Improvedforestharvesting and Reduced Impact Logging in Asia Pacific Region

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tree Preservation Orders: a Guide to the Law and Good Practice

Tree Preservation Orders: A Guide to the Law and Good Practice On 5th May 2006 the responsibilities of the Office of the Deputy Prime Minister (ODPM) transferred to the Department for Communities and Local Government. Department for Communities and Local Government Eland House Bressenden Place London SW1E 5DU Telephone: 020 7944 4400 Website: www.communities.gov.uk Documents downloaded from the www.communities.gov.uk website are Crown Copyright unless otherwise stated, in which case copyright is assigned to Queens Printer and Controller of Her Majestys Stationery Office. Copyright in the typographical arrangement rests with the Crown. This publication, excluding logos, may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium for research, private study or for internal circulation within an organisation. This is subject to it being reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Crown copyright and the title of the publication specified. Any other use of the contents of this publication would require a copyright licence. Please apply for a Click-Use Licence for core material at www.opsi.gov.uk/click-use/system/online/pLogin.asp or by writing to the Office of Public Sector Information, Information Policy Team, St Clements House, 2-16 Colegate, Norwich NR3 1BQ. Fax: 01603 723000 or e-mail: [email protected]. This publication is only available online via the Communities and Local Government website: www.communities.gov.uk Alternative formats under Disability Discrimination -

Forest Grazing and Natural Regeneration in a Late Successional Broadleaved Community Forest in Bhutan

Mountain Research and Development (MRD) MountainResearch An international, peer-reviewed open access journal Systems knowledge published by the International Mountain Society (IMS) View metadata, citation andwww.mrd-journal.org similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Mountain Forum Forest Grazing and Natural Regeneration in a Late Successional Broadleaved Community Forest in Bhutan Bill Buffum1*, Georg Gratzer1, and Yeshi Tenzin2 * Corresponding author: [email protected] 1 Institute of Forest Ecology, University of Natural Resources and Applied Life Sciences, Peter Jordan-Straße 82, A-1190 Wien, Austria 2 Mongar Range Office, Department of Forests, Mongar District, Bhutan This study investigated decreased and the number of naturally regenerated tree the sustainability of seedlings and saplings significantly increased. There were no combining forest grazing other changes in forest management practices during the and timber harvesting period that would affect natural regeneration, and there were with selection felling in no significant changes in the volume of wood harvested or a cool broadleaved the volume/number of standing trees (with a diameter at community forest (CF) in breast height $10 cm). We concluded that moderate Bhutan. Forest grazing intensities of forest grazing (0.4 cattle*ha21) and timber and timber production harvesting (4.64 m3*ha21*y21) can be combined in this are critical livelihood type of forest without negative impacts on forest activities for many farmers throughout the world, so it is regeneration. Our findings support Bhutan’s policy of important to understand under what conditions the 2 allowing forest grazing in CFs. activities can be combined. The study was based on a household survey to quantify livestock holdings and grazing Keywords: Community forestry; forest regeneration; patterns, a comparison of 2 forest inventories to assess selection felling; forest policy; cattle grazing; Bhutan. -

Fuelwood Use and Availability in Bhutan: Implications for National Policy and Local Forest Management

Hum Ecol (2014) 42:127–135 DOI 10.1007/s10745-013-9634-4 Fuelwood Use and Availability in Bhutan: Implications for National Policy and Local Forest Management Sangay Wangchuk & Stephen Siebert & Jill Belsky Published online: 6 December 2013 # Springer Science+Business Media New York 2013 Abstract Fuelwood is the principal energy resource for mil energy source for over 2 billion, primarily poor people (FAO lions of households around the world, yet its use, availability 1997;Pattanayaket al. 2004) and fuelwood harvesting ac and management remain poorly understood in many areas. We counts for over 54 % of total annual wood removal from document fuelwood consumption, growth/yield and standing forests (Bhatt and Sachan 2003). Approximately 1.7 billion biomass in a Bhutanese village and alpine area used season m3 of fuelwood and charcoal were produced globally in 2004 ally by villagers where the government is concerned about (IEA 2006) and wood-based fuels comprise about 80 % of harvesting in a recently designated national park. Pinus total household energy consumption (Sharma and Banskota wallichiana was the only fuelwood used in the village and 2005) and 35 % of total energy use in developing countries assessments suggest 52 ha could sustain local needs at current (Dovie et al. 2004). Low income countries account for about consumption levels (54 m3/household/yr). In contrast, Rho 90 % of global fuelwood consumption (Broadhead et al. dodendron aeruginosum was used in the alpine site and at 2001) and the number of people who depend on fuelwood is current consumption rates all will be consumed by 2023. Our increasing with at least 1.7 billion expected to do so in Asia findings emphasize the need to manage fuelwood based on alone by 2030 (Arnold and Persson 2003;IEA2006 ). -

The Isabella Plantation Conservation Management Plan February 2012

The Isabella Plantation Conservation Management Plan February 2012 Isabella Plantation Landscape Conservation Management Plan 2012 Prepared by The Royal Parks January 2012 The Royal Parks Rangers Lodge Hyde Park London W2 2UH Tel: 020 7298 2000 Fax: 020 7402 3298 [email protected] i Isabella Plantation Conservation Management Plan CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................. 3 Richmond Park ............................................................................................................................................. 3 The Management Plan ................................................................................................................................ 4 Aims of the Isabella Plantation Management Plan ................................................................................ 4 Structure of the Plan .................................................................................................................................. 6 2.0 GENERAL AND MANAGEMENT CONTEXT ............................... 7 Location ......................................................................................................................................................... 7 Existing TRP Management Framework ................................................................................................ 10 Management Structure of Richmond Park .......................................................................................... 10 Landscape Management -

Sheffield Trees and Woodlands Strategy 2016-2030

Sheffield Trees and Woodlands Strategy 2016-2030 Sheffield City Council September 2016 Consultation Draft Key Strategic Partners Forest Schools Forestry Commission Froglife National Trust Natural England Peak District National Park Authority Sheffield and Rotherham Wildlife Trust Sheffield Green Spaces Forum Sheffield Hallam University Sheffield Local Access Forum Sheffield University Sorby Natural History Society South Yorkshire Forest Partnership Sport England Woodlands Trust Contents Foreword ................................................................................................................................................. 1 1. Context ............................................................................................................................................ 2 1.1 Background ............................................................................................................................. 2 1.2 What the Strategy Covers ....................................................................................................... 2 1.3 Legislation, Policy and Strategy Linkages ................................................................................ 3 1.4 Our Vision and Aims ................................................................................................................ 3 1.5 Strategy Monitoring and Review ............................................................................................ 4 1.6 Additional Documents ........................................................................................................... -

2014Iufrocongress Accepted Abstracts by Theme Session Country.Xlsx 1 of 162

2014IUFROCongress_Accepted Abstracts by Theme_Session_Country.xlsx 1 of 162 First Name of Last Name of Congress Theme Session Title Country of Residence Affiliation/Organization Presentation Title Presenting Author Presenting Author Advances in large-scale forest inventories to support Universidade Regional de Contribution of Floristic and Forest Inventory of Santa Catarina (IFFSC) to Sub-plenary session the monitoring and the assessment of forest Alexander Vibrans Brazil Blumenau large scale forest biodiversity assessment biodiversity and ecosystem services Assessing information for indicators on SFM: potentials and pitfallsCriteria Advances in large-scale forest inventories to support and indicators (C&I) have emerged as a powerful tool to promote Sub-plenary session the monitoring and the assessment of forest Michael Koehl Germany University of Hamburg sustainable forest management (SFM). Several international programs and biodiversity and ecosystem services initiatives have developed sets of criteri Advances in large-scale forest inventories to support Sub-plenary session the monitoring and the assessment of forest Lorenzo Fattorini Italy University of Siena Inference on diversity indexes from large-scale forest inventories biodiversity and ecosystem services Advances in large-scale forest inventories to support Development of innovative models for multiscale monitoring of ecosystem Sub-plenary session the monitoring and the assessment of forest Marco Marchetti Italy Italian Academy of Forest Sciences services indicators in Mediterranean -

The Newsletter for Broadland Tree Wardens

Broadsheet The Magazine for Broadland Tree Wardens Issue 181 – October 2019 A Busy0 Month Broadsheet A Busy Month The Monthly Magazine for Broadland Tree Wardens ITHOUT doubt, October is going to be a busy month Issue 181 – October 2019 for Broadland Tree Wardens. We have what are possibly the two most important dates in our calendar W Inside this issue with the East Anglian Regional Tree Wardens’ Forum on Sunday 6 October in Reedham Village Hall, followed by our A Busy Month - Editorial 1 100 Years of the Forestry Commission 4 first AGM on Wednesday 16 October in Freethorpe Village Hall. Great Trees with even Greater Burdens 5 Now, I know I’ve said it before unsustainable economy with a “planet-sized (many times before in fact), and I debt” caused by climate breakdown, the groups Call for a Million People to Plant Trees 6 said. Tree Charter Day 6 will no doubt say it again (just as Although broadly welcoming the 2050 Is the World Really Ablaze? 7 many times I guess) but if you don’t target, promised by Theresa May among the attend any other Network events final acts of her premiership, the charities said Felling of Suffolk Wood to go Ahead 8 during the year these are the two the date needed to be brought forward by Giant Trees Susceptible to 3 Killers 9 several years and that policy and funding you must make every effort to Climate Change and Forestry 10 arrangements were not yet in place. attend. In the letter, the organisations urged the 800 Years Tracked by Tree Rings 10 Details of both events have been circulated chancellor to demonstrate that he understood Veteran Tree Management Certification11 together with the Agenda for our AGM and I the gravity of the challenge by holding a climate How Forests Shaped Literary Heritage 12 urge you to encourage members of your and nature emergency budget to unleash a town/parish council to also attend. -

PP 1 06 Final.Qxp

workshop proceedings Inaugural session The workshop was inaugurated by the Chief Guest, His Excellency, Mr. Badri Prasad Mandal, Minister, Ministry of Forest and Soil Conservation, His Majesty's Government of Nepal. Dr. James Gabriel Campbell, Director General, ICIMOD, welcomed the chief guest and other invitees to the opening session and expressed his special appreciation to the participants from both Nepal and abroad for making the effort to attend the workshop in spite of the long distances involved in some cases. He said that the level of representation from His Majesty’s Government at the opening session, in the presence of none other than the Minister for Forest and Soil Conservation, is a testimony to the importance attached to community forestry in Nepal. Being closely associated with the evolution of community forestry in Nepal, he expressed his satisfaction with the tremendous positive impacts that the scheme had brought about in the livelihoods of the people in the hills of Nepal and to their environment. He expressed his wish that some of the lessons learned during the course of implementing the various community forestry projects supported by many long-time supporters, such as SDC, GTZ, the World Bank, DANIDA [Danish International Development Agency], and DFID [UK Department for International Development], could be shared with participants from other countries. Likewise, there were a number of areas in which participants from Nepal could benefit from the experiences of other countries: viz., managing rangelands, wetlands, and protected areas. Mr. Paul Egger, Head of the East Asia Division, SDC, welcomed the guests and participants on behalf of SDC, and then gave a presentation on the interactions between forest policy and land use patterns using Nepal as an example (full text of the presentation provided in Volume II). -

Community Forestry in Bhutan Contributes to Poverty Reduction While Maintaining the Sustainability of the Resources

Proceedings: International Conference on Poverty Reduction and Forests, Bangkok, September, 2007 Community Forestry in Bhutan Contributes to Poverty Reduction While Maintaining the Sustainability of the Resources K.J. Temphel1 and Hans J.J. Beukeboom2 Community Forestry (CF) in Bhutan started to take off in 2000. As of June 2007, 46 community forests had been approved covering about 4,200 hectares with 2,192 households involved. With the potential to reach 69% of the population (about 95,000 rural households) it has great potential for livelihood improvement. By law the rural population already has access to construction timber and fuelwood against subsidized rates (so-called rural timber supply), but with CF the communities are allowed to sell excess products (both wood and nonwood) as the Forest and Nature Conservation Rules, 2006 created an enabling environment to sell excess products. CF also makes timber for own consumption more easily available as no permits are required after the management plans have been approved. The sale of excess nonwood forest products (NWFPs) from CFs started a few years ago and the number of community forests selling NWFPs is increasing. In late 2007, the first excess timber from two CFs was sold. This shows the benefits and also the potential of how CF contributes to poverty reduction as communities receive income from it. Several communities have the management rights over their NWFPs and thus also the right to sell these products to “outsiders,” thus creating income for the community forest members. Several initiatives have started to establish small-scale enterprises to either produce or sell products in an organized way so communities can benefit even more. -

Well-Being, Happiness, and Public Policy

Well-being, Happiness, and Public Policy Sabina Alkire དཔལ་འབྲུག་筲བ་འὴག་ལྟེ་བ། The Centre for Bhutan Studies & GNH Research Well-being, Happiness, and Public Policy By Sabina Alkire Copyright © 2015 The Centre for Bhutan Studies & GNH Research Published by: The Centre for Bhutan Studies & GNH Research Post Box No. 1111 Thimphu, Bhutan Tel: 975-2-321005/321111 Fax: 975-2-321001 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.bhutanstudies.org.bt ISBN 978-99936-14-79-1 There is no joy like the joy of unleashing the human spirit. There is no laughter like the laughter of those who are happy with others. There is no purpose more noble than to build communities for all. This is our glory. — Eunice Kennedy Shriver. Virtue is bold, and goodness never fearful. — William Shakespeare. Let yourself be silently drawn by the stronger pull of what you really love. —Rumi. We in our life are never more than the crescent moon behind the fullness of ourself. … Destiny doesn‘t mean doing this that or the other. It means touching and savouring the fullness of your being and living more and more clearly and continuously from within it — Cynthia Bourgealt. The right to search for truth implies also a duty; One must not conceal any part of what one has recognized to be true. — Albert Einstein. iii Contents ABSTRACT .............................................................................................. vii Well-being, Happiness, and Public Policy ............................................ 1 Our aim: Success, not Utopia ................................................................ 3 Motivation: Well-being and its distinct domains ................................ 6 Well-being has multiple domains ........................................................ 7 What is a dimension (domain) of well-being?................................... -

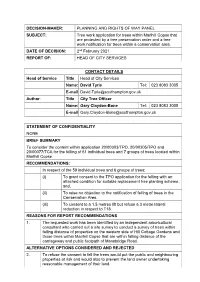

Tree Work Application for Trees Within Marlhill

DECISION-MAKER: PLANNING AND RIGHTS OF WAY PANEL SUBJECT: Tree work application for trees within Marlhill Copse that are protected by a tree preservation order and a tree work notification for trees within a conservation area. DATE OF DECISION: 2nd February 2021 REPORT OF: HEAD OF CITY SERVICES CONTACT DETAILS Head of Service Title Head of City Services Name: David Tyrie Tel: 023 8083 3005 E-mail: [email protected] Author: Title City Tree Officer Name: Gary Claydon-Bone Tel: 023 8083 3005 E-mail: [email protected] STATEMENT OF CONFIDENTIALITY NONE BRIEF SUMMARY To consider the content within application 20/00303/TPO, 20/00305/TPO and 20/00077/TCA for the felling of 61 individual trees and 7 groups of trees located within Marlhill Copse. RECOMMENDATIONS: In respect of the 59 individual trees and 6 groups of trees: (i) To grant consent to the TPO application for the felling with an attached condition for suitable replacement tree planting scheme, and, (ii) To raise no objection to the notification of felling of trees in the Conservation Area. (iii) To consent to a 1.5 metres lift but refuse a 3 metre lateral reduction in respect to T18. REASONS FOR REPORT RECOMMENDATIONS 1. The requested work has been identified by an independent arboricultural consultant who carried out a site survey to conduct a survey of trees within falling distance of properties on the western side of Hill Cottage Gardens and those trees within Marlhill Copse that are within falling distance of the carriageway and public footpath of Mansbridge Road. -

Trees, Woodlands & Development Craobhan, Coilltean Agus Leasachad

Supplementary Guidance Stiùireadh Leasachail Trees, Woodlands & Development Craobhan, Coilltean agus Leasachad January 2013 Supplementary Guidance: Trees, Woodlands and Development 1 Introduction Ro-ràdh 1.1 The Value of Trees and Woodland...................................................................... 3 1.2 Purpose of Supplementary Guidance ................................................................ 3 2 Statutory & Non Statutory Regulations Riaghailtean Reachdail agus Neo-reachdail 2.1 Town and Country Planning (Scotland) Act 1997 ........................................ 4 2.2 Scottish Planning Policy .......................................................................................... 4 2.3 Highland wide Local Development Plan ........................................................... 5 2.4 Highland Forest & Woodland Strategy ............................................................. 7 2.5 Scottish Government’s Policy on the Control of Woodland Removal ... 7 2.6 BS5837:2012 (Trees in Relation to Design, Demolition and Construction) ..................... 9 2.7 Tree Preservation Orders and Conservation Areas ....................................... 9 2.8 Felling Licences ......................................................................................................... 10 2.9 Protected Species ..................................................................................................... 10 3 Development within Woodlands Leasachadh taobh a-staigh Choilltean 3.1 Developments Involving Removal of Woodland