Performing Displacements and Rephrasing Attachments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Redacted for Privacy

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Ian B. Edwards for the degree of Master of Arts in Applied Anthropology presented on April 30. 2003. Title: The Fetish Market and Animal Parts Trade of Mali. West Africa: An Ethnographic Investigation into Cultural Use and Significance. Abstract approved: Redacted for Privacy David While much research has examined the intricate interactions associated with the harvesting of wild animals for human consumption, little work has been undertaken in attempting to understand the greater socio-cultural significance of such use. In addition, to properly understand such systems of interaction, an intimate knowledge is required with regard to the rationale or motivation of resource users. In present day Mali, West Africa, the population perceives and upholds wildlife as a resource not only of valuable animal protein, in a region of famine and drought, but a means of generating income. The animal parts trade is but one mechanism within the larger socio-cultural structure that exploits wildlife through a complex human-environmental system to the benefit of those who participate. Moreover, this informal, yet highly structured system serves both cultural and outsider demand through its goods and services. By using traditional ethnographic investigation techniques (participant observation and semi-structured interviews) in combination with thick narration and multidisciplinary analysis (socio- cultural and biological-environmental), it is possible to construct a better understanding of the functions, processes, and motivation of those who participate. In a world where there is butonlya limited supply of natural and wild resources, understanding human- environmental systems is of critical value. ©Copyright by Ian B. -

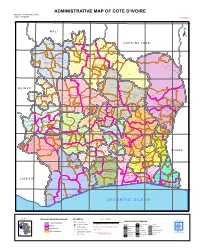

The Crisis in Côte D'ivoire Justin Vaïsse, the Brookings Institution

THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION 1775 Massachusetts Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20036-2188 Tel: 202-797-6000 Fax: 202-797-6004 Divi www.brookings.edu U.S.-FRANCE ANALYSIS SERIES March 2003 The Crisis in Côte d'Ivoire Justin Vaïsse, The Brookings Institution For nearly thirty years after its independence from France in 1960, Côte d'Ivoire presented a rare example of growth and stability in the often-troubled region of West Africa. Now, after fifteen years of economic downturn and three years of political turmoil, Côte d'Ivoire is in the midst of a full-fledged crisis. A new phase of the crisis began in September 2002 when a mutiny erupted in the administrative capital of Abidjan, while rebels in the north seized the cities of Bouaké and Korhogo. They eventually took control of the entire northern part of the country and have the potential, if unsatisfied by political progress, to someday march on Abidjan. (See map). France, the former colonial power, sent reinforcements for the 600 French troops already present in the country under a permanent defense agreement to help protect western African populations and to monitor a cease-fire between the rebels and the government. Center on the United For more briefs in the U.S.-France Analysis Series, see States and France http://www.brookings.edu/usfrance/analysis/index.htm In January 2003, the French government organized peace talks between the Ivorian government, the rebel groups and all political parties, resulting in the Marcoussis Agreements.1 These agreements call for a “reconciliation government” that would include rebels under the leadership of a new prime minister and for the settlement of long-standing issues including access to Ivorian nationality, rules of eligibility and land ownership. -

La Vague De Vandalisme Sur Velospot Touche Aussi Le

FRANC FORT Un fonds alimenté par la BNS contre le chômage? PAGES 7 ET 19 <wm>10CAsNsjY0MDQ20jUytzQ0MwIAkRYDoQ8AAAA=</wm> <wm>10CFXKqw6AMBBE0S_aZmZLty0rSV2DIPgagub_FQ-HuMkVp3dPAV9LW_e2OcGoornS1KkMpTozAoqDSAraTGOlRuNPS8mAAuM1AgrSeIZFIsZkGq7jvAGd4s1zcAAAAA==</wm> 30 EN JANVIER OFFRES Sur toutes les Capsules 2 nouvelles variétés 0 lasemeuse.ch SAMEDI 9 JANVIER 2016 | www.arcinfo.ch | N 6 | CHF 2.70 | J.A. - 2002 NEUCHÂTEL PUBLICITÉ Pour loger «ses» requérants, Neuchâtel fera appel au privé AFFLUX La Suisse fait face au plus grand NEUCHÂTEL Le canton a fait face PROVISOIRE Le canton envisage de louer afflux de réfugiés depuis la guerre aux besoins du premier accueil en ouvrant des lieux capables d’accueillir au Kosovo. Les capacités d’accueil ordinaires des abris PC et en louant des chambres des requérants pour un temps suffisamment sont débordées. d’hôtel. Un «bricolage» qui a ses limites. long et pouvoir fermer les abris PC. PAGE 3 La vague de vandalisme sur Velospot touche aussi le Bas ARCHIVES CHRISTIAN GALLEY CHRISTIAN ARCHIVES MAISON DE L’ABSINTHE Les visites de groupes désertent les distilleries PAGE 7 CABINETS MÉDICAUX Une solution transitoire à la fin du moratoire? PAGE 16 DJIHADISME Trois touristes blessés à l’arme blanche en Egypte PAGE 17 LA MÉTÉO DU JOUR pied du Jura à 1000m 6° 8° 3° 6° DAVID MARCHON LITTORAL Après Bienne et La Chaux-de-Fonds, une vague de vandalisme sur les vélos en libre-service SOMMAIRE a aussi déferlé sur le Littoral. Une soixantaine de petites reines ont vu leur cadenas fracassé Cinéma PAGE 11 Feuilleton PAGE 20 avant d’être abandonnés dans la nature. Un nouveau système de verrou doit être mis en place. -

Région Du GONTOUGO

RAPPORT DE SYNTHESE DU CONTROLE INOPINÉ DE LA QUALITÉ DE SERVICE (QoS) DES RÉSEAUX DE TÉLÉPHONIE MOBILE DANS LA REGION DU GONTOUGOU Du 14/06 au 14/09/2019 |www.valsch-consulting.com TABLE DES MATIERES CHAPITRE 1: CONTEXTE ET GENERALITES ................................................................................................ 3 1.1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................ 4 1.1.1 Contexte ...................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1.2 Objectifs de la mission .................................................................................................................. 4 1.1.3 Périmètre de la mission ................................................................................................................ 5 1.1.4 Services à auditer ......................................................................................................................... 7 1.2 Protocole de mesure et seuil de référence .................................................................................... 7 1.2.1 Evaluation du niveau de champs radioélectrique .......................................................................... 7 1.2.2 Evaluation du service voix en intra réseau ..................................................................................... 9 1.2.3 Evaluation de la qualité du service SMS ..................................................................................... -

Côte D'ivoire Country Focus

European Asylum Support Office Côte d’Ivoire Country Focus Country of Origin Information Report June 2019 SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION European Asylum Support Office Côte d’Ivoire Country Focus Country of Origin Information Report June 2019 More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). ISBN: 978-92-9476-993-0 doi: 10.2847/055205 © European Asylum Support Office (EASO) 2019 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, unless otherwise stated. For third-party materials reproduced in this publication, reference is made to the copyrights statements of the respective third parties. Cover photo: © Mariam Dembélé, Abidjan (December 2016) CÔTE D’IVOIRE: COUNTRY FOCUS - EASO COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION REPORT — 3 Acknowledgements EASO acknowledges as the co-drafters of this report: Italy, Ministry of the Interior, National Commission for the Right of Asylum, International and EU Affairs, COI unit Switzerland, State Secretariat for Migration (SEM), Division Analysis The following departments reviewed this report, together with EASO: France, Office Français de Protection des Réfugiés et Apatrides (OFPRA), Division de l'Information, de la Documentation et des Recherches (DIDR) Norway, Landinfo The Netherlands, Immigration and Naturalisation Service, Office for Country of Origin Information and Language Analysis (OCILA) Dr Marie Miran-Guyon, Lecturer at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (EHESS), researcher, and author of numerous publications on the country reviewed this report. It must be noted that the review carried out by the mentioned departments, experts or organisations contributes to the overall quality of the report, but does not necessarily imply their formal endorsement of the final report, which is the full responsibility of EASO. -

Congrès AFSP 2009 Section Thématique 44 Sociologie Et Histoire Des Mécanismes De Dépacification Du Jeu Politique

Congrès AFSP 2009 Section thématique 44 Sociologie et histoire des mécanismes de dépacification du jeu politique Axe 3 Boris Gobille (ENS-LSH / Université de Lyon / Laboratoire Triangle) [email protected] Comment la stabilité politique se défait-elle ? La fabrique de la dépacification en Côte d’Ivoire, 1990-2000 Le diable gît dans les détails. Il arrive dans les conjonctures de crise politique que les luttes pour la définition des enjeux et pour la maîtrise de la direction à donner à l’incertitude politique en viennent à se synthétiser en un combat de mots. C’est ce qui se produit en Côte d’Ivoire l’été 2000, lorsque partis, presse et « société civile » s’agitent de façon virulente autour de deux conjonctions de coordination : le « et » et le « ou ». Le débat a pris une telle ampleur que la presse satirique s’en empare à son tour, maniant ironiquement le « ni ni » et le « jamais jamais ». Il ne s’agit évidemment pas de grammaire, mais de l’établissement, dans la nouvelle Constitution alors en discussion et appelée à faire l’objet d’un référendum, des conditions d’éligibilité aux élections générales, présidentielle et législatives, qui doivent se tenir à l’automne 2000 et qui sont censées clore la « transition » militaire ouverte par le coup d’Etat du 24 décembre 1999. Doit-on considérer que pour pouvoir candidater il faut être Ivoirien né de père « et » de mère eux-mêmes Ivoiriens, ou bien Ivoirien né de père « ou » de mère ivoirien ? Nul n’est alors dupe, dans ce débat, quant aux implications de la conjonction de coordination qui sera finalement choisie. -

Imams of Gonja the Kamaghate and the Transmission of Islam to the Volta Basin Les Imams De Gonja Et Kamaghate Et La Transmission De L’Islam Dans Le Bassin De La Volta

Cahiers d’études africaines 205 | 2012 Varia Imams of Gonja The Kamaghate and the Transmission of Islam to the Volta Basin Les imams de Gonja et Kamaghate et la transmission de l’islam dans le bassin de la Volta Andreas Walter Massing Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/etudesafricaines/16965 DOI: 10.4000/etudesafricaines.16965 ISSN: 1777-5353 Publisher Éditions de l’EHESS Printed version Date of publication: 15 March 2012 Number of pages: 57-101 ISBN: 978-2-7132-2348-8 ISSN: 0008-0055 Electronic reference Andreas Walter Massing, “Imams of Gonja”, Cahiers d’études africaines [Online], 205 | 2012, Online since 03 April 2014, connection on 03 May 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/etudesafricaines/ 16965 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/etudesafricaines.16965 © Cahiers d’Études africaines Andreas Walter Massing Imams of Gonja The Kamaghate and the Transmission of Islam to the Volta Basin With this article I will illustrate the expansion of a network of Muslim lineages which has played a prominent role in the peaceful spread of Islam in West Africa and forms part of the Diakhanke tradition of al-Haji Salim Suware from Dia1. While the western branch of the Diakhanke in Senegambia and Guinea has received much attention from researchers2, the southern branch of mori lineages with their imamates extending from Dia/Djenne up the river Bani and its branches have been almost ignored. It has established centres of learning along the major southern trade routes and in the Sassandra- Bandama-Comoë-Volta river basins up to the Akan frontier3. The Kamaghate imamate has been established with the Gonja in the Volta basin but can be traced back to the Jula/Soninke of Begho, Kong, Samatiguila, Odienne and ultimately to the region of Djenne and Dia. -

ADMINISTRATIVE MAP of COTE D'ivoire Map Nº: 01-000-June-2005 COTE D'ivoire 2Nd Edition

ADMINISTRATIVE MAP OF COTE D'IVOIRE Map Nº: 01-000-June-2005 COTE D'IVOIRE 2nd Edition 8°0'0"W 7°0'0"W 6°0'0"W 5°0'0"W 4°0'0"W 3°0'0"W 11°0'0"N 11°0'0"N M A L I Papara Débété ! !. Zanasso ! Diamankani ! TENGRELA [! ± San Koronani Kimbirila-Nord ! Toumoukoro Kanakono ! ! ! ! ! !. Ouelli Lomara Ouamélhoro Bolona ! ! Mahandiana-Sokourani Tienko ! ! B U R K I N A F A S O !. Kouban Bougou ! Blésségué ! Sokoro ! Niéllé Tahara Tiogo !. ! ! Katogo Mahalé ! ! ! Solognougo Ouara Diawala Tienny ! Tiorotiérié ! ! !. Kaouara Sananférédougou ! ! Sanhala Sandrégué Nambingué Goulia ! ! ! 10°0'0"N Tindara Minigan !. ! Kaloa !. ! M'Bengué N'dénou !. ! Ouangolodougou 10°0'0"N !. ! Tounvré Baya Fengolo ! ! Poungbé !. Kouto ! Samantiguila Kaniasso Monogo Nakélé ! ! Mamougoula ! !. !. ! Manadoun Kouroumba !.Gbon !.Kasséré Katiali ! ! ! !. Banankoro ! Landiougou Pitiengomon Doropo Dabadougou-Mafélé !. Kolia ! Tougbo Gogo ! Kimbirila Sud Nambonkaha ! ! ! ! Dembasso ! Tiasso DENGUELE REGION ! Samango ! SAVANES REGION ! ! Danoa Ngoloblasso Fononvogo ! Siansoba Taoura ! SODEFEL Varalé ! Nganon ! ! ! Madiani Niofouin Niofouin Gbéléban !. !. Village A Nyamoin !. Dabadougou Sinémentiali ! FERKESSEDOUGOU Téhini ! ! Koni ! Lafokpokaha !. Angai Tiémé ! ! [! Ouango-Fitini ! Lataha !. Village B ! !. Bodonon ! ! Seydougou ODIENNE BOUNDIALI Ponondougou Nangakaha ! ! Sokoro 1 Kokoun [! ! ! M'bengué-Bougou !. ! Séguétiélé ! Nangoukaha Balékaha /" Siempurgo ! ! Village C !. ! ! Koumbala Lingoho ! Bouko Koumbolokoro Nazinékaha Kounzié ! ! KORHOGO Nongotiénékaha Togoniéré ! Sirana -

Pdf Liste Totale Des Chansons

40ú Comórtas Amhrán Eoraifíse 1995 Finale - Le samedi 13 mai 1995 à Dublin - Présenté par : Mary Kennedy Sama (Seule) 1 - Pologne par Justyna Steczkowska 15 points / 18e Auteur : Wojciech Waglewski / Compositeurs : Mateusz Pospiezalski, Wojciech Waglewski Dreamin' (Révant) 2 - Irlande par Eddie Friel 44 points / 14e Auteurs/Compositeurs : Richard Abott, Barry Woods Verliebt in dich (Amoureux de toi) 3 - Allemagne par Stone Und Stone 1 point / 23e Auteur/Compositeur : Cheyenne Stone Dvadeset i prvi vijek (Vingt-et-unième siècle) 4 - Bosnie-Herzégovine par Tavorin Popovic 14 points / 19e Auteurs/Compositeurs : Zlatan Fazlić, Sinan Alimanović Nocturne 5 - Norvège par Secret Garden 148 points / 1er Auteur : Petter Skavlan / Compositeur : Rolf Løvland Колыбельная для вулкана - Kolybelnaya dlya vulkana - (Berceuse pour un volcan) 6 - Russie par Philipp Kirkorov 17 points / 17e Auteur : Igor Bershadsky / Compositeur : Ilya Reznyk Núna (Maintenant) 7 - Islande par Bo Halldarsson 31 points / 15e Auteur : Jón Örn Marinósson / Compositeurs : Ed Welch, Björgvin Halldarsson Die welt dreht sich verkehrt (Le monde tourne sens dessus dessous) 8 - Autriche par Stella Jones 67 points / 13e Auteur/Compositeur : Micha Krausz Vuelve conmigo (Reviens vers moi) 9 - Espagne par Anabel Conde 119 points / 2e Auteur/Compositeur : José Maria Purón Sev ! (Aime !) 10 - Turquie par Arzu Ece 21 points / 16e Auteur : Zenep Talu Kursuncu / Compositeur : Melih Kibar Nostalgija (Nostalgie) 11 - Croatie par Magazin & Lidija Horvat 91 points / 6e Auteur : Vjekoslava Huljić -

Region Du Gontougo

REPUBLIQUE DE COTE D’IVOIRE Union-Discipline-Travail MINISTERE DE L’EDUCATION NATIONALE Statistiques Scolaires de Poche 2015-2016 REGION DU GONTOUGO Sommaire Sommaire ................................................................................................. 2 Sigles et Abréviations ................................................................................ 3 Méthodologie ........................................................................................... 4 Introduction .............................................................................................. 5 1 / Résultats du Préscolaire 2015-2016 ....................................................... 7 1-1 / Chiffres du Préscolaire en 2015-2016 ............................................. 8 1-2 / Indicateurs du Préscolaire en 2015-2016 ...................................... 14 1-3 / Préscolaire dans les Sous-préfectures en 2015-2016 .................... 15 2 / Résultats du Primaire 2015-2016 ......................................................... 20 2-1 / Chiffres du Primaire en 2015-2016 ................................................ 21 2-2 / Indicateurs du Primaire en 2015-2016 .......................................... 32 2-3 / Primaire dans les Sous-préfectures en 2015-2016 ......................... 35 3/ Résultats du Secondaire Général en 2015-2016 ..................................... 41 3-1 / Chiffres du Secondaire Général en 2015-2016 ................................ 42 3-2 / Indicateurs du Secondaire Général en 2015-2016.......................... -

“The Best School” RIGHTS Student Violence, Impunity, and the Crisis in Côte D’Ivoire WATCH

Côte d’Ivoire HUMAN “The Best School” RIGHTS Student Violence, Impunity, and the Crisis in Côte d’Ivoire WATCH “The Best School” Student Violence, Impunity, and the Crisis in Côte d’Ivoire Copyright © 2008 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-312-9 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org May 2008 1-56432-312-9 “The Best School” Student Violence, Impunity, and the Crisis in Côte d’Ivoire Map of Côte d’Ivoire ...........................................................................................................2 Glossary of Acronyms......................................................................................................... 3 Summary ...........................................................................................................................6 -

Eurovision Karaoke

1 Eurovision Karaoke ALBANÍA ASERBAÍDJAN ALB 06 Zjarr e ftohtë AZE 08 Day after day ALB 07 Hear My Plea AZE 09 Always ALB 10 It's All About You AZE 14 Start The Fire ALB 12 Suus AZE 15 Hour of the Wolf ALB 13 Identitet AZE 16 Miracle ALB 14 Hersi - One Night's Anger ALB 15 I’m Alive AUSTURRÍKI ALB 16 Fairytale AUT 89 Nur ein Lied ANDORRA AUT 90 Keine Mauern mehr AUT 04 Du bist AND 07 Salvem el món AUT 07 Get a life - get alive AUT 11 The Secret Is Love ARMENÍA AUT 12 Woki Mit Deim Popo AUT 13 Shine ARM 07 Anytime you need AUT 14 Conchita Wurst- Rise Like a Phoenix ARM 08 Qele Qele AUT 15 I Am Yours ARM 09 Nor Par (Jan Jan) AUT 16 Loin d’Ici ARM 10 Apricot Stone ARM 11 Boom Boom ÁSTRALÍA ARM 13 Lonely Planet AUS 15 Tonight Again ARM 14 Aram Mp3- Not Alone AUS 16 Sound of Silence ARM 15 Face the Shadow ARM 16 LoveWave 2 Eurovision Karaoke BELGÍA UKI 10 That Sounds Good To Me UKI 11 I Can BEL 86 J'aime la vie UKI 12 Love Will Set You Free BEL 87 Soldiers of love UKI 13 Believe in Me BEL 89 Door de wind UKI 14 Molly- Children of the Universe BEL 98 Dis oui UKI 15 Still in Love with You BEL 06 Je t'adore UKI 16 You’re Not Alone BEL 12 Would You? BEL 15 Rhythm Inside BÚLGARÍA BEL 16 What’s the Pressure BUL 05 Lorraine BOSNÍA OG HERSEGÓVÍNA BUL 07 Water BUL 12 Love Unlimited BOS 99 Putnici BUL 13 Samo Shampioni BOS 06 Lejla BUL 16 If Love Was a Crime BOS 07 Rijeka bez imena BOS 08 D Pokušaj DUET VERSION DANMÖRK BOS 08 S Pokušaj BOS 11 Love In Rewind DEN 97 Stemmen i mit liv BOS 12 Korake Ti Znam DEN 00 Fly on the wings of love BOS 16 Ljubav Je DEN 06 Twist of love DEN 07 Drama queen BRETLAND DEN 10 New Tomorrow DEN 12 Should've Known Better UKI 83 I'm never giving up DEN 13 Only Teardrops UKI 96 Ooh aah..