Rethinking Dr. Seuss for NEA's Read Across America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pacific Circle

UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII UMA<W THE PACIFIC CIRCLE OCTOBER 2002___________ BULLETIN NO. 9_____________ISSN 1520-3581 CONTENTS PACIFIC CIRCLE NEW S ................................................................ 2 Members’ N ew s ...............................................................................2 Recent Meetings...............................................................................4 Publications...................................................................................... 5 IUHPS/DHS NEW S .............................................................................6 HSS N E W S ..............................................................................................7 PSA N E W S ..............................................................................................8 PACIFIC WATCH ............................................................................... 8 CONFERENCE AND SOCIETY REPORTS ......................... 10 FUTURE CONFERENCES & CALLS FOR PAPERS .. .11 EXHIBITIONS AND MUSEUMS ............................................... 13 EMPLOYMENT, GRANTS AND PRIZES .............................. 13 RESEARCH, ARCHIVES AND COLLECTIONS: PRINT & ELECTRONIC .............................................................. 15 BOOK AND JOURNAL NEWS ..................................................16 BOOK REVIEWS .............................................................................17 PACIFIC BIBLIOGRAPHY ......................................................... 27 ^ecen* B°°ks ..................................................................................27 -

Leg TWO Points

2017 Iron Butt Rally, Leg 2 Allen, TX to Allen, TX Packing List Leg 2 Bonus Pack – Allen, TX to Allen, TX Claimed Bonuses Form Ask Rallymaster if there are any changes or corrections Before leaving the checkpoint, make sure you can find each bonus location and have a clear understanding of what is required to earn the bonus WARNING: DO NOT LEAVE ON A LEG UNTIL YOU HAVE VERIFIED THAT ALL PAPERWORK IS IN YOUR RALLY PACKAGE FOR THAT LEG. EACH PAGE IS NUMBERED. THIS IS YOUR RESPONSIBILITY. CRITICAL: Please be respectful when placing your flag in photos. Private property and priceless museum pieces must not be used as your flag support. To earn any bonus, you MUST claim it on the Claimed Bonuses form. This includes Rest bonuses and Call-In bonuses. If you lose the Claimed Bonuses form, you will earn no bonus points for the leg. REMEMBER: Unless otherwise specified, I.D. Flags are required in all photos. Page 1 of 12 Scoring Instructions All bonuses are available at point values listed in this pack within the time restrictions listed in the rally book. Bonuses in the rally book are divided into five categories: Air, Land, Mythical, Prehistoric, and Water. Those categories are denoted in the bonus codes by the first letter of the code. For example, the “A” in code “ABB” indicates this as an “Air” bonus. Riders who successfully visit and claim four(4) bonuses in a row from different categories will earn triple (3x) the listed value of the fourth bonus in that string of four. -

Zerohack Zer0pwn Youranonnews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men

Zerohack Zer0Pwn YourAnonNews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men YamaTough Xtreme x-Leader xenu xen0nymous www.oem.com.mx www.nytimes.com/pages/world/asia/index.html www.informador.com.mx www.futuregov.asia www.cronica.com.mx www.asiapacificsecuritymagazine.com Worm Wolfy Withdrawal* WillyFoReal Wikileaks IRC 88.80.16.13/9999 IRC Channel WikiLeaks WiiSpellWhy whitekidney Wells Fargo weed WallRoad w0rmware Vulnerability Vladislav Khorokhorin Visa Inc. Virus Virgin Islands "Viewpointe Archive Services, LLC" Versability Verizon Venezuela Vegas Vatican City USB US Trust US Bankcorp Uruguay Uran0n unusedcrayon United Kingdom UnicormCr3w unfittoprint unelected.org UndisclosedAnon Ukraine UGNazi ua_musti_1905 U.S. Bankcorp TYLER Turkey trosec113 Trojan Horse Trojan Trivette TriCk Tribalzer0 Transnistria transaction Traitor traffic court Tradecraft Trade Secrets "Total System Services, Inc." Topiary Top Secret Tom Stracener TibitXimer Thumb Drive Thomson Reuters TheWikiBoat thepeoplescause the_infecti0n The Unknowns The UnderTaker The Syrian electronic army The Jokerhack Thailand ThaCosmo th3j35t3r testeux1 TEST Telecomix TehWongZ Teddy Bigglesworth TeaMp0isoN TeamHav0k Team Ghost Shell Team Digi7al tdl4 taxes TARP tango down Tampa Tammy Shapiro Taiwan Tabu T0x1c t0wN T.A.R.P. Syrian Electronic Army syndiv Symantec Corporation Switzerland Swingers Club SWIFT Sweden Swan SwaggSec Swagg Security "SunGard Data Systems, Inc." Stuxnet Stringer Streamroller Stole* Sterlok SteelAnne st0rm SQLi Spyware Spying Spydevilz Spy Camera Sposed Spook Spoofing Splendide -

Geisel Library

Geisel Library Gauri Nadkarni, Preston Scott, Kasi Svoboda, Shaghayegh Taheri, Julie Wright, Guang Yang Introduction Typology: University Central Library Architect: William L. Pereira Location: University of California, San Diego (La Jolla, California) Date: 1970 Area: 255,000 sqft Dedicated to Audrey & Theodore Seuss Geisel (Dr. Seuss) in 1995 Background Campus Master Plan The Architect: William L. Pereira Born: April 25, 1909; Chicago, Illinois Education: University of Illinois (1931) Career: Started 3 architectural firms over his life lifetime Movie making business Professor of architecture at University of Southern California Style: Brutalist Functionalist Pre-Cast Concrete Design Concept Program: 3,000 readers 2,500,000 books Design Concept Forum 16 columns Design Concept Forum Design Concept Below Forum Public Floor Main entrance Staff areas Library Services Basement Staff areas Mechanical Design Concept Below Forum Design Concept Above Forum 5 Floors Book collection Study areas Elliptical in Section “Circular” in Plan Design Concept Above Forum: 1st level of stacks Design Concept Above Forum: 2nd level of stacks Design Concept Above Forum: 3rd level of stacks Design Concept Above Forum: 4th level of stacks Design Concept Above Forum: 5th level of stacks Choice of structural material Reinforced Hybrid Steel- Steel structure Concrete with four large steel concrete structure structure trusses supporting the With concrete up to steel With external 16 sloped third floor of spheroid, trusses beam –column concealed in the Laterally tied at lower second floor. three spheroid by post- tensioned beams. •Factors influencing the choice of Reinforced Concrete construction •Increasing rate of steel and extensive use of steel in the truss. nd •Reduced flexibility of space at 2 level of the spheroid. -

A Visit to the Dr. Seuss Archives at UC San Diego Janet Weber Tigard Public Library

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CommonKnowledge Volume 17 , Number 1 Library Wonders and Wanderings: Travels Near and Far (Spring 2011) | Pages 4 July 2014 A Visit to the Dr. Seuss Archives at UC San Diego Janet Weber Tigard Public Library Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.pacificu.edu/olaq Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Weber, J. (2014). A Visit to the Dr. Seuss Archives at UC San Diego. OLA Quarterly, 17(1), 4. http://dx.doi.org/10.7710/ 1093-7374.1308 © 2014 by the author(s). OLA Quarterly is an official publication of the Oregon Library Association | ISSN 1093-7374 | http://commons.pacificu.edu/olaq A Visit to the Dr. Seuss Archives at UC San Diego by Janet Weber bout ten years ago when I was conducting research on Dr. Seuss, I discovered that [email protected] his archives were housed at the University of California San Diego (UCSD) in La Youth Services Librarian Jolla. Since then I’ve wanted to go visit the collection. Little did I know that my dream Tigard Public Library A to visit would come true many years later as a member of the Association for Library Service to Children (ALSC) Special Collections and Bechtel Fellowship Committee. My committee had the opportunity to visit the Dr. Seuss archives during ALA Midwinter in January 2011. Dr. Seuss, also known as Theodore Geisel, was a long time resident of La Jolla up until For more information on his death in 1991. -

Special Collections & Archives' Ledger Art Books Serve As Hands

UC SAN DIEGO THE LIBRARY LIBRARY BLOG Blog Home Page Special Collections & Archives’ Ledger Art Books Serve as Hands-On Learning Tool for Graduate Students February 28, 2018, 9:25 AM “Driving the Horses” plate from the Koba-Russell Sketchbook. Courtesy of: Plains Ledger Art Digital Publishing Project (PILA). The beauty of Indian Ledger Art isn’t just about depicting Native American history in vibrant colors and powerful compositions, but how it has influenced the next generation of Native American artists. To Dwayne Wilcox, it’s more than artwork. It connects him to his Native American culture and reaffirms his purpose in the community. Wearing black pants, a striped dress shirt that hangs loose on his frame, and his signature pork pie hat, Wilcox stands in front of an audience speaking softly about his art and gazing earnestly at the Ledger Art drawings in his exhibit. Dwayne Wilcox The Lakota Ledger artist met with students and spoke in November at a public gathering hosted by the Library in celebration of Native American Heritage Month. A small collection of Wilcox’s contemporary ledger artwork was on view in an exhibition called Teíč’iȟ iŋla: Practicing Decolonial Love, curated by UC San Diego graduate students. Wilcox was joined by Ross Frank, associate professor of ethnic studies and director of the Plains Indian Ledger Art project (PILA). Due to increased collector interest, more nineteenth-century ledger books are coming to light. However, sheets are sold individually for thousands of dollars, dispersing them on the market. In the last few years academics have been trying to reassemble book pages. -

Fall• Winter 2020 Volume 39, No 2 La Jolla Historical Society

FALL• WINTER 2020 VOLUME 39, NO 2 LA JOLLA HISTORICAL SOCIETY MISSION The La Jolla Historical Society inspires and empowers the community to make La Jolla’s diverse past a relevant part of contemporary life. VISION The La Jolla Historical Society looks toward the future while celebrating the past. We preserve and share La Jolla’s distinctive f there is one thing on virtual programs, delivered online or by chaparral and entered from roads off old many years later she felt compelled to put sense of place and encourage quality in the urban built a global pandemic social media. We had a very successful Virtual environment. The Society serves as a thriving community Highway 101, it was a little-known setting her memories in a book. “My physical ties resource and gathering place where residents and visitors provides, it’s perspective, Garden Party on August 22, which you can view where a group of isolated scientists and were cut when I went away to college,” she explore history, art, ideas and culture. I quickly dispatching any on our YouTube channel, and we’re extremely geneticists studied and planted varieties of noted, “but as I write about my youth I BOARD OF DIRECTORS 2018-2019 notions of community grateful to Board members Meg Davis and agricultural crops to improve flavor, disease realize how my sense of self. .was shaped isolation and neutrality Lucy Jackson for their leadership in organizing Suzanne Sette, President resistance and ability to be shipped long by unique experiences of living on The Matthew Mangano, Vice President from the global order. -

Moving Beachwood Forward

March 2020 MOVING BEACHWOOD FORWARD COVER STORY: This is an exciting time for Beachwood, with large and small projects on the horizon that will significantly impact the lives of people who live, work, and visit our city. Mayor Martin S. Horwitz and City Council President James Pasch discuss their goals. March 2020 n Beachwood Buzz 1 EXPECT TO BE SURPRISED At Blu, the Restaurant “Isn’t it Time you Tried that Bottle?” Wine Monday All bottles under $100 at 50% off • 4:00-9:30 p.m. “Did you say Oysters and Champagne, Darling?” Thursday $1 oysters • 4:00-9:30 p.m. • Raw Bar/Main Bar “Haven’t I Seen you Before?” Daily Happy Hours Select spirits and food specials • 4:00-6:00 p.m. • Exclusively at our Main Bar AND “You’veintroducing... Honestly Never Found Anything that Comes Close” Sunday Brunch 10:30 a.m.-2:30 p.m. At Rosso, Italia Molto Bene Wine Wednesdays All bottles under $100 at 50% off • 5:30-9:30 p.m. blutherestaurant.com // 216.831.5599 rosso-italia.com // 216.831.1004 3355 Richmond Road // Beachwood Corner of Chagrin and Richmond 2 Beachwood Buzz n March 2020 Letter from THE EDITOR EXPECT TO BE By Debby Zelman Rapoport hen I sat down to write this column, my overall frame of mind was in need of a lift. I did an online search to find a topic that SURPRISED Wspoke to me and would be relevant for March, stumbled across a listing that included Dr. Seuss’s birthday on March 2, and went with it. -

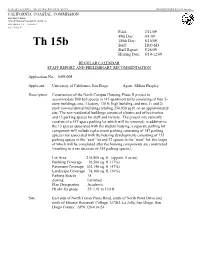

Application No. 6-09-08 (UCSD Student Housing, San Diego)

STATE OF CALIFORNIA -- THE NATURAL RESOURCES AGENCY ARNOLD SCHWARZENEGGER, Governor CALIFORNIA COASTAL COMMISSION SAN DIEGO AREA 7575 METROPOLITAN DRIVE, SUITE 103 SAN DIEGO, CA 92108-4421 (619) 767-2370 Filed: 2/11/09 49th Day: 4/1/09 180th Day: 8/10/09 Th 15b Staff: LRO-SD Staff Report: 5/28/09 Hearing Date: 6/10-12/09 REGULAR CALENDAR STAFF REPORT AND PRELIMINARY RECOMMENDATION Application No.: 6-09-008 Applicant: University of California, San Diego Agent: Milton Phegley Description: Construction of the North Campus Housing Phase II project to accommodate 800 bed spaces in 145 apartment units consisting of four 5- story buildings, one, 13-story, 130 ft. high building, and two, 1- and 2- story non-residential buildings totaling 250,950 sq.ft. on an approximately site. The non-residential buildings consist of a bistro and office/market and 15 parking spaces for staff and visitors. The project site currently consists of a 557-space parking lot which will be removed; in addition to the 15 spaces associated with the student housing, a separate parking lot component will include replacement parking consisting of 187 parking spaces (not associated with the housing development) consisting of 155 parking spaces in the “east” lot and 32 spaces in the “west” lot; the larger of which will be completed after the housing components are constructed (resulting in a net decrease of 355 parking spaces). Lot Area 216,800 sq. ft. (approx. 5 acres) Building Coverage 36,500 sq. ft. (17%) Pavement Coverage 102,140 sq. ft. (47%) Landscape Coverage 78,160 sq. -

Primordial Synthesis of Amines and Amino Acids in a 1958 Miller H2 S

Primordial synthesis of amines and amino acids in a 1958 Miller H2S-rich spark discharge experiment Eric T. Parkera,1, Henderson J. Cleavesb, Jason P. Dworkinc, Daniel P. Glavinc, Michael Callahanc, Andrew Aubreyd, Antonio Lazcanoe, and Jeffrey L. Badaa,2 aGeosciences Research Division, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California at San Diego, 8615 Kennel Way, La Jolla, CA 92093; bGeophysical Laboratory, Carnegie Institution of Washington, 5251 Broad Branch Road NW, Washington, DC 20015; cNational Aeronautics and Space Administration Goddard Space Flight Center, Solar System Exploration Division, Greenbelt, MD 20771; dNational Aeronautics and Space Administration Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, 4800 Oak Grove Drive, Pasadena, CA 91109; and eFacultad de Ciencias, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Apdo. Postal 70-407 Ciudad Universitaria, 04510 Mexico D.F., Mexico Edited by Gerald F. Joyce, The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA, and approved February 14, 2011 (received for review December 22, 2010) Archived samples from a previously unreported 1958 Stanley Miller known volcanic apparatus were found to contain a wide variety of electric discharge experiment containing hydrogen sulfide (H2S) amino acids and amines, including ornithine, homoserine, methy- were recently discovered and analyzed using high-performance lamine, and ethylamine, many of which had not been reported liquid chromatography and time-of-flight mass spectrometry. We previously in spark discharge experiments (7). The volcanic report here the detection and quantification of primary amine- apparatus differed from Miller’s classic apparatus in that it uti- containing compounds in the original sample residues, which were lized an aspirator that injected steam into the electric discharge produced via spark discharge using a gaseous mixture of H2S, CH4, chamber, simulating a volcanic eruption (1). -

The Dr.Seuss Collection Free

FREE THE DR.SEUSS COLLECTION PDF Dr. Seuss,Rik Mayall | none | 21 Oct 2002 | HarperCollins Publishers | 9780007157051 | English | London, United Kingdom The Dr. Seuss Collection Seuss, have entertained and educated children and their parents for over half a century. In fabricating tales and bringing fantastic creatures to life in the The Dr.Seuss Collection of young and old alike, he has given us the likes of the Cat in the Hat, Gertrude McFuzz, Yertle the Turtle, the Grinch, and the Lorax; we now have places to go like Solla Sollew, Who-ville and Sala-ma-Sond. His style of flamboyant, colorful illustrations, surreal surroundings, and clever yet simple rhymes has made his work recognizable throughout the world. These creations are fun, but with a The Dr.Seuss Collection purpose. They teach reading, self-confidence, and the wonderful possibilities of our imaginations. Because of the fragility of the materials in the Seuss Collection, access to the collection is restricted The Dr.Seuss Collection researchers who have previously obtained permission from the director of special collections. Items from the collection are usually on exhibit during the summer session and during the month of March Dr. Seuss's birthday. Please consult the list of exhibits for more details. UC San Diego's Dr. Seuss Collection The Dr.Seuss Collection original drawings, sketches, proofs, notebooks, manuscript drafts, books, audio- and videotapes, photographs, and memorabilia. The approximately 8, items in the collection document the full range of Dr. Seuss's creative achievements, beginning in with his high school activities and ending with his death in Included are early student writings, drawings and class notes; commercial art for Standard Oil of New Jersey, Ford Motor and other companies; stories and illustrations published in Judge Magazine, Red Book Magazine, The Saturday Evening Post, and other popular magazines of the s and s; anti-fascist political cartoons published chiefly in PM; U. -

Geisel Library Building Guide

GEISEL LIBRARY BUILDING GUIDE Stay connected lib.ucsd.edu/subscribe Support the library lib.ucsd.edu/give Share your experience @ucsdgeisel @ucsdlibrary @ucsdlibrary WELCOME TO UC SAN DIEGO’S GEISEL LIBRARY Designed by renowned architect William Pereira in 1970, this campus landmark was named for Audrey and Theodor Seuss Geisel — better known as Dr. Seuss — in 1995. The building’s Brutalist architecture conveys the idea that powerful and permanent hands are holding aloft knowledge itself, which was Pereira’s stated intention. Pereira is also known for works such as the Transamerica Pyramid in San Francisco, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), and rocket-launching facilities at Cape Canaveral. In 1992, underground space on the east and west sides of the building was designed by Latvian-American architect Gunnar Birkerts. Birkerts deliberately designed this addition to be subordinate to the strong, geometrical form of the existing structure. Known for using angular forms, folding planes and light-suffused interiors, Birkerts’ addition provided extra space while preserving the building’s original silhouette and ensuring ample natural light to the lower floors. This guide shares many of the spaces, services, and collections found within this iconic campus building. Staff at Geisel Library’s service desk can answer questions that might arise during your visit. You are welcome to explore floors 1 and 2; floors 4 – 8 in the tower are reserved for quiet study. Theodor Seuss Geisel Memorial (2004) lib.ucsd.edu/about-geisel N 2 3 WELCOME John Baldessari installation (2001) Alexis Smith’s Snake Path (1992) 5 Art Installations near Geisel Library 1 1 On the building’s west side, on the third-level concrete forum (up the external stairs outside the main entrance), is a life-size bronze statue of Theodor Seuss Geisel.