Strain Gauge Measurement – a Tutorial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MGM's Jawaharlal Nehru Engineering College

MGM’s Jawaharlal Nehru Engineering College Laboratory Manual Electrical Power Transmission & Distribution For Second Year (EEP) Students Manual made by Prof. P.A. Gulbhile AuthorJNEC,Aurangabad. FORWARD It is my great pleasure to present this laboratory manual for second year EEP engineering students for the subject of Electrical Power Transmission & Distribution. Keeping in view the vast coverage required for visualization of concepts of Electrical Power Transmission with simple language. As a student, many of you may be wondering with some of the questions in your mind regarding the subject and exactly what has been tried is to answer through this manual. Faculty members are also advised that covering these aspects in initial stage itself, will greatly relieved the minfuture as much of the load will be taken care by the enthusiasm energies of the students once they are conceptually clear. H.O.D. LABORATORY MANNUAL CONTENTS This manual is intended for the second year students of Electrical Electronics & Power engineering branch in the subject of Electrical Power Transmission & Distribution. This manual typically contains practical/Lab Sessions related layouts, sheets of different parts in electrical power transmission & distribution system as well as study of different models of transmission line, measurement of parameters of transmission line and various aspects related the subject to enhance understanding. Although, as per the syllabus, only descriptive treatment is prescribed ,we have made the efforts to cover various aspects of electrical Power Transmission & Distribution subject covering types of different transmission lines , their circuit diagrams and phasor diagrams, electrical design of overhead transmission line , electrical design of overhead transmission line, elaborative understandable concepts and conceptual visualization. -

Physics 517/617 Experiment 1 Instrumentation and Resistor Circuits

Physics 517/617 Experiment 1 Instrumentation and Resistor Circuits 1) Study the operation of the oscilloscope, multimeter, power supplies, and wave generator. For the oscilloscope you should try to understand the function of all the knobs or buttons on the front panel. Some buttons may have several functions and some of the functions will not be relevant for this class. Try to follow the examples in p. 38-42 of the instruction manual. 2) Verify Ohm’s law by measuring and then plotting voltage vs. current for a resistor. Fit your graph(s) to extract the measured resistance. Use a resistor of your choice. Repeat the measurement with a resistor of a much higher value (e.g. 10-100X) than your previous choice. Use a DC power supply for the circuit. 3) Measure the DC resistance of your multimeter (on voltage scale) using a resistor divider, which consists of two resistors in series with one of them being the multimeter resistor. How does your measurement of the multimeter’s resistance compare to the specs of the meter? Note: You do not need to measure the current in this experiment. 4) The RMS (Root Mean Square) value of a voltage (or current) is defined as t 1 2 VRMS = Ú V dt t 0 Show that VRMS = V0 / 2 for a sine wave voltage, V = V0 sinwt. Note: The multimeter only measures the RMS value of a voltage or current. † 5)† This exercise is intended to make you† familiar with some of the very useful functions of the oscilloscope. Send a 1 kHz sine wave with an amplitude of 1 V and DC offset of 1 V into the scope. -

Realization of AC Bridges Using Labview. Details: Explanation

Realization of AC Bridges Using LabView. Introduction: AC Bridges are used to measure the values of unknown resistance, inductance, and capacitance. Although, AC bridges are believed to be very convenient and provides accurate result of the measurement. The construction of the bridges is very simple. The bridge has four arms, one AC supply source and the balance detector. It works on the principle that the balance ratio of the impedances will give the balance condition to the circuit which is determined by the null detector. The bridges have four arms, two have non-inductive resistance and the other two have inductances with negligible resistance. Software Used: LabView LabVIEW is essentially a graphical programming language (technically it’s a development environment, and the language is “G”, but in common usage it’s a language). Instead of typing words like with C++,Python, or other text-based languages, you place and connect visual objects around your screen. Using LABVIEW the AC bridges can be Solved at an ease with proper visualization and insights. The graphical programming approach enables us to build or Solve AC bridges for different number of applications such as measuring the frequency of the audio signals, filtration of undesirable signals etc. Details: AC Bridges that have been analyzed using LabView are: (1) Maxwell’s Inductance Bridge. (2) DeSauty’s Capacitance Bridge. (3) Wheatstone’s Resistance Bridge. Explanation: Maxwell’s Inductance Bridge: A Maxwell bridge is a modification to a Wheatstone bridge used to measure an unknown inductance in terms of calibrated resistance and inductance or resistance and capacitance. Let us consider w=314, Let us consider E to be a constant (let it be 100V). -

Department of Physics Second Allied Physics Iii

KUNTHAVAI NAACHIYAR GOVERNMENT ARTS COLLEGE FOR WOMEN, THANJAVUR. DEPARTMENT OF PHYSICS SECOND ALLIED PHYSICS III 18K4CHAP3 UNIT - I 1. Dr. S. SNEGA, DEPARTMENT OF PHYSICS, THANJAVUR. UNIT - II 2. Dr. N. GEETHA, DEPARTMENT OF PHYSICS, THANJAVUR. UNIT-III 3. Ms. D.S. VASANTHI DEPARTMENT OF PHYSICS, THANJAVUR. UNIT-I: CURRENT ELECTRICITY AND NUCLEAR PHYSICS Kirchhoff’s law –Wheatstone’s bridge – Metre Bridge – Carey foster’s bridge – Measurement of specific resistance – Potentiometer – Calibration of low range voltmeter Nucleus – Nuclear Size – Charge – Mass and Spin – Shell Model – Nuclear fission and fusion – Liquid drop model – Binding energy – Mass defect KIRCHHOFF’S RULES Ohm’s law is useful only for simple circuits. For more complex circuits, Kirchhoff ’s rules can be used to find current and voltage. There are two generalized rules: i) Kirchhoff ’s current rule ii) Kirchhoff ’s voltage rule. Kirchhoff’s first rule (Current rule or Junction rule) It states that the algebraic sum of the currents at any junction of a circuit is zero. It is a statement of conservation of electric charge. All charges that enter a given junction in a circuit must leave that junction since charge cannot build up or disappear at a junction. Current entering the junction is taken as positive and current leaving the junction is taken as negative. I1 + I2 – I3 – I4 – I5 = 0 (or) I1 + I2 = I3 + I4 + I5 Kirchhoff’s Second rule (Voltage rule or Loop rule) It states that in a closed circuit the algebraic sum of the products of the current and resistance of each part of the circuit is equal to the total emf included in the circuit. -

I INVESTIGATION of METHODS for DETECTING NEEDLE INSERTION INTO BLOOD VESSELS by Ehsan Qaium BS in Mechanical Engineering, Virgi

INVESTIGATION OF METHODS FOR DETECTING NEEDLE INSERTION INTO BLOOD VESSELS by Ehsan Qaium BS in Mechanical Engineering, Virginia Tech, 2012 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Swanson School of Engineering in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Mechanical Engineering University of Pittsburgh 2018 i UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH SWANSON SCHOOL OF ENGINEERING This thesis was presented by Ehsan Bin Qaium It was defended on April 19,2018 and approved by William Clark, PhD, Professor Jeffrey Vipperman, PhD, Professor Cameron Dezfulian, MD, Associate Professor Thesis Advisor: William Clark, PhD, Professor ii Copyright © by Ehsan Qaium 2018 iii INVESTIGATION OF METHODS FOR DETECTING NEEDLE INSERTION INTO BLOOD VESSELS Ehsan Qaium, M.S. University of Pittsburgh, 2018 Peripheral intravenous IV (pIV) placement is the mainstay for providing therapies in modern medicine. Although common, approximately 107 million difficult pIV placements each year require multiple attempts to establish IV access. Delays in establishing IV access lead to increased patient pain, delayed administration of life saving medicine, and increased cost to the institution. Current solutions involve using visual vein finders, ultrasounds and a central line if peripheral IV insertion attempts fail. The objective of this study was to investigate methods by which entry into a blood vessel could be detected, and to design and test a novel medical device that increases the likelihood of successful pIV placement on the first attempt. Two types of measurement methods (static and transient) were investigated in this study. Static measurement involved measurements performed with a multimeter and a Wheatstone bridge. The multimeter measurement was unsuccessful due to the effect of polarization. -

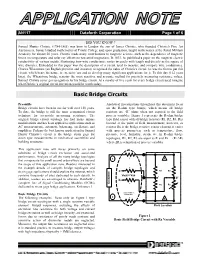

Basic Bridge Circuits

AN117 Dataforth Corporation Page 1 of 6 DID YOU KNOW ? Samuel Hunter Christie (1784-1865) was born in London the son of James Christie, who founded Christie's Fine Art Auctioneers. Samuel studied mathematics at Trinity College and, upon graduation, taught mathematics at the Royal Military Academy for almost 50 years. Christie made many contributions to magnetic science, such as the dependence of magnetic forces on temperature and solar ray effects on terrestrial magnetism. In 1833, he published a paper on the magneto-electric conductivity of various metals, illustrating how wire conductance varies inversely with length and directly as the square of wire diameter. Embedded in this paper was the description of a circuit used to measure and compare wire conductance. Charles Wheatstone (an English physicist and inventor) recognized the value of Christie's circuit; he was the first to put this circuit, which bears his name, to extensive use and to develop many significant applications for it. To this day (162 years later), the Wheatstone bridge remains the most sensitive and accurate method for precisely measuring resistance values. Samuel Christie never got recognition for his bridge circuit. At a royalty of five cents for every bridge circuit used, imagine what Christie’s original circuit invention would be worth today. Basic Bridge Circuits Preamble Analytical investigations throughout this document focus Bridge circuits have been in use for well over 150 years. on the R-ohm type bridge, which means all bridge To date, the bridge is still the most economical circuit resistors are “R” ohms when not exposed to the field technique for accurately measuring resistance. -

Shunt Calibration of Strain Gage Instrumentation

MICRO-MEASUREMENTS Strain Gages and Instruments Tech Note TN-514 Shunt Calibration of Strain Gage Instrumentation I. Introduction the gage. Furthermore, the electrical contacts for inserting the resistor can introduce a significant uncertainty in The need for calibration arises frequently in the use the resistance change. On the other hand, decreasing of strain gage instrumentation. Periodic calibration is the resistance of a bridge arm by shunting with a larger required, of course, to assure the accuracy and/or linearity resistor offers a simple, potentially accurate means of of the instrument itself. More often, calibration is necessary simulating the action of a strain gage. This method, known to scale the instrument sensitivity (by adjusting gage factor as shunt calibration, places no particularly severe tolerance or gain) in order that the registered output correspond requirements on the shunting resistor, and is relatively conveniently and accurately to some predetermined input. insensitive to modest variations in contact resistance. It is An example of the latter situation occurs when a strain also more versatile in application and generally simpler to gage installation is remote from the instrument, with implement. measurable signal attenuation due to leadwire resistance. In this case, calibration is used to adjust the sensitivity Because of its numerous advantages, shunt calibration is of the instrument so that it properly registers the strain the normal procedure for verifying or setting the output signal produced by the gage. Calibration is also used to set of a strain gage instrument relative to a predetermined the output of any auxiliary indicating or recording device mechanical input at the sensor. -

CHAPTER-7 Underground Cables

CHAPTER-7 Underground Cables Construction of Underground Cables: Fig.shows the general Construction of Underground Cables. The various parts are : Cores or Conductors: A cable may have one or more than one core (conductor) depending upon the type of service for which it is intended. For instance, the 3-conductor cable shown in Fig. 11.1 is used for 3- phase service. The conductors are made of tinned copper or aluminium and are usually stranded in order to provide flexibility to the cable. Insulation: Each core or conductor is provided with a suitable thickness of insulation, the thickness of layer depending upon the voltage to be withstood by the cable. The commonly used materials for insulation are impregnated paper, varnished cambric or rubber mineral compound. Metallic sheath: In order to protect the cable from moisture, Conductor gases or other damaging liquids (acids or alkalies) in the soil and atmosphere, a metallic sheath of lead or aluminium is provided over the insulation as shown in Fig. 11.1 Bedding: Over the metallic sheath is applied a layer of bedding which consists of a fibrous material like jute or hessian tape. The purpose of bedding is to protect the metallic sheath against corrosion and from mechanical injury due to armouring. Armouring: Over the bedding, armouring is provided which consists of one or two layers of galvanised steel wire or steel tape. Its purpose is to protect the cable from mechanical injury while laying it and during the course of handling. Armouring may not be done in the case of some cables. Serving: In order to protect armouring from atmospheric conditions, a layer of fibrous material (like jute) similar to bedding is provided over the armouring. -

Applying the Wheatstone Bridge Circuit by Karl Hoffmann

Applying the Wheatstone Bridge Circuit by Karl Hoffmann W1569-1.0 en Applying the Wheatstone Bridge Circuit by Karl Hoffmann Contents: 1 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................1 2 Elementary circuits with strain gages..........................................................................................5 2.1 Measurements on a tension bar..............................................................................................6 2.2 Measurements on a bending beam.........................................................................................7 2.3 Measurements on a twisted shaft ...........................................................................................8 3 Analysis and compensation of superimposed stresses, e.g. tension bar with bending moment .........................................................................................................................................10 4 Compensation of interference effects, especially temperature effects....................................14 5 Compensation of the influence of lead resistances. ..................................................................17 6 Table on different circuit configurations ..................................................................................20 7 Some remarks on the limits of the compensation of interference effects ...............................22 8 The linearity error of the Wheatstone bridge circuit...............................................................23 -

A Conversion of Wheatstone Bridge to Current-Loop Signal Conditioning for Strain Gages

https://ntrs.nasa.gov/search.jsp?R=19970024858 2020-06-16T02:20:48+00:00Z View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by NASA Technical Reports Server NASA Technical Memorandum 104309 A Conversion of Wheatstone Bridge to Current-Loop Signal Conditioning For Strain Gages Karl F. Anderson NASA Dryden Flight Research Center Edwards, California 1995 National Aeronautics and Space Administration Dryden Flight Research Center Edwards, California 93523-0273 A CONVERSION OF WHEATSTONE BRIDGE TO CURRENT-LOOP SIGNAL CONDITIONING FOR STRAIN GAGES Karl F. Anderson* NASA Dryden Flight Research Center P. O. Box 273 Edwards, California 93523-0273 ABSTRACT Alcal current change through the gage during calibration, A Current loop circuitry replaced Wheatstone bridge cir- gage current, A cuitry to signal-condition strain gage transducers in more than 350 data channels for two different test programs at Iref reference resistance current, A NASA Dryden Flight Research Center. The uncorrected J circuit board jack test data from current loop circuitry had a lower noise level than data from comparable Wheatstone bridge circuitry, JP circuit board jumper were linear with respect to gage-resistance change, and OUT were uninfluenced by varying lead-wire resistance. The output current loop channels were easier for the technicians to set OVP over-voltage protection up, verify, and operate than equivalent Wheatstone bridge R resistors on the circuit card channels. Design choices and circuit details are presented in this -

Tech Tip 60602

www.iotech.com TECHTIP 60602 Basic Strain Measurements using IOtech DAQ Hardware INTRODUCTION DISCUSSION Strain gages are sensing devices used in a variety of physical test and STRAIN MEASUREMENT CONFIGURATIONS measurement applications. They change resistance at their output Wheatstone Bridge terminals when stretched or compressed. Because of this character- To make an accurate strain measurement, extremely small resis- istic, the gages are typically bonded to the surface of a solid material tance changes must be measured. The Wheatstone bridge circuit is and measure its minute dimensional changes when put in com- widely used to convert the gage’s microstrain into a voltage change pression or tension. Strain gages and strain gage principles are often that can be fed to the input of the analog-to-digital converter used in devices for measuring acceleration, pressure, tension, and (ADC). (See Figure 1.). When all four resistors in the bridge are force. Strain is a dimensionless unit, defined as a change in length absolutely equal, the bridge is perfectly balanced and V = 0. But per unit length. For example, if a 1-m long bar stretches to 1.000002 out when any one or more of the resistors change value by only a m, the strain is defined as 2 microstrains. Strain gages have a fractional amount, the bridge produces a significant, measurable characteristic gage factor, defined as the fractional change in voltage. When used with an instrument, a strain gage replaces one resistance divided by the strain. For example, 2 microstrain applied or more of the resistors in the bridge, and as the strain gage to a gage with gage factor of 2 produces a fractional resistance undergoes dimensional changes (because it is bonded to a test change of (2x2)10-6 = 4x10-6, or 4 . -

A Low-Voltage Current-Mode Wheatstone Bridge Using CMOS Transistors

World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology International Journal of Electronics and Communication Engineering Vol:5, No:10, 2011 A Low-Voltage Current-Mode Wheatstone Bridge using CMOS Transistors Ebrahim Farshidi However, the need for low-voltage/low-power CMOS analog Abstract—This paper presents a new circuit arrangement for a circuits is growing due to the downscaling of CMOS current-mode Wheatstone bridge that is suitable for low-voltage processes and also, in many situations, particularly in the integrated circuits implementation. Compared to the other proposed mixed analog-digital systems, it is desirable to implement the circuits, this circuit features severe reduction of the elements number, circuits in the MOS technology [12]. low supply voltage (1V) and low power consumption (<350uW). In addition, the circuit has favorable nonlinearity error (<0.35%), In this paper, a new CMWB design to overcome the above operate with multiple sensors and works by single supply voltage. problems is presented [13]. The circuit is designed in CMOS The circuit employs MOSFET transistors, so it can be used for technology, which exhibits flexible characteristics with standard CMOS fabrication. Simulation results by HSPICE show respect to other CM or VM devices, Its main features are high performance of the circuit and confirm the validity of the reducing circuit elements, area efficient implementation, proposed design technique. operation in single supply voltage, current output signal and possibility of low-voltage and low-power due to the fact that Keywords—Wheatstone bridge, current-mode, low-voltage, MOS transistors are employed. MOS. The paper is organized as follows. In section 2, basic I.