Do Employers Value Return Migrants? an Experiment on the Returns to Foreign Work Experience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Participating Universities of the HUMAP

List of Participating Universities of the HUMAP (As of April, 2015) Japan Ashiya University (Taiwan) Kai Nan University (Hyogo) Himeji Dokkyo University National Kaohsiung First University of Science and Technology (25) Hyogo University National Taichung University Hyogo University of Teacher Education National Taipei University Kansai University of International Studies National Taiwan University of Arts Kobe City College of Nursing National Taiwan Ocean University Kobe City University of Foreign Studies National Yunlin University of Science and Technology Kobe College Providence University Kobe Design University Shu-Te University Kobe Gakuin University Southern Taiwan University of Technology Kobe International University Tunghai University Kobe Pharmaceutical University Indonesia Airlangga Univeresity Kobe Shinwa Women's University (11) Bung Hatta University Kobe Shoin Women's University Darma Persada University Kobe University Gadjah Mada University Kobe Women's University Hasanuddin University Konan University Institut Teknologi Bandung Konan Women's University Institut Teknologi Sepuluh Nopember Koshien University Satya Wacana Christian University Kwansei Gakuin University Syiah Kuala University Mukogawa Women's University Udayana University Otemae University University of Indonesia Sonoda Women's University Korea Ajou University University of Hyogo* (29) Cheju National University University of Marketing and Distribution Sciences Chosun University Dong-A University Australia Australian Maritime College Dong Seo University (11) Curtin -

Ang Higante Sa Gubat

Isabela School of Arts and Trades, Ilagan Quirino Isabela College of Arts and Technology, Cauayan Cagayan Valley College of Quirino, Cabarroguis ISABELA COLLEGES, ▼ Cauayan Maddela Institute of Technology, Maddela ISABELA STATE UNIVERSITY, ▼ Angadanan Quirino Polytechnic College, Diffun ISABELA STATE UNIVERSITY, ▼Cabagan QUIRINO STATE COLLEGE ▼ Diffun, Quirino ISABELA STATE UNIVERSITY, Cauayan Polytechnic College, ▼Cauayan ISABELA STATE UNIVERSITY, ▼Echague Region III (Central Luzon ) ISABELA STATE UNIVERSITY, ▼Ilagan ISABELA STATE UNIVERSITY, ▼Jones ISABELA STATE UNIVERSITY, ▼Roxas Aurora ISABELA STATE UNIVERSITY, ▼San Mariano AURORA STATE COLLEGE OF TECHNOLOGY, ▼ Baler ISABELA STATE UNIVERSITY, ▼San Mateo Mount Carmel College, Baler Mallig Plains College, Mallig Mount Carmel College of Casiguran, Casiguran Metropolitan College of Science and Technology, Santiago Wesleyan University Philippines – Aurora Northeast Luzon Adventist School of Technology, Alicia Northeastern College, Santiago City Our Lady of the Pillar College of Cauayan, Inc., Cauayan Bataan Patria Sable Corpus College, Santiago City AMA Computer Learning Center, Balanga Philippine Normal University, Alicia Asian Pacific College of Advanced Studies, Inc., Balanga Southern Isabela College of Arts and Trade, Santiago City Bataan (Community) College, Bataan Central Colleges, Orani S ISABELA STATE UNIVERSITY ▼ Echague, Isabela Bataan Heroes Memorial College, Balanga City Saint Ferdinand College-Cabagan, Cabagan BATAAN POLYTECHNIC STATE COLLEGE, ▼Balanga City Saint Ferdinand -

Repeaters First Timers School Performance Of

The performance of schools in the September 2018 Registered Electrical Engineer Licensure Examination in alphabetical order as per R.A. 8981 otherwise known as PRC Modernization Act of 2000 Section 7(m) "To monitor the performance of schools in licensure examinations and publish the results thereof in a newspaper of national circulation" is as follows: SEPTEMBER 2018 R. E. E. LICENSURE EXAMINATION PERFORMANCE OF SCHOOLS IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER SEQ. FIRST TIMERS REPEATERS OVERALL PERFORMANCE NO. SCHOOL PASSED FAILED COND TOTAL % PASSED PASSED FAILED COND TOTAL % PASSED PASSED FAILED COND TOTAL % PASSED ABE INTERNATIONAL COLLEGE 1 OF BUSINESS & ECONOMICS- 1 0 0 1 100.00% 0 0 0 0 0.00% 1 0 0 1 100.00% BACOLOD ABRA STATE INST. OF SCIENCE & 2 TECH.(ABRA IST)-BANGUED 3 7 0 10 30.00% 1 2 0 3 33.33% 4 9 0 13 30.77% ADAMSON UNIVERSITY 3 29 7 0 36 80.56% 2 8 0 10 20.00% 31 15 0 46 67.39% ADVENTIST INTERNATIONAL 4 INSTITUTE OF ADVANCED 0 0 0 0 0.00% 0 1 0 1 0.00% 0 1 0 1 0.00% STUDIES AGUSAN BUSINESS & ART 5 FOUNDATION, INC. 0 0 0 0 0.00% 1 0 0 1 100.00% 1 0 0 1 100.00% ALDERSGATE COLLEGE 6 1 1 0 2 50.00% 0 1 0 1 0.00% 1 2 0 3 33.33% ALEJANDRO COLLEGE 7 0 0 0 0 0.00% 0 1 0 1 0.00% 0 1 0 1 0.00% AMA COMPUTER COLLEGE- 8 ZAMBOANGA CITY 0 1 0 1 0.00% 0 0 0 0 0.00% 0 1 0 1 0.00% ANDRES BONIFACIO COLLEGE 9 6 3 0 9 66.67% 0 3 0 3 0.00% 6 6 0 12 50.00% ANTIPOLO SCHOOL OF NURSING 10 & MIDWIFERY 1 0 0 1 100.00% 0 0 0 0 0.00% 1 0 0 1 100.00% ATENEO DE DAVAO UNIVERSITY 11 3 0 0 3 100.00% 0 0 0 0 0.00% 3 0 0 3 100.00% AURORA STATE COLLEGE OF 12 TECHNOLOGY 12 2 -

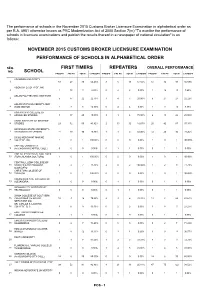

Performance of Schools in the November 2015 Customs Broker Licensure Examination in Alphabetical Order As Per R.A

The performance of schools in the November 2015 Customs Broker Licensure Examination in alphabetical order as per R.A. 8981 otherwise known as PRC Modernization Act of 2000 Section 7(m) "To monitor the performance of schools in licensure examinations and publish the results thereof in a newspaper of national circulation" is as follows: NOVEMBER 2015 CUSTOMS BROKER LICENSURE EXAMINATION PERFORMANCE OF SCHOOLS IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER SEQ. FIRST TIMERS REPEATERS OVERALL PERFORMANCE NO. SCHOOL PASSED FAILED TOTAL % PASSED PASSED FAILED TOTAL % PASSED PASSED FAILED TOTAL % PASSED ADAMSON UNIVERSITY 1 53 27 80 66.25% 8 5 13 61.54% 61 32 93 65.59% AGONCILLO COLLEGE, INC 2 1 10 11 9.09% 0 2 2 0.00% 1 12 13 7.69% AKLAN POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE 3 5 17 22 22.73% 1 4 5 20.00% 6 21 27 22.22% AKLAN STATE UNIVERSITY-NEW 4 WASHINGTON 1 7 8 12.50% 0 4 4 0.00% 1 11 12 8.33% ASIA PACIFIC COLLEGE OF 5 ADVANCED STUDIES 3 17 20 15.00% 3 1 4 75.00% 6 18 24 25.00% ASIAN INSTITUTE OF MARITIME 6 STUDIES 23 32 55 41.82% 2 10 12 16.67% 25 42 67 37.31% BATANGAS STATE UNIVERSITY- 7 BATANGAS CITY (PBMIT) 71 19 90 78.89% 1 1 2 50.00% 72 20 92 78.26% BICOL MERCHANT MARINE 8 COLLEGE, INC. 1 0 1 100.00% 0 0 0 0.00% 1 0 1 100.00% CAPITOL UNIVERSITY 9 (for.CAGAYAN CAPITOL COLL.) 0 0 0 0.00% 0 1 1 0.00% 0 1 1 0.00% CDH ALLIED MEDICAL COLLEGES 10 (FOR.CALAMBA DOCTORS) 1 0 1 100.00% 0 0 0 0.00% 1 0 1 100.00% CENTRAL LUZON COLLEGE OF 11 SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY- 5 2 7 71.43% 2 0 2 100.00% 7 2 9 77.78% OLONGAPO CHRISTIAN COLLEGE OF 12 TANAUAN 1 0 1 100.00% 0 0 0 0.00% 1 0 1 100.00% COLEGIO DE STA. -

Table 9. Private Higher Education Institutions Faculty-Student Ratio: AY 2016-17

Table 9. Private Higher Education Institutions Faculty-Student Ratio: AY 2016-17 Number of Number of Faculty/ Region Name of Private Higher Education Institution Students Faculty Student Ratio 01 - Ilocos Region The Adelphi College 554 25 1:22 Malasiqui Agno Valley College 737 32 1:23 Asbury College 541 17 1:32 Asiacareer College Foundation 144 15 1:10 Baccarra Medical Center School of Midwifery 24 10 1:2 CICOSAT Colleges 825 42 1:20 Colegio de Dagupan 3,567 82 1:44 Dagupan Colleges Foundation 110 20 1:6 Data Center College of the Philippines of Laoag City 1,602 58 1:28 Divine Word College of Laoag 1,567 90 1:17 Divine Word College of Urdaneta 63 17 1:4 Divine Word College of Vigan 735 50 1:15 The Great Plebeian College 514 46 1:11 Lorma Colleges 2,816 136 1:21 Luna Colleges 1,794 20 1:90 University of Luzon 6,149 188 1:33 Lyceum Northern Luzon 1,636 62 1:26 Mary Help of Christians College Seminary 58 18 1:3 Northern Christian College 617 57 1:11 Northern Luzon Adventist College 513 49 1:10 Northern Philippines College for Maritime, Science and Technology 2,524 76 1:33 Northwestern University 4,129 169 1:24 Osias Educational Foundation 383 14 1:27 Palaris College 377 28 1:13 Page 1 of 65 Number of Number of Faculty/ Region Name of Private Higher Education Institution Students Faculty Student Ratio Panpacific University North Philippines-Urdaneta City 2,824 62 1:46 Pangasinan Merchant Marine Academy 3,458 27 1:128 Perpetual Help College of Pangasinan 1,031 44 1:23 Polytechnic College of La union 1,597 41 1:39 Philippine College of Science and Technology 2,429 104 1:23 PIMSAT Colleges-Dagupan 1,653 40 1:41 Saint Columban's College 135 11 1:12 Saint Louis College-City of San Fernando 4,761 158 1:30 Saint Mary's College Sta. -

Strategic Learning Methodologies and Collaborations in Modular Distance Learning

International Journal of Management Studies and Social Science Research STRATEGIC LEARNING METHODOLOGIES AND COLLABORATIONS IN MODULAR DISTANCE LEARNING Archielyn A. Semanero, Ma.Ed, LPT, Ph.D (cand.) Cornelia M. de Jesus Memorial School and Sir Dr. Benedict DC. David, KCR, Ph.D, DHC, CA Adamson University Universidad de Manila University of Santo Tomas IJMSSSR 2021 VOLUME 3 ISSUE 2 MARCH – APRIL ISSN: 2582 - 0265 Abstract: It is clearly visible that the present COVID-19 pandemic has brought extraordinary challenges and has affected the educational sectors. The Department of Education being the pillars of literacy or Filipino children does the necessary innovations and interventions to continue the learning despite pandemic. The department is indeed eager to address the challenges in the basic education for the school year 2020-2021 through its Basic Education Learning Continuity Plan (BE-LCP) under DepEd Order No. 012, s. 2020. This is also the grass root of the rise of different teaching modality in the absence of face to face. Modular distance learning is one of the most widely used teaching modality in the country. This type of teaching modality features individualized instruction that allows learners to use printed self-learning modules (SLMs) which are made aligned to Most Essential Learning Competencies that are applicable to the learners. Keywords: Learning, Asynchronous Learning, Collaborations, Strategic Learning RESEARCH RATIONALE The Corona virus Disease of 2019 (COVID-19) is a highly fatal and fast spreading infectious disease caused by Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The case of this disease was identified in December 2019 in Wuhan, the capital of China's Hubei province, and has since spread globally, resulting in the ongoing 2019–20 coronavirus pandemic. -

Development of an Electronic Nose for Smell Categorization Using Artificial Neural Network

Journal of Advances in Information Technology Vol. 12, No. 1, February 2021 Development of an Electronic Nose for Smell Categorization Using Artificial Neural Network Dailyne Macasaet, Argel Bandala, Ana Antoniette Illahi, Elmer Dadios, Sandy Lauguico, and Jonnel Alejandrino De La Salle University-Manila, Philippines Email: {dailyne_macasaet, argel.bandala, ana.illahi, elmer.dadios, sandy_lauguico, jonnel_alejandrino}@dlsu.edu.ph Abstract—Electronic Nose employs an array of gas sensors recognition algorithm and integrating multi-sensor array and has been widely used in many specific applications for therefore creating an artificial olfactory system which we the analysis of gas composition. In this study, electronic technically refer to as electronic nose [3]. nose, integrating ten MQ gas sensors, is intended to model Artificial olfaction had its beginnings with the olfactory system which generally classifies smells based on invention of the first gas multi-sensor array in 1982 [4]. ten basic categories namely: fragrant, sweet, woody/resinous, pungent, peppermint, decaying, chemical, From this, several works have been done in the past citrus, fruity, and popcorn using artificial neural network as attempting to mimic the mammalian olfactory system its pattern recognition algorithm. Initial results suggest that employing different methods. J. White et al. (1998) used four (Pungent, Chemical, Peppermint, and Decaying) an array of fiber-optic chemosensors and sent the outputs among the ten classifications are detectable by the sensors of the sensors to an olfactory bulb [5]. They then used a commercially available today while technology for delay line neural network to perform recognition. In the classifying the remaining six is still under development. year 2000, a study conducted by S Schiffman et al. -

The Successful Examinees Who Garnered the Ten (10) Highest Places in the November 2014 Nurse Licensure Examination Are the Following

The successful examinees who garnered the ten (10) highest places in the November 2014 Nurse Licensure Examination are the following: RANK NAME SCHOOL RATING (%) PAMANTASAN NG LUNGSOD NG 1 ELIJAH CATACUTAN LEGASPI 86.80 MAYNILA WESLEYAN UNIVERSITY- 2 GEASTYNE LAUREN GALANG NOLIDO 86.60 PHILIPPINES-CABANATUAN CITY ST. SCHOLASTICA'S COLLEGE- JANELLE JOY FERNANDEZ PONFERRADA 86.60 TACLOBAN MARIANO MARCOS STATE RALF JAY VILLANUEVA RETOTAL 86.60 UNIVERSITY-BATAC 3 JOBELLE KASPER BATANGAN AGMATA NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY 86.20 ELLAINE MARIE TIBURCIO LAURETA SAINT MARY'S UNIVERSITY 86.20 SAN LORENZO RUIZ COLLEGE OF CHERYL CUBI YMAS 86.20 ORMOC 4 NORHANA ABDULKARIM ALI ARELLANO UNIVERSITY-MANILA 86.00 JOSE RIZAL MEMORIAL STATE RONNIE VINCENT BOLASCO ANTIVO 86.00 UNIVERSITY-DAPITAN COLEGIO SAN AGUSTIN-BACOLOD CORLENE JOIE LINAUGO CORTEZ 86.00 CITY MICHELLE LAUREN NEPOMUCENO XAVIER UNIVERSITY 86.00 ESTRELLA UNIVERSITY OF EASTERN KELVIN KENN BRILLANTE MAGDARAOG 86.00 PHILIPPINES-CATARMAN UNIVERSITY OF THE PHILIPPINES- ANATOLE GAIL PARIAN VALLEJOS 86.00 MANILA 5 ROGER JOHN NECESITO ASTROLABIO SAN PEDRO COLLEGE-DAVAO CITY 85.80 ILIGAN MEDICAL CENTER COLLEGE, IVAN GARDE REDUBLADO 85.80 INC. UNIVERSIDAD DE MANILA (CITY JOSHUA CALEB SANCHEZ UGTO 85.80 COLL. OF MANILA) 6 JEWELL MARI ELAINE ADVINCULA DAVID ARELLANO UNIVERSITY-MANILA 85.60 MARY DOMINICA RAYMUNDO FUENTES SAINT JUDE COLLEGE-MANILA 85.60 JG MARIE PLANA NAVIGAR CENTRAL PHILIPPINE UNIVERSITY 85.60 ARGIE HUERVAS SILUBRICO SAINT PAUL UNIVERSITY-ILOILO 85.60 EMMANUEL LAMIS ZALDIVIA RIVERSIDE COLLEGE -

Far Eastern University, Incorporated FEU

CR03138-2017 SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION SEC FORM ACGR ANNUAL CORPORATE GOVERNANCE REPORT 1. Report is Filed for the Year May 8, 2017 2. Exact Name of Registrant as Specified in its Charter FAR EASTERN UNIVERSITY, INC. 3. Address of principal office Nicanor Reyes Street, Sampaloc, Manila Postal Code 1015 4.SEC Identification Number PW538 5. Industry Classification Code(SEC Use Only) 6. BIR Tax Identification No. 000-225-442 7. Issuer's telephone number, including area code (632) 735-8686 8. Former name or former address, if changed from the last report - The Exchange does not warrant and holds no responsibility for the veracity of the facts and representations contained in all corporate disclosures, including financial reports. All data contained herein are prepared and submitted by the disclosing party to the Exchange, and are disseminated solely for purposes of information. Any questions on the data contained herein should be addressed directly to the Corporate Information Officer of the disclosing party. Far Eastern University, Incorporated FEU PSE Disclosure Form ACGR-1 - Annual Corporate Governance Report Reference: Revised Code of Corporate Governance of the Securities and Exchange Commission Description of the Disclosure Attached is the 2016 Annual Corporate Governance Report (ACGR) of Far Eastern University, Inc., in compliance with SEC Memorandum Circular No. 20, Series of 2016. Filed on behalf by: Name Santiago Jr. Garcia Designation Corporate Secretary/Compliance Officer SUMMARY OF ACGR UPDATES FOR 2016 A. BOARD MATTERS Board Of Directors - Composition of the Board, p. 5 - Summary of the Corporate Governance Policy that the BOD has adopted, p. 5-6 - Directorship in Other Companies, p. -

Microsoft Schools

Microsoft Schools Region Country State Company APAC Vietnam THCS THẠCH XÁ APAC Korea GoYang Global High School APAC Indonesia SMPN 12 Yogyakarta APAC Indonesia Sekolah Pelita Harapan Intertiol APAC Bangladesh Bangladesh St. Joseph School APAC Malaysia SMK. LAJAU APAC Bangladesh Dhaka National Anti-Bullying Network APAC Bangladesh Basail government primary school APAC Bangladesh Mogaltula High School APAC Nepal Bagmati BernHardt MTI School APAC Bangladesh Bangladesh Letu mondol high school APAC Bangladesh Dhaka Residential Model College APAC Thailand Sarakhampittayakhom School English Program APAC Bangladesh N/A Gabtali Govt. Girls' High School, Bogra APAC Philippines Compostela Valley Atty. Orlando S. Rimando National High School APAC Bangladesh MOHONPUR GOVT COLLEGE, MOHONPUR, RAJSHAHI APAC Indonesia SMAN 4 Muaro Jambi APAC Indonesia MA NURUL UMMAH LAMBELU APAC Bangladesh Uttar Kulaura High School APAC Malaysia Melaka SMK Ade Putra APAC Indonesia Jawa Barat Sukabumi Study Center APAC Indonesia Sekolah Insan Cendekia Madani APAC Malaysia SEKOLAH KEBANGSAAN TAMAN BUKIT INDAH APAC Bangladesh Lakhaidanga Secondary School APAC Philippines RIZAL STI Education Services Group, Inc. APAC Korea Gyeonggi-do Gwacheon High School APAC Philippines Asia Pacific College APAC Philippines Rizal Institute of Computer Studies APAC Philippines N/A Washington International School APAC Philippines La Consolacion University Philippines APAC Korea 포항제철지곡초등학교 APAC Thailand uthaiwitthayakhom school APAC Philippines Philippines Isabel National Comprehensive School APAC Philippines Metro Manila Pugad Lawin High School APAC Sri Lanka Western Province Wise International School - Sri Lanka APAC Bangladesh Faridpur Govt. Girls' High School, Faridpur 7800 APAC New Zealand N/A Cornerstone Christian School Microsoft Schools APAC Philippines St. Mary's College, Quezon City APAC Indonesia N/A SMA N 1 Blora APAC Vietnam Vinschool Thành phố Hồ Chí APAC Vietnam Minh THCS - THPT HOA SEN APAC Korea . -

Participating HUMAP Universities

Participating HUMAP Universities Area the name of the university Area the name of the university Universities Japan Ashiya University (Taipei China) KaiNan University National Kaohsiung First University of in Hyogo (26) Himeji Dokkyo University Science and Technology (26) Hyogo University NationalTaichung University of Education Hyogo University of Teacher Education National Taipei University Kansai University of International Studies National Taiwan University of Arts Kobe City College of Nursing National Taiwan Ocean University National Yunlin University of Science Kobe City University of Foreign Studies and Technology Kobe College National United University Kobe Design University Providence University Kobe Gakuin University Shu Te University Southern Taiwan University of Science Kobe International University and Technology Kobe Pharmaceutical University Tunghai University Kobe Shinwa Women's University National Central University Kobe Shoin Women's University Indonesia Airlangga Univeresity Kobe University (11) Bung Hatta University Kobe Women's University Darma Persada University Konan University Gadjah Mada University Konan Women's University Hasanuddin University Koshien University Institut Teknologi Bandung Kwansei Gakuin University Institut Teknologi Sepuluh Nopember Mukogawa Women's University Satya Wacana Christian University Otemae University Syiah Kuala University Sonoda Women's University Udayana University University of Hyogo University of Indonesia University of Marketing and Distribution Sciences Korea Ajou University -

Private Higher Education Institutions Faculty-Student Ratio: AY 2017-18

Table 11. Private Higher Education Institutions Faculty-Student Ratio: AY 2017-18 Number of Number of Faculty/ Region Name of Private Higher Education Institution Students Faculty Student Ratio 01 - Ilocos Region The Adelphi College 434 27 1:16 Malasiqui Agno Valley College 565 29 1:19 Asbury College 401 21 1:19 Asiacareer College Foundation 116 16 1:7 Bacarra Medical Center School of Midwifery 24 10 1:2 CICOSAT Colleges 657 41 1:16 Colegio de Dagupan 4,037 72 1:56 Dagupan Colleges Foundation 72 20 1:4 Data Center College of the Philippines of Laoag City 1,280 47 1:27 Divine Word College of Laoag 1,567 91 1:17 Divine Word College of Urdaneta 40 11 1:4 Divine Word College of Vigan 415 49 1:8 The Great Plebeian College 450 42 1:11 Lorma Colleges 2,337 125 1:19 Luna Colleges 1,755 21 1:84 University of Luzon 4,938 180 1:27 Lyceum Northern Luzon 1,271 52 1:24 Mary Help of Christians College Seminary 45 18 1:3 Northern Christian College 541 59 1:9 Northern Luzon Adventist College 480 49 1:10 Northern Philippines College for Maritime, Science and Technology 1,610 47 1:34 Northwestern University 3,332 152 1:22 Osias Educational Foundation 383 15 1:26 Palaris College 271 27 1:10 Page 1 of 65 Number of Number of Faculty/ Region Name of Private Higher Education Institution Students Faculty Student Ratio Panpacific University North Philippines-Urdaneta City 1,842 56 1:33 Pangasinan Merchant Marine Academy 2,356 25 1:94 Perpetual Help College of Pangasinan 642 40 1:16 Polytechnic College of La union 1,101 46 1:24 Philippine College of Science and Technology 1,745 85 1:21 PIMSAT Colleges-Dagupan 1,511 40 1:38 Saint Columban's College 90 11 1:8 Saint Louis College-City of San Fernando 3,385 132 1:26 Saint Mary's College Sta.