Meeting Daria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MAGGIE MUGGINS to Mcqueen

MAGGIE MUGGINS to McQUEEN Maggie Muggins Thu 4:45-5:00 p.m., 29 Sep 1955-28 Jun 1956 Thu 5:00-5:15 p.m., 4 Oct 1956-27 Jun 1957 Thu 5:00-5:15 p.m., 3 Oct 1957-26 Jun 1958 Thu 4:30-4:45 p.m., 16 Oct 1958-25 Jun 1959 Tue 4:45-5:00 p.m., 13 Oct 1959-21 Jun 1960 Tue 4:30-4:45 p.m., 18 Oct 1960-26 Sep 1961 Wed 3:45-4:00 p.m., 4 Oct-27 Dec 1961 Wed 4:45-5:00 p.m., 3 Jan-27 Jun 1962 Writer Mary Grannan created Maggie Muggins, a freckle-faced girl in a gingham dress, with her red hair pulled back in two long pigtails. Her stories had been heard on CBC radio and in print for years (See New Maggie Muggins Stories: A Selection of the Famous Radio Stories. Toronto: Thomas Allen, 1947) before Maggie and her friends in the meadow materialized on television in 1955. In the popular, fifteen minute broadcast, Maggie played with friends like Fitzgerald Fieldmouse and Grandmother Frog. When she was caught in a quandary, her neighbour, Mr. McGarrity, usually to be found in checked shirt, straw hat and bib overalls, working in his garden, gave her advice or tried to help her to understand whatever was bothering her. When she was bored or tired, he might tell her a story or cheer her up by leading a song. Along with these principal characters, the meadow was filled with other animal friends, some of whom fit the pastoral setting, others who seemed a little out of place; Reuben Rabbit, Big Bite Beaver, Chester Pig, Greta Grub, Benny Bear, Leo Lion, Henrietta Hen, and Fluffy Squirrel. -

Uot History Freidland.Pdf

Notes for The University of Toronto A History Martin L. Friedland UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO PRESS Toronto Buffalo London © University of Toronto Press Incorporated 2002 Toronto Buffalo London Printed in Canada ISBN 0-8020-8526-1 National Library of Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data Friedland, M.L. (Martin Lawrence), 1932– Notes for The University of Toronto : a history ISBN 0-8020-8526-1 1. University of Toronto – History – Bibliography. I. Title. LE3.T52F75 2002 Suppl. 378.7139’541 C2002-900419-5 University of Toronto Press acknowledges the financial assistance to its publishing program of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council. This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Humanities and Social Sciences Federation of Canada, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. University of Toronto Press acknowledges the finacial support for its publishing activities of the Government of Canada, through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program (BPIDP). Contents CHAPTER 1 – 1826 – A CHARTER FOR KING’S COLLEGE ..... ............................................. 7 CHAPTER 2 – 1842 – LAYING THE CORNERSTONE ..... ..................................................... 13 CHAPTER 3 – 1849 – THE CREATION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO AND TRINITY COLLEGE ............................................................................................... 19 CHAPTER 4 – 1850 – STARTING OVER ..... .......................................................................... -

Eric Koch Fonds Inventory #472

page 1 Eric Koch fonds Inventory #472 File: Title: Date(s): Note: Call Number: 2004-047/001 (1) Essays/Articles about Koch 1978,1999-2004 (2) Early Fiction, Drafts 1944-1949 (3) Eric Koch, Short CV and Related Biographical 1997-2003 Information (4) Public Archives of Canada/Canada Council, 1980-1987 Correspondence Writing Files (5) The Globe and Mail, Articles/Reviews by Koch 1981-1999 (6) Saturday Night Articles 1944-1945 (7) Attempts, Includes Drafts and Correspondence with 1959-1987 1 of 2 Publishers (8) Attempts, Includes Drafts and Correspondence with 1959-1987 2 of 2 Publishers (9) The French Kiss, Correspondence 1964-1972 1 of 2 (10) The French Kiss, Correspondence 1964-1972 2 of 2 (11) The French Kiss, Clippings, Reviews 1969-2000 (12) Bonhomme the Sixteenth, Correspondence 1969-1972 (13) The Leisure Riots, Publicity 1973 (14) The Leisure Riots, Post Publication Correspondence 1973-1974 Call Number: 2004-047/002 (1) The Leisure Riots, Fan Letters 1973-1975 (2) The Leisure Riots, Contracts, Business Letters 1973-1978 (3) The Leisure Riots, Reviews 1973 (4) Last Thing, Tundra 1975-1978 (5) Last Thing, Reviews, American 1976 (6) Last Thing, Reviews, American 1976 (7) Last Thing, Early Attempts (8) Last Thing, Scribner's 1976 (9) Last Thing, Fan Mail, Post Publication Correspondence, 1976-1977 misc (10) Heyne, German Publisher of Leisure Riots and Last 1987-1988 Thing, Correspondence (11) Good Night Little Spy, Ram Publishing 1979 (12) Good Night Little Spy, Publicity 1979 (13) Good Night Little Spy 1979-1982 (14) Good Night Little Spy 1979 (15) Deemed Suspect, Reviews 1980-1984 (16) Deemed Suspect, Methuen 1979-1984 page 2 Eric Koch fonds Inventory #472 File: Title: Date(s): Note: (17) Deemed Suspect, Montreal Anniversary 1980 (18) Deemed Suspect, Correspondence 1981-1985 1 of 2 (19) Deemed Suspect, Correspondence 1981-1985 2 of 2 (20) Deemed Suspect, Maclean's Magazine 10 Feb. -

War on the Air: CBC-TV and Canada's Military, 1952-1992 by Mallory

War on the Air: CBC-TV and Canada’s Military, 19521992 by Mallory Schwartz Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctorate in Philosophy degree in History Department of History Faculty of Arts University of Ottawa © Mallory Schwartz, Ottawa, Canada, 2014 ii Abstract War on the Air: CBC-TV and Canada‘s Military, 19521992 Author: Mallory Schwartz Supervisor: Jeffrey A. Keshen From the earliest days of English-language Canadian Broadcasting Corporation television (CBC-TV), the military has been regularly featured on the news, public affairs, documentary, and drama programs. Little has been done to study these programs, despite calls for more research and many decades of work on the methods for the historical analysis of television. In addressing this gap, this thesis explores: how media representations of the military on CBC-TV (commemorative, history, public affairs and news programs) changed over time; what accounted for those changes; what they revealed about CBC-TV; and what they suggested about the way the military and its relationship with CBC-TV evolved. Through a material culture analysis of 245 programs/series about the Canadian military, veterans and defence issues that aired on CBC-TV over a 40-year period, beginning with its establishment in 1952, this thesis argues that the conditions surrounding each production were affected by a variety of factors, namely: (1) technology; (2) foreign broadcasters; (3) foreign sources of news; (4) the influence -

Creativity, Community, and Memory Building: Interned Jewish Refugees in Canada During and After World War II

Creativity, Community, and Memory Building: Interned Jewish Refugees in Canada During and After World War II By Elise Bigley A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History with Specialization in Digital Humanities Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario ©2017 Elise Bigley ii Abstract In May of 1940, a wartime British government arrested those deemed “enemy aliens” and transferred them to safe areas of the country. Over 2000 of these “enemy aliens” were Jewish German and Austrian men. On June 29, 1940, the first group of Jewish refugees was sent to internment camps in Canada. This thesis explores three different examples of memory and community to illustrate the development of the internees’ search for meaning during and post-internment. Artwork created in the camps, a series of letters between ex-internees, and several issues of the Ex-Internees Newsletter are the focus of this study. Social network analysis tools are used to visualize the post- internment internee network. By looking at diverse aspects of the internment narrative, this thesis provides a unique lens into the conversation on memory and history. iii Acknowledgments I would like to express my deep gratitude to my co-supervisors Dr. John C. Walsh and Dr. James Opp for their useful comments, remarks, and engagement during the past two years. A special thanks to John for accepting all of my work past the many ‘deadlines’ I set for myself. This thesis would not have been possible without the expertise of Dr. -

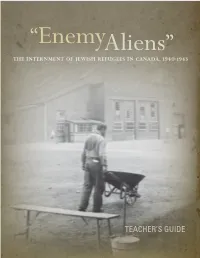

Complete Teachers' Guide to Enemy

“EnemyAliens” The Internment of Jewish Refugees in Canada, 1940-1943 TEACHER’S GUIDE “ENEMY ALIENS”: The Internment of Jewish Refugees in Canada, 1940-1943 © 2012, Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre Lessons: Nina Krieger Text: Paula Draper Research: Katie Powell, Katie Renaud, Laura Mehes Translation: Myriam Fontaine Design: Kazuko Kusumoto Copy Editing: Rome Fox, Anna Migicovsky Cover image: Photograph of an internee in a camp uniform, taken by internee Marcell Seidler, Camp N (Sherbrooke, Quebec), 1940-1942. Seidler secretly documented camp life using a handmade pinhole camera. − Courtesy Eric Koch / Library and Archives Canada / PA-143492 Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre 50 - 950 West 41st Avenue Vancouver, BC V5Z 2N7 604 264 0499 / [email protected] / www.vhec.org Material may be reproduced for non-commercial purposes provided that the publisher and author are acknowledged. The exhibit Enemy Aliens: The Internment of Jewish Refugees in Canada, 1940 – 1943 was generously funded by the Community Historical Recognition Program of the Department of Citizenship, Immigration and Multiculturalism Canada. With the generous support of: Oasis Foundation The Ben and Esther Dayson Charitable Foundation The Kahn Family Foundation Isaac and Sophie Waldman Endowment Fund of the Vancouver Foundation Frank Koller The Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre gratefully acknowledges the financial investment by the Department of Canadian Heritage in the creation of this online presentation for the Virtual Museum of Canada. Teacher’s Guide made possible through the generous support of the Mordehai and Hana Wosk Family Endowment Fund of the Vancouver Holocaust Centre Society. With special thanks to the former internees and their families, who generously shared their experiences and artefacts in the creation of the exhibit. -

The Russian Revolution of 1905-1907 Public Speeches

Morris “forbade me to make any more The Russian Revolution of 1905-1907 public speeches. But…the sailors and workers,” he said, “responded to the colo- evolution across the Russian Em- nel’s order by a written protest bearing five pire was sparked in 1905, when hundred and thirty signatures.”23 RCzarist troops shot and killed a Trotsky also reminisced that: thousand or more peaceful protesters in St. “prisoners gave us a most impressive Petersburg. In the Russian, Polish, Ukrain- send-off,….sailors and workers lined ian, Finnish, Latvian and Estonian protests the passage..., an improvised band that followed this “Bloody Sunday” mas- played the revolutionary march, and sacre, millions joined general strikes and friendly hands were extended to us from mass rallies. To crush this struggle for jus- every quarter. One of the prisoners de- tice, democracy and labour rights, impe- livered a short speech acclaiming the Russian revolution and cursing the Ger- rial troops killed thousands of socialists man monarchy. Even now it makes me and anarchists, and interned some 300,000. happy to remember that in the very In 1909, Britain’s Parliamentary Peter midst of the war, we were fraternizing Russian Committee, which included an with German sailors in Amherst.”24 Anglican Bishop and two dozen MPs, pub- In 1909, this exiled Russian scientist, The Amherst camp did not close lished The Terror in Russia, by Peter Kro- atheist and anarcho-communist reported until September 27, 1919, almost a year potkin, a Russian geographer, economist, on the Csarist imperial regime’s brutal after WWI ended. Other Canadian prison atheist, evolutionary theorist and anarcho- repression of strikes and mass protests. -

Captured Lives

Martin Auger. Prisoners on the Home Front: German POWs and "Enemy Aliens" in Southern Quebec, 1940-1946. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2005. 240 pp. $35.95, paper, ISBN 978-0-7748-1224-5. Reviewed by Angelika E. Sauer Published on H-Canada (January, 2007) Concentration camps had come a long way excellent bibliography of published and unpub‐ since the turn of the century, when Western colo‐ lished secondary sources, integrating them into nial powers (notably Spain, the United States, and his narrative without, however, fully positioning Britain) frst started herding civilians into con‐ himself in the historiography of internment. His fined spaces in an attempt to subjugate hostile main point is that "the internment operation in populations in their overseas colonies. By the time Canada, although occasionally lacking proper or‐ Canada received its frst batch of mostly German ganization, was a positive experience overall"--a Jewish civilian internees from Britain in 1940, es‐ home front victory (pp .4, 152). Other writers have tablishing internment operations "had become questioned the legality of interning civilians and standard procedure in times of war," as Martin the positive experience that internment allegedly Auger assures us (p. 18). All belligerents used provided.[1] But Auger's point is well taken: one camps to intern not only prisoners of war but also should not, even in a casual way, equate Canada's to neutralize potential internal enemies. Designed internment camps with Nazi Germany's concen‐ by the modern state and managed by a special‐ tration camps. Growing out of the same seed of ized bureaucracy, these modernized internment extending colonial warfare to perceived civilian operations could range from the horrors of the enemies, these two types of camps had historical‐ Nazi concentration camps, Stalinist gulags, and Ja‐ ly become very different and nearly unrelated panese torture camps to the fair and humane phenomena. -

Foreign Rights 200708.Indd

mosaic press Foreign rights 2007-2008 Canada 1252 Speers Road Units 1 & 2 Oakville, Ontario L6L 5N9 Ph/Fax 905.825.2130 U.S.A. PMB 145, 4500 Witmer Industrial Estates Niagara Falls, NY 14305-1386 Ph/Fax 1.800.387.8992 www.mosaic-press.com [email protected] mosaic presswww.mosaic-press.com Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra Programs and Concert Posters 1882-2006 160 pages, full colour Famous conductors, illustrious soloists, a legacy of outstanding performances; this coffee table-sized gift book will be produced in a bilingual English-German edition, indispensable for the Philharmonic fan, a treat for every music lover, and a beautiful testament to a fascinating history. Just some of the highlights: * 1884. The Berlin Philharmonic performs Johannes Brahms’ 3rd Symphony under the baton of the composer. * 1895. The world premiere of Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No.2 ‘Resurrection’, with the Berlin Philharmonic, conducted by Gustav Mahler. * 1902. On one Berlin Philharmonic program, Jean Sibelius, Hans Pfitzner and Ferruccio Busoni conduct their own compositions. * 1932. Wilhelm Furtwängler conducts the Berlin Philharmonic in Prokofiev’s 3rd Piano Concerto with the composer at the piano, followed by Berlioz’s Harold in Italy, viola soloist: Paul Hindemith. * 1936. Before an audience of 5 000 at Berlin’s Deutschlandhalle, Richard Strauss leads the Berlin Philharmonic in the music of Richard Strauss. * 1955. The Berlin Philharmonic’s first tour to North America with their new Music Director, Herbert von Karajan. * 1966. Inauguration of the Salzburg Easter Festival, Wagner’s Die Walküre, with the Berlin Philharmonic in the pit. * 1976. The Berlin Philharmonic plays Mozart at the Tehran Arts Festival, Iran. -

This Half Hour

TGIF to THIS HALF HOUR TGIF Fri 2:30-3:00 p.m., 5 Jan-11 May 1973 Fri 2:30-3:00 p.m., 5 Oct 1973-29 Mar 1974 A production of CBLT and circulated in the Ontario region, T.G.I.F. included interviews, reports on local activities, and suggestions for the weekend in the Toronto area. The show featured hosts for each day of the weekend, including announcer Alex Trebek, the program's producer Agota Gabor, and cartoonist Ben Wicks. Regulars also included Doug Lennox, Sol Littman on art, Brenna Brown on restaurants and dining, and Harold Town on movies. The executive producer was Dodi Robb. Tabloid Mon-Sat 7:00-7:30 p.m., 9 Mar 1953-26 Jun 1954 Mon-Fri 6:30-7:00 p.m., 6 Sep 1954- Mon-Fri 7:00-7:30 p.m., 3 Jul 1955-31 Sep 1960 Tabloid was the eclectic half-hour of news, public affairs, and interviews pioneered by producer Ross McLean at Toronto's CBLT. It also established the tendency of Canadian television to draw its stars from news programming as much as from variety or dramatic programs. The host of the show was Dick MacDougal, a veteran radio host with a portly figure, basset hound eyes, and an affable manner. The first live human being to appear on CBC television in Toronto, the lean, bespectacled, and garrulous Percy Saltzman had forecast the weather on Let's See before McLean moved him from the puppet show to Tabloid. Saltzman, a meteorologist with the Dominion Weather Service, had started a parallel, second career in writing and broadcasting for radio in 1948, and since developed a healthy following among listeners and television viewers. -

Spring 2018 • May 6, 2018 • 12 P.M

POMP, CIRCUMSTANCE, AND OTHER SONGS OF A LIFETIME POMP, CIRCUMSTANCE, (continued from inside front cover) AND OTHER SONGS OF A LIFETIME —by Professor David Citino, 1947–2005, Late University Poet Laureate I say, rather, the richness of us, were it not for the lullabyes and songs (Originally presented as the 2000 Winter Commencement address) of dear parents, their parents, theirs. of selves that balance this globe Some are here today in the flesh. and enable it to spin true. Grandson Many are not. We mourn them with cadences of peasant immigrants, I was given of our hearts. Think how many people If you’re like me, you’ve got a big head, the opportunity to earn a doctorate sang before us, gave us a name, a voice, not to mention a funny robe, full of music— to do your best. Tennessee Ernie Ford, in English literature from Ohio State— taught us the right words. We must poems and melodies, the tunes “Sixteen Tons”: St. Peter don’t you because my family labored long nights cherish them by remembering every song. we move to, shower and shave by, call me ‘Cause I can’t go. I owe around the kitchen table trying to learn When we sing to others, we honor study, write to. Not just the incidental, my soul to the company store. this arduous English. I sat where our fathers and mothers, thank them but the momentous music keeping time. You have been digging deep in mines you’re sitting twenty-six years ago. for this day of profound scarlet and gray Our histories are measures of song. -

Foreign Rights 2010.Indd

mosaic press Foreign rights 2009-10 Canada 1252 Speers Road Units 1 & 2 Oakville, Ontario L6L 5N9 Ph/Fax 905.825.2130 U.S.A. PMB 145, 4500 Witmer Industrial Estates Niagara Falls, NY 14305-1386 Ph/Fax 1.800.387.8992 www.mosaic-press.com [email protected] mosaic presswww.mosaic-press.com Canada 1252 Speers Road Inside the New Chinese Economy!! Units 1 & 2 Oakville, Ontario L6L 5N9 Ph/Fax 905.825.2130 China Inc. U.S.A. PMB 145, 4500 Witmer Industrial Estates Niagara Falls, New York 36 inside and true stories portraying how Chinese 14305-1386 entrepreneurs made their fortunes in the new Ph/Fax 1.800.387.8992 Chinese economy [email protected] It has been 30 years since the Chinese economy was ‘opened up’. China is now the land of opportunity where vast fortunes are made, where entrepreneurs with drive and talent are revered and fortunes are made. The ‘enterprise’ economy is what moves China on and helps build the economic juggernaut which generates a 10% plus an- nual growth in GDP. How does the system work? How do entrepreneurs operate in the new environ- ment? How do they make money? Who are the members of this new entrepreneurial class? In China Inc. you will meet these people, read their first-hand stories and learn more about what moti- vates them. Available now. Foreign Rights by Mosaic Press Published by New World Press mosaic press mosaic presswww.mosaic-press.com Canada Canada 1252 Speers Road 1252 Speers Road Units 1 & 2 Inside the New Chinese Economy!! Units 1 & 2 Oakville, Ontario Oakville, Ontario L6L 5N9 L6L 5N9 Ph/Fax 905.825.2130 Ph/Fax 905.825.2130 U.S.A.