The Prince De Ligne. His Memoirs, Letters, and Miscellaneous Papers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dick Tracy.” MAX ALLAN COLLINS —Scoop the DICK COMPLETE DICK ® TRACY TRACY

$39.99 “The period covered in this volume is arguably one of the strongest in the Gould/Tracy canon, (Different in Canada) and undeniably the cartoonist’s best work since 1952's Crewy Lou continuity. “One of the best things to happen to the Brutality by both the good and bad guys is as strong and disturbing as ever…” comic market in the last few years was IDW’s decision to publish The Complete from the Introduction by Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy.” MAX ALLAN COLLINS —Scoop THE DICK COMPLETE DICK ® TRACY TRACY NEARLY 550 SEQUENTIAL COMICS OCTOBER 1954 In Volume Sixteen—reprinting strips from October 25, 1954 THROUGH through May 13, 1956—Chester Gould presents an amazing MAY 1956 Chester Gould (1900–1985) was born in Pawnee, Oklahoma. number of memorable characters: grotesques such as the He attended Oklahoma A&M (now Oklahoma State murderous Rughead and a 467-lb. killer named Oodles, University) before transferring to Northwestern University in health faddist George Ozone and his wild boys named Neki Chicago, from which he was graduated in 1923. He produced and Hokey, the despicable "Nothing" Yonson, and the amoral the minor comic strips Fillum Fables and The Radio Catts teenager Joe Period. He then introduces nightclub photog- before striking it big with Dick Tracy in 1931. Originally titled Plainclothes Tracy, the rechristened strip became one of turned policewoman Lizz, at a time when women on the the most successful and lauded comic strips of all time, as well force were still a rarity. Plus for the first time Gould brings as a media and merchandising sensation. -

Anthony Tropolle Life of Cicero

ANTHONY TROPOLLE LIFE OF CICERO VOLUME I 2008 – All rights reserved Non commercial use permitted HE LIFE OF CICERO BY ANTHONY TROLLOPE _IN TWO VOLUMES_ VOL. I. CONTENTS OF VOLUME I. CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION. CHAPTER II. HIS EDUCATION. CHAPTER III. THE CONDITION OF ROME. CHAPTER IV. HIS EARLY PLEADINGS.--SEXTUS ROSCIUS AMERINUS.--HIS INCOME. CHAPTER V. CICERO AS QUAESTOR. CHAPTER VI. VERSES. CHAPTER VII. CICERO AS AEDILE AND PRAETOR. CHAPTER VIII. CICERO AS CONSUL. CHAPTER IX. CATILINE. CHAPTER X. CICERO AFTER HIS CONSULSHIP. CHAPTER XI. THE TRIUMVIRATE. CHAPTER XII. HIS EXILE. * * * * * APPENDICES. APPENDIX A. APPENDIX B. APPENDIX C. APPENDIX D. APPENDIX E. THE LIFE OF CICERO. CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION. I am conscious of a certain audacity in thus attempting to give a further life of Cicero which I feel I may probably fail in justifying by any new information; and on this account the enterprise, though it has been long considered, has been postponed, so that it may be left for those who come after me to burn or publish, as they may think proper; or, should it appear during my life, I may have become callous, through age, to criticism. The project of my work was anterior to the life by Mr. Forsyth, and was first suggested to me as I was reviewing the earlier volumes of Dean Merivale's History of the Romans under the Empire. In an article on the Dean's work, prepared for one of the magazines of the day, I inserted an apology for the character of Cicero, which was found to be too long as an episode, and was discarded by me, not without regret. -

U.S. Government Printing Office Style Manual, 2008

U.S. Government Printing Offi ce Style Manual An official guide to the form and style of Federal Government printing 2008 PPreliminary-CD.inddreliminary-CD.indd i 33/4/09/4/09 110:18:040:18:04 AAMM Production and Distribution Notes Th is publication was typeset electronically using Helvetica and Minion Pro typefaces. It was printed using vegetable oil-based ink on recycled paper containing 30% post consumer waste. Th e GPO Style Manual will be distributed to libraries in the Federal Depository Library Program. To fi nd a depository library near you, please go to the Federal depository library directory at http://catalog.gpo.gov/fdlpdir/public.jsp. Th e electronic text of this publication is available for public use free of charge at http://www.gpoaccess.gov/stylemanual/index.html. Use of ISBN Prefi x Th is is the offi cial U.S. Government edition of this publication and is herein identifi ed to certify its authenticity. ISBN 978–0–16–081813–4 is for U.S. Government Printing Offi ce offi cial editions only. Th e Superintendent of Documents of the U.S. Government Printing Offi ce requests that any re- printed edition be labeled clearly as a copy of the authentic work, and that a new ISBN be assigned. For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512-1800; DC area (202) 512-1800 Fax: (202) 512-2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402-0001 ISBN 978-0-16-081813-4 (CD) II PPreliminary-CD.inddreliminary-CD.indd iiii 33/4/09/4/09 110:18:050:18:05 AAMM THE UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE STYLE MANUAL IS PUBLISHED UNDER THE DIRECTION AND AUTHORITY OF THE PUBLIC PRINTER OF THE UNITED STATES Robert C. -

Wine.Kittlehouse Wine List 8.10

! The Story of the Wine Cellar at Crabtree’s Kittle House Restaurant and Inn The year was 1988 and John Crabtree’s idea was to create one of the greatest restaurant wine lists in the world. Grounded in the belief that great winemakers make great wine, we set out to learn who the world’s greatest winemakers were - the talented people making the most compelling and delicious wines of their type, creating the greatest expressions of a special place, the grapes that grow there and that winemaker’s vision of how that wine should taste. When we started our wine journey, the Kittle House wine list had about 150 selections and the wine cellar held a few thousand bottles and took up a small fraction of the space compared to what it is today. Both the list and the cellar grew very fast. We invited winemakers to the Kittle House for winemaker dinners and travelled to meet them on their estates and in their vineyards. We started in California with the wines from legendary producers like Robert Mondavi, Caymus, Groth and Dunn and from the new guard like Marcassin, Peter Michael, Bryant, Colgin and Turley. We then went to France and procured wines from the big boys in Bordeaux and Burgundy – Lafite, Latour, Margaux, Mouton, DRC, Coche-Dury, Leflaive, Dujac and Drouhin. Then we moved on to the Rhone Valley, the Loire, Alsace, Champagne and the rest of France, then on to Italy, Spain, Germany, Austria, Australia, New Zealand and the Pacific Northwest. So many great winemakers, so many great wines! In each place we would ask those great winemakers who, besides them, were making the best wines in the region. -

View of Race and Culture, Winter, 1957

71-27,438 BOSTICK, Herman Franklin, 1929- THE INTRODUCTION OF AFRO-FRENCH LITERATURE AND CULTURE IN THE AMERICAN SECONDARY SCHOOL . CURRICULUM: A TEACHER'S GUIDE. I The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1971 Education, curriculum development. I i ( University Microfilms, A XEROKCompany, Ann Arbor, Michigan ©Copyright by Herman Franklin Bostick 1971 THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED THE INTRODUCTION OF AFRO-FRENCH LITERATURE AND CULTURE IN THE AMERICAN SECONDARY SCHOOL CURRICULUM; A TEACHER'S GUIDE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Herman Franklin Bostick, B.A., M.A. The Ohio State University Approved by College of Education DEDICATION To the memory of my mother, Mrs. Leola Brown Bostick who, from my earliest introduction to formal study to the time of her death, was a constant source of encouragement and assistance; and who instilled in me the faith to persevere in the face of seemingly insurmountable obstacles, I solemnly dedicate this volume. H.F.B. 11 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS To list all of the people who contributed in no small measure to the completion of this study would be impossible in the limited space generally reserved to acknowledgements in studies of this kind. Therefore, I shall have to be content with expressing to this nameless host my deepest appreciation. However, there are a few who went beyond the "call of duty" in their assistance and encouragement, not only in the preparation of this dissertation but throughout my years of study toward the Doctor of Philosophy Degree, whose names deserve to be mentioned here and to whom a special tribute of thanks must be paid. -

The Horse-Breeder's Guide and Hand Book

LIBRAKT UNIVERSITY^' PENNSYLVANIA FAIRMAN ROGERS COLLECTION ON HORSEMANSHIP (fop^ U Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2009 with funding from Lyrasis IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/horsebreedersguiOObruc TSIE HORSE-BREEDER'S GUIDE HAND BOOK. EMBRACING ONE HUNDRED TABULATED PEDIGREES OF THE PRIN- CIPAL SIRES, WITH FULL PERFORMANCES OF EACH AND BEST OF THEIR GET, COVERING THE SEASON OF 1883, WITH A FEW OF THE DISTINGUISHED DEAD ONES. By S. D. BRUCE, A.i3.th.or of tlie Ainerican. Stud Boole. PUBLISHED AT Office op TURF, FIELD AND FARM, o9 & 41 Park Row. 1883. NEW BOLTON CSNT&R Co 2, Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1883, By S. D. Bruce, In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington, D. C. INDEX c^ Stallions Covering in 1SS3, ^.^ WHOSE PEDIGREES AND PERFORMANCES, &c., ARE GIVEN IN THIS WORK, ALPHABETICALLY ARRANGED, PAGES 1 TO 181, INCLUSIVE. PART SECOISTD. DEAD SIRES WHOSE PEDIGREES AND PERFORMANCES, &c., ARE GIVEN IN THIS WORK, PAGES 184 TO 205, INCLUSIVE, ALPHA- BETICALLY ARRANGED. Index to Sires of Stallions described and tabulated in tliis volume. PAGE. Abd-el-Kader Sire of Algerine 5 Adventurer Blythwood 23 Alarm Himvar 75 Artillery Kyrle Daly 97 Australian Baden Baden 11 Fellowcraft 47 Han-v O'Fallon 71 Spendthrift 147 Springbok 149 Wilful 177 Wildidle 179 Beadsman Saxon 143 Bel Demonio. Fechter 45 Billet Elias Lawrence ' 37 Volturno 171 Blair Athol. Glen Athol 53 Highlander 73 Stonehege 151 Bonnie Scotland Bramble 25 Luke Blackburn 109 Plenipo 129 Boston Lexington 199 Breadalbane. Ill-Used 85 Citadel Gleuelg... -

Rabelais' Pantagruel and Gargantua As Instruction Manuals

FROM POPULAR CULTURE TO ENLIGHTENMENT: RABELAIS’ PANTAGRUEL AND GARGANTUA AS INSTRUCTION MANUALS Ashley Robb A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August: 2012: Committee: Dr. Beatrice Guenther, Advisor Dr. Robert Berg ii ABSTRACT Dr. Beatrice Guenther, Advisor Popular references are a defining feature of François Rabelais’ Pantagruel and Gargantua. One cannot read either of these narratives without being exposed to a barrage of popular characters, imagery, and events. This study serves to elucidate Rabelais’ use of popular characters within Pantagruel and Gargantua by arguing that the author used these characters as instructional tools. The first component of this thesis will analyze the manner in which Rabelais makes use of his mythical protagonists in order to denounce the ideological use of myth. This study will also demonstrate how Rabelais uses popular characters in his second narrative, Gargantua, to evoke Erasmian evangelism. The final chapter of this thesis will examine several narrative techniques employed by Rabelais in order to transmit to his readers lessons on wisdom and truth. The culmination of these examples serves to show how Rabelais’ Pantagruel and Gargantua function as instruction manuals, by redefining and reclaiming what it means to be a Christian, and informing readers how to live a better, more evangelical, life. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. -

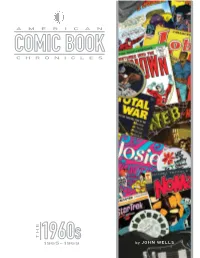

By JOHN WELLS a M E R I C a N C H R O N I C L E S

AMERICAN CHRONICLES THE 1965-1969 by JOHN WELLS Table of Contents Introductory Note about the Chronological Structure of American Comic Book Chronicles ................. 4 Note on Comic Book Sales and Circulation Data.......................................... 5 Introduction & Acknowledgements ............ 6 Chapter One: 1965 Perception................................................................8 Chapter Two: 1966 Caped.Crusaders,.Masked.Invaders.............. 69 Chapter Three: 1967 After.The.Gold.Rush.........................................146 Chapter Four: 1968 A.Hazy.Shade.of.Winter.................................190 Chapter Five: 1969 Bad.Moon.Rising..............................................232 Works Cited ...................................................... 276 Index .................................................................. 285 Perception Comics, the March 18, 1965, edition of Newsweek declared, were “no laughing matter.” However trite the headline may have been even then, it wasn’t really wrong. In the span of five years, the balance of power in the comic book field had changed dramatically. Industry leader Dell had fallen out of favor thanks to a 1962 split with client Western Publications that resulted in the latter producing comics for themselves—much of it licensed properties—as the widely-respected Gold Key Comics. The stuffily-named National Periodical Publications—later better known as DC Comics—had seized the number one spot for itself al- though its flagship Superman title could only claim the honor of -

The Memoirs of AGA KHAN WORLD ENOUGH and TIME

The Memoirs of AGA KHAN WORLD ENOUGH AND TIME BY HIS HIGHNESS THE AGA KHAN, P.C., G.C.S.I., G.C.V.O., G.C.I.E. 1954 Simon and Schuster, New York Publication Information: Book Title: The Memoirs of Aga Khan: World Enough and Time. Contributors: Aga Khan - author. Publisher: Simon and Schuster. Place of Publication: New York. Publication Year: 1954. First Printing Library of Congress Catalogue Card Number: 54-8644 Dewey Decimal Classification Number: 92 MANUFACTURED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BY H. WOLFF BOOK MFG. CO., NEW YORK, N. Y. Publication Information: Book Title: The Memoirs of Aga Khan: World Enough and Time. Contributors: Aga Khan - author. Publisher: Simon and Schuster. Place of Publication: New York. Publication Year: 1954. Publication Information: Book Title: The Memoirs of Aga Khan: World Enough and Time. Contributors: Aga Khan - author. Publisher: Simon and Schuster. Place of Publication: New York. Publication Year: 1954. CONTENTS PREFACE BY W. SOMERSET MAUGHAM Part One: CHILDHOOD AND YOUTH I A Bridge Across the Years 3 II Islam, the Religion of My Ancestors 8 III Boyhood in India 32 IV I Visit the Western World 55 Part Two: YOUNG MANHOOD V Monarchs, Diplomats and Politicians 85 VI The Edwardian Era Begins 98 VIII Czarist Russia 148 VIII The First World War161 Part Three: THE MIDDLE YEARS IX The End of the Ottoman Empire 179 X A Respite from Public Life 204 XI Foreshadowings of Self-Government in India 218 XII Policies and Personalities at the League of Nations 248 Part Four: A NEW ERA XIII The Second World War 289 XIV Post-war Years with Friends and Family 327 XV People I Have Known 336 XVI Toward the Future 347 INDEX 357 Publication Information: Book Title: The Memoirs of Aga Khan: World Enough and Time. -

Liste Des Départements De L'empire Français, Des Provinces

Liste des départements de l’Empire français, des Provinces illyriennes et Royaume d’Italie en 1811-12 N° département chef-lieu 01 Ain Bourg 02 Aisne Laon 03 Allier Moulins 04 Basses-Alpes Digne 05 Hautes-Alpes Gap 85 Alpes-Maritimes Nice 110 Apennins Chiavari 06 Ardèche Privas 07 Ardennes Charleville 08 Ariège Foix 112 Arno Florence 09 Aube Troyes 10 Aude Carcassonne 11 Aveyron Rodez 133 Bouches de l'Èbre Lérida 128 Bouches-de-l'Elbe Hambourg 125 Bouches-de-l'Escaut Middelbourg 120 Bouches-de-l'Yssel Zwolle 119 Bouches-de-la-Meuse La Haye 126 Bouches-du-Rhin Bois-le-Duc 12 Bouches-du-Rhône Marselle 129 Bouches-du-Weser Brême 13 Calvados Caen 14 Cantal Aurillac 15 Charente Angoulême 16 Charente-Inférieure Saintes 17 Cher Bourges 18 Corrèze Tulle 19 Corse Ajaccio 20 Côte-d'Or Dijon 21 Côtes-du-Nord Saint-Brieuc 22 Creuse Guéret 93 Deux-Nèthes Anvers 75 Deux-Sèvres Niort 109 Doire Ivrée 23 Dordogne Périgueux 24 Doubs Besançon 25 Drôme Valence 94 Dyle Bruxelles 123 Ems-Occidental Groningue 124 Ems-Oriental Aurich 130 Ems-Supérieur Osnabruck 92 Escaut Gand 26 Eure Evreux 27 Eure-et-Loir Chartres 28 Finistère Quimper 98 Forêts Luxembourg 122 Frise Leeuwarden 29 Gard Nîmes 30 Haute-Garonne Toulouse 87 Gênes Gênes 31 Gers Auch 32 Gironde Bordeaux 33 Hérault Montpellier 34 Ille-et-Vilaine Rennes 35 Indre Chateauroux 36 Indre-et-Loire Tours 37 Isère Grenoble 86 Jemappes Mons 38 Jura Lons-le-Saunier 39 Landes Mont-de-Marsan 99 Léman Genève 131 Lippe Münster 40 Loir-et-Cher Blois 88 Loire Montbrison 41 Haute-Loire Le Puy 42 Loire-Inférieure Nantes -

Préface Les Grands Notables Dans Les Départements Belges Paul Janssens L'annexion De 1795 À 1815 Des Provinces Belges À La

1 In : Jacques LOGIE, Les grands notables du Premier Empire dans le département de la Dyle (Bruxelles 2013) 8-17 (Fontes Bruxellae 6). Préface Les grands notables dans les départements belges1 Paul Janssens L’annexion de 1795 à 1815 des provinces belges à la France révolutionnaire et impériale nous a laissé quelques précieuses séries de documents concernant les personnalités les plus en vue de l’époque. Citons la contribution militaire de 1794, qui visait indistinctement tous les riches, l’emprunt forcé de l’an IV (1796), beaucoup plus large, les listes d’électeurs faisant partie des collèges électoraux des arrondissements et départements, les listes municipales des 100 citoyens les plus imposés et celles des 600 personnes les plus imposées au niveau départemental. A la base, des assemblées cantonales appelaient au vote tous les citoyens. Mais ce droit de vote accordé à tous avait des effets limités. Les citoyens eux-mêmes n’élisaient aucun représentant. Leur compétence se limitait à désigner des candidats aux fonctions locales. Il incombait aux autorités supérieures d’opérer un choix parmi ceux-ci. Au demeurant, les candidats retenus pour faire partie du conseil municipal devaient tous être inscrits sur la liste des 100 citoyens les plus imposés de la commune. La désignation de candidats pour exercer des fonctions régionales ou nationales était réservée aux collèges électoraux d’arrondissement et de département. Ce corps électoral restreint (entre 120 et 200 personnes par collège d’arrondissement et de 200 à 300 personnes par collège départemental) était désigné à vie par les électeurs cantonaux. Au niveau des arrondissements, leur choix pouvait s’opérer librement, tandis que les membres du collège électoral du département devaient tous faire partie de la liste des 600 contribuables les plus imposés. -

University Microfilms International 300 N

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “ Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted you will find a target note listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in “sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete.