Viva LA Musica! Choir • ORCHESTRA Shulamit Hoffmann

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Race of Sound: Listening, Timbre, and Vocality in African American Music

UCLA Recent Work Title The Race of Sound: Listening, Timbre, and Vocality in African American Music Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9sn4k8dr ISBN 9780822372646 Author Eidsheim, Nina Sun Publication Date 2018-01-11 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Race of Sound Refiguring American Music A series edited by Ronald Radano, Josh Kun, and Nina Sun Eidsheim Charles McGovern, contributing editor The Race of Sound Listening, Timbre, and Vocality in African American Music Nina Sun Eidsheim Duke University Press Durham and London 2019 © 2019 Nina Sun Eidsheim All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper ∞ Designed by Courtney Leigh Baker and typeset in Garamond Premier Pro by Copperline Book Services Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Title: The race of sound : listening, timbre, and vocality in African American music / Nina Sun Eidsheim. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2018. | Series: Refiguring American music | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers:lccn 2018022952 (print) | lccn 2018035119 (ebook) | isbn 9780822372646 (ebook) | isbn 9780822368564 (hardcover : alk. paper) | isbn 9780822368687 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: lcsh: African Americans—Music—Social aspects. | Music and race—United States. | Voice culture—Social aspects— United States. | Tone color (Music)—Social aspects—United States. | Music—Social aspects—United States. | Singing—Social aspects— United States. | Anderson, Marian, 1897–1993. | Holiday, Billie, 1915–1959. | Scott, Jimmy, 1925–2014. | Vocaloid (Computer file) Classification:lcc ml3917.u6 (ebook) | lcc ml3917.u6 e35 2018 (print) | ddc 781.2/308996073—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018022952 Cover art: Nick Cave, Soundsuit, 2017. -

Woodwind Grades Syllabus

Woodwind Syllabus Flute, Clarinet, Oboe, Bassoon, Saxophone & Recorder Graded exams 2017–2022 Important information Changes from the previous syllabus Repertoire lists for all instruments have been updated. Initial exams are now offered for flute and clarinet. New series of graded flute and clarinet books are available, containing selected repertoire for Initial to Grade 8. Technical work for oboe, bassoon and recorder has been revised, with changes to scales and arpeggios and new exercises for Grades 1–5. New technical work books are available. Own composition requirements have been revised. Aural test parameters have been revised, and new specimen tests publications are available. Improvisation test requirements have changed, and new preparation materials are available on our website. Impression information Candidates should refer to trinitycollege.com/woodwind to ensure that they are using the latest impression of the syllabus. Digital assessment: Digital Grades and Diplomas To provide even more choice and flexibility in how Trinity’s regulated qualifications can be achieved, digital assessment is available for all our classical, jazz and Rock & Pop graded exams, as well as for ATCL and LTCL music performance diplomas. This enables candidates to record their exam at a place and time of their choice and then submit the video recording via our online platform to be assessed by our expert examiners. The exams have the same academic rigour as our face-to-face exams, and candidates gain full recognition for their achievements, with -

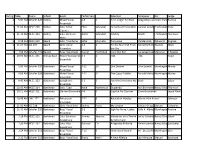

Rating Time Room School Event Performers Selection Composer

Rating Time Room School Event Performers Selection Composer Acc Judge 1 9:09>AM Schafer>320 Ashley Mixed>Vocal> 4G6 4 Ain't>Judgin'>No>Man Greg>Gilpin>and>John>ParkerRockne Ensemble 1 11:06>AM NECE>239 Ashley Solo:>B>Flat> Ellen Schnabel Lamento>et>Tarantelle Gabriel>GrovlezP.Schnabel Riley Clarinet 1 11:33>AM NECE>304 Ashley Solo:>Baritone> Addie Schnabel Fidelity Smith E.Schnabel Thomson Horn 1 9:18>AM NECE>319 Beach Solo:>Trombone Sofia Muruato Turquoise Vandercook WilWand Bugbee 1 11:15>AM JSC>207 Beach Girls'>Vocal> 2G3 2 Till>the>Stars>Fall>From> Albrecht/AlthouseTescher Wald Ensemble the>Sky 1 1:54>PM Schafer>219 Beulah Boys'>Vocal>Solo Daniel> Harildstad Caro>Mio>Ben Giuseppe>GiordaniMeissner K.Bowles 1 10:03>AM NECE>335 Bishop>Ryan Mixed>WoodWind> 2G3 2 TBA TBA Boyd Ensemble * 9:00>AM Schafer>309 Bottineau Mixed>Vocal> 7G12 10 Ose>Shalom John>Leavitt Blumhagen Morey Ensemble * 9:09>AM Schafer>309 Bottineau Mixed>Vocal> 7G12 12 The>Gypsy>Fiddler Ronald>MelroseBlumhagen Morey Ensemble 1 9:45>AM NECE>323 Bottineau Saxophone> 2G3 2 TWo>Part>Invention>No.> Bach Salzer Ensemble 8 1 10:03>AM NECE>304 Bottineau Solo:>Tuba Halie Haakenson Stupendo N.K.BrahmstedtNancy>Olson>BThomson 1 10:21>AM NECE>321 Bottineau Clarinet>Ensemble 4G6 6 Caprice>For>Clarinet Clare>Grundman Joyce>Alme 1 10:48>AM LMC>177 Bottineau Percussion> 7G12 8 Balalaikan>Holiday Morris>Alan>Brand Johnson Ensemble 1 11:06>AM JSC>318 Bottineau Girls'>Vocal>Solo Shelby Pedie My>Johann Edvard>Grieg Marum D.Bowles 1 11:42>AM Schafer>320 Bottineau Boys'>Vocal> 2G3 2 Sigh>No>More,>Ladies -

Drum & Percussion

76164 10 Classical_PercMixEns: 6/18/09 4:20 PM Page 450 450HAL LEONARD DRUM & PERCUSSION 451 Snare Drum 451 Mallet Instruments (Marimba, Xylophone, Vibraphone) 453 Timpani 453 Percussion Music for One Player 454 Percussion Ensembles 457 Percussion with Various Instruments 459 Instruction and Supplementary Materials 2009-2010 CLASSICAL MUSIC CATALOG 76164 10 Classical_PercMixEns: 6/18/09 4:20 PM Page 451 DRUM & PERCUSSION 451 SNARE DRUM MALLET BUGGERT INSTRUMENTS ______04479337 Bobbin’ Back (Grade IV) Rubank RUBX313.........................................................$4.95 With Piano unless otherwise noted. ______04479340 Echoing Sticks (Grade IV) Rubank RUBX315.........................................................$4.95 ABE, KEIKO ______04479345 Rolling Accents (Grade IV) ______49042571 Marimba d’amore Rubank RUBX391.........................................................$4.95 Schott Japan SJ00051.................................................$18.00 ______04479346 Thundering Through (Grade V) ______49042570 Works for Marimba Rubank RUBX317.........................................................$4.95 Schott Japan SJ00050.................................................$29.95 GAUTHREAUX, GUY ______49013538 Works for Marimba Duo _______00317056 American Suite for Unaccompanied Snare Drum Performance Score Schott Japan SJ052.....................$16.95 Meredith Music ...........................................................$12.95 BACH, JOHANN SEBASTIAN GINER, BRUNO ______00347792 Concerto in A minor (Goldenberg) ______50561309 Etudes -

Sir Karl Jenkins Returns to the NCPA to Lead the Symphony Orchestra Of

INTERNATIONAL Sir Karl Jenkins Music That Moves But, says Jenkins, breaking barriers Sir Karl Jenkins returns to the NCPA to or being novel for the sake of it isn’t lead the Symphony Orchestra of India at necessarily an ideal that he chases. “I don’t aim to please people. Even if the Indian premiere of his exciting new I did, I could never guess what they composition, The Universe. The celebrated like. I’m true to myself and the style that I write, and it does happen to Welsh composer and conductor talks to communicate with people – which Beverly Pereira about his genre-defying is my greatest aim, really.” classical music A human connect It is understandable why his shows are always packed houses. In 1999, or a composer formally interpolation of musical elements. Jenkins, who holds a doctorate trained in Western Requiem (2005) integrates in music from the University of classical music, Sir Karl Japanese death poems with Wales, was commissioned to Jenkins isn’t one to shy the movements of the Catholic write The Armed Man – A Mass for away from embracing Requiem, or mass for the souls Peace, an anti-war composition other musical genres. of the dead, and is performed by that premiered in the year 2000. FWhile classical music does form a choir and an orchestra with a It includes excerpts from the the basis of his compositions, his Japanese bamboo flute called Mahabharata, the Bible and the work straddles the far-removed the shakuhachi thrown into the Islamic call to prayer, interspersed worlds of folk, jazz and world unlikely mix. -

New Music for Orchestra

Michel van der Aa (*1970) Johannes Boris Borowski (*1979) Reversal (2016) 11’ Stretta (2016–17) 23’ Releases 2016–18 for orchestra for piano and orchestra WP: 13 Jan 2017 Staatsoper, Hamburg WP: 15 Nov 2017 Philharmonie, Berlin Andrey Kaydanowskiy, choreographer / Daniel Barenboim, piano / Staatskapelle Berlin / Bundesjugendballett / Bundesjugendorchester / Zubin Mehta Alexander Shelley for piano and orchestra 1.1.2(II=bcl).2(II=dbn)—4.2.2.btrbn.0—perc(2):vib/glsp/ 2.2.2.2.dbn—4.2.2.1—timp.perc(3):marimba/vib/glsp/t.bells/ marimba/BD/SD/maracas/bongo/tgl/bamboo chimes/glass SD/BD/4tom-t/2bongo/2Conga/tamb/2lion’s roar/2splash cym/ chimes/BD/log dr/cyms/whip/church bell or t.bells—harp— 2crash cym/2ride cym/3Chin.cym/tam-t/5opera gong/rainmaker/ strings(16.14.12.10.8) whip(lg)/2ratchet/wind machine/mark tree/wood chimes—harp— strings(10.8.6.6.3; alternatively 6db) John Adams (*1947) Walter Braunfels (1882–1954) Lola Montez Tag- und Nachtstücke (1933–34) 30’ Does the Spider Dance (2016) 4’ for piano and orchestra from ‘Girls of the Golden West’ WP: 13 Jul 2017 Ruhrfestspielhaus, Recklinghausen for orchestra Michael Korstick, piano / Neue Philharmonie WP: 06 Aug 2016 Civic Auditorium, Santa Cruz, CA Westfalen / Peter Ruzicka Cabrillo Festival of Contemporary Music / Marin Alsop 2(I,II=picc).2.2.2(II=dbn)—4.2.2.1—timp.perc(1):tamb/tgl/xyl/SD/ 3(III=picc).2.corA.2.bcl.2.dbn—4.3.3.0—perc(1):BD—pft—strings glsp/cyms—harp—strings (*1939) Louis Andriessen Enrico Chapela (*1974) Agamemnon (2017) 20’ Antikythera (2016) 10’ RCHESTRA for orchestra -

Musical Memories

~ ---- APPENDIX 1 MUSICAL MEMORIES Heneghan, Frank O'Grady, Dr Geraldine Andrews, Edward O'Reilly, Dr James]. Beckett, Dr Walter Keogh, Val O'Rourke, Miceal Bonnie,Joe King, Superintendent John Calthorpe, Nancy Larchet, Dr John F Roche, Kevin Darley, Arthur Warren Maguire, Leo Ronayne, john Davin, Maud McCann, Alderman John Rowsome, Leo Donnelly, Madame Lucy McNamara. Michael Sauerzweig, Colonel F C. Dunne, Dr Veronica Mooney, Brighid Sherlock, Dr Lorean G. Gannon, Sister Mary O'Brien, Joseph Valentine, Hubert O'Callaghan, Colonel Frederick Gillen, Professor Gerard Walton, Martin A. Greig, William Sydney O'Conor, Dr John 85 86 Edward Andrews were all part-time, and so could get holiday pay by getting the dole. Many summer days I spent in a Edward Andrews was porter, and his wife, queue at the Labour Exchange. Mary Andrews, was housekeeper, in the The large room at the head of the main stairs Assembly House, South William Street, from was the Library, just three or four cases of books about 1885. He was the first porter connected and music, looked after by Willie Reidy, who also with the Municipal School of Music. They were taught the cello in this room. The Principal at this employed by Dublin Corporation, and remained time was Joseph O'Brien. in South William Street when the Municipal Soon a terrible thought struck me. The way I School of Music moved premises. They had a was living meant that I should go through this life daughter, Mary, who was one of the first piano without ever playing in a string quartet. This was students, and her two daughters, Eithne Russell intolerable, so before long I left a free half-hour in and the late Maura Russell, were both students my timetable and went to Willie Reidy to learn the and teachers in the College of Music. -

New Music for Orchestra

Tapdance (2013) 15’ Michel van der Aa (*1970) Concerto for percussion and large ensemble WP: 24 May 2014 Concertgebouw, Amsterdam Releases 2012–14 Hysteresis (2013) 17’ Colin Currie / Asko|Schönberg / Reinbert de Leeuw for solo clarinet, ensemble and soundtrack Solo percussion: tap table/marimba/tympanum; WP: 30 Apr 2014 Queen Elizabeth Hall, London 2.2.ssax(=tsax).asax.0.bcl.dbcl.0—2.2.2.0—perc:vib/t.bells/ Mark van de Wiel / London Sinfonietta / gongs/cyms/bongos/guiro/slit dr/BD/drum kit—harp—pft— bgtr—strings(min:3.3.2.2.1, max:5.4.3.3.2) Baldur Brönnimann bn—tpt—perc(1)—soundtrack(laptop,1player)—strings(1.0.1.1.1 [all amplified] or 4.0.3.2.1 or 6.0.5.4.2; db with low C strings) Oscar Bettison (*1975) Violin Concerto (2014) 25’ for violin and orchestra Livre des Sauvages (2012) 30’ WP: 06 Nov 2014 Concertgebouw, Amsterdam for large ensemble Janine Jansen / Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra / WP: 10 Apr 2012 Walt Disney Concert Hall, Vladimir Jurowski Los Angeles, CA Los Angeles Philharmonic New Music Group / Jeffrey Milarsky John Adams (*1947) 1(=picc,bfl).1(=soprano rec if available).2(I=Ebcl,II=bcl,dbcl).0— 1.1(=picc.tpt).1.0—perc:spring reco-reco(lg)/cast(mounted)/ desk-bells(from C to C)/susp.metal springs(med,lg)/whip/ The Gospel According to guiro(sm)/kick dr(prepared)/ratchets(sm,lg)/2ranch tgl/ 3ceramic mugs/t.bell(Ab)/wrenchophone/sandpaper bl/ the Other Mary (2012) 120’ 5gongs(G3,Bb3,B3,D4,F4)/Chin.clash cym/conch shell/ A Passion oratorio for orchestra, chorus and soloists almglocken(F#3 to C#5)/orchestral hammer/2tuning forks -

P E N in S U L a W O M E N 'S C H O R U S Saturday, May 15

1 2 0 2 WE HAVE A G N I R VOICE! P S Virtual Concert | Saturday, May 15, 2021 S 4pm PDT | 7pm EDT U R O H C S ' N E M O W A L U S N I N E P FROM THE INTERIM ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Welcome, and thank you for joining us this afternoon. As the Interim Artistic Director of the Peninsula Women's Chorus this spring, I'm thrilled to share the Chorus' artistry and hard work during this virtual time with you! This season, the PWC took on the task of responding to the past year's moments of hardship and joy through the way we best know how: our voices. We Have A Voice is comprised of six diverse American works that speak directly to our current moment in history. We reflect on darkness and isolation with Randall Thompson's "Come In," and we join the national conversation around justice and equity, facing fear, and speaking out with Moira Smiley's percussive "I Have A Voice." We were so grateful to be able to work virtually with Moira, as she helped us adapt the body percussion and movement for virtual choir, and more importantly, reminded us that although we've been virtual for the past seasons, we do have a voice. We also take time to reflect on themes of community, connection and hope through Caroline Shaw's "Dolce Cantavi," the stirring call for solidarity by west-coast based duo Mamuse, "We Shall Be Known," and the gospel anthem "The Storm Is Passing Over." Through Sarah Quartel's stunning "God will give orders" (in collaboration with fabulous cellist Emil Miland), we speak to the need we have felt for family, and the importance of looking to future generations to lead our way. -

To Search This List, Hit CTRL+F to "Find" Any Song Or Artist Song Artist

To Search this list, hit CTRL+F to "Find" any song or artist Song Artist Length Peaches & Cream 112 3:13 U Already Know 112 3:18 All Mixed Up 311 3:00 Amber 311 3:27 Come Original 311 3:43 Love Song 311 3:29 Work 1,2,3 3:39 Dinosaurs 16bit 5:00 No Lie Featuring Drake 2 Chainz 3:58 2 Live Blues 2 Live Crew 5:15 Bad A.. B...h 2 Live Crew 4:04 Break It on Down 2 Live Crew 4:00 C'mon Babe 2 Live Crew 4:44 Coolin' 2 Live Crew 5:03 D.K. Almighty 2 Live Crew 4:53 Dirty Nursery Rhymes 2 Live Crew 3:08 Fraternity Record 2 Live Crew 4:47 Get Loose Now 2 Live Crew 4:36 Hoochie Mama 2 Live Crew 3:01 If You Believe in Having Sex 2 Live Crew 3:52 Me So Horny 2 Live Crew 4:36 Mega Mixx III 2 Live Crew 5:45 My Seven Bizzos 2 Live Crew 4:19 Put Her in the Buck 2 Live Crew 3:57 Reggae Joint 2 Live Crew 4:14 The F--k Shop 2 Live Crew 3:25 Tootsie Roll 2 Live Crew 4:16 Get Ready For This 2 Unlimited 3:43 Smooth Criminal 2CELLOS (Sulic & Hauser) 4:06 Baby Don't Cry 2Pac 4:22 California Love 2Pac 4:01 Changes 2Pac 4:29 Dear Mama 2Pac 4:40 I Ain't Mad At Cha 2Pac 4:54 Life Goes On 2Pac 5:03 Thug Passion 2Pac 5:08 Troublesome '96 2Pac 4:37 Until The End Of Time 2Pac 4:27 To Search this list, hit CTRL+F to "Find" any song or artist Ghetto Gospel 2Pac Feat. -

The Armed Man (A Mass for Peace) – Karl Jenkins (Wales, 1944)

The Armed Man (A Mass for Peace) – Karl Jenkins (Wales, 1944) Uitvoerenden: Fanfare Orpheus Bathmen o.l.v. Berjan Morsink. Projectkoor HetKoor o.l.v. dirigent Mark Schrijver. Lucie Tromp - alt-soliste Karl Jenkins heeft na zijn opleiding in de klassieke muziek, o.a. aan The Royal Academy of Music in Londen, een veelzijdige ontwikkeling als componist en musicus doorgemaakt. In de jaren zestig kreeg hij grote bekendheid als jazz- en rockmuzikant. Als toetsenist speelde hij mee in de experimentele rockband The Soft Machine, waarvan hij later ook de leider werd. Pas in 1995 brak hij als klassiek componist door met het album Adiemus. The Armed Man, dat de ondertitel Mis voor de vrede heeft, is geschreven in opdracht van het Royal Armouries Museum ter gelegenheid van de verhuizing van dit museum van Londen naar Leeds. De opening van de nieuwe locatie en de aanstaande millenniumwisseling vormden voor Guy Wilson, toen directeur van het museum, de aanleiding Jenkins te vragen om deze compositie te maken. Hieruit spreekt hoop op een millenium zonder oorlog. De première, o.l.v. Jenkins zelf, vond plaats in de Royal Albert Hall in Londen (2000). De oorspronkelijke versie is geschreven voor symfonieorkest. Jenkins heeft The Armed Man opgedragen aan de slachtoffers van de Kosovocrisis, die door de luchtaanvallen van de NAVO in maart 1999 tot een hoogtepunt kwam. Zonder een pacifistische moraal of specifieke geloofsovertuiging te verkondigen kan de vraag worden gesteld waarom er, ondanks de vele lessen uit het verleden, nog steeds naar de wapenen wordt gegrepen. Jenkins en Wilson kozen teksten uit, die Hindoestaanse, Islamitische, Joodse en Christelijke tradities verbinden. -

A Randomized Study of Different Musical Genres in Supporting

Set and Setting: A Randomized Study of Different Musical Genres in Supporting Psychedelic Therapy Justin C. Strickland1, Albert Garcia-Romeu1, and Matthew W. Johnson1* 1 Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, 5510 Nathan Shock Drive, Baltimore, MD 21224, USA *Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Matthew W. Johnson, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, 5510 Nathan Shock Drive, Baltimore, MD 21224-6823, USA. Email: [email protected] This manuscript was accepted for publication on December 11, 2020 by ACS Pharmacology & Translational Science. This is not the copy of record. 1 Abstract Mounting evidence supports the serotonin 2A receptor agonist psilocybin as a psychiatric pharmacotherapy. Little research has experimentally examined how session “set and setting” impacts subjective and therapeutic effects. We analyzed effects of musical genre played during sessions of a psilocybin study for tobacco smoking cessation. Participants (N=10) received psilocybin (20-30mg/70kg) in two sessions, each with a different genre (Western classical versus overtone-based), with order counterbalanced. Participants chose one genre for a third session (30mg/70kg). Mystical experiences scores tended to be higher in overtone-based than Western classical sessions. Six of ten participants chose overtone-based music for a third session. Biologically-confirmed smoking abstinence was similar based on musical choice, with a slight benefit for participants choosing the overtone-based playlist (66.7% versus 50%). These data call into question whether Western classical music typically used in psychedelic therapy holds unique benefit. Broadly, they call for experimentally examining session components toward optimizing psychedelic therapeutic protocols.