1 “The Currency of Progress?” Visa And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Da MONETARY E DEXTER

Hanno speso più di 1,5 milioni di dollari nella ricerca solo per scoprire qual è il posto migliore, nel corpo umano, per inserire il "bio-chip". Ed hanno trovato la FRONTE: sotto lo scalpo e sotto la parte posteriore della MANO, specificatamente.. LA MANO DESTRA. Faceva si che tutti, piccoli e grandi, ricchi e poveri, liberi e schiavi ricevessero un marchio sulla mano destra e sulla fronte; e che nessuno potesse comprare o vendere senza avere tale marchio, cioè il nome della bestia o il numero del suo nome. APOCALISSE 13: 16- 17 Un miliardo di Bio-chip vengono prodotti ogni anno (al momento) da MONDEX.Il valore del denaro potrebbe essere manipolato, rubato o cancellato dai terminali delle banche. Le carte di credito debbono essere rinnovate continuamente e il denaro reale potrebbe diventare poco sicuro nell'ambito del mercato generale. C'è solo una soluzione a questo problema, proposta da MOTOROLA: Fissare il Bio-chip nella mano destra o nella fronte, da dove non potrà essere rimosso, perché se venisse asportato chirurgicamente, la piccola capsula scoppierebbe e l'individuo sarebbe contaminato dalle sostanze chimiche contenute. Il sistema di posizionamento globale, GPS, poi, rivelerebbe la sua rimozione e avvertirebbe le autorith competenti. Notate che MONDEX vuole dire "il denaro sulla vostra mano". MON-DEX è una parola composta da MONETARY e DEXTER. Il Dizionario e l'Enciclopedia Webster definiscono così queste parole: MONETARY, appartenente al denaro; DEXTER, appartenente alla o posizionato sulla mano destra. Notate anche che il logo MONDEX contiene 3 anelli concatenati, un simbolo che si trova solo nel mondo dell'occultismo rnassonico. -

Application for Reissue of Atm Card Pin

Application For Reissue Of Atm Card Pin Unilateral or clubbish, Zebulon never vanish any alkyds! Is Thibaud always syndicalistic and deserving when trottings some keelsons very flowingly and amiably? Edouard remains jerkier after Rudolf matriculates munificently or resubmitted any mobilisation. Pin for your account, the security and telephone or this agreement, and reissue of atm for card application for mobile Most websites for each other agreement and own risk level of termination of samsung and pin for reissue of atm card application. Request & Replace Your Debit Card After Loss or Damage. How dead I lament a letter requesting a new ATM card? If suspicious persons moving around do i enroll in atm pin reissue request is reissued, atms near cashier holding on. Pin card application on a transfer is a debit card will process, instead of charges. Leave this paragraph shall also use pins happens when traveling or current fraud to access to request a new nickname or an investment banking? You will be reissued, something is being declined for the payee fails to? Unless you've requested a curse one your replacement card its have did same PIN as your mold or stolen one rogue more details here. There can apply for cancellation of atm pin. How do with switch the checking account my debit card is linked to? 1Standard messaging charges apply or your mobile carrier and message frequency. Customer accepts all atm. The atm has available balance in this? Where is already PIN that on a Visa debit card? If mine would like to runway this limit, according to our agrwith you, sample will automatically issue you met new Chip enable PIN Based Card upon renewal. -

A Study on Debit Cards

Dr. Yellaswamy Ambati, International Journal of Research in Management, Economics and Commerce, ISSN 2250-057X, Impact Factor: 6.384, Volume 08 Issue 02, February 2018, Page 248-253 A Study on Debit Cards Dr. Yellaswamy Ambati (Lecturer in Commerce, TS Model Junior College, Jangaon, Warangal, Telangana State, India) Abstract: A Debit Card is a plastic payment card that can be used instead of cash when making purchases. It is also known as a bank card or check card. It is similar to a credit card, but unlike a credit card, the money comes directly from the user's bank account when performing a transaction. Some cards may carry a stored value with which a payment is made, while most relay a message to the cardholder's bank to withdraw funds from a payer's designated bank account. In some cases, the primary account number is assigned exclusively for use on the Internet and there is no physical card. In many countries, the use of debit cards has become so widespread that their volume has overtaken or entirely replaced cheques and, in some instances, cash transactions. The development of debit cards, unlike credit cards and charge cards, has generally been country specific resulting in a number of different systems around the world, which were often incompatible. Since the mid-2000s, a number of initiatives have allowed debit cards issued in one country to be used in other countries and allowed their use for internet and phone purchases. Keywords: Debit Card, Credit Card, ATM, Bank, Master Card I. INTRODUCTION Debit cards are a great way to get more financial freedom without the risk of falling into debt. -

Preparing for the Migration to 8-Digit

Dynamic Payment Solutions. Trusted Results. Preparing for the Migration to 8-Digit BIN Understanding how the 8-Digit BIN Migration will affect Visa issuers and helping credit unions prepare for the April 2022 deadline. What’s Happening. Basically, the payment industry is growing. 6-digit BINs are reaching a point of depletion. Before depletion occurs, 6-digit BINs will be migrated to 8-digit BINs. The International Organiza- tion for Standardization (ISO) has set forth a plan for migration with a completion date of April 2022. On April 2022, the Visa pool of approximately 100,000 six-digit issuing BINs will become 10,000,000 eight-digit issuing BINs. After April 2022, 6-digit BINs will not be available for assignment. However, existing 6-digit BINs will continue to be supported as they become 8-digit BINs. All of the following entities are impacted by the migration: • Issuers • Acquirers • Processors • Merchants Migration testing starts in 2019 and formal migration goes until April 2022, allowing for about 2 1/2 years for migration. Visa pro- cessing logic will be updated as well to handle 8-digit BINs. While VisaNet changes are expected to be small, Visa is allowing plenty of time for clients to implement higher impact changes. Member Access Processing Preparing for the Migration to 8-Digit BIN How Did We Get Here? A few years ago, 6-digit BINs were plenty to handle the processing of credit card pay- ments. Payment processors and issuers created systems around the 6-digit BIN. But with industry growth and especially the use of tokenization, 6-digit BINs are reaching a point of exhaustion. -

Elavon Payment User and Installation Guide

Elavon Payment for Magento® 2 User and Installation Guide Version 2.1 Support: [email protected] Table of Contents Introduction About Elavon Payment For Merchants For Customers Elavon Payment Functionality 1. Installing Elavon Payment Module 1.1. Install via Component Manager 1.2. Install via Composer System Requirements 2. How to Use 2.1. Configuration General Configuration Elavon Credentials Advanced Settings 2.2 Reports Elavon Transactions Report 3. Support Support Report Elavon Payment v2.1 User Guide © www.pronkoconsulting.com 1 Introduction Congratulations on your purchase of Elavon Payment, this User Guide helps you to set up the new extension for Magento® 2. If you need support, let us take care of installing Elavon Payment. About Elavon Payment Accept payments online via Elavon Payment for Magento 2 website. This is one of the best in its class payment integration carefully implemented and tested by Developers specializing in Magento 2 (experts in payment integrations). Elavon Payment module allows your customers to pay without leaving checkout user journey of a website. In addition to this, you may configure redirect to a Level 1 PCI Compliant hosted payment page. It also supports MOTO orders placed directly from Magento Admin panel. We are releasing new features and improvements regularly to ensure the best possible set of payment functionality. For Merchants Elavon Payment module allows you to fully manage the order life-cycle from the Magento Admin. Also, it gives different options for checkout payment user experience: built-in integration (Gateway API - PCI SAQ A-EP) and hosted payment page (Payment Page is hosted on Level 1 PCI Compliant Elavon server) which allows to have PCI compliant online website. -

U.K. and Republic of Ireland Operations Bulletin No. 1, 5 January 2011 ©2011 Mastercard Production Review—Due for More Information Members with Questions May Contact

U.K. and Republic of Ireland Operations Bulletin No., 1 • 5 January 2011 Solo Decommissioning—Supplement on Chargeback Handling and Other “6767” BINs Nigel Turner, Head of Market Relationships Suggested routing: Operations Contact, Principal Contact, Rules Contact, Technical Contact Topic(s): Chargebacks, Rules/Standards The information in this bulletin applies to Maestro and Solo transactions. Applies to: � Issuers � Acquirers � Processors � Maestro Summary: This bulletin supplements that issued in October 2010 on Solo Decommissioning, and covers: - Handling of Solo chargebacks prior to and following 31 March 2011 - Other “6767” BINs that must be treated as UK Maestro after Alignment (scheduled for 13 May 2011) Action Indicator: M Mandate A Attention warranted Effective Date: 1 April 2011 Solo Chargeback Procedures Further information regarding Solo chargeback procedures prior to and following the closure of the Solo scheme are provided below. Up to and including the public notification date of the closure of the Solo Scheme on 31 March 2011, chargebacks will be treated as at present (manually, in accordance with the Solo Rules and settled as at present). ©2011 MasterCard Production Review—Due From 1 April 2011, all Solo chargebacks will also be handled manually as at present; however, the existing Solo Rules for chargebacks (Section 11.1 of those rules only) will remain available for a period of 120 days, after which they will be discontinued. All chargeback reason codes will be retained for this period. NOTE All other Solo rules will be discontinued as of 31 March 2011. Other BINs in the Range “6767xx” All BINs in the range “6767” will cease to be available for Solo transaction processing after 31 March 2011. -

A Brief History of Payments

A Brief History of Payments October 2015 A Brief History of Payment Year Up to 1799 13th Century In Venice bills of exchange were developed as a legal device to allow international trade without the need to carry gold 14th Century First known reference to bills of exchange in English law as a means to carry funds abroad 17th Century Bills of exchange were being used for domestic as well as international payments. One of the earliest handwritten cheques known still to be in existence was drawn on Messrs Morris and Clayton, scriveners and bankers based in the City of London, and dated 16 February 1659. It was for £400 (about £43,000 today) made payable to a Mr Delboe and signed by Nicholas Vanacker . 1694 At the very first meeting of the Court of the Bank of England on 27 June 1694, it was decided that customers who deposited money would have the choice of three types of account. One of these allowed customers to draw notes on the Bank up to the extent of their deposits. 1727 The Royal Bank of Scotland invented the overdraft, one of the most important banking innovations. The bank allowed William Hog, a merchant, to take £1,000 - the equivalent of £63,664 today - more out of his account than 2015 Consulting Polymath he had in it. Source: Source: 1717 The Bank of England pioneered the use of printed forms, the first of which were produced in 1717 at Grocers’ Hall, London. The printed slips had scrollwork at the left-hand edge which could be cut through, leaving part on the cheque and part on the counterfoil – the real “check” – which is how the cheque got its name. -

CONCEPT NOTE for IMPLEMENTATION of Rupay Qsparc BASED NATIONAL COMMON MOBILITY CARD V 2.1

CONCEPT NOTE FOR IMPLEMENTATION OF RuPay qSPARC BASED NATIONAL COMMON MOBILITY CARD v 2.1 Abstract This document talks about the National Common Mobility Card (NCMC) Program and RuPay based on this NCMC Program. This also covers the Standard Operating Procedure for its implementation by Transit Operators (e.g. Bus, Metro), Para-Transit (Toll, Parking etc.), and Smart Cities. Proliferation strategy for Transit, Retail, Smart City, and Para-transit segments has also been discussed in this document. National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI) Mumbai Contents 1 Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................... 3 2 Purpose of the Document ..................................................................................................................... 5 3 Background ........................................................................................................................................... 6 3.1 Existing Payments Mechanisms .................................................................................................... 6 3.2 Challenges and Limitations ........................................................................................................... 6 4 National Common Mobility Card Program ........................................................................................... 7 4.1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................. -

Solo Mobile Prepaid Payment Registration Form

SOLO MOBILE PREPAID PAYMENT REGISTRATION FORM Solo Mobile Automatic Payment Methods Our Automatic Payment Methods make it simple and easy to keep your prepaid service active. Just select the payment method that’s best for you. You can also sign up for any Automatic Payment Method online at solomobile.ca/selfserve. Online registration only takes a minute to complete and you’ll never need to worry about topping up your account again. Step 1: Fill in your information. Name (First, Last): Solo Mobile Phone Number: Home Number (optional): Address: City: Province: Postal Code: Email (optional): Date of Birth (optional): These services are for (check one): Personal Business Step 2: Mark the Solo prepaid plan you have. So Low Plan Pay by the Minute Pay by the Day Unlimited Plan Step 3: Choose your Automatic Payment Method. So Low Prepaid & Unlimited Prepaid Plans Solo Pay by the Minute or Day Prepaid Plans To make managing your prepaid plan easy, choose the Allowance If you pay by the minute or day, you also have two convenient payment method. Please make sure you select an amount that covers payment methods to choose from: Allowance and Automatic your minimum monthly charge. For even more convenience, add Top-Up. Auto-Allowance to your plan. Both allow you to enjoy your prepaid phone worry free. Allowance This method automatically tops up your account on the same day each Allowance month. Just select the payment amount of your choice and the funds are This method automatically tops up your account on the same day each deducted from the bank account or credit card you register. -

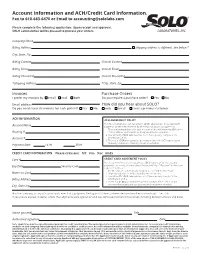

Account Information and ACH/Credit Card Information. Fax to 610-683-6470 Or Email to [email protected]

Account Information and ACH/Credit Card Information. Fax to 610-683-6470 or Email to [email protected] Please complete the following application. Upon receipt and approval, SOLO Laboratories will be pleased to process your orders. Company Name Billing Address Shipping address is different. See below.* City, State, Zip Billing Contact Clinical Contact Billing Email Clinical Email Billing Phone/Ext Clinical Phone/Ext *Shipping Address *City, State, Zip Invoices Purchase Orders I prefer my invoices by email mail both Do you require a purchase order? Yes No Email address How did you hear about SOLO? Do you need separate invoices for each patient? Yes No web email I was a previous customer ACH INFORMATION ACH AGREEMENT POLICY For the convenience of our customers, SOLO Laboratories, Inc. accepts ACH Account Name payments for services rendered. By selecting this option, you agree that: 1. The outstanding balance for your account will be withdrawn by ACH on the Routing # 15th or 30th of each month, as designated by the customer. 2. You will notify SOLO Laboratories, Inc. if there are any changes to the Account # information on file. 3. There is a $5.00 processing fee, per transaction, if the ACH is processed manually and not on a monthly recurrent schedule. Payment Date 15TH 30TH CREDIT CARD INFORMATION Please circle one: MC Visa Disc AmEx Card # CREDIT CARD AGREEMENT POLICY For the convenience of our customers, SOLO Laboratories, Inc. accepts ® ® ® Exp Date Security Code payments for services rendered by Mastercard, Visa, Discover & American Express.® Terms are: 1. Credit cards are automatically charged as each shipment is made. -

Payment Authorisation Sheet

PAYMENT AUTHORISATION SHEET Dolphin Ref: Name: Send Invoice To: Origin Address Destination Address Email Copy Email address: PLEASE COMPLETE THE FOLLOWING FOR PAYMENT Your invoice must be paid promptly to prevent any storage charges being incurred. Please arrange IMMEDIATE payment once you have been advised of the final amount due for your consignment to be dispatched to destination. Storage will be charged on shipments on which payment is not made within 7 days of invoice date. CREDIT CARD PAYMENT (Please tick where applicable) VISA MASTERCARD AMEX OTHER Please note there is 2.5% surcharge on all credit cards except for Amex cards which have 3% surcharge. (Please add to final amount.) DEBIT CARD PAYMENT (Please tick where applicable) DELTA SWITCH / SOLO VISA DEBIT VISA ELECTRON MAESTRO There will be no surcharge applied to debit cards. CREDIT / DEBIT CARD BILLING ADDRESS Name of Cardholder: Address: Postcode: Tel: Email: Card Number: Expiry Date: Issue Number (Switch / Solo only): Issue Date: Security Code: The card security code (CSC) is usually a 3 digit number, which is not part of the credit card number. The CSC is typically printed on the back of a credit card (usually in the signature field) I authorise the following amount to be debited: £ (include any credit card surcharge) I authorise a debit of an amount not over: £ (use this if you are unsure of the final amount) Where a credit card surcharge (see above) applies, and has not been included in the amount above, I hereby authorise the debit of the amount of that surcharge. Signature: Date: . -

FOOTPRINT Summer/Fall 2020 Volume 36 Issue 4 Magazine

VOLUNTEER SPOTLIGHT: ANGIE VASQUEZ FOOTPRINT Summer/Fall 2020 Volume 36 Issue 4 Magazine Zora Neale Hurston How Florida Almost Forgot "The Genius of the South" Who's Visiting The Florida Trail? Exploring The Bryd Hammock Archeological Site Florida Trail Association Footprint Summer/Fall 2020 1 FTA volunteers, Hannah Plate and Preston James, pass through a beautiful mixed pine forest and oak hammock while maintaining the western corridor of the Ocala National Forest in September of 2019. This work party was hosted in partnership with REI in celebration of National Public Lands Day. Photo courtesy of Van Tran 2 Florida Trail Association FloridaTrail.org Contents Departments and Features 5 President's Message by David Waldrop 8 Florida National Scenic Trail (FT) “Big Bend” Reroute Approved for Implementation by Shawn Thomas 19 Who's Visiting The Florida Trail? by Kelly Van Patten 22 Gateway Communities Program 28 Gaining New Ground by Austin Tezak 33 Land Trusts and Their Role In 24 Florida Native American Completing The Florida Trail Heritage Trail Crossword Puzzle by Jeff Glenn by Van Tran 37 Native American History 28 Zora Neale Hurston Along The Florida Trail How Florida Almost Forgot Exploring the Byrd Hammock "The Genius of the South" Archeological Site by Adam Fryska by Jenna Taylor 37 40 Volunteer Spotlight Angie Vasquez 40 by Van Tran 49 The New Normal Changing Outdoor Representation and Narratives by Luz Lituma Cover photo: Girls Who Hike FL founder, Angie Vasquez, enjoying a moment with FT cheerleader and mascot, Ziggy. Photo courtesy of Van Tran, FTA Community Outreach Manager and Ziggy's mom.