Toccata Classics TOCC0104 Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET SYMPHONIES Composers

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET SYMPHONIES A Discography of CDs and LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers A-G KHAIRULLO ABDULAYEV (b. 1930, TAJIKISTAN) Born in Kulyab, Tajikistan. He studied composition at the Moscow Conservatory under Anatol Alexandrov. He has composed orchestral, choral, vocal and instrumental works. Sinfonietta in E minor (1964) Veronica Dudarova/Moscow State Symphony Orchestra ( + Poem to Lenin and Khamdamov: Day on a Collective Farm) MELODIYA S10-16331-2 (LP) (1981) LEV ABELIOVICH (1912-1985, BELARUS) Born in Vilnius, Lithuania. He studied at the Warsaw Conservatory and then at the Minsk Conservatory where he studied under Vasily Zolataryov. After graduation from the latter institution, he took further composition courses with Nikolai Miaskovsky at the Moscow Conservatory. He composed orchestral, vocal and chamber works. His other Symphonies are Nos. 1 (1962), 3 in B flat minor (1967) and 4 (1969). Symphony No. 2 in E minor (1964) Valentin Katayev/Byelorussian State Symphony Orchestra ( + Vagner: Suite for Symphony Orchestra) MELODIYA D 024909-10 (LP) (1969) VASIF ADIGEZALOV (1935-2006, AZERBAIJAN) Born in Baku, Azerbaijan. He studied under Kara Karayev at the Azerbaijan Conservatory and then joined the staff of that school. His compositional catalgue covers the entire range of genres from opera to film music and works for folk instruments. Among his orchestral works are 4 Symphonies of which the unrecorded ones are Nos. 1 (1958) and 4 "Segah" (1998). Symphony No. 2 (1968) Boris Khaikin/Moscow Radio Symphony Orchestra (rec. 1968) ( + Piano Concertos Nos. 2 and 3, Poem Exaltation for 2 Pianos and Orchestra, Africa Amidst MusicWeb International Last updated: August 2020 Russian, Soviet & Post-Soviet Symphonies A-G Struggles, Garabagh Shikastasi Oratorio and Land of Fire Oratorio) AZERBAIJAN INTERNATIONAL (3 CDs) (2007) Symphony No. -

International Viola Congress

CONNECTING CULTURES AND GENERATIONS rd 43 International Viola Congress concerts workshops| masterclasses | lectures | viola orchestra Cremona, October 4 - 8, 2016 Calendar of Events Tuesday October 4 8:30 am Competition Registration, Sala Mercanti 4:00 pm Tymendorf-Zamarra Recital, Sala Maffei 9:30 am-12:30 pm Competition Semifinal,Teatro Filo 4:00 pm Stanisławska, Guzowska, Maliszewski 10:00 am Congress Registration, Sala Mercanti Recital, Auditorium 12:30 pm Openinig Ceremony, Auditorium 5:10 pm Bruno Giuranna Lecture-Recital, Auditorium 1:00 pm Russo Rossi Opening Recital, Auditorium 6:10 pm Ettore Causa Recital, Sala Maffei 2:00 pm-5:00 pm Competition Semifinal,Teatro Filo 8:30 pm Competition Final, S.Agostino Church 2:00 pm Dalton Lecture, Sala Maffei Post-concert Café Viola, Locanda il Bissone 3:00 pm AIV General Meeting, Sala Mercanti 5:10 pm Tabea Zimmermann Master Class, Sala Maffei Friday October 7 6:10 pm Alfonso Ghedin Discuss Viola Set-Up, Sala Maffei 9:00 am ESMAE, Sala Maffei 8:30 pm Opening Concert, Auditorium 9:00 am Shore Workshop, Auditorium Post-concert Café Viola, Locanda il Bissone 10:00 am Giallombardo, Kipelainen Recital, Auditorium Wednesday October 5 11:10 am Palmizio Recital, Sala Maffei 12:10 pm Eckert Recital, Sala Maffei 9:00 am Kosmala Workshop, Sala Maffei 9:00 am Cuneo Workshop, Auditorium 12:10 pm Rotterdam/The Hague Recital, Auditorium 10:00 am Alvarez, Richman, Gerling Recital, Sala Maffei 1:00 pm Street Concerts, Various Locations 11:10 am Tabea Zimmermann Recital, Museo del Violino 2:00 pm Viola Orchestra -

Anna Giust Questo Articolo È Dedicato All'opera Passažirka

EUROPA ORIENTALIS 37 (2018) PASSAŽIRKA DI MIECZYSŁAW WEINBERG: OPERA RUSSA E TEMATICA EBRAICA NELLA ‘SCUOLA ŠOSTAKOVICIANA’ Anna Giust Questo articolo è dedicato all’opera Passažirka di Mieczysław Weinberg, compositore sovietico di famiglia ebrea, che fece dell’Olocausto e della guerra una tematica centrale della propria poetica, dedicandovi diverse composizioni. Una produzione vasta – che include opere liriche, un’operetta, balletti, sinfo- nie, quartetti per archi, oltre a una sessantina di partiture per il cinema, sonate, cantate e altri pezzi di minore portata – che in questi anni sta vivendo una ri- scoperta. Nel 2010 proprio Passažirka, che forse rappresenta meglio di ogni altra la scelta ‘morale’ del compositore,1 è andata in scena con successo al Festival di Bregenz (Austria), – una Prima in forma scenica dopo l’unica esecuzione in forma di concerto tenutasi il 25 dicembre 2006 alla Sala Svetlanov del- l’Unione dei Compositori a Mosca, che interrompeva la lunga attesa dal mo- mento della genesi.2 Il 21 novembre 2009 a Liverpool ha avuto luogo la Pri- ma del suo Requiem op. 96, mai eseguito durante la vita dell’autore. Si tratta delle due opere che meglio esprimono la sua denuncia degli orrori dell’Olo- causto e il compianto per le vittime delle perversioni della politica del XX secolo. Dopo la riscoperta di queste composizioni, per anni rimaste inesegui- te, ha avuto inizio il recupero di altre opere dell’autore, un recupero peraltro più attivo in Europa che in Russia.3 In Italia alcuni appuntamenti gli sono _________________ 1 Secondo Ljudmila Nikitina, era lo stesso compositore a considerare quest’opera come il proprio capolavoro: L. -

Cultural Influences Upon Soviet-Era Programmatic Piano Music for Children

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones 5-1-2017 Cultural Influences upon Soviet-Era Programmatic Piano Music for Children Maria Pisarenko University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Education Commons, Fine Arts Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Repository Citation Pisarenko, Maria, "Cultural Influences upon Soviet-Era Programmatic Piano Music for Children" (2017). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 3025. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/10986115 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CULTURAL INFLUENCES UPON SOVIET-ERA PROGRAMMATIC PIANO MUSIC FOR CHILDREN By Maria Pisarenko Associate of Arts – Music Education (Piano Pedagogy/Performance/Collaborative Piano) Irkutsk College of Music, City -

Cello Concerto (1990)

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET CONCERTOS A Discography of CDs and LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Edited by Stephen Ellis Composers A-G RUSTAM ABDULLAYEV (b. 1947, UZBEKISTAN) Born in Khorezm. He studied composition at the Tashkent Conservatory with Rumil Vildanov and Boris Zeidman. He later became a professor of composition and orchestration of the State Conservatory of Uzbekistan as well as chairman of the Composers' Union of Uzbekistan. He has composed prolifically in most genres including opera, orchestral, chamber and vocal works. He has completed 4 additional Concertos for Piano (1991, 1993, 1994, 1995) as well as a Violin Concerto (2009). Piano Concerto No. 1 (1972) Adiba Sharipova (piano)/Z. Khaknazirov/Uzbekistan State Symphony Orchestra ( + Zakirov: Piano Concerto and Yanov-Yanovsky: Piano Concertino) MELODIYA S10 20999 001 (LP) (1984) LEV ABELIOVICH (1912-1985, BELARUS) Born in Vilnius, Lithuania. He studied at the Warsaw Conservatory and then at the Minsk Conservatory where his composition teacher was Vasily Zolataryov. After graduation from the latter institution, he took further composition courses with Nikolai Miaskovsky at the Moscow Conservatory. He composed orchestral, vocal and chamber works. Piano Concerto in E minor (1976) Alexander Tutunov (piano)/ Marlan Carlson/Corvallis-Oregon State University Symphony Orchestra ( + Piano Trio, Aria for Viola and Piano and 10 Romances) ALTARUS 9058 (2003) Aria for Violin and Chamber Orchestra (1973) Mikhail Shtein (violin)/Alexander Polyanko/Minsk Chamber Orchestra ( + Vagner: Clarinet Concerto and Alkhimovich: Concerto Grosso No. 2) MELODIYA S10 27829 003 (LP) (1988) MusicWeb International Last updated: August 2020 Russian, Soviet & Post-Soviet Concertos A-G ISIDOR ACHRON (1891-1948) Piano Concerto No. -

Journal of the American Viola Society Volume 32 No. 1, Spring 2016

Features: Bartolomeo Campagnoli and His 41 Capricci An Afternoon at Skittles: On Playing Mozart’s “Kegelstatt” Trio Part I Volume 32 Number 1 Number 32 Volume Journal of the American ViolaSociety American the of Journal Viola V32 N1.indd 301 3/16/16 6:20 PM Viola V32 N1.indd 302 3/16/16 6:20 PM Journal of the American Viola Society A publication of the American Viola Society Spring 2016: Volume 32, Number 1 p. 3 From the Editor p. 5 From the President News & Notes p. 7 Announcements Feature Articles p. 9 Bartolomeo Campagnoli and His 41 Capricci: The Ever-Changing Role of the Virtuosic Viola and Its Technique: Dalton Competition prize-winner Alicia Marie Valoti explores a history of the Campagnoli 41 Capricci and its impact on the progression of the viola’s reputation as a virtuosic instrument. p. 19 An Afternoon at Skittles: On Playing Mozart’s “Kegelstatt” Trio Part I: A Trio for Signora Dinimininimi, Nàtschibinìtschibi, and Pùnkitititi: Edward Klorman gives readers an interesting look into background on the Mozart “Kegelstatt” Trio. Departments p. 29 New Music: Michael Hall presents a number of exciting new works for viola. p. 35 Outreach: Janet Anthony and Carolyn Desroisers give an account of the positive impact that BLUME is having on music education in Haiti. p. 39 Retrospective: JAVS Associate Editor David M. Bynog writes about the earliest established viola ensemble in the United States. p. 45 Student Life: Zhangyi Chen describes how one of his choral compositions became the basis of a new viola concerto. p. -

International Viola Congress

CONNECTING CULTURES AND GENERATIONS rd 43 International Viola Congress concerts workshops| masterclasses | lectures | viola orchestra Cremona, October 4 - 8, 2016 Calendar of Events Tuesday October 4 8:30 am Competition Registration, Sala Mercanti 4:00 pm Tymendorf-Zamarra Recital, Sala Maffei 9:30 am-12:30 pm Competition Semifinal,Teatro Filo 4:00 pm Stanisławska, Guzowska, Maliszewski 10:00 am Congress Registration, Sala Mercanti Recital, Auditorium 12:30 pm Openinig Ceremony, Auditorium 5:10 pm Bruno Giuranna Lecture-Recital, Auditorium 1:00 pm Russo Rossi Opening Recital, Auditorium 6:10 pm Ettore Causa Recital, Sala Maffei 2:00 pm-5:00 pm Competition Semifinal,Teatro Filo 8:30 pm Competition Final, S.Agostino Church 2:00 pm Dalton Lecture, Sala Maffei Post-concert Café Viola, Locanda il Bissone 3:00 pm AIV General Meeting, Sala Mercanti 5:10 pm Tabea Zimmermann Master Class, Sala Maffei Friday October 7 6:10 pm Alfonso Ghedin Discuss Viola Set-Up, Sala Maffei 9:00 am ESMAE, Sala Maffei 8:30 pm Opening Concert, Auditorium 9:00 am Shore Workshop, Auditorium Post-concert Café Viola, Locanda il Bissone 10:00 am Giallombardo, Kipelainen Recital, Auditorium Wednesday October 5 11:10 am Palmizio Recital, Sala Maffei 12:10 pm Eckert Recital, Sala Maffei 9:00 am Kosmala Workshop, Sala Maffei 9:00 am Cuneo Workshop, Auditorium 12:10 pm Rotterdam/The Hague Recital, Auditorium 10:00 am Alvarez, Richman, Gerling Recital, Sala Maffei 1:00 pm Street Concerts, Various Locations 11:10 am Tabea Zimmermann Recital, Museo del Violino 2:00 pm Viola Orchestra -

Key of B Flat Minor, German Designation)

B dur C B Dur C BAY DOOR C (key of B flat major, German designation) B moll C b moll C BAY MAWL C (key of b flat minor, German designation) Baaren C Kees van Baaren C KAYAYSS funn BAHAH-renn Babadzhanian C Ar0no Babadzhanian C AR-no bah-buh-jah-nihAHN Babayev C Andrei Babayev C ahn-DRAYEE bah-BAH-yeff Babbi C Cristoforo Babbi C kree-STOH-fo-ro BAHB-bee C (known also as Pietro Giovanni Cristoforo Bartolomeo Gasparre Babbi [peeAY-tro jo-VAHN-nee kree-STOH-fo-ro bar-toh-lo- MAY-o gah-SPAHR-ray BAHB-bee]) Babbi C Gregorio Babbi C gray-GAW-reeo BAHB-bee Babbi C Gregorio Babbi C gray-GAW-reeo BAHB-bee C (known also as Gregorio Lorenzo [lo-RAYN-tso] Babbi) Babic C Konstantin Babi C kawn-stahn-TEEN BAH-bihch Babin C Victor Babin C {VICK-tur BA-b’n} VEEK-tur BAH-binn Babini C Matteo Babini C maht-TAY-o bah-BEE-nee Babitz C Sol Babitz C SAHL BA-bittz Bacarisse C Salvador Bacarisse C sahl-vah-THAWR bah-kah-REESS-say Baccaloni C Salvatore Baccaloni C sahl-vah-TOH-ray bahk-kah-LO-nee Baccanale largo al quadrupede C Baccanale: Largo al quadrupede C bahk-kah-NAH-lay: LAR-go ahl kooah-droo-PAY-day C (choral excerpt from the opera La traviata [lah trah- veeAH-tah] — The Worldly Woman; music by Giuseppe Verdi [joo-ZAYP-pay VAYR-dee]; libretto by Francesco Maria Piave [frahn-CHAY-sko mah-REE-ah peeAH-vay] after Alexandre Dumas [ah-leck-sah6-dr’ dü-mah]) Bacchelli C Giovanni Bacchelli C jo-VAHN-nee bahk-KAYL-lee Bacchius C {BAHK-kihôôss} VAHK-kawss Baccholian singers of london C Baccholian Singers of London C bahk-KO-lee-unn (Singers of London) Bacchus C -

Tokenism in the Representation of Women Composers on BBC Radio 3

The Other Composer: Tokenism in the Representation of Women Composers on BBC Radio 3 Valerie Abma (5690323) Deadline: 15 juni, 2018 Begeleider: dr. Ruxandra Marinescu BA Eindwerkstuk Muziekwetenschap Universiteit Utrecht MU3V14004 2017-2018 Blok 4 Table of Contents Abstract.…………………………………….………………………………………………… 3 Introduction: The Other Composer.…………………...……………………………………… 4 Chapter 1: The Negligible Impact.……………………………….…………………………… 7 Chapter 2: BBC Radio 3 and its aims.………………………………………………………. 11 Chapter 3: BBC Radio 3 and its tokenism………………………………….…..…………….14 3.1: The BBC guidelines for diversity……………………………….……………….14 3.2: Programming…………………………………………………………………… 15 3.3: “Mind your language”.…………………….…………………………………… 17 Conclusion.…………………………………………………..……………………………… 20 Bibliography.…………………………………………………...…………………………… 22 BBC Website Data.……………………..…………………………………………… 25 Appendix 1.…………………………………………………………………………..……… 27 Appendix 2.…………………………………………..……………………………………… 31 Appendix 3.…………………………………………..……………………………………… 39 Appendix 4.…………………………………………...………………………………………44 2 Abstract This thesis focuses on the tokenism, which, as I will demonstrate, is present in the representation of women composers on BBC Radio 3. More specifically, this thesis looks at how tokenism hinders the equality in the representation of men and women composers. The presence of tokenism will be illustrated by data of BBC Radio 3 from 2015 until 2018. As long as compositions by women composers are programmed as tokens, and therefore only as a gesture of temporary change within a dedicated space -

Journal of the American Viola Society Volume 32 No. 1, Spring 2016

Features: Bartolomeo Campagnoli and His 41 Capricci An Afternoon at Skittles: On Playing Mozart’s “Kegelstatt” Trio Part I Volume 32 Number 1 Number 32 Volume Journal of the American ViolaSociety American the of Journal Viola V32 N1.indd 301 3/16/16 6:20 PM Viola V32 N1.indd 302 3/16/16 6:20 PM Journal of the American Viola Society A publication of the American Viola Society Spring 2016: Volume 32, Number 1 p. 3 From the Editor p. 5 From the President News & Notes p. 7 Announcements Feature Articles p. 9 Bartolomeo Campagnoli and His 41 Capricci: The Ever-Changing Role of the Virtuosic Viola and Its Technique: Dalton Competition prize-winner Alicia Marie Valoti explores a history of the Campagnoli 41 Capricci and its impact on the progression of the viola’s reputation as a virtuosic instrument. p. 19 An Afternoon at Skittles: On Playing Mozart’s “Kegelstatt” Trio Part I: A Trio for Signora Dinimininimi, Nàtschibinìtschibi, and Pùnkitititi: Edward Klorman gives readers an interesting look into background on the Mozart “Kegelstatt” Trio. Departments p. 29 New Music: Michael Hall presents a number of exciting new works for viola. p. 35 Outreach: Janet Anthony and Carolyn Desroisers give an account of the positive impact that BLUME is having on music education in Haiti. p. 39 Retrospective: JAVS Associate Editor David M. Bynog writes about the earliest established viola ensemble in the United States. p. 45 Student Life: Zhangyi Chen describes how one of his choral compositions became the basis of a new viola concerto. p. -

TOCC0514DIGIBKLT.Pdf

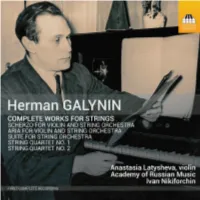

HERMAN GALYNIN – A CANDLE BURNING AT BOTH ENDS by Yuri Abdokov The history of Herman Galynin – a musician considered a natural genius by his teachers Dmitry Shostakovich and Nikolai Myaskovsky – could provide the basis of a tumultuous novel, and this despite the fact that he lived for only 44 years, with the larger, and the more important, part of his output composed during the short time he spent as a student. Herman Hermanovich Galynin1 was born on 30 March 1922 in the ancient city of Tula, located in the north of the Central Russian Upland near the Upa river, 200 kilometres south of Moscow. Tula has long been famous for three diverse crafts that have become historical symbols of the city: weapons, samovars and gingerbread production.2 The future composer came from a family of skilled workers at the Tula arms factory. He lost his parents at the age of seven3 and, like hundreds of thousands of children after the Civil War in post-revolutionary Russia, became homeless. For two years, the boy wandered with a group of ragged and impoverished children of more or less the same age, earning his bread in street brawls, which often ended in the death of street children or their disappearance without trace. Herman was the fourth child in his family; the fate of his siblings is unknown. It is possible that the trials that befell him during this period of starved vagrancy fatally affected his life many years later. In the mid-1930s, thousands of orphanages were opened across the country, thanks to which many orphans were not only physically safeguarded but also raised 1 In some positions the Russian letter Г (ge) is conventionally transcribed into the Roman alphabet with an H. -

Toccata Classics TOCC 0112 Notes

VISSARION SHEBALIN AND HIS A CAPELLA CHORAL CYCLES by Yuri Abdokov Vissarion Shebalin was born on 11 June 1902 in Omsk, a city in the southern part of the western Siberian plateau. His father, Yakov Vasilievich Shebalin, a mathematics teacher, was very fond of music; he had a good voice and an excellent knowledge of choral repertoire, and even directed an amateur gymnasium (secondary-school) choir. he composer’s mother, Apollinaria Apollonovna, was also brought up in a family where music was prominent: her father played the violin. Both parents oten made music at home, and every Saturday musical evenings were organised and mainly vocal music rehearsed and performed. As Shebalin later remembered, My irst musical impressions are connected to my family. I remember vaguely – it must have been in my very early childhood – a large gathering, where everyone was singing, and my father energetically waved his hands. Later I found out that it was one of the choral rehearsals.1 Shebalin began to study piano at the age of eight, and from ten he was a student in the piano class of the Omsk Division of the Russian Musical Society.2 In 1919 he inished middle school and spent the next eighteen months studying in the Agricultural Institute (the only university in Omsk at the time), until a Music College opened, to which Shebalin transferred immediately. While still a student, he was active as a conductor of the Omsk Academic Choir, and in 1921 he began to study theory and composition with Mikhail Nevitov, who soon wrote to Reinhold Gliere and Nikolai Myaskovsky, asking them to hear his student’s compositions.