A Minimum Unified Immunisation Schedule for Spain: Position of the CAV-AEP

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Social-Ecological Impacts of Agrarian Intensification: the Case of Modern Irrigation in Navarre

ADVERTIMENT. Lʼaccés als continguts dʼaquesta tesi queda condicionat a lʼacceptació de les condicions dʼús establertes per la següent llicència Creative Commons: http://cat.creativecommons.org/?page_id=184 ADVERTENCIA. El acceso a los contenidos de esta tesis queda condicionado a la aceptación de las condiciones de uso establecidas por la siguiente licencia Creative Commons: http://es.creativecommons.org/blog/licencias/ WARNING. The access to the contents of this doctoral thesis it is limited to the acceptance of the use conditions set by the following Creative Commons license: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/?lang=en Ph.D. dissertation Social-ecological impacts of agrarian intensification: The case of modern irrigation in Navarre Amaia Albizua Supervisors: Dr. Unai Pascual Ikerbasque Research Professor. Basque Center for Climate Change (BC3), Building Sede 1, 1st floor Science Park UPV/EHU, Sarriena | 48940 Leioa, Spain Dr. Esteve Corbera Senior Researcher. Institute of Environmental Science and Technology (ICTA), Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Building Z Campus UAB | 08193 Bellaterra (Cerdanyola). Barcelona, Spain A dissertation submitted for the degree of Ph.D. in Environmental Science and Technology 2016 Amaia Albizua 2016 Cover: Painting by Txaro Otxaran, Navarre case study region Nire familiari, ama, aita ta Josebari Ta batez ere, amama Felisaren memorian Preface This dissertation is the product of nearly five years of intense personal and professional development. The exploration began when a series of coincidences led me to the Basque Centre for Climate Change Centre (BC3). I had considered doing a PhD since the beginning of my professional career, but the long duration of a PhD and focusing on a particular topic discouraged such intentions. -

Country Report 2013

WAVE LIST 2013 NAtional Women’s Helplines in tHE 28 EU MEMBER STATES The following is a table of the national women’s helplines available in the 28 EU member states. If there is no national helpline, a regional or general helpline is listed (these countries are marked with a *). Country Name Phone number Austria Women’s Helpline against Male Violence +43 800 222 555 Belgium* Hotline for all types of violence, domestic (any member of the family) sexual violence, honor related violence, and more , child abuse, elder abuse, 1712 (Flemish) Ecoute Violences Conjugales (for marital violence) 0800 30 030 (French) SOS Viol (for sexual violence) 02 534 36 36 (French) Crisis Situation Helpline 106 (Flemish) 107 (French) 108 (German) COUNTRY REPORT 2013 Bulgaria Women’s Helpline +359 2 981 76 86 Croatia* Autonomous Women’s House Zagreb 0800 55 44 Cyprus Center for Emergency Assistance Helpline 1440 REALITY CHECK ON EUROPEAN SERVICES Czech Republic* DONA Line +420 251 51 13 13 FOR WOMEN AND CHILDREN SURVIVORS OF VIOLENCE ROSA SOS helpline for women victims of DV +420 602 246 102 +420 241 432 466 Denmark LOKK Hotline +45 70 20 30 82 A Right for Protection and Support? Estonia Estonian Women’s Shelters Union 1492 Finland Women’s Line +358 800 02400 France Viols Femmes Information 0800 05 95 95 Domestic Violence Information 3919 Germany National Women’s Helpline 08000 116 016 Greece National Center for Social Solidarity (E.K.K.A.) 197 Women’s Helpline 15 900 Hungary NaNE Women’s Rights Association 06 80 505 101 +36 4 06 30 006 Ireland National Freephone -

Clivarexchanges

No. 73 September, 2017 CLIVAR Exchanges Special Issue on climate over the Iberian Peninsula: an overview of CLIVAR-Spain coordinated science NASA image courtesy Jeff Schmaltz, LANCE/EOSDIS MODIS Rapid Response Team at NASA GSFC (Source: NASA’s Earth Observatory) CLIVAR Ocean and Climate: Variability, Predictability and Change is the World Climate Research Programme’s core project on the Ocean-Atmosphere System Progress in Detection and Projection of Climate Change in Spain since the 2010 CLIVAR-Spain regional climate change assessment report Enrique Sánchez1, Belén Rodríguez-Fonseca2, Ileana Bladé3, Manola Brunet4, Roland Aznar5, Isabel Cacho6, María Jesús Casado7, Luis Gimeno8, Jose Manuel Gutiérrez9, Gabriel Jordá10, Alicia Lavín11, Jose Antonio López7, Jordi Salat12, Blas Valero13 1 Faculty of Environmental Sciences and Biochemistry, University of Castilla-La Mancha (UCLM), Toledo, Spain 2 Dept. Of Geophysics and Meteorology, Geosciences Institute UCM-CSIC, University Complutense of Madrid, Spain 3 Dept. Applied Physics, Faculty of Physics, University of Barcelona (UB), Barcelona, Spain 4 Centre for Climate Change, Department of Geography, University Rovira i Virgili (URV), Tarragona, Spain 5 Puertos del Estado, Madrid, Spain 6 GRC Geociències Marines, Dept Earth and Ocean Dynamics, University of Barcelona (UB), Barcelona, Spain 7 Agencia Estatal de Meteorología (AEMET), Spain 8 Environmental Physics Laboratory, University of Vigo (UVIGO), Vigo, Spain 9 Meteorology Group. Instituto de Física de Cantabria (CSIC-UC), Santander, Spain 10 IMEDEA, University of Balearic Islands (UIB), Palma de Mallorca, Spain 11 Instituto Español de Oceanografía (IEO), Centro Oceanográfico Santander, Spain 12 Institute of Marine Sciences, CSIC, Barcelona, Spain 13 Pyrenean Institute of Ecology (IPE-CSIC), Zaragoza, Spain Introduction The Iberian Peninsula region offers a challenging prolonged dry periods, heatwaves, heavy convective benchmark for climate variability studies for several reasons. -

Authoritarian Censorship of the Media in Spain Under Franco's Dictatorship Darby Hennessey University of Mississippi

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) 2017 Oprimido, Censurado, Controlado: Authoritarian Censorship of the Media in Spain under Franco's Dictatorship Darby Hennessey University of Mississippi. Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Part of the Journalism Studies Commons Recommended Citation Hennessey, Darby, "Oprimido, Censurado, Controlado: Authoritarian Censorship of the Media in Spain under Franco's Dictatorship" (2017). Honors Theses. 249. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/249 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. OPRIMIDO, CENSURADO, CONTROLADO: AUTHORITARIAN CENSORSHIP OF THE MEDIA IN SPAIN UNDER FRANCO’S DICTATORSHIP By Darby Hennessey A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Mississippi in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College. University, Mississippi © May 2017 Approved by _________________________________________ Advisor: Dr. Samir Husni _________________________________________ Reader: Dr. Robert Magee _________________________________________ Reader: Professor Joe Atkins ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to begin by thanking Dr. Samir Husni, my advisor and professor, who was patient and understanding during the thesis process. I am very grateful for his help, support, and willingness to allow me to handle his magazine collection, partially for thesis purposes, partially because of my own curiosity. Additionally, I would like to thank Dr. Robert Magee and Professor Joe Atkins for their generous willingness to be my additional readers. -

Aki Zaragoza Revista 148. Invierno 2014

sumario DIRECCIÓN 004 AKIDEMODE François Crone 004 Jaguar estrena colección Pilar Alquézar 006 Woolmark Prize 008 Natalia de Lara REDACCIÓN 010 Oro parece Lorena Jarrós 012 Looks para tus pies Maikel Tapia 014 Menuda Feria Jesús Zamora 016 Tendencia: relojes 020 Pirelli 2015 Jaime Machín 022 Nupzial 2014 Cristina Martínez 032 Belleza 038 Entrena con Alex Lamata FOTOGRAFÍA 042 Ideas para regalar Agencia Almozara 046 News Fran Blanco Joaquín Arpa 048 AKICULTURAL Belén Andrés 048 Entrevista: Manuel Cabello 050 Cine y Delicatessen musical MAQUETACIÓN 052 Entrevista: Carmen París Aki Zaragoza 056 Entrevista: Alasdair Fraser Sandra López Cartie 058 Entrevista: Crisalida 060 Libros EDITA Y PUBLICA ICA S.L. Cádiz, 3, 4º dcha. 061 AKIJACETANIA 062 Bienvenidos al frío polar 50.004 Zaragoza 066 Mima tu cuerpo Tel: 976 36 70 14 068 Gastronomia Jacetana Mv: 678 53 21 87 070 La Jacetania [email protected] 080 Entrevista a Marco Lobera 082 Avistamiento de aves Esta publicación no se res- ponsabiliza de las opiniones 092 AKISPORT y trabajos realizados por sus colaboradores y redactores. 096 AKISOCIETY 096 News Quedan reservados todos los derechos. 109 AKIGASTRONOMIA AKI MODA Pilar Alquézar JAGUAR ESTRENA SU COLECCIÓN HERITAGE ´57 Los diseñadores de Jaguar han realizado un amplio catálogo de prendas para conme - morar el periodo más exitoso de la marca británica en las 24 Horas de Le Mans, emple - ando el mítico Jaguar D-Type con dorsal #3 del equipo `Curie Ecosse´ como ele - mento principal de diseño de la colección Heritage ´57 Men´s Brown LeatHer Jacket_ Esta clásica cazadora de cuero está confeccionada en el Reino Unido por Pittards, un especialista mundialmente reconocido en el manejo de la piel de primera calidad. -

Non-Iberian Spanish Nationalism Examined

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) Spring 4-30-2020 Nationalism Beyond a Nation: Non-Iberian Spanish Nationalism Examined George Ruggiero IV Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Part of the Economics Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, Other Political Science Commons, and the Politics and Social Change Commons Recommended Citation Ruggiero IV, George, "Nationalism Beyond a Nation: Non-Iberian Spanish Nationalism Examined" (2020). Honors Theses. 1578. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/1578 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nationalism Beyond a Nation: Non-Spanish Iberian Nationalism Examined ©2020 By George Ruggiero IV A thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for completion Of the Bachelor of Arts degree in International Studies Croft Institute for International Studies Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College The University of Mississippi University, Mississippi May 2020 Approved: Advisor: Dr. Miguel Centellas Reader: Dr. Douglass Sullivan-Gonzalez Reader: Dr. Oliver Dinius 1 Table of Contents Abstract 3 Introduction 3 Research Question and Rationale 4 Theoretical Framework 5 Research Design 6 1. Case Selection 6 2. Data 9 3. Method 10 Literature Review 11 Historical Review 11 1. Basque Country 11 2. Navarre 14 3. Catalonia 16 4. Galicia 19 Theoretical Framework 22 Data and Analysis 29 Conclusions 37 Bibliography 39 2 Abstract In this thesis, I explore differences between certain non-Spanish nationalist movements within Spain. -

Visual Propaganda As a Political Tool in the Spanish Civil War

Fighting for Spain through the Media: Visual Propaganda as a Political Tool in the Spanish Civil War Author: Jennifer Roe Hardin Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/3078 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2013 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. © Jennifer Roe Hardin 2013 Abstract The Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) possesses an historical identity distinct from other national conflicts because of its chronological position between World War I and World War II. International ideological interests came to the forefront of the Spanish conflict and foreign powers became involved in the Republican and Nationalist political factions with the hopes of furthering their respective agendas. The Spanish Civil War extended the aftermath of World War I, as well as provided a staging ground for World War II. Therefore, the Spanish Civil War transformed into a ‘proxy war’ in which foreign powers utilized the national conflict to further their ideological interests. In order to unite these diverse international socio-political campaigns, governments and rebel groups turned to modern visual propaganda to rally the public masses and move them to actively support one side over the other. Propaganda film and poster art supplied those involved in the Spanish Civil War with an invaluable political tool to issue a call to action and unite various political factions around one ideological movement. Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank Professor John Michalczyk for his unwavering guidance and support throughout the entire thesis process. -

The Institution of Linguistic Dissidence in the Balearic Islands: Ideological Dynamics of Catalan Standardisation

PhD-FLSHASE-2018-07 Escola de Doctorat The Faculty of Language and Literature, Humanities, Arts and Education DISSERTATION Defence held on 19/02/2018 in Luxembourg to obtain the degree of DOCTEUR DE L’UNIVERSITÉ DU LUXEMBOURG EN SCIENCES DU LANGAGE AND DOCTOR EN SOCIETAT DE LA INFORMACIÓ I EL CONEIXEMENT PER LA UNIVERSITAT OBERTA DE CATALUNYA by Lucas John DUANE BERNEDO Born on 15 November 1984 in New York (USA) THE INSTITUTION OF LINGUISTIC DISSIDENCE IN THE BALEARIC ISLANDS: IDEOLOGICAL DYNAMICS OF CATALAN STANDARDISATION Dissertation defence committee Dr Julia de Bres, dissertation supervisor Associate Professor, Université du Luxembourg Dr Joan Pujolar, dissertation co-supervisor Professor, Universitat Oberta de Catalunya Dr Melanie Wagner, Chair Senior Lecturer, Université du Luxembourg Dr Maite Puigdevall, Vice-chair Professor, Universitat Oberta de Catalunya Dr Kasper Juffermans Postdoctoral Researcher, Université du Luxembourg Dr James Costa Professor, Université Sorbonne Nouvelle - Paris 3 Abstract This thesis describes ethnographically the recent institution of linguistic dissidence in the Balearic Islands, understood as the establishment of a belief in the archipelago’s socio-political field that claims ‘Balearic’, and not the current Catalan, must share official status with Castilian as its authentic autochthonous language. Three associations of language activists created in 2013 are responsible for this development. Given the hegemony of the belief that Catalan is the autochthonous language in the Balearic Islands, linguistic dissidents departed from a marginal social position and saw social media as the means for the materialisation, organisation and gradual crystallisation of their linguistic—and political—activism. Thus, this thesis analyses two years of social media activity of the three language activist associations, together with three interviews with activists and the participation in a highly symbolic activist event. -

ICES 2013: Report of the Working Group on Marine Mammal Ecology (WGMME)

20th ASCOBANS Advisory Committee Meeting AC20/Doc.4.1.b (P) Warsaw, Poland, 27-29 August 2013 Dist. 25 July 2013 Agenda Item 4.1 Review of New Information on Other Matters Relevant for Small Cetacean Conservation Population Size, Distribution, Structure and Causes of Any Changes Document 4.1.b ICES 2013: Report of the Working Group on Marine Mammal Ecology (WGMME) Action Requested Take note Submitted by United Kingdom NOTE: DELEGATES ARE KINDLY REMINDED TO BRING THEIR OWN COPIES OF DOCUMENTS TO THE MEETING ICES WGMME REPORT 2013 ICES ADVISORY COMMITTEE ICES CM 2013/ACOM:26 Report of the Working Group on Marine Mammal Ecology (WGMME) 4–7 February 2013 Paris, France International Council for the Exploration of the Sea Conseil International pour l’Exploration de la Mer H. C. Andersens Boulevard 44–46 DK-1553 Copenhagen V Denmark Telephone (+45) 33 38 67 00 Telefax (+45) 33 93 42 15 www.ices.dk [email protected] Recommended format for purposes of citation: ICES. 2013. Report of the Working Group on Marine Mammal Ecology (WGMME), 4– 7 February 2013, Paris, France. ICES CM 2013/ACOM:26. 117 pp. For permission to reproduce material from this publication, please apply to the Gen- eral Secretary. The document is a report of an Expert Group under the auspices of the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea and does not necessarily represent the views of the Council. © 2013 International Council for the Exploration of the Sea ICES WGMME REPORT 2013 | i Contents Executive summary ................................................................................................................ 5 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 7 2 Adoption of the agenda ............................................................................................... -

Pageants, Popularity Contests and Spanish Identities in 1920S New York Brian D

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst History Department Faculty Publication Series History 2019 Pageants, Popularity Contests and Spanish Identities in 1920s New York Brian D. Bunk University of Massachusetts - Amherst, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/history_faculty_pubs Recommended Citation Bunk, Brian D., "Pageants, Popularity Contests and Spanish Identities in 1920s New York" (2019). Hidden out in the Open: European Spanish Labor Migrants in the Progressive Era. 218. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/history_faculty_pubs/218 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Department Faculty Publication Series by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Published as: “Pageants, Popularity Contests and Spanish Identities in 1920s New York” in Hidden out in the Open: European Spanish Labor Migrants in the Progressive Era Phylis Martinelli and Ana María Varela-Lago, eds. (Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 2019). Chapter 5 Pageants, Popularity Contests, and Spanish Identities in 1920s New York Brian D. Bunk In April 1925 over 1,000 people from all over New York City came to Hunts Point Palace in the Bronx to attend a grand festival hosted by the Galicia Sporting Club. Revelers enjoyed the music of three different bands, competed in dance contests, and perused the 120- page program. One of the evening’s most anticipated events was the crowning of the “Queen of Beauty,” a title that was sure to be “tenaciously contested” by girls and young women of Spanish descent from the United States, Spain, and other countries. -

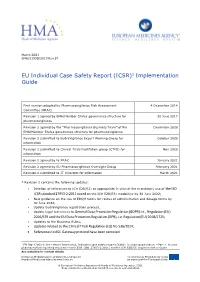

ICSR)1 Implementation Guide

March 2021 EMA/51938/2013 Rev 2* EU Individual Case Safety Report (ICSR)1 Implementation Guide First version adopted by Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment 4 December 2014 Committee (PRAC) Revision 1 agreed by EMA/Member States governance structure for 30 June 2017 pharmacovigilance Revision 2 agreed by the “Pharmacovigilance Business Team” of the December 2020 EMA/Member States governance structure for pharmacovigilance Revision 2 submitted to EudraVigilance Expert Working Group for October 2020 information Revision 2 submitted to Clinical Trials Facilitation group (CTFG) for Nov 2020 information Revision 2 agreed by to PRAC January 2021 Revision 2 agreed by EU Pharmacovigilance Oversight Group February 2021 Revision 2 submitted to IT Directors for information March 2021 * Revision 2 contains the following updates: • Deletion of references to ICH E2B(R2) as appropriate in view of the mandatory use of the ISO ICSR standard 27953-2:2011 based on the ICH E2B(R3) modalities by 30 June 2022; • New guidance on the use of EDQM terms for routes of administration and dosage forms by 30 June 2022; • Update EudraVigilance registration process; • Update legal references to General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) i.e., Regulation (EU) 2016/679 and the EU Data Protection Regulation (DPR), i.e. Regulation (EU) 2018/1725; • Updates to the Business Rules; • Updates related to the Clinical Trials Regulation (EU) No 536/2014; • References to AS1 Gateway protocol have been removed. 1 EN ISO 27953-2:2011 Health Informatics, Individual case safety reports (ICSRs) in pharmacovigilance — Part 2: Human pharmaceutical reporting requirements for ICSR (ISO 27953-2:2011) and the ICH E2B(R3) Implementation Guide See websites for contact details European Medicines Agency www.ema.europa.eu The European Medicines Agency is Heads of Medicines Agencies www.hma.eu an agency of the European Union © European Medicines Agency and Heads of Medicines Agencies, 2021. -

History Writing and Imperial Identity in Early Modern Spain

The Shaping of Empire: History Writing and Imperial Identity in Early Modern Spain By Michael Andrew Gonzales A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Thomas Dandelet, Chair Professor William B. Taylor Professor Ignacio Navarrete Fall 2013 Abstract The Shaping of Empire: History Writing and Imperial Identity in Early Modern Spain by Michael Andrew Gonzales Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Thomas Dandelet, Chair Previous studies on politics and history writing in early modern Europe have focused on how early modern monarchs commissioned official royal histories that served to glorify the crown and its achievements. These works discuss the careers of royal historians and their importance at court, and examine how the early modern crown controlled history writing. In the case of Spain, scholars have argued that Spanish monarchs, particularly Philip II, strictly controlled the production of history writing by censoring texts, destroying and seizing manuscripts, and at times restricting history writing to authorized historians. Modern scholars have largely avoided analyzing the historical studies themselves, and have ignored histories written by non-royal historians. My dissertation broadens the discussion by examining a variety of histories written by royal historians and authors from outside of the court, including clerics, bureaucrats, and military officers, motivated to write histories by their concern over Spain’s recent imperial policies and campaigns. Their discussion of important events in Europe, the Mediterranean, and the Americas uncovers the historical significant of empire as a concept, legacy, and burden during the rise and decline of Spain in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.