Queering Gay Male Body Dissatisfaction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lynn Ludwig Photographs Collection, 1988-1998

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8x92bwj No online items Finding aid to the Lynn Ludwig Photographs Collection, 1988-1998 Finding aid prepared by Tim Wilson James C. Hormel Gay & Lesbian Center, San Francisco Public Library 100 Larkin Street San Francisco, CA, 94102 (415) 557-4400 [email protected] 2012 Finding aid to the Lynn Ludwig GLC 65 1 Photographs Collection, 1988-1998 Title: Lynn Ludwig Photographs Collection, Date (inclusive): 1988-1998 Collection Identifier: GLC 65 Creator: Ludwig, Lynn Physical Description: 41 scrapbooks + circa 200 encapsulated photographs in 3 oversized boxes(25.0 cubic feet) Contributing Institution: James C. Hormel Gay & Lesbian Center, San Francisco Public Library 100 Larkin Street San Francisco, CA 94102 (415) 557-4567 [email protected] Abstract: Portraits and informal photographs of gay bears, gay bear events, Ludwig family and events, holidays, Northern California scenery and locations. There are some flyers included in the albums, as well as attendance name badges. Physical Location: The collection is stored onsite. Language of Materials: Collection materials are in English. Access The collection is available for use during San Francisco History Center hours, with photographs available during Photo Desk hours. Collections that are stored offsite should be requested 48 hours in advance. Publication Rights Copyright retained by Lynn Ludwig. All requests for permission to publish or quote from manuscripts must be submitted in writing to the City Archivist. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Lynn Ludwig Photographs Collection (GLC 65), Gay and Lesbian Center, San Francisco Public Library. Provenance Donated by Lynn Ludwig, June 2010. Biographical note Lynn Ludwig is a gay photographer based in the San Francisco Bay area. -

Leatherwalk Aims to Keep SF Kinky Organizers of This Year's Leatherwalk Are Challenging Participants to Ensure San Francisco Doesn't Lose Its Sexually Subversive Ways

LeatherWalk aims to keep SF kinky Organizers of this year's LeatherWalk are challenging participants to ensure San Francisco doesn't lose its sexually subversive ways. The theme of the 25th annual fundraiser for a trio of local nonprofits is "Keep San Francisco Kinky." The official start to the city's Leather Week, the stroll through several gay neighborhoods will take place Sunday, September 18. The first walk was held in 1992 by Art Tomaszewski, a former AIDS Emergency Fund board president and former Bare Chest Calendar man and Mr. Headquarters Leather. In 2001, Sandy "Mama" Reinhardt, a longtime leather community member and fundraiser, took over production of the walk. Lance Holman, who has been a longtime walk volunteer for AEF and its sister organization the Breast Cancer Emergency Fund, assumed leadership of the walk in 2013. Last year Folsom Street Events, which produces the Folsom Street Fair, set to take place Sunday, September 25, and other parties and fairs, partnered with AEF/BCEF to put on the LeatherWalk in an effort to boost participation and increase the amount of money raised. Folsom Street Events is again taking a leadership role this year in organizing the walk, with the money raised again benefiting itself and the two emergency funds. AEF last month merged with Positive Resource Center, while BCEF is becoming its own standalone entity. The goal this year is to raise $20,000 through the walk. "We walk together to celebrate leather, kink, family and community - all while raising funds for three great agencies," noted Folsom Street Events in an email announcing this year's event. -

Homophobia and Transphobia Exist

Homophobia and Transphobia Exist. These forms of oppression can be enacted, even unintentionally, by English language arts teachers through their instruction, curriculum, and classroom policies at all grade levels. LGBTQ+- affirming teachers consciously work to create a welcoming learning environment for all students. Thus, as members of the National Council of Teachers of English, we recognize that teachers work toward this environment when they Acknowledge that coming out is a continual process, and support students and colleagues as they explore and affirm their identities as lesbian, gay, bisexual, pansexual, asexual, queer, transgender, nonbinary, and other gender and sexual minority identities (LGBTQ+). Recognize that LGBTQ+ people exist in all communities and have intersectional identities. Racism, xenophobia, classism, ableism, sexism, and other forms of oppression impact LGBTQ+ communities. Cultivate classroom materials and libraries that reflect the racial, ethnic, economic, ability, geographic, religious, and linguistic diversity within LGBTQ+ communities. Include reading and writing opportunities that reflect the experiences of LGBTQ+ communities, including literary works, informational articles, and multimedia texts. Seek learning opportunities, both professional and informal, to develop their understanding of LGBTQ+ topics in education. Challenge practices and policies that censor, deny, or dehumanize LGBTQ+ students, educators, families, and communities. Avoid dividing students into “boys” and “girls” and avoid other activities and language that treat gender as binary and assume everyone identifies with a gender. Advocate for the creation and support of LGBTQ+-affirming spaces in their schools. These spaces might include a Genders and Sexualities Equality Alliance, Gay-Straight/Queer-Straight Alliance, or Gender- Expansive Youth Club. Honor the experiences, stories, and accomplishments of LGBTQ+ people year-round, and beyond their coming out stories. -

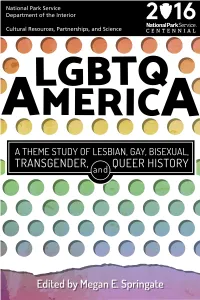

LGBTQ America: a Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History Is a Publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service

Published online 2016 www.nps.gov/subjects/tellingallamericansstories/lgbtqthemestudy.htm LGBTQ America: A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History is a publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service. We are very grateful for the generous support of the Gill Foundation, which has made this publication possible. The views and conclusions contained in the essays are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government. © 2016 National Park Foundation Washington, DC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted or reproduced without permission from the publishers. Links (URLs) to websites referenced in this document were accurate at the time of publication. PLACES Unlike the Themes section of the theme study, this Places section looks at LGBTQ history and heritage at specific locations across the United States. While a broad LGBTQ American history is presented in the Introduction section, these chapters document the regional, and often quite different, histories across the country. In addition to New York City and San Francisco, often considered the epicenters of LGBTQ experience, the queer histories of Chicago, Miami, and Reno are also presented. QUEEREST28 LITTLE CITY IN THE WORLD: LGBTQ RENO John Jeffrey Auer IV Introduction Researchers of LGBTQ history in the United States have focused predominantly on major cities such as San Francisco and New York City. This focus has led researchers to overlook a rich tradition of LGBTQ communities and individuals in small to mid-sized American cities that date from at least the late nineteenth century and throughout the twentieth century. -

Queer Alchemy: Fabulousness in Gay Male Literature and Film

QUEER ALCHEMY QUEER ALCHEMY: FABULOUSNESS IN GAY MALE LITERATURE AND FILM By ANDREW JOHN BUZNY, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Andrew John Buzny, August 2010 MASTER OF ARTS (2010) McMaster University' (English) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: Queer Alchemy: Fabulousness in Gay Male Literature and Film AUTHOR: Andrew John Buzny, B.A. (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Professor Lorraine York NUMBER OF PAGES: v, 124pp. 11 ABSTRACT This thesis prioritizes the role of the Fabulous, an underdeveloped critical concept, in the construction of gay male literature and film. Building on Heather Love's observation that queer communities possess a seemingly magical ability to transform shame into pride - queer alchemy - I argue that gay males have created a genre of fiction that draws on this alchemical power through their uses of the Fabulous: fabulous realism. To highlight the multifarious nature of the Fabulous, I examine Thomas Gustafson's film Were the World Mine, Tomson Highway's novel Kiss ofthe Fur Queen, and Quentin Crisp's memoir The Naked Civil Servant. 111 ACKNO~EDGEMENTS This thesis would not have reached completion without the continuing aid and encouragement of a number of fabulous people. I am extremely thankful to have been blessed with such a rigorous, encouraging, compassionate supervisor, Dr. Lorraine York, who despite my constant erratic behaviour, and disloyalty to my original proposal has remained a strong supporter of this project: THANK YOU! I would also like to thank my first reader, Dr. Sarah Brophy for providing me with multiple opportunities to grow in~ellectually throughout the past year, and during my entire tenure at McMaster University. -

UPPER MARKET AREAS November 27Th

ANNUAL EVENTS International AIDS Candlelight Memorial About Castro / Upper Market 3rd Sunday in May Harvey Milk Day May 22nd Frameline Film Festival / S.F. LGBT International Film Festival June, www.frameline.org S.F. LGBT Pride/Pink Saturday Last weekend in June www.sfpride.org / www.thesisters.org Leather Week/Folsom Street Fair End of September www.folsomstreetevents.org Castro Street Fair 1st Sunday in October HISTORIC+LGBT SIGHTS www.castrostreetfair.org IN THE CASTRO/ Harvey Milk & George Moscone Memorial March & Candlelight Vigil UPPER MARKET AREAS November 27th Film Festivals throughout the year at the iconic Castro Theatre www.castrotheatre.com Castro/Upper Market CBD 584 Castro St. #336 San Francisco, CA 94114 P 415.500.1181 F 415.522.0395 [email protected] castrocbd.org @visitthecastro facebook.com/castrocbd Eureka Valley/Harvey Milk Memorial Branch Library and Mission Dolores (AKA Mission San Francisco de Asis, The Best of Castro / Upper Market José Sarria Court (1 José Sarria Court at 16th and 320 Dolores St. @ 16th St.) Built between 1785 and Market Streets) Renamed in honor of Milk in 1981, the library 1791, this church with 4-foot thick adobe walls is the oldest houses a special collection of GLBT books and materials, and building in San Francisco. The construction work was done by Harvey Milk Plaza/Giant Rainbow Flag (Castro & Harvey Milk’s Former Camera Shop (575 Castro St.) Gay often has gay-themed history and photo displays in its lobby. Native Americans who made the adobe bricks and roof tiles Market Sts) This two-level plaza has on the lower level, a activist Harvey Milk (1930-1978) had his store here and The plaza in front of the library is named José Sarria Court in by hand and painted the ceiling and arches with Indian small display of photos and a plaque noting Harvey Milk’s lived over it. -

Providing Culturally and Clinically Competent Care for 2SLGBTQ Seniors: Inclusion, Diversity and Equity

Providing Culturally and Clinically Competent Care for 2SLGBTQ Seniors: Inclusion, Diversity and Equity Devan Nambiar, MSc. Acting Program Manger & Education & Training Facilitator E: [email protected] October 22, 2019 2 LT outcomes Group Norms • Give yourself permission to make • Create practical steps to inclusive and safe spaces for SOGI mistakes & have a process to -Deconstruct your address mistakes • Understand 2SLGBTQ+ health disparities ideology, values, • Use “I” statements beliefs systems • Use correct pronouns (he, she, • Competencies in clinical, cultural safety, from religions, cultural humility attitude, morality and they….) implicit biases • Agree to disagree • Become an ally • Create safe space for all to learn -Being comfortable with not knowing • Respect confidentiality and questioning your • Share wisdom & Share airtime discomfort with SOGI 3 SOGI-sexual orientation and gender identity 4 Trans Mentorship Call biweekly -1st & 3rd week on Wednesday 12 noon -1 pm Must register 5 online 6 1 Does Discussions Myths on 2SLGBTQ heterosexuality end at senior • At school, either college and/ or university have you learnt about LGBT2SQ age? clients or in population health? • When did you decide you are heterosexual? How do you know you are 100% heterosexual? • You stop being 2SLGBTQ if you are older, a senior, • Are you familiar with gender neutral pronouns? retired, have an illness • Are there staff who are out at work as LGBT2SQ? • Do you know LGBT2SQ people outside work? • • Have you done an assessment for HRT? -

![Nancy Tucker T-Shirt Collection, 1975-[2014]GLC 25](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1532/nancy-tucker-t-shirt-collection-1975-2014-glc-25-891532.webp)

Nancy Tucker T-Shirt Collection, 1975-[2014]GLC 25

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8vq3604 No online items Nancy Tucker T-Shirt Collection, 1975-[2014]GLC 25 Finding aid prepared by Tim Wilson James C. Hormel Gay & Lesbian Center, San Francisco Public Library 100 Larkin Street San Francisco, CA, 94102 (415) 557-4400 [email protected] 2015 Nancy Tucker T-Shirt Collection, GLC 25 1 1975-[2014]GLC 25 Title: Nancy Tucker T-Shirt Collection, Date (inclusive): 1975-[2014] Date (bulk): 1980-1995 Collection Identifier: GLC 25 Creator: Tucker, Nancy Physical Description: 4.0 boxes(100.0 items) Contributing Institution: James C. Hormel Gay & Lesbian Center, San Francisco Public Library 100 Larkin Street San Francisco, CA, 94102 (415) 557-4400 [email protected] Abstract: These shirts were produced to commemorate gay and lesbian parades, marches, gatherings, organizations, and AIDS-related groups or events. Some subjects include San Francisco's Lesbian and Gay Freedom Day Parades and Celebrations, the San Francisco International Lesbian and Gay Film Festival, Queer Nation, the Gay Games, and FrontRunners. Physical Location: The collection is stored onsite. Language of Materials: Collection materials are in English. Access The collection is available for use during San Francisco History Center hours, with photographs available during Photo Desk hours. Collections that are stored offsite should be requested 48 hours in advance. Publication Rights All requests for permission to publish or quote from manuscripts must be submitted in writing to the City Archivist. Permission for publication is given on behalf of the San Francisco Public Library as the owner of the physical items. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Nancy Tucker T-shirt collection (GLC 25), Gay and Lesbian Center, San Francisco Public Library. -

The Newest Generation Leading the Gay Civil Rights

Bay Area LGBTQ+ Millennials: The Newest Generation Leading the Gay Civil Rights Movement A Dissertation by Sara Hall-Kennedy Brandman University Irvine, California School of Education Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education in Organizational Leadership March 2020 Committee in charge: Tamerin Capellino, Ed.D., Committee Chair Carol Holmes Riley, Ed.D. Donald B. Scott, Ed.D. Bay Area LGBTQ+ Millennials: The Newest Generation Leading the Gay Civil Rights Movement Copyright © 2020 by Sara Hall-Kennedy iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you first and foremost to my love, my wife and life partner, Linnea Kennedy, for your endless support, guidance, and wisdom throughout this journey. I am and will be forever grateful for your love. You unselfishly believed in me through one of the most challenging points in your life, and that will always be a part of fulfilling this degree. Thank you to my chair, Dr. C. Your strength and resilience are truly inspiring. I appreciate the two years that you have dedicated to supporting me in this journey. There is no one else I would have been able to travel this road with. You empowered me and resemble the leader that I aspire to become. You were absolutely the best choice. Thank you to my committee members, Dr. Scott and Dr. Riley. Your expertise and input enabled me to make thoughtful decisions throughout this process. Your vision and guidance were exactly what I needed to survive this journey. I appreciate you for taking the time to support me and being patient with me over the last two years. -

Halperin David M Traub Valeri

GAY SHAME DAVID M. HALPERIN & VALERIE TRAUB I he University of Chicago Press C H I C A G 0 A N D L 0 N D 0 N david m. h alperin is theW. H. Auden Collegiate Professor of the History and Theory of Sexuality at the University of Michigan. He is the author of several books, including Saint Foucault: Towards a Gay Hagiography (Oxford University Press, 1995) and, most re cently, What Do Gay Men Want? An Essay on Sex, Risk, and Subjectivity (University of Michi gan Press, 2007). valerie traub is professor ofEnglish andwomen's studies at the Uni versity of Michigan, where she chairs the Women's Studies Department. She is the author of Desire and Anxiety: Circulations of Sexuality in Shakesptanan Drama (Routledge, 1992) and The Renaissance of Ltsbianism in Early Modem England (Cambridge University Press, 2002). The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2009 by The University of Chicago Al rights reserved. Published 2009 Printed in the United States of America 17 16 15 14 13 12 ii 10 09 1 2 3 4 5 ISBN-13: 978-0-226-31437-2 (cloth) ISBN-13: 978-0-226-31438-9 (paper) ISBN-10: 0-226-31437-5 (cloth) ISBN-10: 0-226-31438-3 (paper) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gay shame / [edited by] David M. Halperin and Valerie Traub. p.cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-226-31437-2 (cloth: alk. paper) isbn-10: 0-226-31437-5 (cloth: alk. -

Gay Shame in a Geopolitical Context

Gay shame in a geopolitical context Article (Accepted Version) Munt, Sally R (2018) Gay shame in a geopolitical context. Cultural Studies, 33 (2). pp. 223-248. ISSN 0950-2386 This version is available from Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/73415/ This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies and may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the URL above for details on accessing the published version. Copyright and reuse: Sussex Research Online is a digital repository of the research output of the University. Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable, the material made available in SRO has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk Gay Shame in a Geopolitical Context Sally R Munt Sussex Centre for Cultural Studies, University of Sussex, Brighton, UK Email: [email protected] Postal address: School of Media, Film and Music, Silverstone Building, University of Sussex, Falmer, Brighton, UK BN1 9RG Sally R Munt is Professor of Gender and Cultural Studies at the University of Sussex, UK. -

Femalemasculi Ni Ty

FEMALE MASCULINITY © 1998 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper oo Designed by Amy Ruth Buchanan Frontispiece: Sadie Lee, Raging Bull (1994) Typeset in Scala by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. FOR GAYAT RI CONTENTS Illustrations ix Preface xi 1 An Introduction to Female Masculinity: Masculinity without Men r 2 Perverse Presentism: The Androgyne, the Tribade, the Female Husband, and Other Pre-Twentieth-Century Genders 45 3 "A Writer of Misfits": John Radclyffe Hall and the Discourse of Inversion 7 5 4 Lesbian Masculinity: Even Stone Butches Get the Blues nr 5 Transgender Butch: Butch/FTM Border Wars and the Masculine Continuum 141 6 Looking Butch: A Rough Guide to Butches on Film 175 7 Drag Kings: Masculinity and Performance 231 viii · Contents 8 Raging Bull (Dyke): New Masculinities 267 Notes 279 Bibliography 307 Filmography 319 Index 323 IL LUSTRATIONS 1 Julie Harris as Frankie Addams and Ethel Waters as Bernice in The Member of the Wedding (1953) 7 2 Queen Latifahas Cleo in Set It Off(19 97) 30 3 Drag king Mo B. Dick 31 4 Peggy Shaw's publicity poster (1995) 31 5 "Ingin," fromthe series "Being and Having," by Catherine Opie (1991) 32 6 "Whitey," fromthe series "Being and Having," by Catherine Opie (1991) 33 7 "Mike and Sky," by Catherine Opie (1993) 34 8 "Jack's Back II," by Del Grace (1994) 36 9 "Jackie II," by Del Grace (1994) 37 10 "Dyke," by Catherine Opie (1992) 39 11 "Self-