribution. An adult steelhead was observed during sampling (NMFS 2002a). Additional documentation of steelhead using the creek between 2000-2007 was provided by Dagit et al. -

Scanned Document

DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY PERMIT Permittee: California Department of Wildlife; Attention: Timothy Chorey Project Name: Regional General Permit No. 78 Reauthorization for the California Department of the Fish and Wildlife Fisheries Restoration Grant Program Permit Number: SPL-2019-00120-CLH Issuing Office: Los Angeles District Note: The term "you" and its derivatives, as used in this permit, means the permittee or any future transferee. The term "this office" refers to the appropriate district or division office of the Corps of Engineers having jurisdiction over the permitted activity or the appropriate official acting under the authority of the commanding officer. You are authorized to perform work in accordance with the terms and conditions specified below. Project Description: To reauthorize the implementation of salmonid habitat enhancement and restoration projects conducted under the California Department of Fish and Wildlife Fisheries Restoration Grant. Program (FRGP) in various coastal streams within Los Angeles District from San Luis Obispo County to San Diego County, California, implemented through the California Department of Fish and Wildlife’s (CDFW) Fisheries Restoration Grant Program (FRGP). Projects would be identified on an annual basis and would apply one or more of the habitat restoration treatments described in the California Salmonid Stream Habitat Restoration Manual (CDFW Manual). Projects may include • In-stream habitat improvements, including cover structures (divide logs, digger logs, spider logs, and log/root wad/boulder combinations), boulder structures (boulder weirs, vortex boulder weirs, boulder clusters, and single- and opposing-boulder wing- deflectors), log structures (log weirs, upsurge weirs, single- and opposing-log wing- deflectors, and Hewitt ramps) and placement of imported spawning gravel may be utilized in certain locations. -

Steelhead/Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus Mykiss) Resources South of the Golden Gate, California

Becker Steelhead/Rainbow Trout Reining (Oncorhynchus mykiss) Steelhead/Rainbow Trout Steelhead/Rainbow Trout Resources South of the Golden Gate, California October 2008 Gordon S. Becker #ENTERFOR%COSYSTEM-ANAGEMENT2ESTORATION Isabelle J. Reining (Oncorhynchus mykiss) Cartography by David A. Asbury Prepared for California State Coastal Conservancy and The Resources Legacy Fund Foundation Resources South of the Golden Gate, California Resources South of the Golden Gate, California The mission of the Center for Ecosystem Management and Restoration is to make effective use of scientific information to promote the restoration and sustainable management of ecosystems. The Center is a not-for-profit corporation, and contributions in support of its programs are tax-deductible. Center for Ecosystem Management & Restoration 4179 Piedmont Ave, Suite 325, Oakland, CA 94611 Center for Ecosystem Management and Restoration 510.420.4565 http://www.cemar.org CEMAR The cover image is a map of the watershed area of streams tributary to the Pacific Ocean south of the Golden Gate, California, by CEMAR. The image above is a 1934 Gazos Creek stream survey report published by the California Division of Fish and Game. Book design by Audrey Kallander. Steelhead/Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) Resources South of the Golden Gate, California Gordon S. Becker Isabelle J. Reining Cartography by David A. Asbury This report should be cited as: Becker, G.S. and I.J. Reining. 2008. Steelhead/rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) resources south of the Golden Gate, California. Cartography by D.A. Asbury. Center for Ecosystem Management and Restoration. Oakland, CA. Center for Ecosystem Management and Restoration TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreward pg. 3 Introduction pg. -

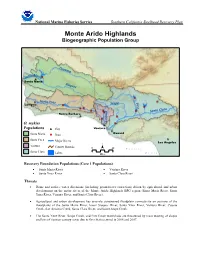

Monte Arido Highlands Biogeographic Population Group

National Marine Fisheries Service Southern California Steelhead Recovery Plan Monte Arido Highlands Biogeographic Population Group o Cuy ama ta Ma San ria Santa Maria Sis quoc San ta Ynez P Sespe i Lompoc r u V a Clara e Sant Santa Barbara n t u r a O. mykiss Populations City Ventura Santa Maria Dam Oxnard Santa Ynez Major Rivers Los Angeles Ventura County Boundary 020Pacific Santa Clara Lakes Ocean Miles Recovery Foundation Populations (Core 1 Populations) • Santa Maria River • Ventura River • Santa Ynez River • Santa Clara River Threats • Dams and surface water diversions (including groundwater extraction) driven by agricultural and urban development on the major rivers of the Monte Arido Highlands BPG region (Santa Maria River, Santa Ynez River, Ventura River, and Santa Clara River). • Agricultural and urban development has severely constrained floodplain connectivity on sections of the floodplains of the Santa Maria River, lower Sisquoc River, Santa Ynez River, Ventura River, Coyote Creek, San Antonio Creek, Santa Clara River, and lower Sespe Creek. • The Santa Ynez River, Sespe Creek, and Piru Creek watersheds are threatened by mass wasting of slopes and loss of riparian canopy cover due to fires that occurred in 2006 and 2007. Santa Maria River Santa Clara River Steelhead – 28 inches Matilija Dam Critical Recovery Actions • Implement operating criteria to ensure the pattern and magnitude of water releases from Bradbury, Gibraltar, Juncal, Twitchell, Casitas, Matilija, Robles Diversion, Vern Freeman Diversion, Santa Felicia, Pyramid, and Castaic dams comport with the natural or pre-dam pattern and magnitude of stream flow in downstream reaches. Physically modify these dams to allow unimpeded volitional migration of steelhead to upstream spawning and rearing habitats. -

Extent of Fishing and Fish Consumption by Fishers in Ventura and Los Angeles County Watersheds in 2005

EXTENT OF FISHING AND FISH CONSUMPTON BY FISHERS IN VENTURA AND LOS ANGELES COUNTY WATERSHEDS IN 2005 M. James Allen Erica T. Jarvis Valerie Raco-Rands Greg Lyon Jesus A. Reyes Dawn M. Petschauer Technical Report 574 - September 2008 EXTENT OF FISHING AND FISH CONSUMPTION BY FISHERS IN VENTURA AND LOS ANGELES COUNTY WATERSHEDS IN 2005 M. James Allen, Erica T. Jarvis, Valerie Raco-Rands, Greg Lyon, Jesus A. Reyes and Dawn M. Petschauer Southern California Coastal Water Research Project 3535 Harbor Blvd., Ste. 110 Costa Mesa, CA 92626 www.sccwrp.org September 15, 2008 Cover Images (Clockwise from the Lower Left): San Gabriel River Estuary, Upper Calleguas Creek (Coastal Terrace Stream), Lake Casitas (Mountain Reservoir), Big Tujunga Creek (Mountain Stream), Peck Road Park Lake (Urban Lake), and Lower San Gabriel River (Coastal Terrace Stream). Technical Report 574 Table of Contents Abstract.............................................................................................................................. vi Introduction......................................................................................................................... 1 Methods............................................................................................................................... 3 Field Survey....................................................................................................................3 Overview of Study ...................................................................................................... 3 Data -

Susan B. Nelson Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8gq7463 No online items Guide to the Susan B. Nelson Collection Special Collections & Archives University Library California State University, Northridge 18111 Nordhoff Street Northridge, CA 91330-8326 URL: https://library.csun.edu/SCA Contact: https://library.csun.edu/SCA/Contact © Copyright 2020 Special Collections & Archives. All rights reserved. Guide to the Susan B. Nelson URB.SBN 1 Collection Contributing Institution: Special Collections & Archives Title: Susan B. Nelson Collection Identifier/Call Number: URB.SBN Extent: 77.88 linear feet Extent: 157.79 Gigabytes Date (inclusive): 1892-2003 Abstract: The Susan B. Nelson Collection documents the professional and personal life of Susan Louise Barr Nelson, an environmental and community planner, and social and political activist. Nelson played a fundamental role in the establishment of the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area, which became the largest urban national park in the United States. The collection also details Nelson's work with numerous groups and organizations to preserve open space and parklands for recreational use and includes materials pertaining to a number of social welfare issues with which she was involved. Additionally, the collection contains Nelson's personal writings and materials related to her family, home life, and education. Language of Material: English Biographical Information: Susan Louise Barr was born in Syracuse, New York on April 13, 1927 to Mr. and Mrs. Winston Barr. The family moved to California in 1930, first settling in a bungalow in Hollywood before moving to the Carthay District Center, which today is known as Carthay Circle, Los Angeles. With 1930's Los Angeles significantly less affected by urban sprawl, Susan spent her childhood playing in the area's parks and the Ballona-Playa del Rey Lagoon's marsh, which resulted in a life-long love of the outdoors and its natural resources. -

DAM REMOVAL Science and Decision Making

SDMS DocID 273439 DAM REMOVAL Science and Decision Making THK HEINZ THE H- JOHN HEINZ III CENTER FOR ChN I 1 R SCIFNCE> ECONOMICS AND THE ENVIRONMENT • Dam /\/ Dammed Rivers /\/ Undammed Rivers Plate I This map of Pennsylvania shows the statewide distribution of dams and major rivers. None of Pennsylvania's major rivers can be considered undammed or unchannelized. The map was compiled using data on 1,400 large and medium- sized dams from the National Inventory of Dams (NID). To be included in the NID, the dam must be either more than 6 ft (2 m) high with more than 50 acre-feet (61,000 cu m) of storage or 25 ft (8 m) high with more than 15 acre-feet (18,500 cu m) of storage. Pennsylvania also has many smaller dams that are not included in the NID and are therefore not represented on this map. (See page 102 for discussion.) Sources: Dam data from U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (2001); National Inventory of Dams (NID) river data from the National Atlas (2001). DAM REMOVAL Science and Decision Making THE THE H> HN HEINZ m CENTER FOR MFTMri±LHN Z7, J°, ECONOMICS AND THE ENVIRONMENT CENTER SCIENCE The H. John Heinz III Center for Science, Economics and the Environment Established in December 1995 in honor of Senator John Heinz, The Heinz Cen ter is a nonprofit institution dedicated to improving the scientific and economic foundation for environmental policy through multisectoral collaboration. Focus ing on issues that are likely to confront policymakers within two to five years, the Center creates and fosters collaboration among industry, environmental organiza tions, academia, and government in each of its program areas and projects. -

Salmon, Steelhead, and Trout in California

! "#$%&'(!")**$+*#,(!#',!-.&/)! 0'!1#$02&.'0#! !"#"$%&'(&#)&*+,-.+#"/0&1#$)#& !"#$%&#'"(&))*++*&,$-"./"012*3&#,*1"4#&5'6"7889" PETER B. MOYLE, JOSHUA A. ISRAEL, AND SABRA E. PURDY CENTER FOR WATERSHED SCIENCES, UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, DAVIS DAVIS, CA 95616 -#3$*!&2!1&')*')4! !0:;<=>?@AB?;4C"DDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDD"E" F;4G<@H04F<;"DDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDD"I" :>!B!4J"B<H;4!F;C"KG<LF;0?"=F;4?G"C4??>J?!@""DDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDD"7E" :>!B!4J"B<H;4!F;C"KG<LF;0?"CHBB?G"C4??>J?!@"DDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDD"E7" ;<G4J?G;"0!>FM<G;F!"0<!C4!>"=F;4?G"C4??>J?!@""DDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDD"IE" ;<G4J?G;"0!>FM<G;F!"0<!C4!>"CHBB?G"C4??>J?!@""DDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDD"NO" 0?;4G!>"L!>>?P"C4??>J?!@"DDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDD"OI" 0?;4G!>"0!>FM<G;F!"0<!C4"C4??>J?!@""DDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDD"Q7" C<H4JR0?;4G!>"0!>FM<G;F!"0<!C4"C4??>J?!@""DDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDD"QS" C<H4J?G;"0!>FM<G;F!"0<!C4"C4??>J?!@""DDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDD"9O" G?CF@?;4"0<!C4!>"G!F;T<="4G<H4"DDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDD"SQ" -

Dam Removal Planning in the California Coast Ranges Clare O

The Big Five: Dam Removal Planning in the California Coast Ranges clare O’reilly [email protected] uc Berkeley, mLa-eP, spring 2010 executive summary Dam removal is an increasingly common phenomenon throughout coast the united states, especially in california where reservoirs are ranges rendered obsolete by infilling with sediment from high yield reservoirs catchments. this condition is found in the california coast ranges, with <50% where the mediterranean climate and active faults contribute to remaining capacity reservoir infilling.t his thesis examines five case studies of dams in the california coast ranges, which are being considered for removal because they impound infilled reservoirs and prevent threatened steelhead from accessing potential upstream spawning habitat. the objective is to discern lessons about the dam removal planning process for application to future dam removals. case study analysis focuses on actors involved, the process followed, and an evaluation of risks associated with the proposed removal strategy. a set of recommendations is provided for consideration in development of reservoir sediment modeling results dam removal planning policies. indicating high sedimentation rates in coast ranges. (minear & Kondolf, 2009) Dam Impacts and Reasons for Removal Dams and reservoirs are constructed on rivers to store water for future use, or for hydroelectric power generation (Palmieri et al, 2001). rivers convey water and sediment from surrounding uplands. When a river is impounded by a dam, water flowing from upstream slows down, leading to sediment deposition in a reservoir (morris & Fan, 1998). common engineering practice was to design reservoirs to allow them to fill with sediment slowly, resulting in a finite lifetime for reservoirs and their impounding structures as storage capacity decreased with increasing siltation (Palmieri et al, 2001). -

LA Sustainable Water Project: Los Angeles River Watershed

LA SUSTAINABLE WATER PROJECT: LOS ANGELES RIVER WATERSHED This report is a product of the UCLA Institute of the Environment and Sustainability, UCLA Sus- tainable LA Grand Challenge, and Colorado School of Mines. AUTHORS Katie Mika, Elizabeth Gallo, Laura Read, Ryan September 2017 Edgley, Kim Truong, Terri Hogue, Stephanie Pincetl, Mark Gold ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS UCLA Grand Challenges, Sustainable LA This research was supported by the City of Los 2248 Murphy Hall Angeles Bureau of Sanitation (LASAN). Many Los Angeles, CA 90005-1405 thanks to LASAN for providing ideas and direc- tion, facilitating meetings and data requests, as well as sharing the many previous and current re- UCLA Institute of the Environment and search efforts that provided us with invaluable in- Sustainability formation on which to build. Further, LASAN La Kretz Hall, Suite 300 and LADWP provided data and edits that helped Box 951496 to deepen and improve this report. Any findings, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1496 opinions, or conclusions are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of LASAN. Colorado School of Mines 1500 Illinois Street Golden, CO 80401 We would like to acknowledge the many organiza- tions which facilitated this research through providing data, conversations, reviews, and in- sights into the integrated water management world in the Los Angeles region: LADWP, LAC- DPW, LARWQCB, LACFCD, WRD, WBMWD, MWD, SCCWRP, the Mayor’s Office of Sustaina- bility, and many others. 1 | LA Sustainable Water Project: Los Angeles River Watershed Contents Executive -

Watershed Assets Assessment Report

16. Watershed Assets Assessment Report Jingfen Sheng John P. Wilson Acknowledgements: Financial support for this work was provided by the San Gabriel and Lower Los Angeles Rivers and Mountains Conservancy and the County of Los Angeles, as part of the “Green Visions Plan for 21st Century Southern California” Project. The authors thank Jennifer Wolch for her comments and edits on this report. The authors would also like to thank Frank Simpson for his input on this report. Prepared for: San Gabriel and Lower Los Angeles Rivers and Mountains Conservancy 900 South Fremont Avenue, Alhambra, California 91802-1460 Photography: Cover, left to right: Arroyo Simi within the city of Moorpark (Jaime Sayre/Jingfen Sheng); eastern Calleguas Creek Watershed tributaries, classifi ed by Strahler stream order (Jingfen Sheng); Morris Dam (Jaime Sayre/Jingfen Sheng). All in-text photos are credited to Jaime Sayre/ Jingfen Sheng, with the exceptions of Photo 4.6 (http://www.you-are- here.com/location/la_river.html) and Photo 4.7 (digital-library.csun.edu/ cdm4/browse.php?...). Preferred Citation: Sheng, J. and Wilson, J.P. 2008. The Green Visions Plan for 21st Century Southern California. 16. Watershed Assets Assessment Report. University of Southern California GIS Research Laboratory and Center for Sustainable Cities, Los Angeles, California. This report was printed on recycled paper. The mission of the Green Visions Plan for 21st Century Southern California is to offer a guide to habitat conservation, watershed health and recreational open space for the Los Angeles metropolitan region. The Plan will also provide decision support tools to nurture a living green matrix for southern California.