Download Article [PDF]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intergovernmental Relations Policy Framework

INTERGOVERNMENTAL AND INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS 1 POLICY : INTERGOVERNMENTAL RELATIONS POLICY FRAMEWORK Item CL 285/2002 PROPOSED INTERGOVERNMENTAL RELATIONS POLICY FRAMEWORK MC 05.12.2002 RESOLVED: 1. That the report of the Strategic Executive Director: City Development Services regarding a proposed framework to ensure sound intergovernmental relations between the EMM, National and Provincial Government, neighbouring municipalities, the S A Cities Network, organised local government and bulk service providers, BE NOTED AND ACCEPTED. 2. That all Departments/Portfolios of the EMM USE the Intergovernmental Relations Policy Framework to develop and implement mechanisms, processes and procedures to ensure sound intergovernmental relations and TO SUBMIT a policy and programme in this regard to the Speaker for purposes of co-ordination and approval by the Mayoral Committee. 3. That the Director: Communications and Marketing DEVELOP a policy on how to deal with intergovernmental delegations visiting the Metro, with specific reference to intergovernmental relations and to submit same to the Mayoral Committee for consideration. 4. That intergovernmental relations BE INCORPORATED as a key activity in the lOP Business Plans of all Departments of the EMM. 5. That the Ekurhuleni Intergovernmental Multipurpose Centre Steering Committee INCORPORATE the principles contained in the Intergovernmental Relations Framework as part of the policy on multipurpose centres to be formulated as contemplated in Mayoral Committee Resolution (Item LED 21-2002) of 3 October 2002. 6. That the City Manager, in consultation with the Strategic Executive Director: City Development Services, FINALISE AND APPROVE the officials to represent the EMM at the Technical Working Groups of the S A Cities Network. 7. That the Strategic Executive Director: City Development SUBMIT a further report to the Mayoral Committee regarding the necessity of participation of the Ekurhuleni Metropolitan Municipality and its Portfolios/Departments on public bodies, institutions and organisations. -

The Anti-Apartheid Movements in Australia and Aotearoa/New Zealand

The anti-apartheid movements in Australia and Aotearoa/New Zealand By Peter Limb Introduction The history of the anti-apartheid movement(s) (AAM) in Aotearoa/New Zealand and Australia is one of multi-faceted solidarity action with strong international, but also regional and historical dimensions that gave it specific features, most notably the role of sports sanctions and the relationship of indigenous peoples’ struggles to the AAM. Most writings on the movement in Australia are in the form of memoirs, though Christine Jennett in 1989 produced an analysis of it as a social movement. New Zealand too has insightful memoirs and fine studies of the divisive 1981 rugby tour. The movement’s internal history is less known. This chapter is the first history of the movement in both countries. It explains the movement’s nature, details its history, and discusses its significance and lessons.1 The movement was a complex mosaic of bodies of diverse forms: there was never a singular, centralised organisation. Components included specific anti-apartheid groups, some of them loose coalitions, others tightly focused, and broader supportive organisations such as unions, churches and NGOs. If activists came largely from left- wing, union, student, church and South African communities, supporters came from a broader social range. The liberation movement was connected organically not only through politics, but also via the presence of South Africans, prominent in Australia, if rather less so in New Zealand. The political configuration of each country influenced choice of alliance and depth of interrelationships. Forms of struggle varied over time and place. There were internal contradictions and divisive issues, and questions around tactics, armed struggle and sanctions, and how to relate to internal racism. -

South African Crime Quarterly, No 48

CQ Cover June 2014 7/10/14 3:27 PM Page 1 Reviewing 20 years of criminal justice in South Africa South A f r i c a n CRIME QUA RT E R LY No. 48 | June 2014 Previous issues Stacy Moreland analyses judgements in rape ISS Pretoria cases in the We s t e r n Cape, finding that Block C, Brooklyn Court p a t r i a rchal notions of gender still inform 361 Veale Street judgements in rape case. Heidi Barnes writes a New Muckleneuk case note on the Constitutional Court case Pretoria, South Africa F v Minister of Safety and Security. Alexander Tel: +27 12 346 9500 Hiropoulos and Jeremy Porter demonstrate how Fax:+27 12 460 0998 Geographic Information Systems can be used, [email protected] along with crime pattern theory, to analyse police crime data. Geoff Harris, Crispin Hemson ISS Addis Ababa & Sylvia Kaye report on a conference held in 5th Floor, Get House Building Durban in mid-2013 about measures to reduce Africa Avenue violence in schools; and Hema Harg o v a n Addis Ababa, Ethiopia reviews the latetest edition of Victimology in Tel: +251 11 515 6320 South Africa by Robert Peacock (ed). Fax: +251 11 515 6449 [email protected] Andrew Faull responds to Herrick and Charman ISS Dakar (SACQ 45), delving into the daily liquor policing 4th Floor, Immeuble Atryum in the Western Cape. He looks beyond policing Route de Ouakam for solutions to alcohol-related harms. Claudia Forester-Towne considers how race and gender Dakar, Senegal influence police reservists' views about their Tel: +221 33 860 3304/42 work. -

Apartheid South Africa Xolela Mangcu 105 5 the State of Local Government: Third-Generation Issues Doreen Atkinson 118

ress.ac.za ress.ac.za p State of the Nation South Africa 2003–2004 Free download from www.hsrc Edited by John Daniel, Adam Habib & Roger Southall ress.ac.za ress.ac.za p Free download from www.hsrc ress.ac.za ress.ac.za p Compiled by the Democracy & Governance Research Programme, Human Sciences Research Council Published by HSRC Press Private Bag X9182, Cape Town, 8000, South Africa HSRC Press is an imprint of the Human Sciences Research Council Free download from www.hsrc ©2003 Human Sciences Research Council First published 2003 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. ISBN 0 7969 2024 9 Cover photograph by Yassir Booley Production by comPress Printed by Creda Communications Distributed in South Africa by Blue Weaver Marketing and Distribution, PO Box 30370, Tokai, Cape Town, South Africa, 7966. Tel/Fax: (021) 701-7302, email: [email protected]. Contents List of tables v List of figures vii ress.ac.za ress.ac.za p Acronyms ix Preface xiii Glenn Moss Introduction Adam Habib, John Daniel and Roger Southall 1 PART I: POLITICS 1 The state of the state: Contestation and race re-assertion in a neoliberal terrain Gerhard Maré 25 2 The state of party politics: Struggles within the Tripartite Alliance and the decline of opposition Free download from www.hsrc Roger Southall 53 3 An imperfect past: -

November 2009.Pdf

Project of the Community Law Centre CSPRI "30 Days/Dae/Izinsuku" CSPRI "30 Days/Dae/Izinsuku" November 2009 November 2009 In this Issue: CORRUPTION AND GOVERNANCE SENTENCING AND PAROLE SAFETY AND SECURITY HEALTH OTHER AFRICAN COUNTRIES Top of Page CORRUPTION AND GOVERNANCE Prison officers suspended: A report in News24 said that the Western Cape Correctional Services security chief, Lionel Adams and another senior official have been suspended after an unauthorised release of a prisoner. The Department's spokesperson, Ofentse Morwane, confirmed that Adams and Julius Mentoor of the Cape Town Community Corrections office were suspended on full pay following the release of a prisoner from the Goodwood correctional centre. SAPA, 11 November 2009, News24, at http://www.news24.com/Content/SouthAfrica/News/1059/0df6455b566b488c8d0b2b8abd6fae34/11-11- 2009-07-02/Cape_prison_bosses_suspended Lack of accountability at Correctional Services: The Minister of Correctional Services, Nosiviwe Mapisa-Nqakula, lamented the lack of accountability and non-compliance that is deeply engrained in her ministry. While briefing Parliament's Portfolio Committee on Correctional Services, the Minister said "The truth of the matter is that the organisational culture in the Department of Correctional Services, is (that) of non-accountability", adding that "The lines of accountability in [her] view are very blurred." News24 Reported. SAPA, 17 November 2009, New24 at http://www.news24.com/Content/SouthAfrica/News/1059/3fcf01e25e3d4dcea46ff23422a9ca2f/11-11- 2009-05-03/Prisons_not_accountable MPs get report on prison fraud: A report from IOL stated that the Special Investigations Unit (SIU) has briefed Members of Paliament(MPs) on an alleged prison graft at the Department of Correctional Services. -

Table of Contents

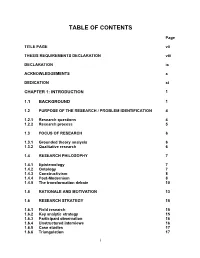

TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TITLE PAGE vii THESIS REQUIREMENTS DECLARATION viii DECLARATION ix ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS x DEDICATION xi CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 BACKGROUND 1 1.2 PURPOSE OF THE RESEARCH / PROBLEM IDENTIFICATION 4 1.2.1 Research questions 4 1.2.2 Research process 5 1.3 FOCUS OF RESEARCH 6 1.3.1 Grounded theory analysis 6 1.3.2 Qualitative research 6 1.4 RESEARCH PHILOSOPHY 7 1.4.1 Epistemology 7 1.4.2 Ontology 7 1.4.3 Constructivism 8 1.4.4 Post-Modernism 8 1.4.5 The transformation debate 10 1.5 RATIONALE AND MOTIVATION 13 1.6 RESEARCH STRATEGY 15 1.6.1 Field research 15 1.6.2 Key analytic strategy 15 1.6.3 Participant observation 16 1.6.4 Unstructured interviews 16 1.6.5 Case studies 17 1.6.6 Triangulation 17 i 1.6.7 Purposive sampling 17 1.6.8 Data gathering and data analysis 18 1.6.9 Value of the research and potential outcomes 18 1.6.10 The researcher's background 19 1.6.11 Chapter layout 19 CHAPTER 2: CREATING CONTEXT: SPORT AND DEMOCRACY 21 2.1 INTRODUCTION 21 2.2 SPORT 21 2.2.1 Conceptual clarification 21 2.2.2 Background and historical perspective 26 2.2.2.1 Sport in ancient Rome 28 2.2.2.2 Sport and the English monarchy 28 2.2.2.3 Sport as an instrument of politics 29 2.2.3 Different viewpoints 30 2.2.4 Politics 32 2.2.5 A critical overview of the relationship between sport and politics 33 2.2.5.1 Democracy 35 (a) Defining democracy 35 (b) The confusing nature of democracy 38 (c) Reflection on democracy 39 2.3 CONCLUSION 40 CHAPTER 3: SPORT IN A GLOBAL CONTEXT 42 3.1 INTRODUCTION 42 3.2 A GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE OF SPORT 43 -

Part I. Current Conditions and Problems

Part I. Chapter 1. General Remarks Part I. Current Conditions and Problems Chapter 1. General Remarks Hideo ODA(Keiai University) 1. South Africa in the 1990s as a Major Transi- 2. The Many Facets of South Africa as a Recip- tion Period ient of Japan’s Official Development Assis- tance The democratization domino effect that swept across Eastern Europe in the latter half of 1989 was highlighted South Africa is a regional superpower with a level of by the historic tearing down of the Berlin Wall in political, economic and social( and of course military) November to pave the way for German reunification, and development that far surpasses the normal level for was closely followed by the December US-Soviet lead- Africa, and when it is viewed in the context of a recipient ers’ summit between Presidents Bush and Gorbachev of Japan’s official development assistance, many differ- that confirmed the end of the Cold War. The 1990s was ing facets of the country stand out. the first decade of the “post-Cold War era”, the world’s First is that South Africa has a dual structure in one greatest historical transition period since the end of country: a rich developed society coexisting with a poor World War II. The effect of this was a far-reaching move- developing society. This is the largest legacy of the ment toward democracy( and a market economy) that Apartheid system, and correcting this imbalance should was felt in all parts of the world. be seen as a key element of Japan’s assistance for South Africa was no exception. -

Andre Odendaal

‘HERITAGE’ AND THE ARRIVAL OF POST-COLONIAL HISTORY IN SOUTH AFRICA BY PROF ANDRE ODENDAAL (Honorary Professor of History and Heritage Studies, University of the Western Cape). Please note: this paper is a work in progress. It is not to be quoted or cited without the permission of the author. Paper presented to the United States African Studies Association annual conference, Washington DC, 5-8 December 2002 ©2002, Andre Odendaal, all rights reserved 1 INTRODUCTION This paper was first presented as a keynote address to the South African Historical Association Annual Conference on “Heritage Creation a Research: The Restructuring of Historical Studies in Southern Africa” held at the Rand Afrikaans University in Johannesburg on 24-26 June 2002. Speaking to academic historians after a five years absence from a university campus, while heavily occupied in the building and management of a new historical institution, rather than concentrated research and reflection, I approached the address with some trepidation. At the same time I was confident that a new era had dawned in which the public history and heritage domain, which I had been involved in for 17 years, could claim a place alongside ‘academic’ history as an integral part of the broad field of critical South African historical studies. The Honorary Professorship awarded to me by the University of the Western Cape (UWC) in December 2001, carrying the title Professor of History and Heritage Studies, helped underline this point. From the time in the 1980s that new popular and public history approaches (re)emerged, many academic historians have been uncomfortable with, even disdainful towards what they have seen as politically biased and shallow engagements with and depictions of the past. -

University of Kwazulu-Natal Press Alegi, P

$%!"#'&($$# 758):)<1>-6)4A;1;7.=;16-;;"<:)<-/1-;.7: :7.-;;176)4:1+3-<)6,!=/*A16"7=<0.:1+);16+- *A ,=):,7=1;7-<B-- thesis>@-84??0/49;,=?4,71@7147809?:1?30=0<@4=0809?>1:=?30/02=00:1 Doctor of Philosophy (Leadership) =,/@,?0%.3::7:1@>490>> and Leadership College of Law and Management Studies "=8-:>1;7::7.#0-=6;-4;-: DECLARATION I, Eduard Louis Coetzee, declare that (i) The research reported in this dissertation / thesis, except where otherwise indicated, is my original research. (ii) This dissertation / thesis has not been submitted for any degree or examination at any other university. (iii) This dissertation / thesis does not contain any other person’s data, pictures, graphs or other information, unless specifically acknowledged as being sourced from other persons. (iv) This dissertation / thesis does not contain any other person’s writing, unless specifically acknowledged as being sourced from other researchers. Where other written sources have been quoted, then: a) their words have been re-written but the general information attributed to them has been referenced; b) where their exact words have been used, their writing has been placed inside quotation marks, and referenced. (v) Where I have reproduced a publication of which I am author, co-author or editor, I have indicated in details which part of the publication was actually written by myself alone and have fully referenced such publications. (vi) This dissertation / thesis does not contain any text, graphics or tables copied or pasted from the internet, unless specifically, acknowledged, and the source being detailed in the dissertation / thesis and in the References sections. -

Government Communication and Information

33 Pocket Guide to South Africa 2008/09 GOVERNMENT of the injustices of the country’s non-democratic past. of theinjusticescountry’s mined –that werecarriedoutwithanacuteawareness negotiations –difficultbutdeter- detailed andinclusive Constitutionwastheresultofremarkably Africa’s South Pocket Guide to South Africa 2008/09 GOVERNMENT The Constitution is the supreme law of the country. No other law or government action may supersede its provisions. The Preamble to the Constitution states that its aims are to: sHEALTHEDIVISIONSOFTHEPASTANDESTABLISHASOCIETYBASEDON democratic values, social justice and fundamental human rights sIMPROVETHEQUALITYOFLIFEOFALLCITIZENSANDFREETHEPOTENTIAL of each person sLAYTHEFOUNDATIONSFORADEMOCRATICANDOPENSOCIETYINWHICH GOVERNMENTISBASEDONTHEWILLOFTHEPEOPLEANDEVERYCITIZEN ISEQUALLYPROTECTEDBYLAW sBUILDAUNITEDANDDEMOCRATIC3OUTH!FRICAABLETOTAKEITSRIGHT- ful place as a sovereign state in the family of nations. Government Government consists of national, provincial and local spheres. The powers of the legislature, executive and courts are separate. Parliament Parliament consists of the National Assembly and the National Council of Provinces (NCOP). Parliamentary sittings are open to the public. Several measures have been implemented to make Parliament more accessible and accountable. The National Assembly consists of no fewer than 350 and no more than 400 members, elected through a system of proportional representa- tion for a five-year term. It elects the President and scrutinises the executive. National Council of Provinces The NCOP consists of 54 permanent members and 36 special delegates, and aims to represent provincial interests in the national sphere of government. The Presidency The President is the head of state and leads the Cabinet. He or she is elected by the National Assembly from among its members, and leads the country in the interest of national unity, in accord- ance with the Constitution and the law. -

From the Desk of Jennifer Davis

From the Desk of Jennifer Davis June 17, 1999 SA's new cabinet Ministers: 1. President: Thabo Mbeki 2. Deputy President: Jacob Zuma 3. Agriculture & Land Affairs: Thoko Didiza 4. Arts, Culture, Science & Technology: Ben Ngubane 5. Correctional Services: Ben Skosana 6. Defence: Patrick Lekota 7. Education: Kader Asmal 8. Environmental Affairs & Tourism: Valli Moosa 9. Finance: Trevor Manuel 10. Foreign Affairs: Nkosazana Dlarnini-Zuma 11. Health: Manto Tshabalala-Msimang 12. Horne Affairs: Mangosuthu Buthelezi 13. Housing: Sankie Mthernbi-Mahanyele 14. Justice & Constitutional Development: Penuel Maduna 15. Labour: Shepherd Md1adlana 16. Minerals & Energy Affairs: Phurnzile Mlarnbo-Ngcuka 17. Communications: Ivy Matsepe-Casaburri 18. Provincial and Local Government: Sydney Mufamadi 19. Public Enterprises: Jeff Radebe 20. Public Service & Administration: Geraldine Fraser-Moleketi 21. Public Works: Stella Sigcau 22. Safety & Security: Steve Tshwete 23. Sport & Recreation: Ngconde Balfour 24. Trade & Industry: Alec Erwin 25. Transport: Dullah Ornar 26. Water Affairs and Forestry: Ronnie Kasrils 27. Welfare & Population Development: Zola Skweyiya 28. Intelligence: Joe Nhlanhla 29. Presidency: Essop Pahad Deputy ministers: 1. Agriculture & Land Affairs: Dirk du Toit 2. Arts, Culture, Science & Technology: Bridgitte Mabandla 3. Defence: Nozizwe Madlala-Routledge 4. Education: Smangaliso Mkhatshwa 5. Environmental Affairs & Tourism: Joyce Mabudafhasi 6. Finance: Sipho Mphahlwa 7. Foreign Affairs: Aziz Pahad 8. Horne Affairs: Lindiwe Sisula 9. -

Department of Correctional Services Annual Report 2008/09 1 Management Structure

gfpgf art nerships wit h ext ernal st akeholders, t hrough:gg The int egrat ed applicat i nd direct ion offff all Depart ment al resources t o focus on t he correct ion of ffendingff g behaviour, t he promot ion off social responsibilit y and t he overal evelopment offffffff t he person under correct ion; The cost -effect ive provision of rrect ional ffffacilit ies t hat will promot e efficientff securit y, correct ion, care nd development services wit hin an enablinggg human right s environment; Progressive and et hical management and st aff pract ices wit hin which eve Placinggf rehabilit at ion at t he cent re of all Depart ment al act ivit ies in art nershipsDepartment wit h ext ernal st of akeholders, Correctional t hrough:gg The Services int egrat ed applicat i nd direct ion offff all Depart ment al resources t o focus on t he correct ion of ffendingff g behaviour,Annual t he promotReport ion of ffor social theresponsibilit y and t he overal velopment offffffff t he person under correct ion; The cost -effect ive provision of rrect ional 2008/09ffffacilit ies t hat willFinancial promot e efficientff Year securit y, correct ion, care nd development services wit hin an enablinggg human right s environment; Progressive and et hical management and st aff pract ices wit hin which eve Department of Correctional Services Annual Report 2008/09 1 Management Structure 01 Ms Nosiviwe Mapisa- Nqakula, MP 01 02 03 Minister of Correctional Services 02 Ms Hlengiwe Mkhize, MP Deputy Minister of Correctional Services 03 Ms X Sibeko Commissioner of Correctional Services 04 Ms JA Schreiner CDC Operations and Management Support 04 05 06 05 Mr A Tsetsane CDC Corporate Services 06 Mr T Motseki CDC Corrections 07 Ms S Moodley CDC Development and Care 08 Ms N Mareka Acting Chief Financial Officer 07 08 09 09 Vacant Part of the difficulty facing the CDC Central Services Department was stability at Senior 10 Ms N Jolingana Management level.