Trees on Hedges in Cornwall

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Improvedforestharvesting and Reduced Impact Logging in Asia Pacific Region

STATE OF 111E ARI REl^ORI ON IMPROVEDFORESTHARVESTING AND REDUCED IMPACT LOGGING IN ASIA PACIFIC REGION PRE-PROJECT PPD 19/99 REV. itF) STRENGTHENING SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENTOF NATURAL FOREST IN ASIA-PASIFIC , Cover page: Skidding 45, Reduced Impact Logging Activities, " Berau Forest Management Project (BMFP) " Location: Petak 29, Swakelola Labanan, East Kalimantan, PT. In hutani I STATE OF 11/1E ARI REPORT ON IMPROVEDFORESTHARVESTING AND REDUCED IMPACT LOGGING IN ASIA PACIFIC REGION PRE-PROJECT PPD 19199 REV. I (F) STRENGTHENINGSUSTAINABLEMANAGEMENTOF (^)^ NATURAL FOREST IN ASIA-PASIFIC o ITTO I FOREWORD The Indonesia Ministry of Forestry, in its capacity as Task Manager for the Asia-Pacific Forestry Commission's Ad Hoc Working Group on Sustainable Forest Management, with support from the International Tropical Timber Organization has implemented a pre-project focused on the application of the code of practice for forest harvesting in Asia- Pacific. The development objective of the pre-project PPD I 9199 Rev. , (F); "Strengthening Sustainable Management of Natural Forest in Asia-Pacific" is to promote the contribution of forest harvesting to sustainable management of tropical forest in Asia-Pacific countries. It is expected that after the pre-project completion the awareness of improves forest harvesting practices will have been significantly raised and political support for the implementation of the Code secured. To implement a comprehensive training programme and to operationalize demonstration sites for RIL implementation there is a need to understand the status of forest management particularly state of the art on forest harvesting in each Asia Pacific country. This state of the art report was prepared by Dr. -

Tree Preservation Orders: a Guide to the Law and Good Practice

Tree Preservation Orders: A Guide to the Law and Good Practice On 5th May 2006 the responsibilities of the Office of the Deputy Prime Minister (ODPM) transferred to the Department for Communities and Local Government. Department for Communities and Local Government Eland House Bressenden Place London SW1E 5DU Telephone: 020 7944 4400 Website: www.communities.gov.uk Documents downloaded from the www.communities.gov.uk website are Crown Copyright unless otherwise stated, in which case copyright is assigned to Queens Printer and Controller of Her Majestys Stationery Office. Copyright in the typographical arrangement rests with the Crown. This publication, excluding logos, may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium for research, private study or for internal circulation within an organisation. This is subject to it being reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Crown copyright and the title of the publication specified. Any other use of the contents of this publication would require a copyright licence. Please apply for a Click-Use Licence for core material at www.opsi.gov.uk/click-use/system/online/pLogin.asp or by writing to the Office of Public Sector Information, Information Policy Team, St Clements House, 2-16 Colegate, Norwich NR3 1BQ. Fax: 01603 723000 or e-mail: [email protected]. This publication is only available online via the Communities and Local Government website: www.communities.gov.uk Alternative formats under Disability Discrimination -

Download a Prospectus

CAREERS & COURSES GUIDE 2021 FOR SCHOOL LEAVERS Welcome to #thecareercollege WELCOME CHOOSE Welcome to The Cornwall College Group and thank you for considering the incredible opportunities that Over 1,200 acres for Award-winning await you at one of our fantastic campuses. I’m sure as you explore the prospectus, like most people, you THE CAREER COLLEGE will quickly realise why we are also known as ‘The Career College’. land-based training students and staff This careers and courses guide has been designed for school leavers and focuses on career Our mission is to provide exceptional education and training for every learner to improve their career pathways. Our course information provides details of full-time study options (career edge) prospects. We know that your future success needs more than just a certificate. It requires a meaningful and engaging course that has been developed alongside employers. Our courses ensure you have all the skills or apprenticeships (career now). It showcases a wide choice of careers, available through and experience required for you to secure that rewarding career or progress onto higher qualifications. our broad-based curriculum, from agriculture to zoology and everything in between. The great news is there has never been a better time to study with us. We have invested heavily in our £30 million investment in Industry partners to ensure campuses, our teaching and our student experiences. A passion for learning, training and rewarding careers equipment and connectivity courses stay relevant can be felt on every campus in our Group. Our incredible story is receiving positive local and national attention and we would love for you to be part of this. -

BRSUG Number Mineral Name Hey Index Group Hey No

BRSUG Number Mineral name Hey Index Group Hey No. Chem. Country Locality Elements and Alloys (including the arsenides, antimonides and bismuthides of Cu, Ag and B-37 Copper Au) 1.1 4[Cu] U.K., 17 Basset Mines, nr. Redruth, Cornwall Elements and Alloys (including the arsenides, antimonides and bismuthides of Cu, Ag and B-151 Copper Au) 1.1 4[Cu] U.K., 17 Phoenix mine, Cheese Wring, Cornwall Elements and Alloys (including the arsenides, antimonides and bismuthides of Cu, Ag and B-280 Copper Au) 1.1 4[Cu] U.K., 17 County Bridge Quarry, Cornwall Elements and Alloys (including the arsenides, antimonides and bismuthides of Cu, Ag and South Caradon Mine, 4 miles N of Liskeard, B-319 Copper Au) 1.1 4[Cu] U.K., 17 Cornwall Elements and Alloys (including the arsenides, antimonides and bismuthides of Cu, Ag and B-394 Copper Au) 1.1 4[Cu] U.K., 17 ? Cornwall? Elements and Alloys (including the arsenides, antimonides and bismuthides of Cu, Ag and B-395 Copper Au) 1.1 4[Cu] U.K., 17 Cornwall Elements and Alloys (including the arsenides, antimonides and bismuthides of Cu, Ag and B-539 Copper Au) 1.1 4[Cu] North America, U.S.A Houghton, Michigan Elements and Alloys (including the arsenides, antimonides and bismuthides of Cu, Ag and B-540 Copper Au) 1.1 4[Cu] North America, U.S.A Keweenaw Peninsula, Michigan, Elements and Alloys (including the arsenides, antimonides and bismuthides of Cu, Ag and B-541 Copper Au) 1.1 4[Cu] North America, U.S.A Keweenaw Peninsula, Michigan, Elements and Alloys (including the arsenides, antimonides and bismuthides of Cu, -

The Cornwall College Group Higher Education Student Handbook 2020

The Cornwall College Group Higher Education Student Handbook 2020-2021 1 | P a g e Dear HE Student, As we set out on the 2020-21 academic year I would like to welcome HE Students both new and returning to study. We have never been prouder of our HE provision at Cornwall College and you, as both undergraduate and postgraduate students, are at the heart of what makes it so special. Each one of you is on an individual journey of discovery and education attainment and we hope to learn more about each of your stories as the year goes on. We recognise that the start of this academic year has been particularly different. The fact that you are enrolled on your degree and have commenced study, or returned after successfully completing your stage of study last year, is an achievement in itself. This student handbook contains information that will help you throughout your year to achieve and find the support when and where you need it. Over the summer, our Programme Teams have worked to timetable your study in a way that makes your study time in college both productive and safe. The College continues to work closely with Public Health England in order to continue this. Should we, either as class or campus find ourselves in a position that we are required to deliver online as a result of Covid-19, timetabled sessions will immediately commence online via Microsoft Teams. As well as supporting ‘lecture’ delivery, the functionality of teams means that you will also be able to continue receiving the peer-to-peer support and dialogue of your cohort. -

1850 Cornwall Quarter Sessions and Assizes

1850 Cornwall Quarter Sessions and Assizes Table of Contents 1. Epiphany Sessions ..................................................................................................................................... 1 2. Lent Assizes ............................................................................................................................................... 8 3. Easter Sessions ........................................................................................................................................ 46 4. Midsummer Sessions .............................................................................................................................. 54 5. Summer Assizes ....................................................................................................................................... 69 6. Michaelmas Sessions ............................................................................................................................... 93 Royal Cornwall Gazette 4 and 11 January 1850 1. Epiphany Sessions These Sessions were opened on Tuesday, the 1st of January, before the following magistrates:— J. KING LETHBRIDGE, Esq. Chairman; Sir W. L. S. Trelawny, Bart. E. Stephens, Esq. T. J. Agar Robartes, Esq., M.P. R. Gully Bennet, Esq. N. Kendall, Esq. T. H. J. Peter, Esq. W. Hext, Esq. H. Thomson, Esq. J. S. Enys, Esq. D. P. Hoblyn, Esq. J. Davies Gilbert, Esq. Revds. W. Molesworth, C. Prideaux Brune, Esq. R. G. Grylls, C. B. Graves Sawle, Esq. A. Tatham, W. Moorshead, Esq. T. Phillpotts, W. -

Camborne School of Mines CSMM143: Poldice Assignment James Heslington: 640012228

College of Engineering, Mathematics & Physical Sciences Camborne School of Mines CSMM143: Poldice Assignment James Heslington: 640012228 CSMM143: GIS for Surveyors Poldice Assignment 640012228 Contents Part A ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 1.1. Overview ........................................................................................................................................ 3 2.1. Site 1 Data ....................................................................................................................................... 4 2.2. Interpretation ................................................................................................................................................ 6 2.3. Spatial Recommendations ............................................................................................................................. 6 2.4. Recommendations ......................................................................................................................................... 6 3.1. Site 2 Data ...................................................................................................................................... 7 Part B .................................................................................................................................................... 11 Aim ..................................................................................................................................................... -

The Isabella Plantation Conservation Management Plan February 2012

The Isabella Plantation Conservation Management Plan February 2012 Isabella Plantation Landscape Conservation Management Plan 2012 Prepared by The Royal Parks January 2012 The Royal Parks Rangers Lodge Hyde Park London W2 2UH Tel: 020 7298 2000 Fax: 020 7402 3298 [email protected] i Isabella Plantation Conservation Management Plan CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................. 3 Richmond Park ............................................................................................................................................. 3 The Management Plan ................................................................................................................................ 4 Aims of the Isabella Plantation Management Plan ................................................................................ 4 Structure of the Plan .................................................................................................................................. 6 2.0 GENERAL AND MANAGEMENT CONTEXT ............................... 7 Location ......................................................................................................................................................... 7 Existing TRP Management Framework ................................................................................................ 10 Management Structure of Richmond Park .......................................................................................... 10 Landscape Management -

Sheffield Trees and Woodlands Strategy 2016-2030

Sheffield Trees and Woodlands Strategy 2016-2030 Sheffield City Council September 2016 Consultation Draft Key Strategic Partners Forest Schools Forestry Commission Froglife National Trust Natural England Peak District National Park Authority Sheffield and Rotherham Wildlife Trust Sheffield Green Spaces Forum Sheffield Hallam University Sheffield Local Access Forum Sheffield University Sorby Natural History Society South Yorkshire Forest Partnership Sport England Woodlands Trust Contents Foreword ................................................................................................................................................. 1 1. Context ............................................................................................................................................ 2 1.1 Background ............................................................................................................................. 2 1.2 What the Strategy Covers ....................................................................................................... 2 1.3 Legislation, Policy and Strategy Linkages ................................................................................ 3 1.4 Our Vision and Aims ................................................................................................................ 3 1.5 Strategy Monitoring and Review ............................................................................................ 4 1.6 Additional Documents ........................................................................................................... -

The Newsletter for Broadland Tree Wardens

Broadsheet The Magazine for Broadland Tree Wardens Issue 181 – October 2019 A Busy0 Month Broadsheet A Busy Month The Monthly Magazine for Broadland Tree Wardens ITHOUT doubt, October is going to be a busy month Issue 181 – October 2019 for Broadland Tree Wardens. We have what are possibly the two most important dates in our calendar W Inside this issue with the East Anglian Regional Tree Wardens’ Forum on Sunday 6 October in Reedham Village Hall, followed by our A Busy Month - Editorial 1 100 Years of the Forestry Commission 4 first AGM on Wednesday 16 October in Freethorpe Village Hall. Great Trees with even Greater Burdens 5 Now, I know I’ve said it before unsustainable economy with a “planet-sized (many times before in fact), and I debt” caused by climate breakdown, the groups Call for a Million People to Plant Trees 6 said. Tree Charter Day 6 will no doubt say it again (just as Although broadly welcoming the 2050 Is the World Really Ablaze? 7 many times I guess) but if you don’t target, promised by Theresa May among the attend any other Network events final acts of her premiership, the charities said Felling of Suffolk Wood to go Ahead 8 during the year these are the two the date needed to be brought forward by Giant Trees Susceptible to 3 Killers 9 several years and that policy and funding you must make every effort to Climate Change and Forestry 10 arrangements were not yet in place. attend. In the letter, the organisations urged the 800 Years Tracked by Tree Rings 10 Details of both events have been circulated chancellor to demonstrate that he understood Veteran Tree Management Certification11 together with the Agenda for our AGM and I the gravity of the challenge by holding a climate How Forests Shaped Literary Heritage 12 urge you to encourage members of your and nature emergency budget to unleash a town/parish council to also attend. -

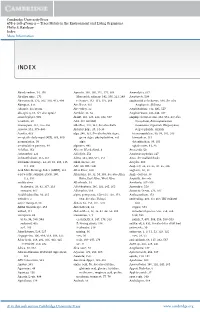

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-47093-3 — Trace Metals in the Environment and Living Organisms Philip S

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-47093-3 — Trace Metals in the Environment and Living Organisms Philip S. Rainbow Index More Information INDEX Aberdeenshire, 34, 156 Agrostis, 148, 160, 251, 271, 664 Ammodytes, 627 Aberllyn mine, 173 Merseyside refinery, 142, 166, 221, 249 Ampharete, 598 Aberystwyth, 172, 307, 370, 471, 498 tolerance, 172–173, 175, 268 ampharetid polychaetes, 598, See also Abington, 312 Aire River, 432 Ampharete, Melinna Abramis. See bream Aire valley, 32 Amphibalanus, 112, 495, 557 absorption, 68, See also uptake Airedale, 33, 54 Amphinemura, 343–344, 387 Acanthephyra, 585 ALAD, 116, 124, 222, 382, 547 amphipod crustaceans, 362, 551, See also acanthite, 29 Alca. See razorbill Corophium, Echinogammarus, Acarospora, 152, 155–156 alderflies, 318, 361, See also Sialis Gammarus, hyperiids, Rhepoxynius, Acartia, 551, 579–580 Alderley Edge, 27, 34–36 stegocephalids, talitrids Acaster, 432 alga, 286, 323, See also brown algae, bioaccumulation, 90, 99, 101, 103 acceptable daily input (ADI), 266, 660 green algae, phytoplankton, red biomarkers, 119 accumulation, 90 algae detoxification, 98, 101 accumulation patterns, 99 alginates, 441 uptake rates, 83, 85 Achillea, 163 Alice in Wonderland, 8 Anaconda, 50 Achnanthes, 321 Aliivibrio, 551 Analasmocephalus, 247 Achnanthidium, 321–322 Alitta, 443, 450, 515, 551 Anas. See mallard ducks acid mine drainage, 22, 29, 66, 288, 315, alkali disease, 20 Ancylus, 366 317, 389 Alle. See little auk Anglesey, 26, 33, 35, 47, 55, 306 Acid Mine Drainage Index (AMDI), 316 Allen River, 160 anglesite, 28, 33 acid volatile sulphide (AVS), 286, Allendales, 28, 32, 54, 309, See also Allen Anglo-Saxons, 36 315, 397 River, East Allen, West Allen Anguilla. -

Coast-To-Coast Walkers Trail.Pub

Mining Trails – The Coast-to-Coast Walkers Trail – Portreath to Devoran and Penpol – 16.74 miles ********************************************************************************************** Full Route Directions, with the emphasis on detours for walkers only, avoiding the cycle route ************************************************************************************** Portreath to Cambrose, on the official cycle trail – 2.10 miles Start at the furthest NE corner of Portreath Harbour at 65489/45483. Start on the Coast-to-Coast, passing storyboards ( Portreath Harbour, Tramroad and Incline ) and follow a granite marker ( Devoran 12 miles ) bearing L on a track and a road (Lighthouse Hill and Cliff Terrace) to the Portreath Arms Hotel ( B&B ) on your L. At 0.19 miles follow MT sign (Devoran 11 ) on Sunnyvale Road At 0.47 miles, the road continues as a tarmac lane through trees. At an MT post at 0.51 miles, the lane becomes a rough track, through a gap by a gate ( sign Cornish Way ). After 20 yards pass a granite plaque ( Duke of Leeds Hills ), the route continues as a track through woodland, with the Redruth road below on the R. At 0.60 miles the track becomes tarmac, continuing through woods. At 1.05 miles go through a gap by a gate, cross a road, and through another gap by a gate ( marker Tolticken Hill ). The track continues as tarmac, through a hunting gate at Bridge ( Bridge Inn below ). ( 1.27 miles ) The tarmac ends and a track continues, through a gate, still in woodland, ( marker Bridge at 1.30 miles ) At a fork at 1.34 miles go R (WM), now between high hedges . At 1.77 miles, looking R you get your first view to Carn Brea .