Participation and Performance Trends of 1.2M Runners During Half-Centu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Runtastic Running Season Is Here Final1000px

RUNNING SEASON IS HERE! Temperatures are rising and your activity level should be, too! The good news? There are literally millions of races & events worldwide to keep you focused, motivated and feeling supported. Whether you’d like to give your first 5K a go or you’re looking to set a new marathon PR this year – use the engaging facts & figures below to get inspired, learn about fellow runners in the Runtastic Community and consider what personal challenges (races or otherwise) you might like to commit yourself to this running season. Ready… Set… GO! Statistically, men run START Listening to music their fastest while running can boost marathon at age 27; performance by up to women at 29.1 15%. 2 27 29 0 10 20 30 AGE SCALE The fastest half marathon (female) in the world was run by Florence Jebet Kiplagat in 1:05:12.3 The fastest marathon Male runners (male) in the world was run by covering more than Dennis Kipruto Kimetto in 30 miles 2:02:57.3 a week are likely to conceive girls. 4 In 2013, over 42 million Americans ran six or more days per week.5 44.6 million pairs of running shoes were sold in the United States in 2012, totaling $3.04 billion! 6 The London Marathon is the Guinness World Record's largest annual fundraising event in the world. Since its launch, runners have raised more than £500 million for charity! 7 £ £ The average 10K time for Runtastic users is 56 min. 19 sec. for men and 63 min. -

2010 New York Marathon Statistical Information Men New York Marathon All Time List

2010 New York Marathon Statistical Information Men New York Marathon All Time list Performances Time Performers Name Nat Place Date 1 2:07:43 1 Tesfaye Jifar ETH 1 4 Nov 2001 2 2:08:01 2 Juma Ikangaa TAN 1 5 Nov 1989 3 2:08:07 3 Rodger Rop KEN 1 3 Nov 2002 4 2:08:12 4 John Kagwe KEN 1 2 Nov 1997 5 2:08:17 5 Christopher Cheboiboch KEN 2 3 Nov 2002 6 2:08:20 6 Steve Jones GBR 1 6 Nov 1988 7 2:08:39 7 Laban Kipkemboi KEN 3 3 Nov 2002 8 2:08:43 8 Marilson Gomes dos Santos BRA 1 2 Nov 2008 9 2:08:45 John Kagwe 1 1 Nov 1998 10 2:08:48 9 Joseph Chebet KEN 2 1 Nov 1998 11 2:08:51 10 Zebedayo Bayo TAN 3 1 Nov 1998 12 2:08:53 11 Mohamed Ouaadi FRA 4 3 Nov 2002 13 2:08:59 12 Rod Dixon NZL 1 23 Oct 1983 14 2:09:04 13 Martin Lel KEN 1 5 Nov 2007 15 2:09:07 14 Abderrahim Goumri MAR 2 2 Nov 2008 16 2:09:08 15 Geoff Smith GBR 2 23 Oct 1983 17 2:09:12 16 Stefano Baldini ITA 5 3 Nov 2002 18 2:09:14 Joseph Chebet 1 7 Nov 1999 19 2:09:15 17 Meb Keflezighi USA 1 1 Nov 2009 20 2:09:16 Abderrahim Goumri 2 4 Nov 2007 21 2:09:19 18 Japhet Kosgei KEN 2 4 Nov 2001 22 2:09:20 19 Domingos Castro POR 2 7 Nov 1999 23 2:09:27 Joseph Chebet 2 2 Nov 1997 24 2:09:28 20 Salvador Garcia MEX 1 3 Nov 1991 25 2:09:28 21 Hendrick Ramaala RSA 1 7 Nov 2004 26 2:09:29 22 Alberto Salazar USA 1 24 Oct 1982 27 2:09:29 23 Willie Mtolo RSA 1 1 Nov 1992 28 2:09:30 24 Paul Tergat KEN 1 6 Nov 2005 29 2:09:31 Stefano Baldini 3 2 Nov 1997 30 2:09:31 Hendrick Ramaala 2 6 Nov 2005 31 2:09:32 25 Shem Kororia KEN 3 7 Nov 1999 32 2:09:33 26 Rodolfo Gomez MEX 2 24 Oct 1982 33 2:09:36 27 Giacomo -

Iaaf World Half Marathon Championships Kavarna 2012 Facts & Figures

IAAF WORLD HALF MARATHON CHAMPIONSHIPS KAVARNA 2012 FACTS & FIGURES Incorporating the IAAF World Half Marathon Championships (1992-2005/2008- 2010) & the IAAF World Road Running Championships 2006/2007 Past Championships...............................................................................................1 Past Medallists .......................................................................................................1 Overall Placing Table..............................................................................................5 Most Medals Won...................................................................................................6 Youngest & Oldest..................................................................................................7 Most Appearances by athlete.................................................................................7 Most Appearances by country................................................................................8 Competitorʼs Index ...............................................................................................10 World Road Race Records & Best Performances ...............................................33 Progression of World Record & Best Performances at Half Marathon ................35 KAVARNA 2012 ★ FACTS & FIGURES/PAST CHAMPS & MEDALLISTS 1 PAST CHAMPIONSHIPS –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– These totals have been adjusted from those previously published so that athletes entered for the championships -

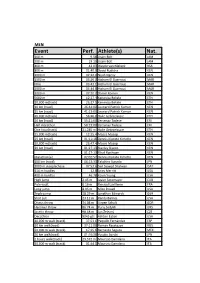

Event Perf. Athlete(S) Nat

MEN Event Perf. Athlete(s) Nat. 100 m 9.58 Usain Bolt JAM 200 m 19.19 Usain Bolt JAM 400 m 43.03 Wayde van Niekerk RSA 800 m 01:40.9 David Rudisha KEN 1000 m 02:12.0 Noah Ngeny KEN 1500 m 03:26.0 Hicham El Guerrouj MAR Mile 03:43.1 Hicham El Guerrouj MAR 2000 m 04:44.8 Hicham El Guerrouj MAR 3000 m 07:20.7 Daniel Komen KEN 5000 m 12:37.4 Kenenisa Bekele ETH 10,000 m(track) 26:17.5 Kenenisa Bekele ETH 10 km (road) 26:44:00 Leonard Patrick Komon KEN 15 km (road) 41:13:00 Leonard Patrick Komon KEN 20,000 m(track) 56:26.0 Haile Gebrselassie ETH 20 km (road) 55:21:00 Zersenay Tadese ERI Half marathon 58:23:00 Zersenay Tadese ERI One hour(track) 21,285 m Haile Gebrselassie ETH 25,000 m(track) 12:25.4 Moses Mosop KEN 25 km (road) 01:11:18 Dennis Kipruto Kimetto KEN 30,000 m(track) 26:47.4 Moses Mosop KEN 30 km (road) 01:27:13 Stanley Biwott KEN 01:27:13 Eliud Kipchoge KEN Marathon[a] 02:02:57 Dennis Kipruto Kimetto KEN 100 km (road) 06:13:33 Takahiro Sunada JPN 3000 m steeplechase 07:53.6 Saif Saaeed Shaheen QAT 110 m hurdles 12.8 Aries Merritt USA 400 m hurdles 46.78 Kevin Young USA High jump 2.45 m Javier Sotomayor CUB Pole vault 6.16 m Renaud Lavillenie FRA Long jump 8.95 m Mike Powell USA Triple jump 18.29 m Jonathan Edwards GBR Shot put 23.12 m Randy Barnes USA Discus throw 74.08 m Jürgen Schult GDR Hammer throw 86.74 m Yuriy Sedykh URS Javelin throw 98.48 m Jan Železný CZE Decathlon 9045 pts Ashton Eaton USA 10,000 m walk (track) 37:53.1 Paquillo Fernández ESP 10 km walk(road) 37:11:00 Roman Rasskazov RUS 20,000 m walk (track) 17:25.6 Bernardo -

START LIST Marathon Men - Final

London World Championships 4-13 August 2017 START LIST Marathon Men - Final RECORDS RESULT NAME COUNTRY AGE VENUE DATE World Record WR 2:02:57 Dennis Kipruto KIMETTO KEN 30 Berlin 28 Sep 2014 Championships Record CR 2:06:54 Abel KIRUI KEN 27 Berlin 22 Aug 2009 World Leading WL 2:03:58 Wilson Kipsang KIPROTICH KEN 35 Tokyo 26 Feb 2017 6 August 2017 10:55 START TIME NAME COUNTRY DATE of BIRTH PERSONAL BEST SEASON BEST Mariano MASTROMARINO ARG 15 Sep 82 2:15:27 Jack COLREAVY AUS 15 Jun 89 2:18:32 2:18:32 Josh HARRIS AUS 3 Jul 90 2:17:08 2:17:08 Brad MILOSEVIC AUS 26 May 89 2:16:00 2:16:24 Valentin PFEIL AUT 17 Jul 88 2:14:50 2:14:50 Abraham NIYONKURU BDI 29 Dec 89 2:16:14 2:16:14 Abdelhadi EL HACHIMI BEL 15 Dec 74 2:10:35 2:26:23 Hassan CHANI BRN 5 May 88 2:14:58 2:14:58 Shumi DECHASA BRN 28 May 89 2:06:43 2:15:35 Eric GILLIS CAN 8 Mar 80 2:11:21 Thomas TOTH CAN 6 Oct 91 2:18:58 2:18:58 Manuel CABRERA CHI 30 Jan 83 2:18:04 2:20:19 Leslie ENCINA CHI 2 Jan 82 2:17:46 2:20:59 Enzo YÁÑEZ CHI 13 Sep 85 2:17:35 2:18:39 Abdi Hakin ULAD DEN 14 Jun 91 2:14:03 Mumin GALA DJI 6 Sep 86 2:13:04 Segundo JAMI ECU 12 May 86 2:17:11 2:18:04 Yohanes GHEBREGERGIS ERI 1 Jan 89 2:08:14 2:08:14 Ghebrezgiabhier KIBROM ERI 1 Feb 87 2:09:36 2:14:52 Amanuel MESEL ERI 29 Dec 90 2:08:17 2:10:44 Iván FERNÁNDEZ ESP 10 Jun 88 2:12:55 Javier GUERRA ESP 10 Nov 83 2:09:33 2:10:55 Ayad LAMDASSEM ESP 11 Oct 81 2:09:28 2:12:30 Roman FOSTI EST 6 Jun 83 2:17:54 2:28:20 Tiidrek NURME EST 18 Nov 85 2:17:59 Tsegaye MEKONNEN ETH 15 Jun 95 2:04:32 2:07:26 Tamirat TOLA ETH 11 Aug 91 -

Half Marathon

IAAF/EDF Energy World Half Marathon Championships 2009 Birmingham Sunday 11 October 2009 Half Marathon WOMEN ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHL START LIST ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC RESULT NAME NAT AGE DATE VENUE WR1:06:25 Lornah KIPLAGAT NED 3314 Oct 2007 Udine CR1:06:47 Paula RADCLIFFE GBR 277 Oct 2001 Bristol WL1:07:00 Mary Jepkosgei KEITANY KEN 275 Sep 2009 Lille 11 October 2009 9:00 BIB NAME NAT YEAR PERSONAL BEST 2009 BEST 10 Cassie FIEN AUS 85 1:12:24 1:12:24 11 Maria Zeferina BALDAIA BRA 72 1:12:45 1:19:22 12 Yingjie LIU CHN 89 13 Maria Sig MØLLER DEN 83 1:13:26 1:13:26 14 Furtuna ZEGERGISH ERI 89 1:09:41 1:09:41 15 Workitu AYANU ETH 87 1:15:03 1:15:03 16 Tirfi TSEGAYE ETH 84 1:13:31 1:13:31 17 Abebu GELAN ETH 90 1:07:57 1:07:57 18 Aberu KEBEDE ETH 89 1:08:43 1:08:43 19 Mestawet TUFA ETH 83 1:13:39 20 Caroline DESPREZ FRA 71 1:14:03 1:17:37 21 Alyson DIXON GBR 78 1:13:40 1:13:40 22 Claire HALLISSEY GBR 83 1:12:03 1:12:03 23 Gemma MILES GBR 80 1:13:13 1:13:13 24 Rebecca ROBINSON GBR 82 1:13:11 1:13:11 25 Michelle ROSS-COPE GBR 72 1:12:35 1:12:35 26 Caitriona JENNINGS IRL 80 1:19:12 1:19:12 28 Ivana IOZZIA ITA 73 1:13:07 1:13:07 29 Emma QUAGLIA ITA 80 1:13:27 30 Yukiko -

Cardiff 2016 F&F

IAAF/Cardiff University WORLD HALF MARATHON CHAMPIONSHIPS FACTS & FIGURES Incorporating the IAAF World Half Marathon Championships (1992-2005/2008-2010-2012-2014) IAAF World Road Running Championships 2006/2007 Past Championships...............................................................................................1 Past Medallists .......................................................................................................1 Overall Placing Table..............................................................................................5 Most Medals Won...................................................................................................6 Youngest & Oldest..................................................................................................7 Most Appearances by athlete.................................................................................7 Most Appearances by country................................................................................8 Country Index .......................................................................................................10 World Road Race Records & Best Performances at 15Km, 20Km & Half Mar .........39 Progression of World Record & Best Performance at 15Km, 20Km & Half Mar .......41 CARDIFF 2016 ★ FACTS & FIGURES/PAST CHAMPS & MEDALLISTS 1 PAST CHAMPIONSHIPS –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– These totals do not include athletes entered for the championships who never started, but teams are counted -

IAAF WORLD RECORDS - MEN As at 1 January 2018 EVENT PERF

IAAF WORLD RECORDS - MEN as at 1 January 2018 EVENT PERF. WIND ATHLETE NAT PLACE DATE TRACK EVENTS 100m 9.58 0.9 Usain BOLT JAM Berlin, GER 16 Aug 09 200m 19.19 -0.3 Usain BOLT JAM Berlin, GER 20 Aug 09 400m 43.03 Wayde van NIEKERK RSA Rio de Janeiro, BRA 14 Aug 16 800m 1:40.91 David Lekuta RUDISHA KEN London, GBR 9 Aug 12 1000m 2:11.96 Noah NGENY KEN Rieti, ITA 5 Sep 99 1500m 3:26.00 Hicham EL GUERROUJ MAR Roma, ITA 14 Jul 98 1 Mile 3:43.13 Hicham EL GUERROUJ MAR Roma, ITA 7 Jul 99 2000m 4:44.79 Hicham EL GUERROUJ MAR Berlin, GER 7 Sep 99 3000m 7:20.67 Daniel KOMEN KEN Rieti, ITA 1 Sep 96 5000m 12:37.35 Kenenisa BEKELE ETH Hengelo, NED 31 May 04 10,000m 26:17.53 Kenenisa BEKELE ETH Bruxelles, BEL 26 Aug 05 20,000m 56:26.0 Haile GEBRSELASSIE ETH Ostrava, CZE 27 Jun 07 1 Hour 21,285 Haile GEBRSELASSIE ETH Ostrava, CZE 27 Jun 07 25,000m 1:12:25.4 Moses Cheruiyot MOSOP KEN Eugene, USA 3 Jun 11 30,000m 1:26:47.4 Moses Cheruiyot MOSOP KEN Eugene, USA 3 Jun 11 3000m Steeplechase 7:53.63 Saif Saaeed SHAHEEN QAT Bruxelles, BEL 3 Sep 04 110m Hurdles 12.80 0.3 Aries MERRITT USA Bruxelles, BEL 7 Sep 12 400m Hurdles 46.78 Kevin YOUNG USA Barcelona, ESP 6 Aug 92 FIELD EVENTS High Jump 2.45 Javier SOTOMAYOR CUB Salamanca, ESP 27 Jul 93 Pole Vault 6.16i Renaud LAVILLENIE FRA Donetsk, UKR 15 Feb 14 Long Jump 8.95 0.3 Mike POWELL USA Tokyo, JPN 30 Aug 91 Triple Jump 18.29 1.3 Jonathan EDWARDS GBR Göteborg, SWE 7 Aug 95 Shot Put 23.12 Randy BARNES USA Los Angeles, USA 20 May 90 Discus Throw 74.08 Jürgen SCHULT GDR Neubrandenburg, GDR 6 Jun 86 Hammer Throw -

Revista Corricolari Es + Correr Digital + Tarjeta € *Tarjeta Con Acceso a Ventajas 36 /Año Revista Papel + Tarjeta Vlrd N20,90 En *Valorado

CO-327-084.084 PUBLI MAPOMA.qxp:Maquetación 1 28/01/15 20:41 Página 84 CO-327-003.003 SUMARIO.qxp:Maquetación 1 29/01/15 17:15 Página 3 número 327 / febrero 2015 / www.corricolari.es CONTENIDOS EL ENIGMA AFRICANO: ¿POR QUÉ GANAN TODAS LAS COMPETICIONES? PÁG.14 Correr con sueños en la cabeza “Un atleta no puede correr con dinero en los APRENDE A BUSCAR LAS FRONTERAS DE TU CUERPO: bolsillos. Debe hacerlo con fe en su corazón y SOBREENTRENAMIENTO sueños en su cabeza”. Esta bonita cita pertenece a PÁG. 34 Emil Zatopek, atleta checoslovaco que alcanzó la • Homenaje a Emilio Ponce / PAG. 4 cima del fondo mundial a finales de los años pone en juego cuarenta y principios de los cincuenta. El mensaje •Londres que quiere transmitir es sencillo: hay que correr el récord del mundo de maratón / PAG. 6 para vivir, realizar un camino en búsqueda de la • Julio Albornos, el hombre de las medias maratones / PAG. 10 felicidad, que está muchas veces al final de nuestras • Diario de un maratoniano. Entrenando a alto nivel / PAG. 12 zancadas. Hay muchos atletas que, como predica • El enigma africano: ¿por qué lo ganan todo? / Zatopek, corren con sueños en su cabeza. PAG. 14 Completar un maratón, llegar a la meta de una • Entrenamiento en cuestas: carrera con tus hijos de la mano, acabar tu primera así debe ser la distancia e inclinación / PAG. 18 prueba de diez kilómetros o apuntarte a una carrera •Clavescotidianas para adelgazar: de montaña son desafíos con los que muchas no basta solo con correr / PAG. -

Canberra Runners

Canberra Runner OFFICIAL NEWSLETTER OF THE PRINT POST APPROVED ACT CROSS COUNTRY CLUB INC. PUBLICATION NO NUMBER 194 DEC 2009 PP 299436/00081 ISSN 1324 – 7557 CANBERRA RUNNER No. 194 December 2009 Official magazine of the ACT Cross Country Club Inc. (ACTCCC) The views in this magazine are not necessarily those of the ACTCCC. Address for all correspondence: GPO Box 252, Canberra ACT 2601 Founded: Jack Pennington OAM 1962 GENERAL INFORMATION: An information sheet and membership forms are available from the Secretary at the above address, and at club races, special events and the Women's and Girls' Jogalong. The information sheet provides full details of the club's objectives and activities. MEMBERSHIP: Membership of the club is open to anyone, with the membership year running from 1 January to 31 December.The membership fees are shown on the current membership form. Membership entitles runners to free entry at club season races, discounted entry to Club major events including the Jogalong, free “Canberra Runner” Magazine (mailed to all members). Contact Pam Faulks 62588679 CLUB RACES: The club conducts over 90 club races during the year ranging from 1k to 16k. The focal point of the year is the 'winter' season from April to September with races most weekends. A mid-week summer series is organised as a winter lead-in with eight races during February and March. In November a spring series of five races is conducted. Races are open to all runners. Non-members are charged an entry fee ($5 seniors, $2 under 20). A program of club events is available from the website. -

Cardiff 2016 F&F.Qxp WHM F&F

IAAF/Cardiff University WORLD HALF MARATHON CHAMPIONSHIPS FACTS & FIGURES Incorporating the IAAF World Half Marathon Championships (1992-2005/2008-2010-2012-2014) IAAF World Road Running Championships 2006/2007 Past Championships...............................................................................................1 Past Medallists .......................................................................................................1 Overall Placing Table..............................................................................................5 Most Medals Won...................................................................................................6 Youngest & Oldest..................................................................................................7 Most Appearances by athlete.................................................................................7 Most Appearances by country................................................................................8 Country Index .......................................................................................................10 World Road Race Records & Best Performances at 15Km, 20Km & Half Mar .........39 Progression of World Record & Best Performance at 15Km, 20Km & Half Mar .......41 CARDIFF 2016 ★ FACTS & FIGURES/PAST CHAMPS & MEDALLISTS 1 PAST CHAMPIONSHIPS –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– These totals do not include athletes entered for the championships who never started, but teams are counted -

RESULTS Half Marathon Women

/Cardiff University Cardiff (GBR) World Half Marathon Championships 26 March 2016 RESULTS Half Marathon Women RECORDS RESULT NAME COUNTRY AGE VENUE DATE World Record Women Only WRwo 1:06:25 Lornah KIPLAGAT NED 33 Udine 14 Oct 2007 Championships Record CR 1:06:25 Lornah KIPLAGAT NED 33 Udine 14 Oct 2007 World Leading WL 1:06:04 Cynthia Jerotich LIMO KEN 27 Ras Al Khaimah 12 Feb 2016 26 March 2016 13:35 START TIME 12° C 87 % TEMPERATURE HUMIDITY 15:27 END TIME 12° C 87 % PLACE BIB NAME COUNTRY DATE of BIRTH RESULT TIME BEHIND 1 156 Peres JECHIRCHIR KEN 27 Sep 93 1:07:31 2 159 Cynthia Jerotich LIMO KEN 18 Dec 89 1:07:34 + 3 3 160 Mary Wacera NGUGI KEN 17 Dec 88 1:07:54 + 23 4 129 Netsanet GUDETA ETH 12 Feb 91 1:08:01 SB + 30 5 130 Genet YALEW ETH 31 Dec 92 1:08:15 + 44 6 158 Gladys Chesir KIPTAGELAI KEN 20 Feb 93 1:08:46 + 1:15 7 157 Pascalia Chepkorir KIPKOECH KEN 22 Dec 88 1:09:44 SB + 2:13 8 126 Dehininet DEMSEW ETH 15 Sep 84 1:10:13 PB + 2:42 9 171 Gladys TEJEDA PER 30 Sep 85 1:10:14 AR + 2:43 10 151 Yuka ANDO JPN 16 Mar 94 1:10:34 + 3:03 11 184 Janet CHEROBON-BAWCOM USA 22 Aug 78 1:10:46 SB + 3:15 12 105 Eloise WELLINGS AUS 09 Nov 82 1:10:47 + 3:16 13 103 Milly CLARK AUS 01 Mar 89 1:10:48 PB + 3:17 14 154 Miho SHIMIZU JPN 13 May 90 1:10:51 + 3:20 15 185 Sara HALL USA 15 Apr 83 1:10:58 + 3:27 16 148 Veronica INGLESE ITA 22 Nov 90 1:10:59 SB + 3:28 17 153 Mizuki MATSUDA JPN 31 May 95 1:11:00 + 3:29 18 104 Cassie FIEN AUS 15 Sep 85 1:11:13 PB + 3:42 19 114 Kellys ARIAS COL 03 Jun 89 1:11:21 PB + 3:50 20 109 Lanni MARCHANT CAN 11 Apr 84