Sociology of Paris Match Covers, 1949-2005 Alain Chenu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Der Spiegel-Confirmation from the East by Brian Crozier 1993

"Der Spiegel: Confirmation from the East" Counter Culture Contribution by Brian Crozier I WELCOME Sir James Goldsmith's offer of hospitality in the pages of COUNTER CULTURE to bring fresh news on a struggle in which we were both involved. On the attacking side was Herr Rudolf Augstein, publisher of the German news magazine, Der Spiegel; on the defending side was Jimmy. My own involvement was twofold: I provided him with the explosive information that drew fire from Augstein, and I co-ordinated a truly massive international research campaign that caused Augstein, nearly four years later, to call off his libel suit against Jimmy.1 History moves fast these days. The collapse of communism in the ex-Soviet Union and eastern Europe has loosened tongues and opened archives. The struggle I mentioned took place between January 1981 and October 1984. The past two years have brought revelations and confessions that further vindicate the line we took a decade ago. What did Jimmy Goldsmith say, in 1981, that roused Augstein to take legal action? The Media Committee of the House of Commons had invited Sir James to deliver an address on 'Subversion in the Media'. Having read a reference to the 'Spiegel affair' of 1962 in an interview with the late Franz Josef Strauss in his own news magazine of that period, NOW!, he wanted to know more. I was the interviewer. Today's readers, even in Germany, may not automatically react to the sight or sound of the' Spiegel affair', but in its day, this was a major political scandal, which seriously damaged the political career of Franz Josef Strauss, the then West German Defence Minister. -

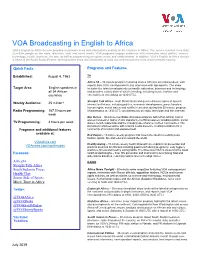

VOA E2A Fact Sheet

VOA Broadcasting in English to Africa VOA’s English to Africa Service provides multimedia news and information covering all 54 countries in Africa. The service reaches more than 25 million people on the radio, television, web, and social media. VOA programs engage audiences with information about politics, science, technology, health, business, the arts, as well as programming on sports, music and entertainment. In addition, VOA’s English to Africa service is home to the South Sudan Project, which provides news and information to radio and web consumers in the world’s newest country. Quick Facts Programs and Features Established: August 4, 1963 TV Africa 54 – 30-minute program featuring stories Africans are talking about, with reports from VOA correspondents and interviews with top experts. The show Target Area: English speakers in includes the latest developments on health, education, business and technology, all 54 African and provides a daily dose of what’s trending, including music, fashion and countries entertainment (weekdays at 1630 UTC). Straight Talk Africa - Host Shaka Ssali and guests discuss topics of special Weekly Audience: 25 million+ interest to Africans, including politics, economic development, press freedom, human rights, social issues and conflict resolution during this 60-minute program. Radio Programming: 167.5 hours per (Wednesdays at 1830 UTC simultaneously on radio, television and the Internet). week Our Voices – 30-minute roundtable discussion program with a Pan-African cast of women focused on topics of vital importance to African women including politics, social TV Programming: 4 hours per week issues, health, leadership and the changing role of women in their communities. -

BORSALINO » 1970, De Jacques Deray, Avec Alain Delon, Jean-Paul 1 Belmondo

« BORSALINO » 1970, de Jacques Deray, avec Alain Delon, Jean-paul 1 Belmondo. Affiche de Ferracci. 60/90 « LA VACHE ET LE PRISONNIER » 1962, de Henri Verneuil, avec Fernandel 2 Affichette de M.Gourdon. 40/70 « DEMAIN EST UN AUTRE JOUR » 1951, de Leonide Moguy, avec Pier Angeli 3 Affichette de A.Ciriello. 40/70 « L’ARDENTE GITANE» 1956, de Nicholas Ray, avec Cornel Wilde, Jane Russel 4 Affiche de Bertrand -Columbia Films- 80/120 «UNE ESPECE DE GARCE » 1960, de Sidney Lumet, avec Sophia Loren, Tab Hunter. Affiche 5 de Roger Soubie 60/90 « DEUX OU TROIS CHOSES QUE JE SAIS D’ELLE» 1967, de Jean Luc Godard, avec Marina Vlady. Affichette de 6 Ferracci 120/160 «SANS PITIE» 1948, de Alberto Lattuada, avec Carla Del Poggio, John Kitzmille 7 Affiche de A.Ciriello - Lux Films- 80/120 « FERNANDEL » 1947, film de A.Toe Dessin de G.Eric 8 Les Films Roger Richebé 80/120 «LE RETOUR DE MONTE-CRISTO» 1946, de Henry Levin, avec Louis Hayward, Barbara Britton 9 Affiche de H.F. -Columbia Films- 140/180 «BOAT PEOPLE » (Passeport pour l’Enfer) 1982, de Ann Hui 10 Affichette de Roland Topor 60/90 «UN HOMME ET UNE FEMME» 1966, de Claude Lelouch, avec Anouk Aimée, Jean-Louis Trintignant 11 Affichette les Films13 80/120 «LE BOSSU DE ROME » 1960, de Carlo Lizzani, avec Gérard Blain, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Anna Maria Ferrero 12 Affiche de Grinsson 60/90 «LES CHEVALIERS TEUTONIQUES » 1961, de Alexandre Ford 13 Affiche de Jean Mascii -Athos Films- 40/70 «A TOUT CASSER» 1968, de John Berry, avec Eddie Constantine, Johnny Halliday, 14 Catherine Allegret. -

TV NATIONAL HONOREES 60 Minutes: the Chibok Girls (60

TV NATIONAL HONOREES 60 Minutes: The Chibok Girls (60 Minutes) Clarissa Ward (CNN International) CBS News CNN International News Magazine Reporter/Correspondent Abby McEnany (Work in Progress) Danai Gurira (The Walking Dead) SHOWTIME AMC Actress in a Breakthrough Role Actress in a Leading Role - Drama Alex Duda (The Kelly Clarkson Show) Fiona Shaw (Killing Eve) NBCUniversal BBC AMERICA Showrunner – Talk Show Actress in a Supporting Role - Drama Am I Next? Trans and Targeted Francesca Gregorini (Killing Eve) ABC NEWS Nightline BBC AMERICA Hard News Feature Director - Scripted Angela Kang (The Walking Dead) Gender Discrimination in the FBI AMC NBC News Investigative Unit Showrunner- Scripted Interview Feature Better Things Grey's Anatomy FX Networks ABC Studios Comedy Drama- Grand Award BookTube Izzie Pick Ibarra (THE MASKED SINGER) YouTube Originals FOX Broadcasting Company Non-Fiction Entertainment Showrunner - Unscripted Caroline Waterlow (Qualified) Michelle Williams (Fosse/Verdon) ESPN Films FX Networks Producer- Documentary /Unscripted / Non- Actress in a Leading Role - Made for TV Movie Fiction or Limited Series Catherine Reitman (Workin' Moms) Mission Unstoppable Wolf + Rabbit Entertainment (CBC/Netflix) Produced by Litton Entertainment Actress in a Leading Role - Comedy or Musical Family Series Catherine Reitman (Workin' Moms) MSNBC 2019 Democratic Debate (Atlanta) Wolf + Rabbit Entertainment (CBC/Netflix) MSNBC Director - Comedy Special or Variety - Breakthrough Naomi Watts (The Loudest Voice) Sharyn Alfonsi (60 Minutes) SHOWTIME -

MEDIA POLARIZATION “À LA FRANÇAISE”? Comparing the French and American Ecosystems

institut montaigne MEDIA POLARIZATION “À LA FRANÇAISE”? Comparing the French and American Ecosystems REPORT MAY 2019 MEDIA POLARIZATION “À LA FRANÇAISE” MEDIA POLARIZATION There is no desire more natural than the desire for knowledge MEDIA POLARIZATION “À LA FRANÇAISE”? Comparing the French and American Ecosystems MAY 2019 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY In France, representative democracy is experiencing a growing mistrust that also affects the media. The latter are facing major simultaneous challenges: • a disruption of their business model in the digital age; • a dependence on social networks and search engines to gain visibility; • increased competition due to the convergence of content on digital media (competition between text, video and audio on the Internet); • increased competition due to the emergence of actors exercising their influence independently from the media (politicians, bloggers, comedians, etc.). In the United States, these developments have contributed to the polarization of the public square, characterized by the radicalization of the conservative press, with significant impact on electoral processes. Institut Montaigne investigated whether a similar phenomenon was at work in France. To this end, it led an in-depth study in partnership with the Sciences Po Médialab, the Sciences Po School of Journalism as well as the MIT Center for Civic Media. It also benefited from data collected and analyzed by the Pew Research Center*, in their report “News Media Attitudes in France”. Going beyond “fake news” 1 The changes affecting the media space are often reduced to the study of their most visible symp- toms. For instance, the concept of “fake news”, which has been amply commented on, falls short of encompassing the complexity of the transformations at work. -

Bibliographie (1) Air Et Cosmos/N°2563/ 29 Septembre 2017 (2) Les

Bibliographie (1) Air et Cosmos/N°2563/ 29 Septembre 2017 (2) Les cahiers de l’Express/N°22/ La conquête de l’espace/Juillet 1993 (3) Les satellites artificiels / Que sais-je ? N°813 / PUF / 1965 (4) Paris-Match / N° 445/ 19 Octobre 1957 (5) Les dossiers du futur/Olivier Orban/Daniel Garric/Décembre 1980 (6) Le Figaro.fr/histoire/archives/02 Novembre 2017 (7) Le livre de l’espace / Denoel / 1978 // (7-1) Le Point/ Hors-Série/ Les chefs d’œuvre de la science-fiction/Novembre-Décembre 2018 (8) La lune et les planètes / Pierre de Latil / 1969 / Collection « Les beaux livres » Hachette (9) Dernières nouvelles du cosmos/ Hubert Reeves/Editions Points/02-2011 (10) Les merveilles du ciel / Guido Ruggieri / 1968 / Collection « Les beaux livres » Hachette (11) Sciences et avenir/N° 850/Décembre 2017 (11-1) Lefigaro.fr/ sciences/ 2018-12-27/01008- 20181227ARTIFIG-decouverte de la plus lointaine planète // (11-2) Sciences et Avenir / N° 864 / Février 2019 (12) Univers / Explorer le monde astronomique/ Phaidon/ Novembre 2017 (13) L’espace pour l’homme / Dominos Flammarion /1993 (14) Le point /N°2348 / 7 Septembre 2017 (15) Sciences et avenir / (16) Sciences et Avenir / N° 858 / Aout 2018 // (16-1) Sciences et Avenir / N° 863 / Janvier 2019 (17) Lefigaro.fr/15-05-2018 (18) Sciences et avenir/N° 846/Aout 2017 (19) Air et Cosmos /N° 835/Septembre 2016 (20) Lefigaro.fr/2018-06-28 (21) Begeek / 25-03-2018 (22) Sciences et Avenir / N° 859 / Septembre 2018 // (22-1) : Le Point/N°2405/4 Octobre 2018// (22- 2) : Air & Cosmos/N° 2620/ 7 Décembre 2018 (23) La -

SERBIA Jovanka Matić and Dubravka Valić Nedeljković

SERBIA Jovanka Matić and Dubravka Valić Nedeljković porocilo.indb 327 20.5.2014 9:04:47 INTRODUCTION Serbia’s transition to democratic governance started in 2000. Reconstruction of the media system – aimed at developing free, independent and pluralistic media – was an important part of reform processes. After 13 years of democratisation eff orts, no one can argue that a new media system has not been put in place. Th e system is pluralistic; the media are predominantly in private ownership; the legal framework includes European democratic standards; broadcasting is regulated by bodies separated from executive state power; public service broadcasters have evolved from the former state-run radio and tel- evision company which acted as a pillar of the fallen autocratic regime. However, there is no public consensus that the changes have produced more positive than negative results. Th e media sector is liberalized but this has not brought a better-in- formed public. Media freedom has been expanded but it has endangered the concept of socially responsible journalism. Among about 1200 media outlets many have neither po- litical nor economic independence. Th e only industrial segments on the rise are the enter- tainment press and cable channels featuring reality shows and entertainment. Th e level of professionalism and reputation of journalists have been drastically reduced. Th e current media system suff ers from many weaknesses. Media legislation is incom- plete, inconsistent and outdated. Privatisation of state-owned media, stipulated as mandato- ry 10 years ago, is uncompleted. Th e media market is very poorly regulated resulting in dras- tically unequal conditions for state-owned and private media. -

Montants Totaux D'aides Pour Les 200 Titres De Presse Les Plus Aidés En

Tableau des montants totaux d’aides pour les 200 titres de presse les plus aidés Les chiffres annuels d’aides à la presse doivent être lus avec quelques précautions. En particulier, la compensation du tarif postal, première aide publique de soutien au secteur de la presse, est versée à La Poste pour compenser les coûts de la mission de service public de transport postal de la presse (validée par les autorités européennes), coûts évalués par l'opérateur. Enfin, à ce jour, l'aide à l’exemplaire n'est calculée que pour les titres dont la diffusion est communiquée à l’OJD; certains chiffres de diffusion sont d’ailleurs susceptibles d’évoluer à la marge. Une notice, jointe au tableau, explique la façon dont celui-ci a été réalisé et comment il se lit. Dont aides Dont Dont aides directes – hors Dont aide à la Diffusion/An Aides par Aides à la Total des Aides à la Ordre Titre Compensation versées aux aide à la Distribution 2013 en exemplaire en production en Aides en € diffusion en € Tarif postal en € tiers en € distribution – en € exemplaires € € en € 1 LE FIGARO 16 179 637 7 378 383 1 078 951 2 136 790 5 585 513 101 056 679 0,160 14 527 134 1 652 503 2 LE MONDE 16 150 256 4 811 140 3 839 762 2 307 359 5 191 995 92 546 730 0,175 13 654 790 2 495 466 3 AUJOURD'HUI EN FRANCE AUJOURD'HUI EN FRANCE DIMANCHE 11 997 569 427 027 242 890 201 069 11 126 583 57 358 270 0,209 11 754 679 242 890 4 OUEST FRANCE - DIMANCHE OUEST FRANCE 10 443 192 2 479 411 536 881 7 426 900 0 251 939 246 0,041 7 700 818 2 742 374 5 LA CROIX 10 435 028 5 101 574 0 5 053 079 -

The Beauty of the Real: What Hollywood Can

The Beauty of the Real The Beauty of the Real What Hollywood Can Learn from Contemporary French Actresses Mick LaSalle s ta n f or d ge n e r a l b o o k s An Imprint of Stanford University Press Stanford, California Stanford University Press Stanford, California © 2012 by Mick LaSalle. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system without the prior written permission of Stanford University Press. Printed in the United States of America on acid-free, archival-quality paper Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data LaSalle, Mick, author. The beauty of the real : what Hollywood can learn from contemporary French actresses / Mick LaSalle. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8047-6854-2 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Motion picture actors and actresses--France. 2. Actresses--France. 3. Women in motion pictures. 4. Motion pictures, French--United States. I. Title. PN1998.2.L376 2012 791.43'65220944--dc23 2011049156 Designed by Bruce Lundquist Typeset at Stanford University Press in 10.5/15 Bell MT For my mother, for Joanne, for Amy and for Leba Hertz. Great women. Contents Introduction: Two Myths 1 1 Teen Rebellion 11 2 The Young Woman Alone: Isabelle Huppert, Isabelle Adjani, and Nathalie Baye 23 3 Juliette Binoche, Emmanuelle Béart, and the Temptations of Vanity 37 4 The Shame of Valeria Bruni Tedeschi 49 5 Sandrine Kiberlain 61 6 Sandrine -

A Fascinating Literary Puzzle Very Special Souvenirs!

http://enter.lagardere.net www.lagardere.com INNOVATION IS CORE TO OUR BRANDS AND BUSINESSES A fascinating literary puzzle 02 Calmann-Lévy publishes Guillaume Musso’s new novel Very special souvenirs! 03 Lagardère Travel Retail France reappointed to run Eiffel Tower offi cial stores May 2019 #150 PUBLISHING More Stories from Gaul Asterix celebrates his 60th birthday this year, and to mark the occasion, Éditions Albert René are reissuing the very fi rst Asterix book – Astérix le Gaulois – in both luxury and Artbook editions. This anniversary year will culminate in the publication, on October 24, of the 38th book in the Asterix series, with a projected print run of more than 5 mil- © Emanuele Scorcelletti lion copies: La Fille de Vercingétorix. Calmann-Lévy publishes Guillaume Musso’s new novel Late February brought the debut of a new Instagram account, #lArtdAsterix, that offers an inside look at “the art of Asterix”. www.asterix.com A fascinating literary puzzle Guillaume Musso at Hachette Livre island, determined to discover his lated into 34 languages. In July it TRAVEL RETAIL is hitting the headlines twice with secret. That same day, a woman’s will be released as The Reunion the release of La Vie secrète des body is found on a beach and the by Little, Brown in the United States écrivains (Authors’ secret life) and island is cordoned off by the author- and Orion in the UK, and produc- the paperback version of La Jeune ities. Thus begins a dangerous con- tion of a TV adaption for France Fille et la Nuit. frontation between Mathilde and Télévisions is set to start soon. -

Les Cultes Religieux Face À L'épidémie De Covid-19 En France

RÉPUBLIQUE FRANÇAISE OFFICE PARLEMENTAIRE D’ÉVALUATION DES CHOIX SCIENTIFIQUES ET TECHNOLOGIQUES Note à l’attention des membres de l’Office Les cultes religieux face à l’épidémie de Covid-19 en France Cette note a été présentée en réunion de l’Office parlementaire d’évaluation des choix scientifiques et technologiques le 2 juillet 2020, conjointement avec une note relative aux rites funéraires, par Pierre Ouzoulias, sénateur, et validée pour publication. Sous la présidence de Gérard Longuet et la vice-présidence de Cédric Villani, l’Office parlementaire d’évaluation des choix scientifiques et technologiques (OPECST) a souhaité s’intéresser davantage aux rapports entre les sciences et la société, comme en témoigne l’introduction de notes scientifiques, supports pédagogiques d’information sur les questions d’actualité. Pendant toute la durée de la crise sanitaire, s’acquittant autant qu’il était possible de sa mission d’information du Parlement, il a procédé à de nombreuses auditions et publié plusieurs notes, dans des champs disciplinaires multiples, afin de tenter un bilan le plus complet possible des enjeux politiques et scientifiques de la gestion de la pandémie provoquée par l’irruption du coronavirus. La grande diversité des questions abordées, de l’impact de l’épidémie sur les enfants aux enjeux du port du masque ou à l’utilité des technologies de l’information, témoigne de cette volonté d’appréhender l’épidémie, ses causes, sa gestion et ses conséquences, dans toutes ses dimensions médicales, scientifiques et sociales. Il est donc apparu évident aux membres de l’OPECST et à ses présidents, de façon un peu inédite, d’élargir les sujets d’intérêt habituels de l’Office à des questions plus sociales. -

Reference Document Including the Annual Financial Report

REFERENCE DOCUMENT INCLUDING THE ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT 2012 PROFILE LAGARDÈRE, A WORLD-CLASS PURE-PLAY MEDIA GROUP LED BY ARNAUD LAGARDÈRE, OPERATES IN AROUND 30 COUNTRIES AND IS STRUCTURED AROUND FOUR DISTINCT, COMPLEMENTARY DIVISIONS: • Lagardère Publishing: Book and e-Publishing; • Lagardère Active: Press, Audiovisual (Radio, Television, Audiovisual Production), Digital and Advertising Sales Brokerage; • Lagardère Services: Travel Retail and Distribution; • Lagardère Unlimited: Sport Industry and Entertainment. EXE LOGO L'Identité / Le Logo Les cotes indiquées sont données à titre indicatif et devront être vérifiées par les entrepreneurs. Ceux-ci devront soumettre leurs dessins Echelle: d’éxécution pour approbation avant réalisation. L’étude technique des travaux concernant les éléments porteurs concourant la stabilité ou la solidité du bâtiment et tous autres éléments qui leur sont intégrés ou forment corps avec eux, devra être vérifié par un bureau d’étude qualifié. Agence d'architecture intérieure LAGARDERE - Concept C5 - O’CLOCK Optimisation Les entrepreneurs devront s’engager à executer les travaux selon les règles de l’art et dans le respect des règlementations en vigueur. Ce 15, rue Colbert 78000 Versailles Date : 13 01 2010 dessin est la propriété de : VERSIONS - 15, rue Colbert - 78000 Versailles. Ne peut être reproduit sans autorisation. tél : 01 30 97 03 03 fax : 01 30 97 03 00 e.mail : [email protected] PANTONE 382C PANTONE PANTONE 382C PANTONE Informer, Rassurer, Partager PROCESS BLACK C PROCESS BLACK C Les cotes indiquées sont données à titre indicatif et devront être vérifiées par les entrepreneurs. Ceux-ci devront soumettre leurs dessins d’éxécution pour approbation avant réalisation. L’étude technique des travaux concernant les éléments porteurs concourant la stabilité ou la Echelle: Agence d'architecture intérieure solidité du bâtiment et tous autres éléments qui leur sont intégrés ou forment corps avec eux, devra être vérifié par un bureau d’étude qualifié.