The Gems of Jazz

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Where to Study Jazz 2019

STUDENT MUSIC GUIDE Where To Study Jazz 2019 JAZZ MEETS CUTTING- EDGE TECHNOLOGY 5 SUPERB SCHOOLS IN SMALLER CITIES NEW ERA AT THE NEW SCHOOL IN NYC NYO JAZZ SPOTLIGHTS YOUNG TALENT Plus: Detailed Listings for 250 Schools! OCTOBER 2018 DOWNBEAT 71 There are numerous jazz ensembles, including a big band, at the University of Central Florida in Orlando. (Photo: Tony Firriolo) Cool perspective: The musicians in NYO Jazz enjoyed the view from onstage at Carnegie Hall. TODD ROSENBERG FIND YOUR FIT FEATURES f you want to pursue a career in jazz, this about programs you might want to check out. 74 THE NEW SCHOOL Iguide is the next step in your journey. Our As you begin researching jazz studies pro- The NYC institution continues to evolve annual Student Music Guide provides essen- grams, keep in mind that the goal is to find one 102 NYO JAZZ tial information on the world of jazz education. that fits your individual needs. Be sure to visit the Youthful ambassadors for jazz At the heart of the guide are detailed listings websites of schools that interest you. We’ve com- of jazz programs at 250 schools. Our listings are piled the most recent information we could gath- 120 FIVE GEMS organized by region, including an International er at press time, but some information might have Excellent jazz programs located in small or medium-size towns section. Throughout the listings, you’ll notice changed, so contact a school representative to get that some schools’ names have a colored banner. detailed, up-to-date information on admissions, 148 HIGH-TECH ED Those schools have placed advertisements in this enrollment, scholarships and campus life. -

September 1995

Features CARL ALLEN Supreme sideman? Prolific producer? Marketing maven? Whether backing greats like Freddie Hubbard and Jackie McLean with unstoppable imagination, or writing, performing, and producing his own eclectic music, or tackling the business side of music, Carl Allen refuses to be tied down. • Ken Micallef JON "FISH" FISHMAN Getting a handle on the slippery style of Phish may be an exercise in futility, but that hasn't kept millions of fans across the country from being hooked. Drummer Jon Fishman navigates the band's unpre- dictable musical waters by blending ancient drum- ming wisdom with unique and personal exercises. • William F. Miller ALVINO BENNETT Have groove, will travel...a lot. LTD, Kenny Loggins, Stevie Wonder, Chaka Khan, Sheena Easton, Bryan Ferry—these are but a few of the artists who have gladly exploited Alvino Bennett's rock-solid feel. • Robyn Flans LOSING YOUR GIG AND BOUNCING BACK We drummers generally avoid the topic of being fired, but maybe hiding from the ax conceals its potentially positive aspects. Discover how the former drummers of Pearl Jam, Slayer, Counting Crows, and others transcended the pain and found freedom in a pink slip. • Matt Peiken Volume 19, Number 8 Cover photo by Ebet Roberts Columns EDUCATION NEWS EQUIPMENT 100 ROCK 'N' 10 UPDATE 24 NEW AND JAZZ CLINIC Terry Bozzio, the Captain NOTABLE Rhythmic Transposition & Tenille's Kevin Winard, BY PAUL DELONG Bob Gatzen, Krupa tribute 30 PRODUCT drummer Jack Platt, CLOSE-UP plus News 102 LATIN Starclassic Drumkit SYMPOSIUM 144 INDUSTRY BY RICK -

Reggie Workman Working Man

APRIL 2018—ISSUE 192 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM REGGIE WORKMAN WORKING MAN JIM JONNY RICHARD EDDIE McNEELY KING WYANDS JEFFERSON Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East APRIL 2018—ISSUE 192 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 New York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : JIM Mcneely 6 by ken dryden [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : JONNY KING 7 by donald elfman General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The COver : REGGIE WORKMAN 8 by john pietaro Advertising: [email protected] Encore : RICHARD WYANDS by marilyn lester Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest WE Forget : EDDIE JEFFERSON 10 by ori dagan [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : MINUS ZERO by george grella US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or vOXNEWS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] Obituaries by andrey henkin Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Stuart Broomer, FESTIvAL REPORT Robert Bush, Thomas Conrad, 13 Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, CD REviews 14 Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Marilyn Lester, Suzanne -

By David Kunian, 2013 All Rights Reserved Table of Contents

Copyright by David Kunian, 2013 All Rights Reserved Table of Contents Chapter INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................... 1 1. JAZZ AND JAZZ IN NEW ORLEANS: A BACKGROUND ................ 3 2. ECONOMICS AND POPULARITY OF MODERN JAZZ IN NEW ORLEANS 8 3. MODERN JAZZ RECORDINGS IN NEW ORLEANS …..................... 22 4. ALL FOR ONE RECORDS AND HAROLD BATTISTE: A CASE STUDY …................................................................................................................. 38 CONCLUSION …........................................................................................ 48 BIBLIOGRAPHY ….................................................................................... 50 i 1 Introduction Modern jazz has always been artistically alive and creative in New Orleans, even if it is not as well known or commercially successful as traditional jazz. Both outsiders coming to New Orleans such as Ornette Coleman and Cannonball Adderley and locally born musicians such as Alvin Battiste, Ellis Marsalis, and James Black have contributed to this music. These musicians have influenced later players like Steve Masakowski, Shannon Powell, and Johnny Vidacovich up to more current musicians like Terence Blanchard, Donald Harrison, and Christian Scott. There are multiple reasons why New Orleans modern jazz has not had a greater profile. Some of these reasons relate to the economic considerations of modern jazz. It is difficult for anyone involved in modern jazz, whether musicians, record -

Spring Season Brings All That Jazz

Tulane University Spring Season Brings All That Jazz April 25, 2008 1:00 AM Kathryn Hobgood [email protected] This spring brings a bustle of activity for jazz musicians at Tulane University. In addition to multiple performances at the famous New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival, campus musicians students as well as more experienced jazzmen on the faculty have a whole lot going on. John Doheny, a professor of practice, plays sax while Jim Markway, a tutor in the Newcomb Department of Music, plays bass in the Professors of Pleasure jazz quintet. (Photo by Kathryn Hobgood) This week, the Tulane Jazz Orchestra will be busy with several appearances. On Tuesday (April 29), the orchestra will have its end-of-semester concert at 8 p.m. in Dixon Theatre. Smaller jazz combos will perform on Wednesday (April 30) beginning at 6 p.m. in Dixon Recital Hall. And on Friday (May 2), the orchestra will perform on the Gentilly Stage at the New Orleans Jazzfest at 11:35 a.m. Tulane students are the musicians in the Tulane Jazz Orchestra. The orchestra is directed by John Doheny, a professor of practice in the Newcomb Department of Music, who is extra busy this season. Doheny teaches jazz theory, history and applied private lessons, in addition to directing the student jazz ensembles. He also is a working musician. A project that came to fruition for Doheny recently was the Tulane faculty jazz quintet's first CD. Dubbing themselves the “Professors of Pleasure,” the quintet features Doheny on saxophone; John Dobry, a professor of practice, on guitar; Jim Markway on bass; and Kevin O'Day on drums. -

The Bad Ass Pulse by Martin Longley

December 2010 | No. 104 Your FREE Monthly Guide to the New York Jazz Scene aaj-ny.com The THE Bad Ass bad Pulse PLUS Mulgrew Miller • Microscopic Septet • Origin • Event Calendar Many people have spoken to us over the years about the methodology we use in putting someone on our cover. We at AllAboutJazz-New York consider that to be New York@Night prime real estate, if you excuse the expression, and use it for celebrating those 4 musicians who have that elusive combination of significance and longevity (our Interview: Mulgrew Miller Hall of Fame, if you will). We are proud of those who have graced our front page, lamented those legends who have since passed and occasionally even fêted 6 by Laurel Gross someone long deceased who deserved another moment in the spotlight. Artist Feature: Microscopic Septet But as our issue count grows and seminal players are fewer and fewer, we must expand our notion of significance. Part of that, not only in the jazz world, has by Ken Dryden 7 been controversy, those players or groups that make people question their strict On The Cover: The Bad Plus rules about what is or what is not whatever. Who better to foment that kind of 9 by Martin Longley discussion than this month’s On The Cover, The Bad Plus, only the third time in our history that we have featured a group. This tradition-upending trio is at Encore: Lest We Forget: Village Vanguard from the end of December into the first days of January. 10 Bill Smith Johnny Griffin Another band that has pushed the boundaries of jazz, first during the ‘80s but now with an acclaimed reunion, is the Microscopic Septet (Artist Feature). -

Downloaded PDF File of the Original First-Edi- Pete Extracted More Music from the Song Form of the Chart That Adds Refreshing Contrast

DECEMBER 2016 VOLUME 83 / NUMBER 12 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Managing Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Markus Stuckey Circulation Manager Kevin R. Maher Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes Editorial Intern Izzy Yellen ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian, Michael Weintrob; North Carolina: Robin -

Joseph "Smokey" * No

JOSEPH "SMOKEY" * NO. 2009-CA-0739 JOHNSON AND WARDELL QUEZERGUE * COURT OF APPEAL VERSUS * FOURTH CIRCUIT TUFF-N-RUMBLE * MANAGEMENT, INC., STATE OF LOUISIANA BOUTIT, INC., DBA NO LIMIT * * * * * * * RECORDS, PRIORITY RECORDS LLC, AND SONY MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT, INC. APPEAL FROM CIVIL DISTRICT COURT, ORLEANS PARISH NO. 2002-6935, DIVISION “N-8” Honorable Ethel Simms Julien, Judge * * * * * * Judge Edwin A. Lombard * * * * * * (Court composed of Judge Charles R. Jones, Judge James F. McKay, III, Judge Edwin A. Lombard) Gregory P. Eveline EVELINE DAVIS & PHILLIPS 5811 Tchoupitoulas Street New Orleans, LA 70115 -AND- Ashlye M. Keaton LAW OFFICE OF ASHLYE M. KEATON, ESQ. 818 Howard Avenue Suite 300 New Orleans, LA 70113 COUNSEL FOR PLAINTIFFS/APPELLEES Edgar D. Gankendorff Christophe B. Szapary PROVOSTY & GANKENDORFF, L.L.C. 650 Poydras Street Suite 2700 New Orleans, LA 70130 COUNSEL FOR DEFENDANT/APPELLANT, TUFF-N-RUMBLE MANAGEMENT, INC. AFFIRMED This appeal filed by Tuff-N-Rumble Management d/b/a Tuff City Records (Tuff City) is from the judgment of the trial court granting the plaintiffs’ motion for partial summary judgment. After de novo review, the judgment of the trial court is affirmed. Relevant Facts and Procedural History The matter arises out of a copyright dispute over “It Ain’t My Fault,” a song co-written in 1964 by two legendary New Orleans musicians, Mr. Joseph “Smokey” Johnson and Dr.1 Wardell Quezergue a/ka/ the “Creole Beethoven.” The song was subsequently incorporated into work by a rap artist in the 1990s without payment to the musicians and, as a result, the musicians filed a federal lawsuit in 1999 against Tuff City, as well as Vyshon Miller a/k/a Silkk the Shocker, No Limit of New Orleans, LLC, Big P Music, LLC, No Limit Productions, LLC, and Boutit, Inc. -

The Evolution of New Orleans Drumming

Gretna Middle School Concert and Clinic The Evolution of New Orleans Drumming Featuring: Allyn Robinson and Jason Mingledorff Wednesday, April 24, 2013 The Evolution of New Orleans Drumming Band Members Original Brass Bands – 1870-1900 Allyn Robinson Drums Just A Closer Walk With Thee – The Original Brass Jason Mingledorff Saxophone Bands provided the traditional slow funeral march. Charlie Halloran Trombone Over In The Glory Land – An upbeat musical celebration of life was followed by the 2nd Line Anthony Brown Guitar marchers. Donald Ramsey Bass Blues, Jazz & Swing – 1900-1950 New Orleans Drumming Pioneers Bourbon Street Parade – The birth of the drum set brought Baby Dodds from the 2nd Line parades Warren “Baby” Dodds 1898-1959 to the dance halls. Paul Barbarin 1899-1969 R&B and Rock‘N Roll – 1950-1965 Earl Palmer 1924-2008 Lucille – Earl Palmer, the father of the backbeat, lays the foundation for modern pop music. Ed Blackwell 1929-1992 Funk & Latin – 1960-1980 Charles “Hungry” Williams 1935-1986 Hey Pocky A-Way – The Meters bring the 2nd Line Joseph “Smokey” Johnson 1936-Present beat to modern popular music. James Black 1940-1988 Cissy Strut – Joseph “Zigaboo” Modeliste mixes traditional New Orleans grooves and syncopated Joseph “Zigaboo” Modeliste 1948-Present Latin rhythms into a Funk gumbo. A Special Thank You - Modern Brass Bands – 1970-Present To Cheryl Fryer, the Gretna Middle School Administration Li’l Liza Jane – Carrying on the New Orleans and all of the Students: Thank you for allowing us to be a tradition, the new brass-band movement updated part of your day and to share our love of New Orleans the parading rhythms to the current trends in Music. -

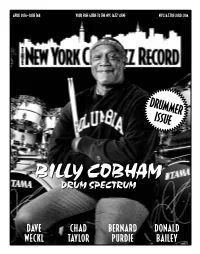

Drummerissue

APRIL 2016—ISSUE 168 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM drumMER issue BILLYBILLY COBHAMCOBHAM DRUMDRUM SPECTRUMSPECTRUM DAVE CHAD BERNARD DONALD WECKL TAYLOR PURDIE BAILEY Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East APRIL 2016—ISSUE 168 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 New York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : Dave Weckl 6 by ken micallef [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : Chad Taylor 7 by ken waxman General Inquiries: [email protected] On The Cover : Billy Cobham 8 by john pietaro Advertising: [email protected] Encore : Bernard Purdie by russ musto Editorial: 10 [email protected] Calendar: Lest We Forget : Donald Bailey 10 by donald elfman [email protected] VOXNews: LAbel Spotlight : Amulet by mark keresman [email protected] 11 Letters to the Editor: [email protected] VOXNEWS 11 by suzanne lorge US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 In Memoriam 12 by andrey henkin International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or money order to the address above FESTIVAL REPORT or email [email protected] 13 Staff Writers CD Reviews 14 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Fred Bouchard, Stuart Broomer, Thomas Conrad, Miscellany 36 Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Philip Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Event Calendar Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, 38 Alex Henderson, Marcia Hillman, Terrell Holmes, Robert Iannapollo, Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Ken Micallef, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, As we head into spring, there is a bounce in our step. -

BJ1362. Moonoogian, George. the King of Sax: the Best of BJ1379

Biographical Entries: J 539 BJ1362. Moonoogian, George. The King of Sax: The Best of BJ1379. Anon. Robert Johnson Complete: Piano, Voice, Plas Johnson. Austria: Wolf WBJ 021, 1996. Guitar. Milwaukee: Hal Leonard, 2004. 216 pp.; London: Music Sales, 2004. 216 pp. BJ1363. Trageser, Jim. “Johnson, Plas,” in Encyclopedia of the Blues. Vol. 1: A–J, ed. E. Komara, pp. 535–536 BJ1380. Anon. “Robert Johnson Film Fiasco.” Jefferson no. (Item E162). 119 (1999): 25. BJ1364. Wilmer, Val. “Plas: Rhythm of the Tenor.” Melody BJ1381. Anon. Robert Johnson: King of the Delta Blues. Maker (11 Sep 1976): 42. London: Immediate Music, 1969. 61 pp. See also: Bulletin du Hot Club de France no. 404 BJ1382. Anon. “Robert Johnson, 1911–1938.” Guitar World (1992): 2+. Goldmine no. 89 (Oct 1983). Now Dig 18, no. 7 (Jul 1998): 206. This no. 215 (Feb 2001). BJ1383. Anon. “The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame: Forefa- ROBERT JOHNSON (c1916–) thers.” Rolling Stone no. 467 (13 Feb 1986): 48. BJ1365. Mitchell, George. “Robert Johnson,” in Blow My BJ1384. Anon. “Roots of Rhythm and Blues: The Robert Blues Away, pp. 131–151. Baton Rouge: Louisiana Johnson Era,” in 1991 Festival of American Folklife, State University Press, 1971. June 28–July 1, July 4–July 7. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Inst., 1991. ROBERT JOHNSON BJ1385. Anon. “Searching for Robert Johnson.” JazzTimes BJ1366. Kochakian, Dan; Karampatsos, John ‘Bunky’. “Rob- 20, no. 5 (May 1990): 31–32. ert Johnson: New Hampshire Bluesman.” Whiskey, Women, and ... no. 6 (Mar 1974): 15. BJ1386. Anon. “Searching for Robert Johnson Records.” Discoveries no. 106 (1997): 22. -

Terence Higgins Drummer Percussionist

TERENCE HIGGINS DRUMMER PERCUSSIONIST BIO New Orleans is known for its great music and culture, and it is also known for spawning some of greatest In The Bywater is named after the neighborhood in which the CD was recorded, one of the most historic drummers in the world. Every serious drummer has been influenced by New Orleans style drumming at in New Orleans. Just down the Mississippi River from the French Quarter, Bywater's colorful, diverse some point in there development. With a unique blend of slinky street beats, New Orleans funk, R&B, history seeps through into the sounds contained on the disc. But with that history comes a marked Zydeco, blues, traditional jazz, and swing, gives New Orleans Drummers that thang!!!.....But don't get it modern slant full of synthetic sounds and forward-thinking musical interplay. Higgins is joined by many of twisted, "New Orleans style of drumming is not method book friendly, it’s all about the feel of it, it’s a his NOLA compatriots here, including sibling keyboard and sax players (Andy and Scott) with the feeling thing and its part of the fabric of New Orleans". impossibly Cajun surname of Bourgeois. Also featured on the album are DDBB guitar craftsman Jamie McLean, trombonist Sammy Williams, bassist Calvin Turner (Jason Crosby, Marc Broussard), and noted Terence was born in New Orleans in 1970 and was raised in the suburb of old Algiers. He was introduced funk guitarist Renard Poche. Together they display the stuff that makes New Orleans music not only to the drums at a very young age by his great grandfather and he has been playing ever since.